Introduction

In recent years, “late antique epigraphy” has increasingly become a field of study of its own, and it now appears as a phenomenon sui generis – as demonstrated by conference volumes like La terza età dell’epigrafia (1988), or The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity (2017).1 The current situation of the field implies that we should think about and define the chronological limits of this phenomenon – something that is rather rarely done.2 The starting point in the later 3rd century AD seems quite clear, but we also have to raise the question when “late antique epigraphy” came to an end. It is this problem which will be discussed in the following essay that does not pretend to give any clear-cut answers.3

Some basic questions of definition

Let us start with some basic questions of definition: the first one, what is an “inscription”?; the second, what are the main characteristics of the ancient “epigraphic habit”?; and the third, which features are typical for “late antique epigraphy”?

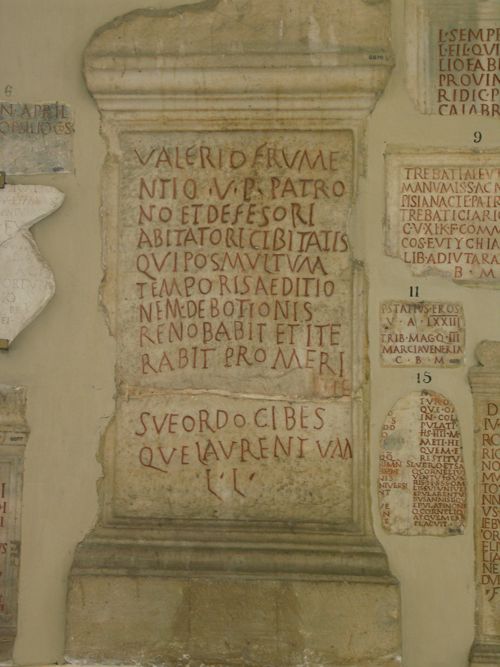

What is an “inscription”? This apparently easy question – raised from the perspective of an ancient historian – is in fact quite difficult to answer; in my opinion, no wholly convincing explanation has yet been put forward.4 I will therefore try to present a sort of “working definition” which consists of the following points. It is important to note at the outset that not every scripted artefact produced in Antiquity can count as an “inscription”, but only a special group of inscribed monuments. This group consists of textual messages that were carved into a durable material (in most cases stone or bronze) following a conscious decision by an individual or a group (◉1). An epigraphic message of this kind was intended to last for a longer period, i.e. it was meant to serve for more than an ephemeral purpose.5 An “inscription” thus had a twofold function of both communication and commemoration. It informed contemporary observers about certain facts (for example the laudable behaviour of a given person) and at the same time preserved the memory of these persons and their deeds for posterity. This is in turn meant that inscriptions needed an audience – be it public, large or potentially indefinite; or rather private, restricted or even reduced to a very few persons at a specific moment like a funeral.6 Sometimes it was enough to know (or to remark from a distance) that an inscribed text was present at a certain place although it could not be read in detail by most people. The legibility or readability of an inscribed text was thus not always its primary function (something many epigraphists do not like to hear but which seems obvious when looking at the placement and layout of many ancient inscriptions); instead, the monumental quality of ancient inscriptions was very important, also for the rather high number of illiterates – an inscribed text could impress people by its very presence, its layout and its specific materiality.7 This statement is further underlined by another observation: Ancient inscriptions were nearly never “acting” alone (indeed, the word “inscription” which implies a category of its own is rather misleading in certain respects), but as part of a larger monumental or spatial context; and they were also often interacting with other media of communication, for example visual ones (statues etc.).8

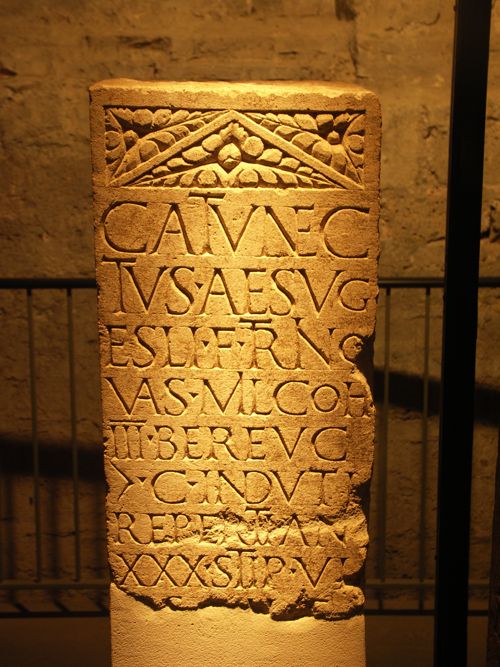

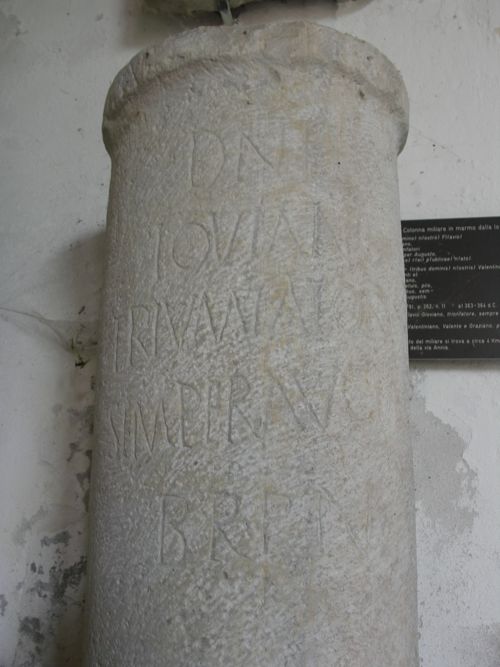

What are the main characteristics of the “epigraphic habit” of Antiquity? The epigraphic landscapes of Antiquity were manifold and complex; to make things not too complicated, the following discussion will concentrate on the Roman Empire; and within the Imperium Romanum mainly on its western parts (Italy, Gaul, Spain, and Africa), with some digressions to the East. It will further focus on urban contexts where most inscriptions were to be found. Another important place for Roman inscriptions, the sphere of the army, is not considered in detail, and this is also true for the rural world. In the Roman Empire the heyday of a quantitatively and qualitatively important “epigraphic habit” was the period from the first c. BC until the mid-third c. AD.9 It was characterized by a mass production of inscriptions of different kinds. In the western parts of the Roman Empire this phenomenon started rather late, i.e. in the course of the later First century BC, followed by a veritable “boom” in the Augustan period (influenced by the actions and the example of the first princeps himself) and reaching its climax in the 2nd and early 3rd c. AD.10 Around 90% of these inscriptions can be categorized within four main groups. The two largest groups in numbers were funerary and votive inscriptions with often rather simple and short texts (◉2, 3). Of special importance for defining the “epigraphic habit” of Antiquity, however, is another phenomenon, i.e. the so-called “civic inscriptions”, consisting of honorific inscriptions on statue bases and building inscriptions attached to constructions that were newly erected or restored (◉4). A special form of the latter were milestones, mostly columnar monuments which were placed along the main roads of the Empire. As stated before, one of the main purposes of these “civic inscriptions” was the commemoration of virtues and deeds that men (and sometimes women) had performed for the well-being of their communities; and these written messages were also very important for enhancing and preserving the social prestige of the municipal and imperial elites within the Empire.

Cat. Inscr. Imper. Aug. Emerita 10; Date: 8/7 BC; © C. Witschel.

