The analysis of an artefact and its contexts is the “reading” of the object, some archeologists even call it “making the remains speak”. This approach is used to understand the connection between the deceased, their environment, and the artefacts by identifying, dating, and tracing the object’s journey. This scientific approach is used and adapted to all types and categories of archeological remains (ceramics, glass, metal, bone, organic matter, minerals, etc.). However, not all artefacts will be studied in depth for numerous reasons: lack of time, lack of resources, the conservation quality of the pieces, or the size of the studied corpus. To illustrate this chapter, we have chosen to analyze an early medieval ring discovered in France.

The ring was discovered at Jau-Dignac-et-Loirac in Gironde, during an excavation conducted by Isabelle Cartron (Université Bordeaux Montaigne/Ausonius) and Dominque Castex (CNRS/PACEA). It is a remarkable piece of jewelry due to its singularity, and it was an object of investigation. Several researchers were mobilized to identify this solid gold jewel, decorated with a glass paste intaglio.1

The archaeological context

This ring was unearthed in the sepulture 14, at the site of “La Chapelle”, in Jau-Dignac-et-Loirac in Gironde. It was the burial of a young woman aged between 15 and 30 years old, who lays in a sarcophagus set up inside a family church from the early Middle Ages. During the funerals, a knife, and a massive damascene buckle plate, decorated in the “style animalier 2”, were placed beside her.2

This ring is the only one discovered in France3 so far and has a very peculiar shape. The few other discoveries of this type were found in Scandinavia and were made during the Roman period.4 However, the manufacturing techniques and some stylistic elements, such as the columns and the basket bezels, allow us to date back to Jau-Dignac ring to the early Middle Ages.

By cross-referencing the typological data of the objects with the stratigraphy of the site, it was possible to date this burial to the last quarter of the 7th century. The grave can be described as remarkable, both for its topographical location, within the early medieval building, and for the luxury objects that got along with the deceased. This implied that the buried woman had a privileged status, and probably belonged to an elite group that took great care of her remains. These contextual clues are crucial in the ring’s study case, and to the understanding of the link between this object, the deceased, and the sequence of events that took place and led to the burial of the jewel in this environment.

The production phase: the creation of the jewel

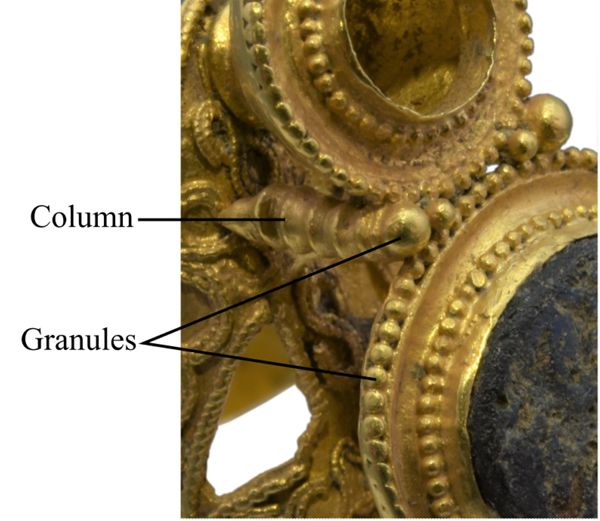

The analysis of the final products makes it possible to trace some of the worker’s actions, who shaped the objects. The structure of the object is the first thing to be analyzed. Then, it can be proven that this ring is made up of several elements that were weld together. The remarkable goldsmith’s work combined several techniques for shaping the metal, such as repoussé, hammering, granulation and filigree.5

- Hammering was used to obtain the body of the ring, made of a thin gold sheet shaped to fit the wearer’s finger.

- The decorative columns on the top are gold embossed sheets, shaped by the indirect impact of a hammer on another shaping tool.

