The social practices of food may be divided roughly into two main categories. Feasting, that is any kind of celebratory meal, is generally on the side of profusion and overabundance. In contrast, fasting, that is self-deprivation for mostly religious motives, is based on restrictions and restraint. This tension between feasting and fasting was a defining one in the Middle Ages, and this was as true of the realities of food as of its representations. Moreover, both feasting and fasting could be a scene for social distinction and political action: as much as the most splendid banquets, the most extreme fasts could be summoned to signify an elite position or a power issue.1

In the Christian doctrine and practice that were dominant in the medieval West, fasting was implemented during some periods of the week (Fridays, sometimes also Wednesdays and Saturdays) and the year (most importantly during Lent, the 40-days period before Easter), as well as for personal reasons of penance or belonging to particular categories (such as monks and nuns).2 It was not defined as a complete deprivation of food, but as abstinence from certain foodstuffs which were defined as “fat” – mostly meat and, in some case, other products derived from land animals such as eggs, cheese and several kinds of animal fat. Conversely, all fruits, vegetables, cereals and other plants, but also all kinds of fish, were seen as “lean”. This division left a large space for interpretation and distinctive behaviours. As the Middle Ages went on, the development of high sea fishing and the creation of ponds allowed the lay and ecclesiastical elite to have their tables furnished, even in ties of fast, with a rich and varied fare – for instance, with the flesh of sea mammals such as whales and dolphins, which was then considered as fish. Halfway between “proper meat” and fish, the flesh of birds had an ambiguous status, particularly because the Rule of St Benedict did not forbid it.3 Excavations at the priory of La Charité-sur-Loire, in central France, revealed that the monks had access to no less than 27 different species of wild and domestic birds.4 The officially “lean” tables of the Church could indeed be sumptuous!

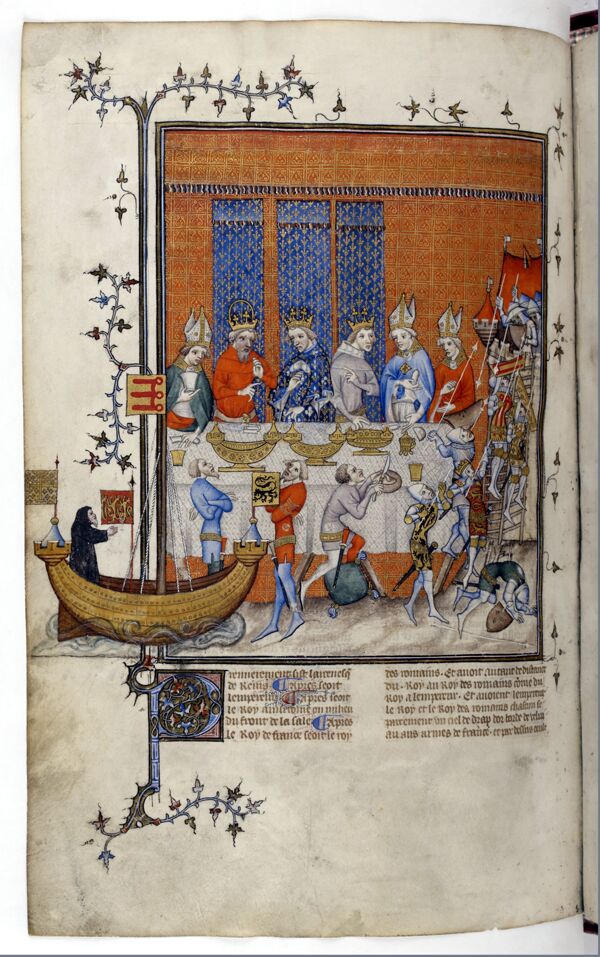

Just as fasting, feasting had its right times and order. Banquets were normally organized for a reason. The great moments of the life cycle (a christening, a wedding, a funeral), the main religious feasts, the arrival of a prestigious guest, the end of a military campaign or of any other difficult task: all these occasions were opportunities for a celebration which normally included a festive meal and/or a drinking party. Feasts were particularly useful occasions for displaying social superiority – through the conspicuous consumption of rare and costly drinks and preparations, but also because they involved complex logistics that went far beyond the necessity to provide prestigious foodstuffs. Indeed, feasts also mobilized a numerous specialized staff (servants, cooks, entertainers…),5 and it could only be organized in proper settings, where the profusion and originality of a lord’s generosity and superiority could best be shown.