To fulfil these tasks, epigraphic monuments had to be presented in the public sphere of ancient cities like the central places (fora) or large buildings which were accessible for everyone.11 An important part of ancient cities consisted of the public sphere which was often much larger than necessary for the rather small resident population in many towns of the Empire. One can thus say that there was a close connection between the production and placement of “civic inscriptions” and the existence of a large public sector within Roman cities in the late Republic and Imperial periods (i.e. from the 1st c. BC to the 3rd c. AD). Inscriptions were therefore an integral part of ancient city life, and the public spaces of the cities were often tightly filled with epigraphic monuments (◉5). The latter were directed towards an intended audience and often “offered” themselves to potential viewers. This becomes clear when we look at the design and the layout of such inscriptions: Precious materials like marble blocks were used as well as deeply carved, regular, and large letters (litterae capitales quadratae), often rendered even more visible by the application of colours and plaster.12 Ancient authors sometimes speak of a special kind of litterae lapidariae which were comprehensible even for semi-literates.13

Another characteristic of the ancient “epigraphic habit” was the rather high homogeneity of epigraphic monuments which were produced en masse in specialized workshops throughout the Mediterranean provinces of the Empire. But already during the high imperial period some regional variations become visible. To mention just one point: the number of “civic inscriptions”, especially inscribed statue bases, was – for reasons that are not easily discernible – much lower in the north-western provinces of the Empire (Northern Gaul, Germania, Britain) than in the Mediterranean core regions of the Imperium Romanum.14

What in contrast is typical for “late antique epigraphy”? It is important to note at the outset that “late antique epigraphy” does not equal “Christian epigraphy” – the former phenomenon began earlier than the large-scale Christianisation of the Roman Empire during the (later) 4th and 5th centuries, and it also had a much broader scope: in Late Antiquity, all different kinds of inscriptions were still present; and many of them appear as religiously “neutral” or “indifferent”, even in contexts which are deemed specifically “Christian” like the catacombs in Rome.15

With regard to the development of the epigraphic habit in Late Antiquity, the most remarkable feature is the massive quantitative reduction of newly produced inscriptions from the mid third century onwards (and in some regions even starting earlier).16 This general tendency can be observed in all regions of the West and in most of the East, but there are also marked regional differences – indeed, divergent developments even in neighbouring regions come much more to the foreground in Late Antiquity than in earlier periods.17 In some regions like Africa late antique inscriptions still represent a considerable share of the overall number of epigraphic documents known from Antiquity, whereas in other regions their number is exceedingly small, as in parts of Gaul. It is not easy to explain these regional variations – as we will see, a low number of late antique inscriptions in a given region is certainly not a direct reflection of its economic or demographic situation as we know of prosperous and densely inhabited landscapes like Lycia in southern Asia minor were nearly no late antique inscriptions have been found at all.18 We might also note that there are exceptions from this general trend in some regions of the East like Northern Syria or Palestine, where the production of inscriptions reached its climax (at least in sheer numbers) only in the 5th or 6th centuries.19

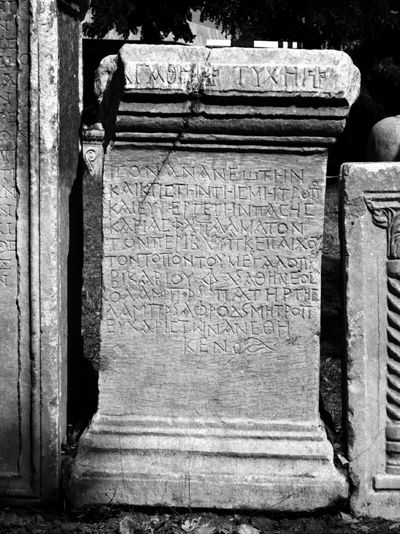

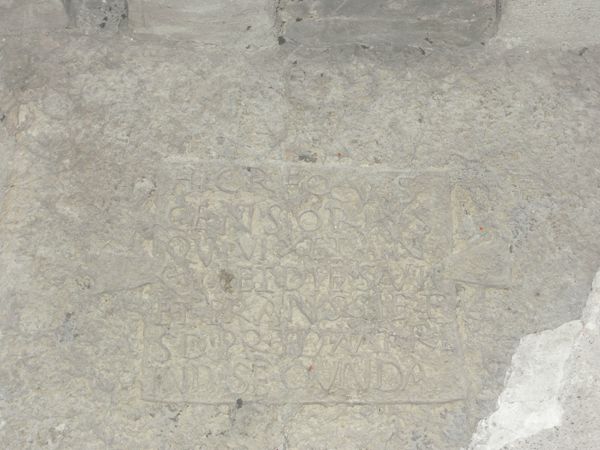

Turning now to qualitative changes, I would like to highlight the following three features: (a) the massive upsurge in the reuse of earlier epigraphic monuments, both as building material and for carving new texts (e.g. on statue bases) (◉6, 7);20 (b) the changing modes of expression as seen in the wording of many late antique inscriptions, especially in honorific texts: instead of the “crisp” and standardized lists of offices and merits in the cursus honorum of high imperial magistrates we now encounter in the West long series of highly rhetorical phrases in order to praise an honorand (what has been called “orations in stone”),21 and in the East metrical epigrams composed in an archaizing, Homeric language which only members of the well-educated elite could fully understand in all their complexity;22 and (c) a loss of homogeneity in the outward appearance of epigraphic monuments: many late antique inscriptions are characterized by smaller and more irregular letters, and the layout often looks “careless” (◉8) – at least to our eyes, trained in looking at “classical” inscriptions; it is, however, not certain whether late antique observers would have had the same impression.23 This phenomenon was not a question of less money available, as even the epigraphic monuments of the richest senators in Rome often show these tendencies (◉9).24 On the other hand, when people specifically wanted to create an inscription that looked like those of older times, they could still do so (◉ ). But the demand for such epigraphic moments seems to have declined considerably, and therefore we can assume that most of the workshops which had specialized in the production of high-quality inscriptions during the imperial period went out of use. Inscriptions were now carved in many ways according to the available technical resources and perhaps also to the divergent taste of customers; and this in turn created a very heterogeneous picture when looking at the late antique epigraphic record.

). But the demand for such epigraphic moments seems to have declined considerably, and therefore we can assume that most of the workshops which had specialized in the production of high-quality inscriptions during the imperial period went out of use. Inscriptions were now carved in many ways according to the available technical resources and perhaps also to the divergent taste of customers; and this in turn created a very heterogeneous picture when looking at the late antique epigraphic record.

as building material. © C. Witschel.

