In the seventh century, Isidore of Seville (Etymologiae, XV, iii) defined habitation [habitatio] as having [habere] a place to live, which could be a ‘casa’ (i.e., a rustic hut), a ‘domus’ (the residence for a single family), an ‘aula’ (the royal residence) or an ‘atrium’ (a large and spacious dwelling). The cottage, made of wattles, woven, reeds and twigs, was the most precarious type of dwelling, serving for physical protection against the bad weather. The houses, on the other hand, were elaborate: they had sleeping chambers, a dining room, underground cellars, upper attics, and even a terrace. We must not forget that Isidore deals with etymologies, and his descriptions of places tend to follow an idealized and often ancient reference standard. However, the spatial organization he presents, as well as the vocabulary he uses were in common use during the medieval centuries, and therefore we can make use on his information.

Firstly, it is useful to distinguish rural from urban dwellings and, secondly, aristocratic from non-aristocratic houses, whether in the countryside or in the city. These differences affect the typologies and levels of complexity of the habitats, considered separately or together, which, moreover, depend greatly on the geographical differences between the multiple regions of the Christian West and the historical moments observed. All this makes it very difficult to establish broad and rigid patterns that indicate the variety of ways of inhabiting throughout the medieval millennium.1

Archaeological studies and new historiographical approaches have highlighted, since at least 1990, that even the peasant communities of the High Middle Ages (5th-10th century) were very complex, economically, socially, and politically, although the levels of complexity were quite variable among the regions of the West, thanks to differences in the concentration of wealth and levels of aristocratic domination.2 From the eleventh century onwards, economic growth drives the transformation of villages and cities and entails a population increase, which substantially changed the modes of habitation, whether in cities, where the population triples in size, or in villages, which, in this period, acquired structures politically similar to those found in urban areas.3

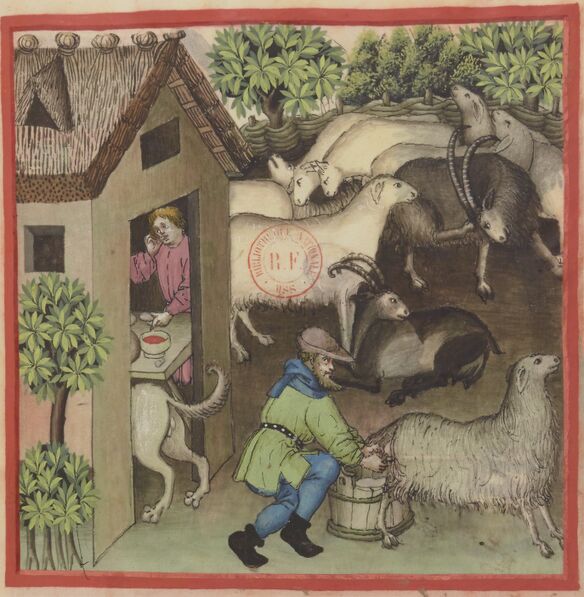

Between the 5th and 10th centuries, in rural areas, there was a predominance of a simplified model of rural house, consisting of a single ground floor, with one or two rooms, built with wood and clay and covered with straw.4 The use of masonry is more evident in the cities, where the scarcity of land, due to the spatial limitation of the walls, forced the construction of houses on several floors, requiring the reinforcement of materials. Before the 11th century, rural houses used to be more dispersed in the terrain and more distant from each other, although it is already possible to identify small settlements formed by several families, in some cases with a complex political organization, with richer and militarized local lineages in charge of the village government. In these houses, the productive activities – handicraft or agricultural work, with their products and working tools – were integrated into the domestic space, who is building even housed small herds, in the lower part of the house, to save space and internal heating.5

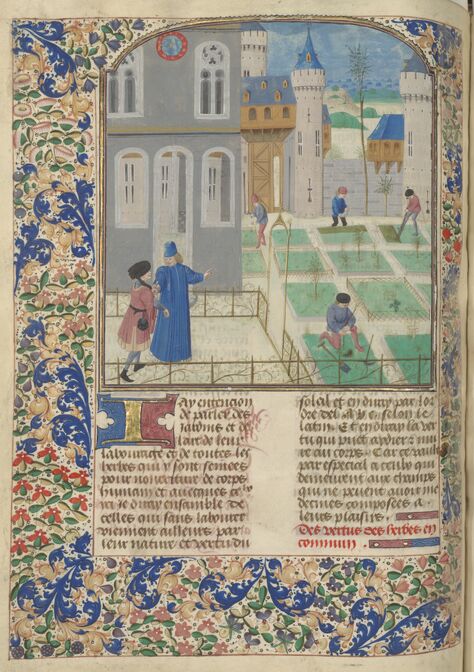

From the eleventh century on, with the growth of the villages, the forms of habitation were transformed: organized in general around a church or a military fortress (the ‘motta’, that is, the ancestor of the castle), the houses of the elite gradually became larger and more sophisticated; for example, the physical separation between the domestic and the productive spaces became more common, whose warehouses, ateliers and storehouses were transferred to a specific area, and the stone constructions became more visible. The manorial residences also became architecturally more elaborate and decorated, even appealing to a militarized aesthetic, in the manner of the manorial motes. The dwellings of the poor peasants, on the contrary, were more modest: small houses, with one or two rooms at most, still built of mud and wood, covered with straw continued to exist and with them the proximity between people, animals, and work tools.6