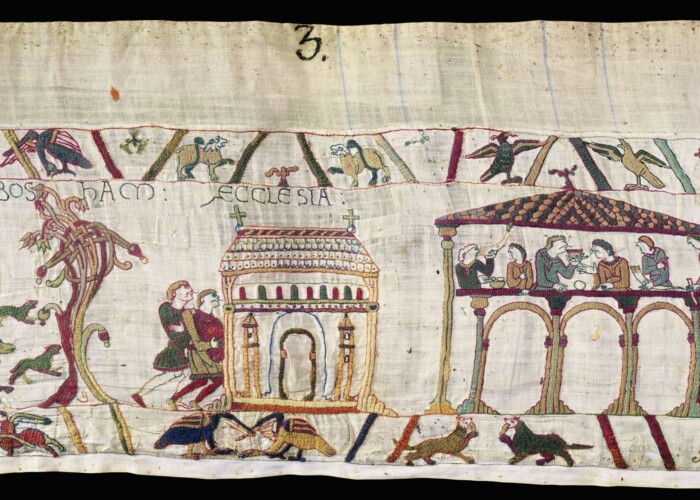

The three main places this kind of social distinction were the kitchen, the hall and the lord’s or lady’s chamber. Kitchens were not frequent in the Middle Ages, either in towns or in the countryside: having a separate room or (quite often) building reserved for cooking can thus be seen as a sign of wealth and prestige.6 The exact form and organization of halls could vary. Yet, from the freestanding wooden rectangular buildings of Anglo-Saxon archaeology, best described in the eighth-century poem Beowulf, to the long upper-floor galleries of early Renaissance castles, through the wide refectories of Benedictine abbeys, halls remained, during the whole medieval period, the most frequent settings for banquets.7 There lords would gather their families, friends and followers, providing them with generous servings of food and (mostly alcoholic) drinks. But, especially from the eleventh century, lords and ladies also liked to entertain their guests in their “private” chambers: there, more informal but politically no less important kinds of meals could take place. The food that was served was not exactly the same there: if quantity ruled in the hall, with generous servings of meat and wine (and, in Northern Europe, ale),8 quality was the hallmark of the chamber, where more precious and imported products could be consumed by a smaller number of eaters – for example in the form of sugar-based confectionery or spiced wines.9