The “epigraphic habit” in the West

from the mid-3rd to the early 5th centuries

The changes described above are most visible in the numerical decline of “civic inscriptions”, but this process was quite unequal in the different regions of the western Empire.25 For example, in Gaul and especially in Aquitaine, the number of “civic inscriptions” declined early and very radically. Because Aquitania was a rich region dominated by a cultivated elite during the 4th and 5th centuries as we know both from literary sources and from the excavations of their sumptuous villas, this development cannot have been the result of economic or cultural decline; rather, we have to suppose that other means of elite communication and self-representation took the place of inscriptions already during the 4th century.26 In Spain, the change was not as radical as in Southern Gaul, but here we can observe a marked concentration of late antique civic inscriptions (mostly from the late 3rd to 4th centuries) in the administrative capitals and large metropoleis of late antique Hispania, whereas the many smaller towns which had dominated the scene in the early imperial period and had mostly survived into Late Antiquity have only very rarely yielded “civic inscriptions” from this period.27 Central North Africa was the most conservative region in this respect: here, a highly traditional urban elite produced a much higher number of “civic inscriptions” (esp. building and restoration inscriptions) during the 4th century than in any other part of the western Empire; and this not only pertained to the large cities like Lepcis Magna (◉10, 11),28 but also to many of the smaller ones. In Italy, we encounter remarkable sub-regional differences between the North (Venetia et Histria), the Centre (Tuscia et Umbria) and the South (Campania, Apulia et Calabria) compared to the survival (or not) of “civic inscriptions” into Late Antiquity: their number is low in the politically and economically dominant regions of the North and much higher in the South of the peninsula where the conservative senatorial class of Rome set the tone.29

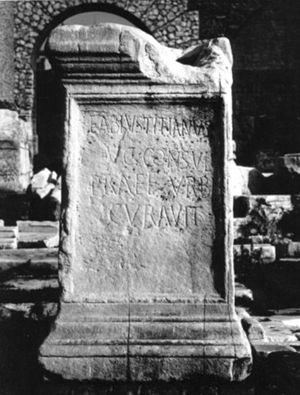

Yet in the North of Italy, we can also see that public spaces like the fora were still used for the presentation of epigraphic monuments during the 4th century.30 In this context two remarkable features should be emphasised. On the one hand, inscribed statuary monuments with an honorific function were no longer erected (even for Emperors) on the fora of cities of Northern Italy from the middle of the 4th c. onwards. On the other hand, the forum of Aquileia can demonstrate that the central places of most towns were kept intact and were used for the display of epigraphic monuments and statues, often older ones which were brought to the forum from other places within the city and rearranged there (◉12, 13). Regarding the epigraphic presence of the Emperor the place of public spaces within the cities was taken over by the large roads leading through the territory of the towns. We can thus observe a sharp increase in the number of milestones erected along the main roads of Northern Italy from the late 3rd c. onwards (◉14).31 Milestones of this period were mainly honorific monuments for the reigning Emperor(s) as can be seen by the use of panegyric formulae in their inscriptions; and some of these columns might have even carried a portrait of the Emperor.

We may therefore conclude that the epigraphic habit of the 4th century was – despite all the changes both in quantity and in quality of the inscriptions – still recognizably “antique” in character.

The “later late cities” of the 5th/6th centuries

in Italy and their epigraphic culture(s)

But what about the following period of the 5th and 6th centuries when the western Roman Empire came to an end and Germanic “successor states” were established in most parts of the West? Let us look again at the case of Italy as the core region of the western Empire with a high amount of administrative and social continuity even after the disposal of the last western Emperor in AD 476. This is especially true for the Ostrogothic period from AD 493 onwards. A decisive break only occurred with the prolonged Byzantine-Gothic wars of the mid-6th c., the Byzantine reconquest of Italy and finally the Lombard invasion of AD 568 – from a structural point of view, “antiquity” only came to an end in Italy during the second half of the 6th c.

But what about the “epigraphic habit” in Italy during this period?32 In this respect, pronounced changes can be noticed starting from the early 5th c. onwards. They are again very marked and characterized by some key aspects, first of all by a sharp decline in the number of honorific monuments in those regions where they had still existed in the earlier phase of Late Antiquity, i.e. statues and their inscriptions for members of the elite and Emperors which were reduced to nearly zero by the middle of the 5th century even in the city of Rome. Other kinds of inscribed monuments naming the Emperor like building inscriptions were also much reduced; from the middle of the 5th century onwards the short-reigning Emperors of the last phase of the western Empire mostly vanish from the epigraphic record. This is also due to the complete disappearance of milestones from around AD 400, although this class of inscriptions had fared so strongly during the 4th century (see above). There was no reversal of these trends during the politically more stable Ostrogothic period: although their king Theoderic was praised as a “restorer of the cities” during his long reign, inscriptions exhibiting his name are quite rare.33

