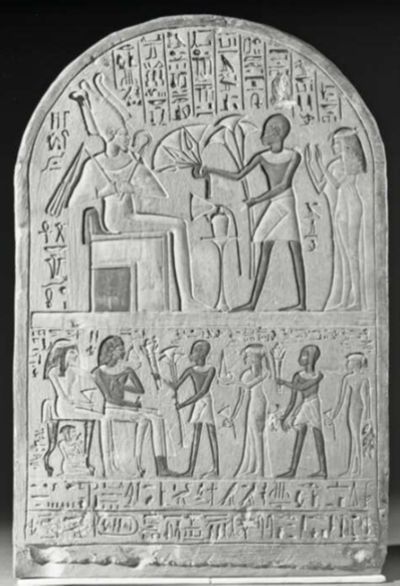

The presence of inscriptions frequently has the effect of eluding the materiality of the artifact. In many fields of knowledge, writing has thus earned a certain amount of autonomy about its physical support, and it became the focus of the analysis. The preponderance of a logocentric tradition in the humanities contributed towards an ontological split between language and its meanings on one side, and materiality on the other. Therefore “reading”, understood as semiotic deciphering of meanings, imposed itself as an equivalent to interpretation. Such was commonly the case among historians, which lead to an imperfect incorporation of the artifacts into the historiographical operation. The prevalence of the written document as the preeminent source which marked the dawn of the field of study in the 19th century ended up engulfing the materiality of writing, even though writing itself is almost entirely dependent on a physical support (only the recent arrival of the digital medias has altered that outlook, even if the material dimension of the digital universe could still be up for discussion). The image has undergone a similar process: its presence invariably nudged the image object towards the field of various kinds of iconographic analysis, eschewing its physical dimension. Nonetheless, the perception of the materiality of the image was more precocious and, until now, more emphatic than the deliberations over the materiality of writing.1

However, in the past few years a strong movement has changed such situation: although writing does derive from an act of intellectual creation, both its existence and its sociocultural role cannot do without a material engagement that articulates body, gesture, tools, and materials.

First and foremost, it is important to keep in mind a fundamental fact eloquently articulated by Christian Mosboek Johannessen and Theo van Leeuwen (2018, 2): “Homo Sapiens is fundamentally a trace-making species. Through-out the course of our history and prehistory, acts of modifying surfaces by adding or removing material, thus leaving traces, have been a fulcrum of cultural practices, whether spiritual, practical, or aesthetic”. Writing is the culturally diversified unfolding of a common behavior inscribed in humans. Therefore, a more productive and exhaustive approach should consider writing as a semiotic phenomenon alongside its biological and physical dimensions, thus allowing “the scientific study of trace-making and trace perception”.

In addition to that, the text’s physical support influences its production, circulation, and reception. For that reason, its materiality both conditions and offers distinct possibilities to the act of writing and reading.2 Under those circumstances, a dimension often disregarded until now, becomes crucial, that of spatiality. To redefine polar opposites – the human being and the matter – implies to consider that “both humans and things are material forms that exist in spatial relationships that both construct and define them. Their materialities exist in topological relation to other materialities.3 Thus, never has the attention towards the archaeological contexts in which the texts were found been as important as it is today. Unfortunately, it is not always that such data is either available or registered adequately.

Another prospect which has recently become more highly regarded is that of writing practices, specifically concerning the field of scribal culture that pertained societies in which chirography held great importance. The role of the scribe, however, has been reevaluated according to a concept of agency which “moves the focus away from intentionality and event and toward practices and processes”.4

In conclusion, the deliberation over the materiality of writing inscribes it into the sensorial universe. Before all else, such considerations retrieve writing’s visual nature and submits it to the same sensorial processes that are generally reserved to the act of observing the images. Likewise, the boundaries between the written word and the phenomena of sound (reading aloud, singing etc.) become less rigid and allow for a more adequate comprehension of the different articulations of word and sound, which underwent cultural shifts across historical time. An important consequence of such deliberation is a greater focus on the occasions in which the initially written word is expressed through performance. Either way, new approaches imply, as suggested by Ingold (2018), considering writing as a visual (optic), auditory (acoustic) and tactile (haptic) phenomenon.

References

- Englehardt, J. & Nakassis, D., 2013: “Individual intentionality, social structure, and material agency in early writing and emerging script technologies”, in: Englehardt, J. (ed.), Agency in ancient writing, Boulder, Colorado, 1-18.

- Ingold, T. (2018) : “Touchlines. Manual inscriptions and haptic perception”, in: Johannessen, C. M. & Leeuwen, T. van (ed.), The materiality of writing. A trace-making perspective, New York, 30-45.

- Johannessen, C. M. & Leeuwen, T. van, 2018: “Introduction”, in: Johannessen, C. M. & Leeuwen, T. van (ed.), The materiality of writing. A trace-making perspective, New York, 1-11.

- Krauss, A., Leipziger, J. & Schücking-Jungblut, 2020: “Material aspects of Reading and text cultures”, in: Krauss, A., Leipziger, J. & Schücking-Jungblut (ed.), Material aspects of reading in ancient and medieval cultures. Materiality, presence and performance, Berlin-Boston, 1-8.

- Neufeld, Ch. & Wagner, R., 2019: “Introduction?, in: Wagner, R., Neufeld, Ch. & Lieb, L. (ed.), Writing beyond pen and parchment. Inscribed objects in medieval european literature, Berlin-Boston, 1-13.

- Rede, M., 2018: “Materiality and history: some reflections”, in: Maynard, E., Velloza, C. & Lemos, R. (ed.), Perspectives on materiality in ancient Egypt – agency, cultural reproduction and change, Oxford, 74-86.