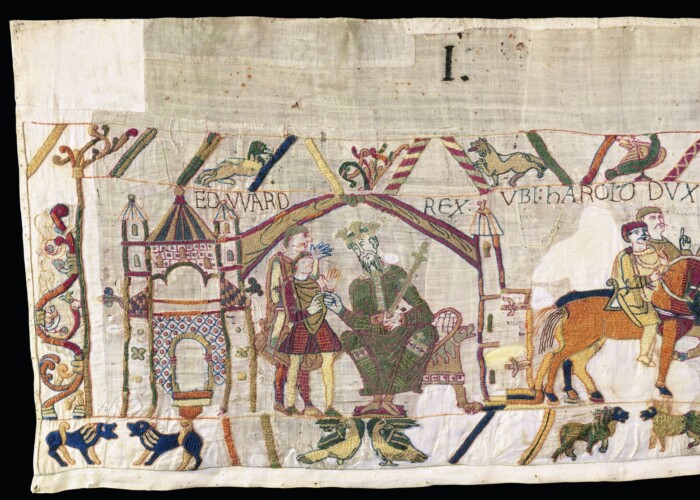

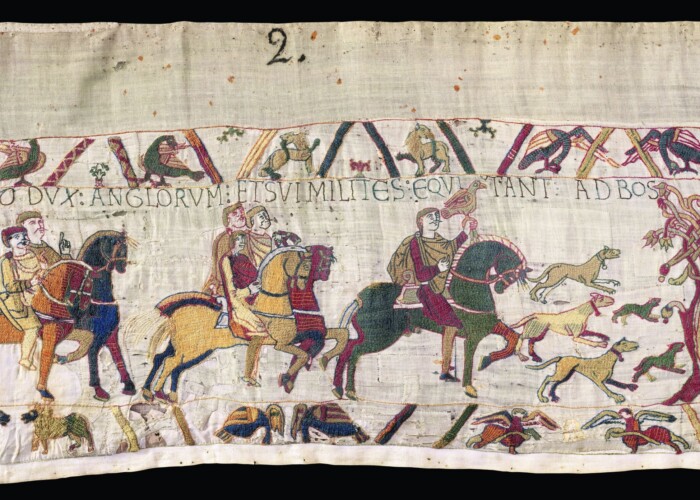

As a place for conspicuous consumption and the spectacular staging of social and political superiority, feasting was also an essential political institution. Medieval government was often conducted by a small number of people who collaborated, more or less willingly, with a ruler who needed to attach them to his service through the public and honourable dispensation of food and drink. For a medieval king, feasting with his men – particularly his warriors – was a way to obtain their fidelity and build with them relations of trust, intimacy and friendship as well as of dependence; and each lord, in his castle, could reproduce this pattern with his own men. Moreover, in the context of mostly itinerant monarchies, the kings’ journeys through their kingdoms would always include feasts: thus did a Carolingian emperor, a Capetian king or a Norman duke make themselves known to their most powerful subjects, creating personal bonds with them that only a shared meal could forge. Each bishop, each abbot, each local lord could boast of having sat at the ruler’s table, sharing his food and drinking his wine. In a time when interpersonal links were at the heart of politics, a feast was where power was performed.

This is why medieval feasting may be described as a ritual or a political liturgy. In a way, it recalls the most topical of food liturgies: that of the eucharist. Like it, medieval political feasting was both horizontal – because the participants partook of the same food and drink – and vertical – expressing hierarchy, fidelity and the power to feed others. Let us not forget that the word “lord”, whether it describes God or a worldly ruler, derives for the Old English term hlafor – literally, the “loaf-warden”, the “bread-keeper”.10

References

- Audoin-Rouzeau, F., 1986: Ossements animaux du Moyen Âge au monastère de La Charité-sur-Loire, Paris.

- Gaillard, M., ed., 2014: L’empreinte chrétienne en Gaule du IVe au IXe siècle, Turnhout.

- Gautier, A, 2006: Le festin dans l’Angleterre anglo-saxonne, Ve-XIe siècle, Rennes.

- Gautier, A., 2009: Alimentations médiévales, Ve-XVIe siècle, Paris.

- Gautier, A., 2016: “Festin et politique : servir la table royale dans le haut Moyen Âge”, in: Settimane di Spoleto LXIII, 2016, 907-937.

- Gautier, A., 2021: “Jeûnes et festins en Europe occidentale, VIIe-XIIe siècle”, in: Quellier, ed., 2021, 427-445.

- Harper-Bill, C. & Harvey, R., ed., 1192: Medieval Knighthood IV, Papers form the fifth Strawberry Hill Conference 1990, Woodbridge.

- Lambert T. & Leggett S., 2022: Food and Power in Early Medieval England: Rethinking Feorm, Anglo-Saxon England, 49, p. 1-47, URL: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/anglo-saxon-england/article/food-and-power-in-early-medieval-england-rethinking-feorm/92CCDA9706D8F0858B0DE4CB4D51FB72

- Laurioux B., 2005: Une histoire culinaire du Moyen Âge, Paris.

- Montanari, M., 1994: The Culture of Food, Oxford.

- Montanari, M., 2015: Mangiare da cristiani: Diete, digiuni, banchetti. Storie di una cultura, Milano.

- Quellier, F., ed., 2021: Histoire de l’alimentation. De la Préhistoire à nos jours, Paris.

- Raga, E., 2014: “L’influence chrétienne sur le modèle alimentaire classique : la question de l’alternance entre banquets, nutrition et jeûne”, in: Gaillard, ed., 2014, 61-87.

- Settimane di Spoleto LXIII, 2016: L’Alimentazione nell’alto medioevo: pratiche, simboli, ideologie, Spoleto, CISAM (Settimane di Studio LXIII).

- Thompson, M., 1995: The Medieval Hall. The Basis of Secular Domestic Life, 600-1600 AD, Aldershot.

- Williams, A., 1992: “A Bell-House and a Burh-Geat: Lordly Residences in England Before the Norman Conquest”, in: Harper-Bill & Harvey ed., 1992, 221-240.