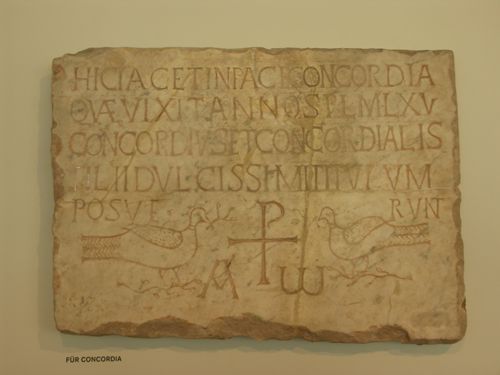

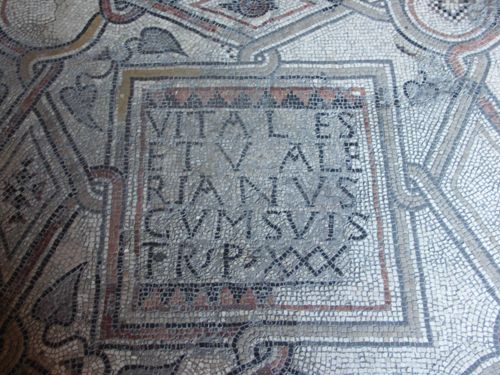

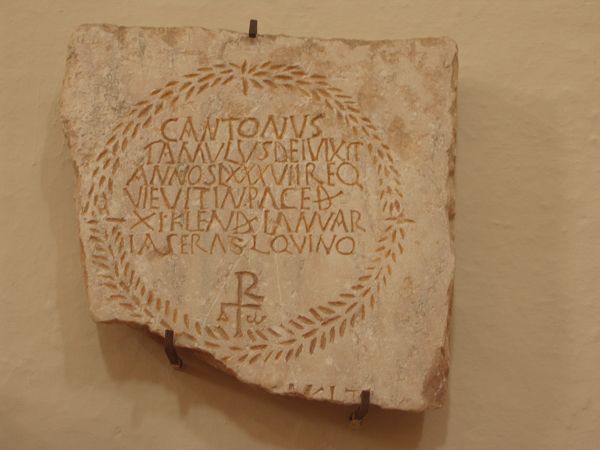

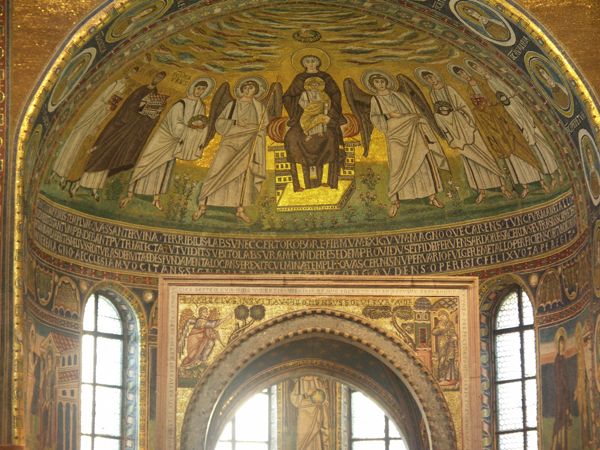

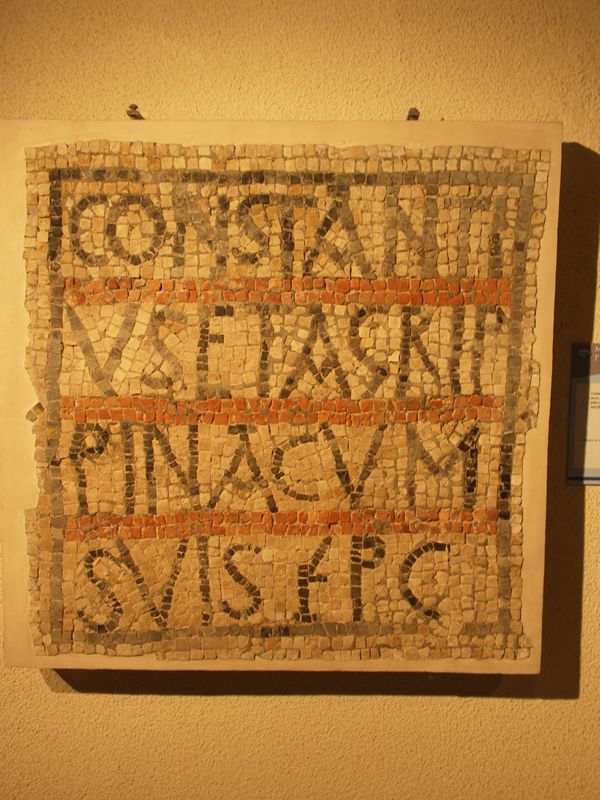

This development led to a concentration of the surviving epigraphic production on two kinds of inscriptions from the early/middle 5th century onwards: on the one hand, building and donor inscriptions in churches, which were mostly placed in the interior of these buildings and not on their outer facades; and on the other hand funerary inscriptions which now often showed explicit Christian symbols and formulae (◉15).34 There also was a remarkable spatial shift from the open public spaces like fora (which were now mostly abandoned or given over to other uses even in those regions where they had remained in use during the 4th century like Italy and Africa) to the interior of ecclesiastical buildings and to the sphere of graves where the epitaphs were often only to be seen by a very restricted number of people.35 These trends have been labelled as an “interiorization” of representation – a remarkable feature in an “open air society” that for many centuries had been dominated by the presence of large public spaces filled with epigraphic monuments.36 In some regions of Italy like in the North East there was also a shift in the materiality of inscriptions present in churches, as we have already seen: instead of messages engraved in stone, texts in mosaics on the floors and walls of churches now became dominant, commemorating the donations of members of the elite, but also of “small people” who had paid for the erection and decoration of these buildings (◉16).37

CIL V 1612 = Inscr. Aquil. III 3358; Date: Around AD 580; © C. Witschel.

Conclusion:

When did “late antique epigraphy” come to an end?

At the beginning of this conclusion, it has once more to be stressed that I am concentrating on the developments of “late antique epigraphy” in the West of the Mediterranean. In contrast, we are confronted with quite different trends in the (Byzantine) East at least as far as the 5th and earlier 6th centuries are concerned. To give just two examples for these divergences: new statuary monuments with honorific texts inscribed on their bases were still put up on the agorai and within public buildings of some cities in Asia minor like Aphrodisias until well into the 6th century (◉17a-b);38 and in other regions like Palestine the number of (mainly Christian) inscriptions even increased in this period39 – we can detect nothing comparable in the West.

Date: Late 5th/early 6th c. AD; © ALA and C. Witschel.

Returning now to the West we can again ask for chronological boundaries: To begin with, it is relatively easy to delimit a first phase of “late antique epigraphy” lasting from the mid-3rd to the early 5th century. Despite the clearly recognizable changes from the previous imperial period that we have discussed above, notably the strong reduction of freshly carved epigraphic monuments and especially of “civic inscriptions”, the epigraphic practices in use during this period were still to a considerable extent situated within the public sphere of the cities and their territories. A prime example is the massive upsurge in the erection of milestones along the main roads in some regions like Northern Italy during the 4th century;40 or the high number of restoration inscriptions pertaining to public buildings even in small towns of Africa.41 Most of these inscriptions presented in public were more or less “neutral” in religious terms, although the Christianisation of the Roman Empire became more pronounced in the course of the 4th century.42 This situation was not the least a result of the decision of church leaders not to try to “conquer” the outdoor public sphere of cities through epigraphic monuments of their own in order to communicate a distinct Christian message. In this context one also must keep in mind that in most regions of the West a real “boom” in the construction of large communal churches which was to transform the urban landscapes to a considerable scale only started in the late 4th century at the earliest. So, for several reasons the epigraphic culture of the mid-3rd to early 5th century was still quite “antique” in character; and as it also shows a number of peculiar features, it is certainly correct to give it a specific label, namely “late antique epigraphy”.

It is much more difficult to evaluate the following phase of the (later) 5th and 6th centuries. From a structural point of view (which I cannot explain in detail here) the majority of recent scholarship (including myself) argues that this period should in many respects still be considered as part of Antiquity ( ), and that the decisive “break” between Antiquity and the Middle Ages (both in the West and in the East) should be located somewhere in the late 6th or early 7th centuries.43 But is this also true for the epigraphic practices of this period? Are they still to be qualified as “late antique”? In a certain sense the answer could well be no, taking into account that decisive characteristics of the ancient epigraphic habit like the “civic inscriptions” had by now disappeared more or less completely – and this is even true for regions which had been remarkably conservative in their epigraphic practices during the 4th century like Southern Italy and especially Africa.44 It has to be stressed at this point that the pronounced changes in the epigraphic culture of Africa commenced during the second and third decades of the 5th century, i.e. well before the Vandal invasion of AD 429, the consequences of which have furthermore been re-evaluated in recent scholarship whereby more stress is now put on continuity than on disruptions caused by this event.45 Starting from these observations one could advance the thesis that “late antique epigraphy” in the sense defined above had already come to an end by the early or mid-5th century.

It is also interesting to note that in many regions no clear dividing line can be detected between the quantitatively reduced epigraphic record of the later 5th and 6th centuries, which was restricted to a few types of inscriptions, and the epigraphic material from the following early medieval period, as has been observed in Merovingian Gaul or in Lombard Italy. This statement is especially true for Spain, where the funerary epigraphic habit continued into the Visigothic period (until AD 711) without any discernible break both in the phrasing of inscriptions and in their layout and decoration. In certain areas and towns like Mérida we encounter a distinct regional epigraphic culture from the later 4th century onwards which was characterized by the habit of indicating the moment of the erection of an epitaph by referring to the so-called “Hispanic era”; and this in turn enables us to date many of these documents very closely.46 Many of these funerary monuments can thus be assigned to the 5th and 6th centuries. If we did not have these exact dates, we would probably not have guessed that the inscriptions are so late, as they don’t differ in any respect from earlier ones (◉18).

© C. Witschel.