- Granules are placed on top of each column. Granulation is a decoration technique, which consists on applying small metal globules, set singly in a line or a cluster, depending on the desired aesthetic effect. To make a granule, the metal is heated to its melting point and then poured in drops onto powdered charcoal or into the water, the grains are then collected and sorted.

- The ring is also decorated with a pearl filigree, which was very popular in the early Middle Ages. These are gold threads or sheets stretched or folded until a very fine thread was obtained.

Traces of wear and tear: retracing the object’s journey

Now that the manufacturing techniques have been identified, it is possible to study – thanks to the contextual data – the traces that testify the life of the object: wear and repairs.6

- Wear and tear: like any work object, the ring has been subjected to mechanical friction that has partially damaged the decorations. It is also deformed: this is partly due to the wearing of the object, but also because the ring was made of – practically – pure gold, which is a soft metal subject to deformation.

- Traces of repair: according to the traces observed inside the band, this ring was most probably reshaped to fit the fingers of a new wearer.

The archeological data shows that this ring was probably deposited incomplete in the grave: the two elements set in the side baskets were missing.

All of these traces testify to the fact that the object was worn, and was not a piece of jewelry made for the deceased’s funeral. This ring may have been passed on to her, perhaps over several generations, as suggested by the significant traces of wear, as well as the adjustment’s traces of a new wearer. In any case, the journey of this object ended with this young woman death, whom her relatives decided to bury with this jewel7. Whether it is this ring or any other object, the archeological analysis of the product makes it possible to highlight precious clues on the main lines of the object’s itinerary. This work of restitution – which is incomplete because it would be impossible to be exhaustive – allows us to approach many aspects of the past societies’ life.

Read more

Le Marathon des images 2 : « un jour mon prince viendra… » (présentation de la bague de la dame de Jau-Dignac-et-Loirac). 29e minute (présentation de la bague de la dame de Jau-Dignac-et-Loirac). (© Blois, Les rendez-vous de l’histoire. Les vivants et les morts, 10/2023).

References

- Andersson, K., 1985: “Intellektuell import eller romersk dona ?”, TOR, XX, p. 107-148.

- Hadjadj, R., 2005: Bagues mérovingiennes : Gaule du nord, Paris.

- Leroi-Gourhan, A., [1964] 1993: Gesture and Speech, Cambridge.

- Leroi-Gourhan, A., [1945] 2000: Milieu et technique, Paris.

- Mauss, M. [1950] 1968: Sociologie et anthropologie, Paris, URL: http://classiques.uqac.ca/classiques/mauss_marcel/socio_et_anthropo/socio_et_anthropo_tdm.html

- Mauss, M., [1936] 1973: « Techniques of the body », in Economy and Society, 2-1, p. 70-80.

- Renou, J., Poignant, S., 2022: “Des bijoux brisés, trajectoires d’objets précieux durant le haut Moyen Âge : le cas de la sépulture 87 de la nécropole de Chasseneuil-sur-Bonnieure (Charente)”, in: Bernasconi G., Carnino G., Hilaire-Pérez L., Raveux O. (dir.), Les Réparations dans l’Histoire. Cultures techniques et savoir-faire dans la longue durée. Paris, p. 450-461.

- Salin, E., 1959: La civilisation mérovingienne, quatrième partie. Les croyances, conclusions, index général, Paris.

- Young, A., 2010: The Workbench Guide to Jewelry Techniques, London.

Notes

- PIXE analyses at the AGLAE accelerator conducted by M.F Guerra at the C2RMF, UMR 171 of the CNRS.

- See Salin 1959 which explains the “Style animalier” and its origins, p.213-222.

- Hadjadj 2005.

- Andersson 1985.

- See Christie’s article about Ancient techniques of jewelry https://www.christies.com/features/Ancient-jewellery-A-window-onto-ancient-techniques-7757-3.aspx or Young 2010, for a modern and complete guide to techniques that have changed little over the centuries.

- Renou 2022.

- See the chapter “To pass away”.