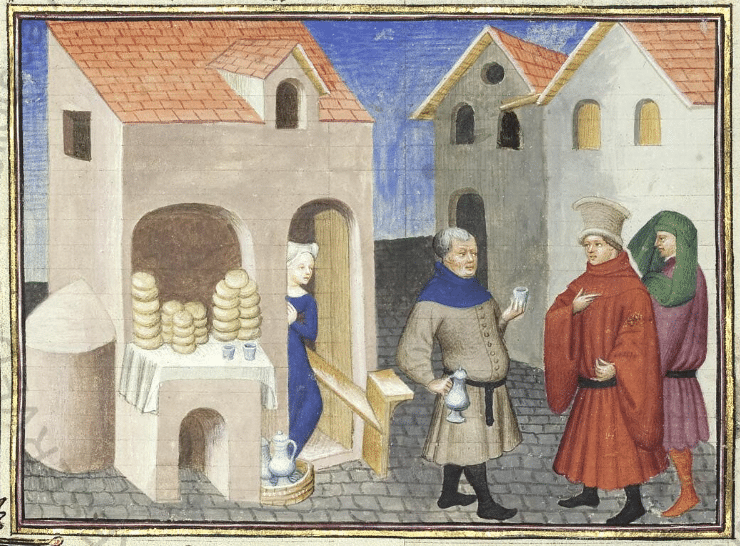

In the cities, the presence of the walls directly affected the residential spaces, because it made the free areas for domestic buildings scarce, forcing the verticalization of the houses. The urban growth is marked by migration from the countryside, and its populations brought with them the rural ways of building and living. It was only in the 13th century that a greater transformation of these practices and techniques was observed, driven by the complete scarcity of intramural space, which no longer allowed the maintenance of vegetable gardens, orchards, and animal nurseries among urban houses.7

With their floor plans perpendicular to the streets, the two-story houses of merchants and artisans kept the shops and workshops on the ground level, while the domestic area was on the upper floor (arcade house or casa porticata, in Italian), generally divided into two parts: the living space, including the kitchen, and the sleeping space. One can also notice in the city the promiscuity between domestic and working place, even though the trades, in the city, were linked to craftsmanship or commerce. The houses of the urban military elite, which were much larger, used to have their plans parallel to the extension of the street, which made the property value higher, since it used more land from the public road, and this characteristic served as a social distinction. Despite this, and the ornamental sophistication found on the façade and inside the elite houses, they also used to employ the bipartite layout, which was the most observable shape of the urban houses in the late Middle Ages.8

Regardless of residential morphologies found during the medieval millennium, the authors of this period, who thought the physical space in consonance with the political sphere, such as Giles of Rome or Salimbene of Parma, insist on presenting us with the connection between the act of inhabiting, the transformation of space and the creation of forms of communal coexistence, which conceives politics as the good management of a common house. This is how the domestic house, and its administration, became relevant to the city, not only as a unit of economic production and consumption, but as a microcosm of society considered globally. Inhabiting was interpreted as an act of transforming a physical space into a human place, connecting people to a land and people to each other. The domestic space was the condition for the city to emerge as community space. In Giles of Rome’s words, a family, when it grew through the generation of grandchildren, was divided into many other houses, which formed neighborhoods, and the neighborhoods, cities, and cities, kingdoms. Everything else depended on the house you lived in as a family. Artists and treatise writers of the Late Middle Ages agreed that well-governed houses generated a just and balanced republic, justifying even city control over private practices of living and inhabiting.

Cote: BnF ms Latin 9333 fl. 57r – online (©Bibliothèque Nationale de France).

References

- Bianchi, G., 2012: “Building, inhabiting and « perceiving » private houses in early medieval Italy”, Arqueología de la Arquitectura, 9, p. 195-212.

- Conde, M., 2011: Construir, Habitar: A casa medieval, Braga.

- Pesez, J.-M., 1998: Archéologie du village et de la Maison rurale au Moye Âge, Lyon.

- Pounds, N., 2005: The Medieval City, Westport/London.

- Wickham, C., 2019: O Legado de Roma, Iluminando a idade das trevas, 400-1000, Campinas.