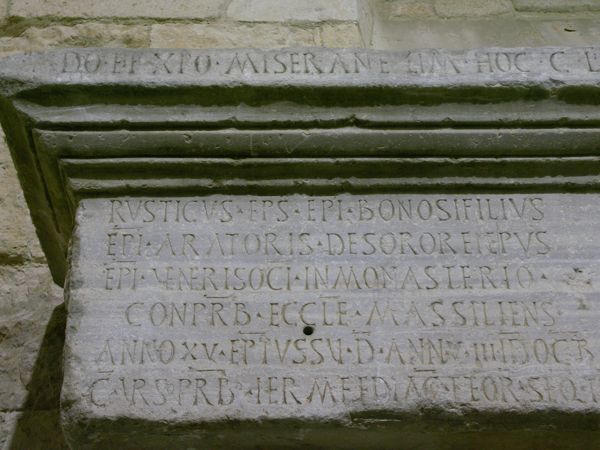

The epigraphy of the 5th and 6th centuries can thus be qualified as a “liminal phenomenon” between Antiquity and the Middle Ages. But on the other hand, it must be stressed that the period of the (later) 5th and 6th centuries at least in some regions (Italy, parts of Africa, but also Spain) was still characterized by a relatively high number of inscriptions – much higher, as far as I can see, than in the following period of the 7th and early 8th centuries. By now these inscriptions were almost exclusively either epitaphs or texts (often in mosaic) commemorating the construction or decoration of church buildings, but they still showed some characteristic elements of the earlier periods both in their formulae and in their design. For example, such inscriptions often named members of the non-clerical and clerical elite with their traditional titles and indications of rank like vir spectabilis or vir honestus etc. (◉19). Even in clearly Christian contexts like churches at least some parts of the traditional formulae were still in use, as can be seen in building inscriptions ordered by bishops like Rusticus of Narbonne or Eufrasius of Poreč (◉20, 21), who – in a well-known fashion – used the (interior) space of a church to inscribe their name in various and very conspicuous ways.47 The many small mosaic inscriptions on the floor of churches in North Eastern Italy are another interesting example for this phenomenon: they certainly conveyed new Christian ideas and values especially about donating money to the church in order to gain salvation in afterlife; but they also commemorated concrete contributions by members of the Christian community, even naming the exact number of square feet of mosaic floor a certain person had paid for.48 Their design and placement within the churches seems to indicate that they were still directed towards a rather large audience and were meant to be read or at least to be looked at; and in order to attract the attention of potential observers they were carefully designed with golden letters, red underlines and so forth (◉22). Taking these features into account one can postulate that some lines of continuity connected the epigraphic practice of this period with the earlier, “ancient” one. In conclusion I would therefore like to propose that the epigraphic habit of the liminal period of the 5th and 6th centuries might still be considered as a part of “late antique epigraphy” – but this proposal is certainly open for discussion.

Inscr. It. X 2, 81; Date: Mid-6th c. AD; © C. Witschel.

Notes

- A. Donati (ed.), La terza età dell’epigrafia; Colloquio AIEGL Bologna 1986, Faenza, 1988; K. Bolle, C. Machado, C. Witschel (ed.), The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity, Stuttgart, 2017.

- See, however, the very useful recent survey by I. Tantillo, “Defining Late Antiquity through Epigraphy?”, in: R. Lizzi Testa (ed.), Late Antiquity in Contemporary Debate, Newcastle, 2017, p. 56-77.

- Research for this paper was carried out within the framework of the CRC 933 “Material Text Cultures. Materiality and Presence of Writing in Non-Typographic Societies” (see https://www.materiale-textkulturen.de [last accessed 02/03/2023]) at the University of Heidelberg, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

- Cf., for example, the attempt of a definition presented by S. Panciera, “What is an Inscription? Problems of Definition and Identity of an Historical Source”, ZPE, 183, 2012, p. 1-10.

- In this respect we can see some differences to other kinds of written artefacts which were omnipresent in ancient cities, like texts scratched into or painted on walls (“graffiti” and “dipinti”). For the display of writing and the creation of Schrifträume, however, these sorts of texts were also important, as has been shown for Pompei: P. Lohmann, Graffiti als Interaktionsform. Geritzte Inschriften in den Wohnhäusern Pompejis, Berlin-New York, 2018; F. Opdenhoff, Die Stadt als beschriebener Raum. Die Beispiele Pompeji und Herculaneum, Berlin-Boston-München, 2021. Late antique graffiti have only recently attracted the attention of scholarship; for the East, see the numerous studies by Charlotte Roueché, e.g. ead., “Written Display in the Late Antique and Byzantine City”, in: Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Byzantine Studies London 2006, E. Jeffreys (ed.), Aldershot, 2006, p. 235-253; for the West, cf. M.A. Handley, “Scratching as Devotion: Graffiti, Pilgrimage and Liturgy in the Late Antique and Early Medieval West”, in: The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity, op. cit. (n. 1), p. 555-593.

- The question of “restricted access” to epigraphic monuments has been dealt with by the papers in T. Frese, W.E. Keil, K. Krüger (ed.), Verborgen, unsichtbar, unlesbar – zur Problematik restringierter Schriftpräsenz, Berlin-Boston, 2014.

- The level of literacy (or, for that matter, illiteracy) in ancient societies is a hotly debated topic, following the seminal book by W.V. Harris, Ancient Literacy, Cambridge/MA-London, 1989. Studies written in response to his theses (e.g. the contributions to A. Bowman, G. Woolf (ed.), Literacy and Power in the Ancient World, Cambridge, 1994), have tended to be more optimistic than Harris with regard to the level of (basic) literacy in the Roman world; nevertheless, it seems clear that we have to reckon with large numbers of illiterates even in the cities.

- This quality of an ancient inscription as “monuments” has been demonstrated in many studies by Werner Eck, collected in id., Monument und Inschrift. Gesammelte Aufsätze zur senatorischen Repräsentation in der Kaiserzeit (ed. by W. Ameling, J. Heinrichs), Berlin-New York, 2010. Cf. now the papers in I. Berti et al. (ed.), Writing Matters. Presenting and Perceiving Monumental Inscriptions in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, Berlin-Boston, 2017, and in A. Petrović, I. Petrović, E. Thomas (ed.), The Materiality of Text: Placement, Perception, and Presence of Inscribed Texts in Classical Antiquity, Leiden-Boston, 2019, esp. K. Bolle, Inscriptions between Text and Texture: Inscribed Monuments in Public Spaces – A Case Study at Late Antique Ostia, p. 348-379.

- For the much-discussed phenomenon of the “epigraphic habit” in Antiquity, see R. MacMullen, “The Epigraphic Habit in the Roman Empire”, AJPh, 103, 1982, p. 233-246; G. Woolf, “Monumental Writing and the Expansion of Roman Society in the Early Empire”, JRS, 86, 1996, p. 22-39; E.A. Meyer, “Epigraphy and Communication”, in: The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World, (ed.) M. Peachin, Oxford, 2011, p. 191-226; F. Beltrán-Lloris, “The ‘Epigraphic Habit’ in the Roman World”, in: The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy, (ed.) C. Bruun, J. Edmondson, Oxford, 2015, p. 131-148. Cf. also the collected studies on “Roman epigraphic culture” by Géza Alföldy: id., Die epigraphische Kultur der Römer. Studien zur ihrer Bedeutung, Entwicklung und Erforschung, (ed.) A. Chaniotis, C. Witschel, Stuttgart, 2018.

- On the role of Augustus for the use of inscriptions as a medium of self-representation and communication, see the ground-breaking study by G. Alföldy, “Augustus und die Inschriften: Tradition und Innovation. Die Geburt der imperialen Epigraphik”, Gymnasium, 98, 1991, p. 289-324 [= Alföldy, Die epigraphische Kultur der Römer, op. cit. (n. 9), p. 73-102]. For the quantitative development of the epigraphic culture in the Latin West during the 1st to 3rd centuries AD, see S. Mrozek, “À propos de la répartition chronologique des inscriptions latines dans le Haut-Empire”, Epigraphica, 35, 1973, p. 113-118.

- The public character of many epigraphic monuments is discussed by C. Witschel, “Epigraphische Monumente und städtische Öffentlichkeit im Westen des Imperium Romanum”, in: W. Eck, P. Funke (ed.), Öffentlichkeit – Monument – Text. Akten des XIV Congressus Internationalis Epigraphiae Graecae et Latinae, Berlin, 2012, Berlin-Boston, 2014, p. 105-133.

- The details of the production of Roman inscriptions are exhibited by G.C. Susini, The Roman Stonecutter: An Introduction to Latin Epigraphy, Oxford, 1973; I. Di Stefano Manzella, Mestiere di epigrafista. Guida alla schedatura del materiale epigrafico lapideo, Roma, 1987. A remarkable phenomenon was the use of gilded letters (litterae aureae) for prominent public inscriptions; cf. G. Alföldy, “Der Glanz der römischen Epigraphik: litterae aureae”, in: id., Die epigraphische Kultur der Römer, op. cit. (n. 9), p. 117-138.

- The locus classicus is Petron. 58.7, where a libertus is made to say: lapidarias litteras scio; cf. M. Corbier, “L’écriture dans l’espace public romain”, in: L’Urbs. Espace urbain et histoire (Ier siècle av. J.-C.–IIIe siècle ap. J.-C.). Actes du Colloque Roma 1985, Roma-Paris, 1987, p. 27-60 [= ead., Donner à voir, donner à lire. Mémoire et communication dans la Rome ancienne, Paris, 2006, p. 53-75].

- This problem is treated in more detail in C. Witschel, “Die epigraphische und statuarische Ausstattung von Platzanlagen (fora) im römischen Germanien”, in: Das große Forum von Lopodunum, (ed.) A. Hensen, Edingen-Neckarhausen, 2016, p. 91-152.

- See the critical remarks by C. Roueché, C. Sotinel, “Christian and Late Antique Epigraphies”, in: The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity, op. cit. (n. 1), p. 503-514. This re-evaluation of earlier models does not diminish the value of studies like that of C. Carletti, Epigrafia dei cristiani in occidente dal III al VII secolo. Ideologia e prassi, Bari, 2008.

- For the evolution of the epigraphic habit in Late Antiquity, see C. Witschel, “Der epigraphic habit in der Spätantike: Das Beispiel der Provinz Venetia et Histria”, in: Die Stadt in der Spätantike – Niedergang oder Wandel?, J.-U. Krause, C. Witschel (ed.), Stuttgart, 2006, p. 359-411; eund., “The Epigraphic Habit in Late Antiquity: An Electronic Archive of Late Roman Inscriptions Ready for Open Access”, in: Latin on Stone: Epigraphic Research and Electronic Archives, F. Feraudi-Gruénais (ed.), Plymouth, 2010, p. 77-97; D.E. Trout, “Inscribing Identity: The Latin Epigraphic Habit in Late Antiquity”, in: A Companion to Late Antiquity, (ed.) P. Rousseau, Oxford, 2009, p. 170-186 as well as the contributions to the collected volumes cited in n. 1. For the concomitant changes in the “statue habit”, see C. Machado, “Public Monuments and Civic Life: The End of the Statue Habit in Italy”, in: Le trasformazioni del V secolo. L’Italia, i Barbari e l’Occidente romano, (ed.) P. Delogu, S. Gasparri, Turnhout, 2010, p. 237-257 and the papers in R.R.R. Smith, B. Ward-Perkins (ed.), The Last Statues of Antiquity, Oxford, 2016, presenting the results of the important collaborative project “The Last Statues of Antiquity” (LSA: http://laststatues.classics.ox.ac.uk/ [last accessed 02/03/2023]).

- Even within a given region the sub-regional differences could be marked, as is demonstrated by the diffusion and character of funerary inscriptions in late antique North Africa; cf. N. Duval, “L’épigraphie funéraire chrétienne d’Afrique: traditions et ruptures, constantes et diversités”, in: La terza età, op. cit. (n. 1), p. 265-314; now updated by S. Ardeleanu, “L’épigraphie funéraire de l’Afrique du Nord tardo-antique: bilan, problèmes et perspectives de la recherche récente (1988-2018)”, in: S. Aounallah, (ed.) A. Mastino, L’epigrafia del Nord Africa: novità, riletture, nuove sintesi, Faenza, 2020, p. 639-651.

- This aspect has been stressed by F. Kolb, “Überlegungen zur spätantiken und byzantinischen Besiedlung Zentrallykiens”, in: Klassisches Altertum, Spätantike und frühes Christentum. Adolf Lippold zum 65. Geburtstag gewidmet, (ed.) K. Dietz, D. Hennig, H. Kaletsch, Würzburg, 1993, p. 609-635; cf. also the short overviews of the divergent epigraphic landscapes in late antique Asia minor presented by S. Mitchell, “The Christian Epigraphy of Asia minor in Late Antiquity”, in: The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity, op. cit. (n. 1), p. 271-286; and by S. Destephen, “The Process of ‘Byzantinization’ in Late Antique Epigraphy”, in: M.D. Lauxtermann, I. Toth (ed.), Inscribing Texts in Byzantium: Continuities and Transformations, London-New York, 2020, p. 17-34.

- Northern Syria: G. Tate, “À titre de comparaison, les manifestations économiques de la crise dans le Nord de la Syrie”, in: (ed.) J.‑L. Fiches, Le IIIe siècle en Gaule Narbonnaise. Données régionales sur la crise de l’Empire, Antibes, 1996, p. 71-81. Palestine: L. Di Segni, “Late Antique Inscriptions in the Provinces of Palaestina and Arabia: Realties and Change”, in: The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity, op. cit. (n. 1), p. 287-320.

- The use of spolia was a very wide-spread phenomenon in the late antique world, and it has therefore been intensively studied in recent years. Cf., for example, the papers in S. Altekamp, C. Marcks-Jacobs, P. Seiler (ed.), Perspektiven der Spolienforschung 1: Spoliierung und Transposition, Berlin-Boston, 2013. Epigraphic monuments were also reused in great numbers, both for engraving new inscriptions and as building material; cf. R. Coates-Stephens, “Epigraphy as Spolia – The Reuse of Inscriptions in Early Medieval Buildings”, PBSR, 70, 2002, p. 275-296; C. Machado, “Dedicated to Eternity? The Reuse of Statue Bases in Late Antique Italy”, in: The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity, op. cit. (n. 1), p. 323-361. For the situation in the East, see A.M. Sitz, “Hiding in Plain Sight: Epigraphic Reuse in the Temple-Church at Aphrodisias”, JLA, 12, 2019, p. 136-168.

- This expression has been used by S. Orlandi, “Orations in Stone”, in: The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity, op. cit. (n. 1), p. 407-425. Cf. also V. Neri, “L’elogio della cultura e l’elogio della virtù politiche nell’epigrafia latina IV secolo d.C.”, Epigraphica, 43, 1981, p. 175-201; J. Weisweiler, “From Equality to Asymmetry: Honorific Statues, Imperial Power, and Senatorial Identity in Late-Antique Rome”, JRA, 25, 2012, p. 319-350.

- The classic study on late antique metric inscriptions in the East is by L. Robert, Épigrammes du Bas-Empire, Paris, 1948; cf. also E. Sironen, “The Epigram Habit in Late Antique Greece”, in: The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity, op. cit. (n. 1), p. 449-471. Verse inscriptions were also popular in elite circles in the West, especially in funerary contexts, see L. Grig, “Cultural Capital and Christianization: The Metrical Inscriptions of Late Antique Rome”, in: ibid., p. 427-447; but also in ecclesiastical spaces, as shown by the work of Pope Damasus: M. Löx, Monumenta sanctorum. Rom und Mailand als Zentren des frühen Christentums: Märtyrerkult und Kirchenbau unter den Bischöfen Damasus und Ambrosius, Wiesbaden, 2013; D.E. Trout, Damasus of Rome, The Epigraphic Poetry: Introduction, Texts, Translations, and Commentary, Oxford, 2015.

- These aspects are explored in a recent monograph on the late antique inscriptions of Italy: K. Bolle, Materialität und Präsenz spätantiker Inschriften. Eine Studie zum Wandel der Inschriftenkultur in den italienischen Provinzen, Berlin-Boston, 2019.

- Possible explanations for this phenomenon have been discussed by B. Borg, C. Witschel, “Veränderungen im Repräsentationsverhalten der römischen Eliten während des 3. Jhs. n. Chr.”, in: Inschriftliche Denkmäler als Medien der Selbstdarstellung in der römischen Welt, (ed.) G. Alföldy, S. Panciera, Stuttgart, 2001, p. 47-120, where some hypotheses which were once popular (like a general “economic decline”) are rejected.

- For the following points, see C. Witschel, “Hispania, Gallia, and Raetia”, in: The Last Statues of Antiquity, op. cit. (n. 16), p. 69-79.

- For the late antique elite culture of Aquitania, known from both literary and archaeological sources, see H. Sivan, Ausonius of Bordeaux: Genesis of a Gallic Aristocracy, London, 1993; C. Balmelle, Les demeures aristocratiques d’Aquitaine. Société et culture de l’Antiquité tardive dans le Sud-Ouest de la Gaule, Bordeaux, 2001.

- Cf. J. Végh, “Inschriftenkultur und Christianisierung im spätantiken Hispanien: Ein Überblick”, in: The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity, op. cit. (n. 1), p. 55-110. For the development of the epigraphic habit in Hispania during the 3rd and early 4th centuries, see C. Witschel, “Hispania en el siglo III”, in: Hispaniae. Las provincias hispanas en el mundo romano, (ed.) J. Andreu Pintado, J. Cabrero Piquero, I. Rodà de Llanza ,Tarragona, 2009, 473-503; G. Alföldy, “Tausend Jahre epigraphische Kultur im römischen Hispanien: Inschriften, Selbstdarstellung und Sozialordnung”, Lucentum, 30, 2011, p. 187-220 [= Alföldy, Die epigraphische Kultur der Römer, op. cit. (n. 9), p. 243-277].

- The late antique inscriptions of Lepcis magna are explored in detail in I. Tantillo (ed.), Leptis Magna. Una città e le sue iscrizioni in epoca tardoromana, Cassino, 2010; id., “La trasformazione del paesaggio epigrafico nelle città dell’Africa romana, con particolare riferimento al caso die Leptis magna (Tripolitana)”, in: The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity, op. cit. (n. 1), p. 213-270; see further http://inslib.kcl.ac.uk/irt2009 and https://lepcismagna.materiale-textkulturen.de/ [last accessed 02/03/2023]. For late antique “civic inscriptions” in North Africa in general, see below n. 41.

- Venetia et Histria: Witschel, Das Beispiel der Provinz Venetia et Histria, op. cit. (n. 16); id., “La trasformazione delle forme di rappresentazione epigrafica nelle città dell’Italia centro-settentrionale in età tardoantica”, in: Voce concordi’. Scritti per Claudio Zaccaria, (ed.) F. Mainardis, Trieste, 2016, p. 747-755. Tuscia et Umbria: K. Bolle, “Spätantike Inschriften in Tuscia et Umbria: Materialität und Präsenz”, in: The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity, op. cit. (n. 1), p. 147-212 (see further: https://tusciaetumbria.materiale-textkulturen.de [last accessed 02/03/2023]). Apulia et Calabria: C. Carletti, D. Nuzzo, “La terza età dell’epigrafia nella provincia Apulia et Calabria: Prolegomena”, VetChrist, 44, 2007, p. 189-224; M. Silvestrini, “Le civitates dell’Apulia et Calabria: aspetti della documentazione epigrafica tardoantica”, in: Paesaggi e insediamenti urbani in Italia meridionale fra Tardoantico e Altomedioevo II. Atti del Secondo Seminario sul Tardoantico e l’Altomedioevo in Italia Meridionale Foggia – Monte Sant’Angelo 2006, (ed.) G. Volpe, R. Giuliani, Bari, 2010, p. 61-76. For Campania, see the example of Puteoli: G. Camodeca, “Ricerche su Puteoli tardoromana (fine III-IV secolo)”, Puteoli, 4/5, 1980/81, p. 59-128. For the general picture, cf. G.A. Cecconi, Governo imperiale e élites dirigenti nell’Italia tardoantica. Problemi di storia politico-amministrativa, 270-476 d.C., Como, 1994.

- On the epigraphic and statuary monuments on the fora of late antique Italy and especially in Aquileia, see C. Witschel, “Statuen auf spätantiken Platzanlagen in Italien und Africa”, in: Statuen in der Spätantike, (ed.) F.A. Bauer, C. Witschel, Wiesbaden, 2007, p. 113-169; eund., “Inschriften und Inschriftenkultur der konstantinischen Zeit in Aquileia, Aquileia Nostra, 83, 2012/13 [2015], p. 29-66.

- The functions of milestones in Late Antiquity have been treated by C. Witschel, “Meilensteine als historische Quelle? Das Beispiel Aquileia”, Chiron, 32, 2002, p. 325-393; cf. also A. Kolb, “Römische Meilensteine: Stand der Forschung und Probleme”, in: Siedlung und Verkehr im römischen Reich. Römerstraßen zwischen Herrschaftssicherung und Landschaftsprägung. Akten des Kolloquiums zu Ehren von H.E. Herzig, (ed.) R. Frei-Stolba, Bern, 2001, Bern et al., 2004, p. 135-155; C. Tiussi, “Un ritrovamento di miliari nel greto del fiume Torre a Villesse (Gorizia) e la via Aquileia – Iulia Emona”, Aquileia Nostra, 81, 2010, p. 277-360.

- The development of the epigraphic habit in (northern) Italy in the 5th and 6th centuries and especially during the Ostrogothic period is described by C. Witschel, “Die Städte Nord- und Mittelitaliens im 5. und 6. Jh. n. Chr.”, in: Theoderich der Große und das gotische Königreich in Italien, (ed.) H.-U. Wiemer, Berlin-Boston, 2020, p. 37-61.

- For inscriptions that mention king Theoderic, see P. Guerrini, “Theodericus rex nelle testimonianze epigrafiche”, in: Temporis signa. Archeologia della tarda antichità e del medioevo, 6, 2011, p. 133-174.

- On late antique funerary inscriptions, see comprehensively C.R. Galvão-Sobrinho, “Funerary Epigraphy and the Spread of Christianity in the West”, Athenaeum, 83, 1995, p. 431-462; M.A. Handley, Death, Society and Culture. Inscriptions and Epitaphs in Gaul and Spain, AD 300-750, Oxford, 2003; L. Clemens, H. Merten, C. Schäfer (ed.), Frühchristliche Grabinschriften im Westen des Römischen Reiches, Trier, 2015; and a forthcoming volume edited by S. Ardeleanu and J.C. Cubas Díaz (Funerary Landscapes of the Late Antique Oecumene. Contextualizing Archaeological and Epigraphic Evidence of Mortuary Practices). The late antique funerary inscriptions of the Greek East have been (partially) collected in a special database: Inscriptiones Christianae Graecae (ICG). A Digital Collection of Greek Early Christian Inscriptions from Asia Minor and Greece (http://www.epigraph.topoi.org/ [last accessed 02/03/2023]).

- For churches as spaces for the presentation of inscriptions (both votive and funerary), see A.M. Yasin, Saints and Church Spaces in the Late Antique Mediterranean. Architecture, Cult, and Community, Cambridge, 2009; S.V. Leatherbury, Inscribing Faith in Late Antiquity: Between Reading and Seeing, London-New York, 2020; and as a case study S. Ardeleanu, “Directing the Faithful, Structuring the Sacred Space: Funerary Epigraphy in its Archaeological Context in Late-Antique Tipasa”, JRA, 31, 2018, p. 475-501.

- For the model of “interiorization”, see M.F. Hansen, “Meanings of Style. On the ‘Interiorization’ of Late Antique Architecture”, in: J. Fleischer, J. Lund, M. Nielsen (ed.), Late Antiquity – Art in Context, Copenhagen, 2001, p. 71-83; F.A. Bauer, C. Witschel, “Statuen in der Spätantike”, in: Statuen in der Spätantike, op. cit. (n. 30), p. 1-24 (esp. 12f.); F.A. Bauer, “Die Stadt als religiöser Raum in der Spätantike”, Archiv für Religionsgeschichte, 10, 2008, p. 179-206.

- On the mosaic inscriptions on the floors (and sometimes also on the walls) of churches in Northern Italy, see J.-P. Caillet, L’évergétisme monumental chrétien en Italie et à ses marges d’après l’épigraphie des pavements de mosaique (IVe-VIIe s.), Roma-Paris, 1993; A. Zettler, Offerenteninschriften auf den frühchristlichen Mosaikfußböden Venetiens und Istriens, Berlin-New York, 2001; K. Bolle, S. Westphalen, C. Witschel, “Mosaizieren”, in: Materiale Textkulturen. Konzepte – Materialien – Praktiken, (ed.) T. Meier, M.R. Ott, R. Sauer, Berlin-Boston, 2015, p. 485-501; R. Haensch, “Zwei unterschiedliche epigraphische Praktiken: Kirchenbauinschriften in Italien und im Nahen Osten”, in: The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity, op. cit. (n. 1), p. 535-554. See further https://mosaikinschriften.materiale-textkulturen.de/ [last accessed 02/03/2023].

- For the late antique epigraphic and statuary monuments of Aphrodisias, see C. Roueché, Aphrodisias in Late Antiquity: The Late Roman and Byzantine Inscriptions, electronic second edition: http://insaph.kcl.ac.uk/ala2004/index.html [last accessed 02/03/2023]; R.R.R. Smith, “Late Antique Portraits in a Public Context: Honorific Statuary at Aphrodisias in Caria, A.D. 300-600”, JRS, 89, 1999, p. 155-189; eund., “Statue Life in the Hadrianic Baths at Aphrodisias, AD 100-600: Local Context and Historical Meaning”, in: Statuen in der Spätantike, op. cit. (n. 30), p. 203-235.

- See above n. 19.

- See above n. 31.

- These inscriptions have been collected in the massive work of C. Lepelley, Les cités de l’Afrique romaine au Bas-Empire. I: La permanence d’une civilisation municipale. II: Notices d’histoire municipale, Paris, 1979/81; supplemented by id., “Nouveaux documents sur la vie municipale dans l’Afrique romaine tardive (éléments d’un supplément épigraphique aux Cités de l’Afrique romaine au Bas-Empire)”, in: Actes du VIIIe colloque international sur l’histoire et l’archéologie de l’Afrique du Nord, Tabarka 2000: L’Afrique du nord antique et médiévale, (ed.) M. Khanoussi, Tunis, 2003, p. 215-228.

- The idea that public places in late antique cities were to a certain extent religiously “neutral” spaces has been developed with special regard to the epigraphic monuments presented in this context: C. Lepelley, “Le lieu des valeurs comunes. La cité terrain neutre entre païens et chrétiens dans l’Afrique romaine tardive”, in: Idéologies et valeurs civiques dans le monde romain. Hommage à C. Lepelley, (ed.) H. Inglebert, Paris, 2002, p. 271-285; id., “De la réaction païenne à la sécularisation: la témoignage d’inscriptions municipales romano-africaines tardives”, in: Pagans and Christians in the Roman Empire: The Breaking of a Dialogue (IVth-VIth Century A.D.). Proceedings of the International Conference at the Monastery of Bose 2008, (ed.) P. Brown, R. Lizzi Testa, Wien-Berlin, 2011, p. 273-289; C. Machado, “Religion as Antiquarianism: Pagan Dedications in Late Antique Rome”, in: Dediche sacre nel mondo greco-romano. Diffusione, funzioni, tipologie, (ed.) J. Bodel, M. Kajava, Roma, 2009, p. 331-354; C. Witschel, “Alte und neue Erinnerungsmodi in den spätantiken Inschriften Roms”, in: Rom in der Spätantike: Historische Erinnerung im städtischen Raum, (ed.) R. Behrwald, C. Witschel, Stuttgart, 2012, p. 357-406. It has, however, been observed that even in traditionally styled honorific inscriptions Christian elements could be included: A. Avdokhin, Y. Shakhov, “Christianizing Statues Unawares? Imperial Imagery and New Testament Phrasing in a Late Antique Honorific Inscription (IEph 4.1301)”, ZPE, 216, 2020, p. 55-68.

- For recent discussions on the periodization of Late Antiquity (including the – problematic – concept of a “long” Late Antiquity), see A. Marcone, “A Long Late Antiquity? Considerations on a Controversial Periodization”, JLA, 1, 2008, p. 4-19; C. Ando, “Decline, Fall, and Transformation”, ibid., p. 31-60.

- There are only a very few (but remarkable) “outliers”, like an inscription from Justinianic Africa (Y. Modéran, “La renaissance des cités dans l’Afrique du VIe siècle d’après une inscription récemment publiée”, in: La fin de la cité antique et le début de la cité médiévale. De la fin du IIIe siècle à l’avènement de Charlemagne, (ed.) C. Lepelley, Bari, 1996, p. 85-114; or a recently discovered epigraphic monument from Tarquinia (Tuscia et Umbria), dated to the year 504; for which see G.A. Cecconi, I. Tantillo, “Un atto di evergetismo municipale in età ostrogota: a proposito di una iscrizione di Tarquinia”, in: L’automne de l’Afrique romaine. Hommages à Claude Lepelley, (ed.) X. Dupuis et. al., Paris, 2021, p. 223-236.

- A good summary of recent work on Vandal North Africa can be found in A.H. Merrills, R. Miles, The Vandals, London, 2010. A large number of late antique funerary inscriptions from North Africa can be dated to the Vandal period (see above n. 17).

- The epigraphic material (mostly funerary inscriptions) from late antique Mérida has been collected in: J.L. Ramírez Sádaba, P. Mateos Cruz, Catálogo de las inscripciones cristianas de Mérida, Mérida, 2000.

- Rusticus of Narbonne: H.-I. Marrou, “Le dossier épigraphique de l’évêque Rusticus de Narbonne”, RAC, 46, 1970, p. 331-349. Eufrasius of Poreč: A. Terry, H. Maguire, Dynamic Splendor. The Wall Mosaics in the Cathedral of Eufrasius at Poreč, University Park, 2007. Eufrasius also made use of monograms exhibiting his name which were placed at central points within the church built by him; for the importance of monograms in late antique churches in general, see F. Stroth, Monogrammkapitelle. Die justinianische Bauskulptur Konstantinopels als Textträger, Wiesbaden, 2021.

- See above n. 37.