Recently, knowledge of the ancient habitat during Antiquity has benefited from the multiplication of preventive excavations, from the contribution of programmed excavations, but also from data obtained from pedestrian, aerial and geophysical prospection. All these methods have revealed a great diversity of rural habitat, multiple construction techniques and varied decorations.

During the 1st century AD, the countryside of Aquitaine gradually developed a network of farms comprising villae and more modest settlements. The villa, owned by notables, comprised a residential building (pars urbana) and buildings (pars rustica) linked to the exploitation of the estate’s land (fundus), whose soils, generally varied, often had complementary cultivation aptitudes.

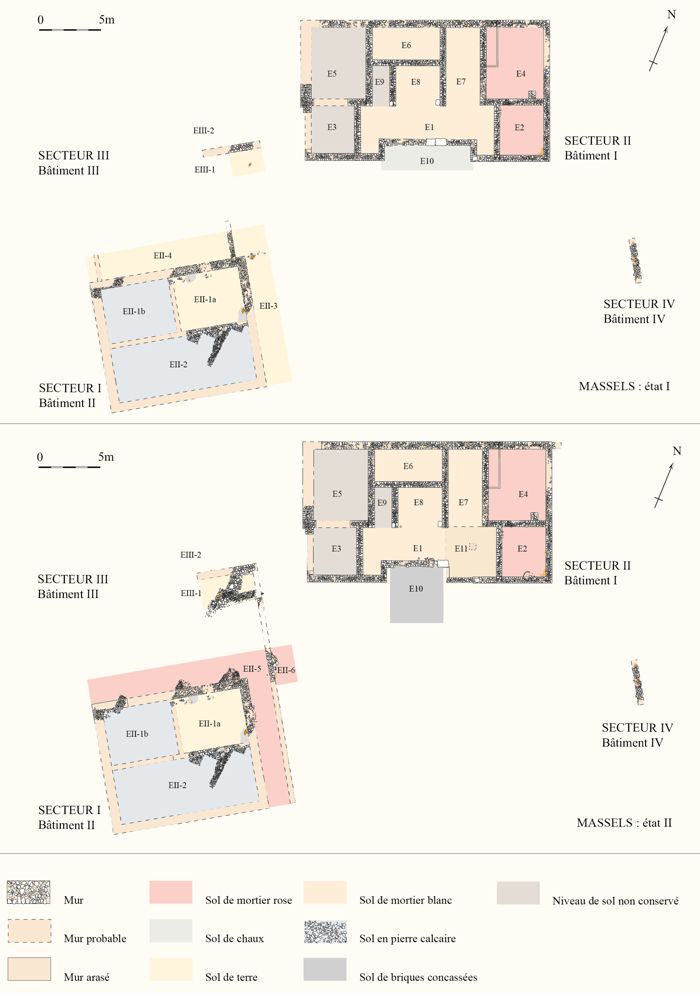

In Aquitaine, recent excavations and aerial revelations have renewed our knowledge of the morphology of their residential part, emphasizing the diversity of architectural forms and their dimensions. The villa of Pardissous, built in the middle of the 1st century AD, offers a perfect example of these first small-scale farms. Its buildings (pars urbana/pars rustica) are organized around an open courtyard and its residential part, rectangular in plan, adopts a layout well known in Lyonnais Gaul, the one of the linear villa with integrated corner rooms and a front gallery. With an area of 230 m2, its pars urbana had one floor only. It remained in use until the second half of the 3rd century AD, after having undergone some slight modifications at the end of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Other villae have more elaborate plans (pi, central courtyard, or peristyle plans) and a variable, but generally larger footprint.

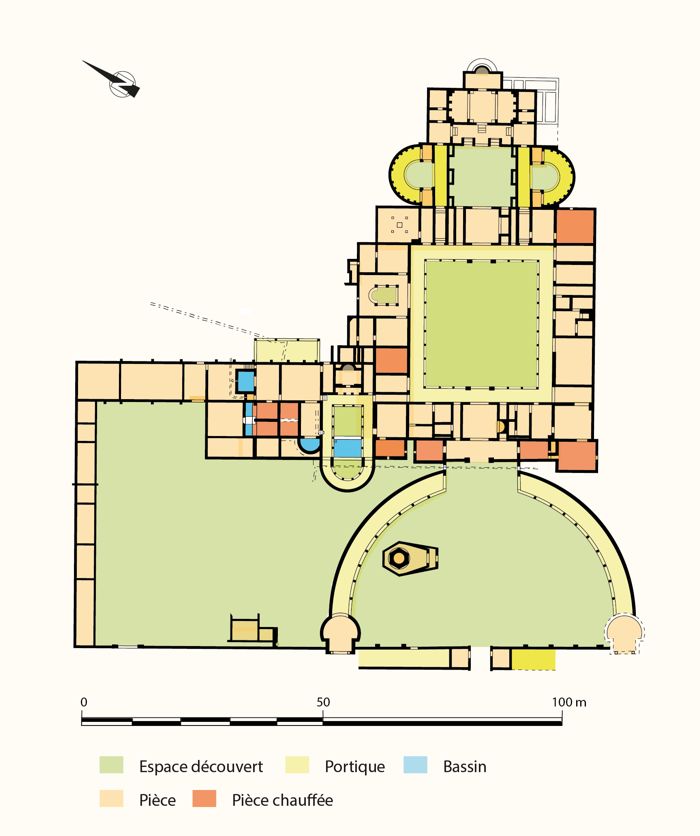

The thermal spaces sometimes reach important dimensions. This is the case in Séviac (Montréal-du-Gers), built in the 2nd century AD and 60 m away from the residential part. Thanks to its symmetrical plan, it contains all the rooms necessary for the thermal practice: entrance vestibule, apodyterium, frigidarium and quadrangular piscina, tepidarium, laconicum and caldarium. They were enlarged several times from the end of the 2nd century onwards and included two bathing sections. Some of the more modest villae were abandoned at the end of the 2nd century AD, and even in the 3rd century AD. On the other hand, were the subject of large-scale architectural programs during the 4th and 5th centuries AD. Those sumptuous residences, the property of the highest social class, sometimes are comparable to real palaces, often had several phases of work intended to enlarge them and embellish them with sumptuous decoration. Their plan is based on the principles of axiality and symmetry and they are often built around one or even two quadrangular courtyards with peristyle, with a large surface area (between 540 m2 and 2400 m2). This courtyard, often embellished with a garden that we imagine to be made up of green beds, planted with flowers and punctuated with sculptures, sometimes included a pool.

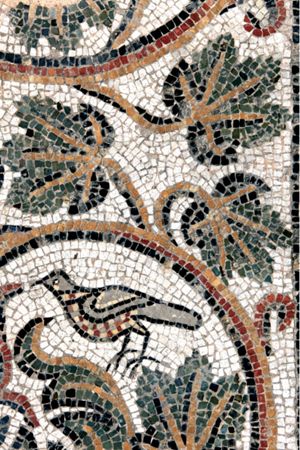

Other plans were also adopted. Thus, the elongated plan, preceded by a front gallery, of the villae of the High Empire is found, but in much larger dimensions. The partes urbanae, in rare cases, are organized according to a pi-shaped plan. At Saint-Martin (Aubiac), for example, differential maturation in wheat revealed three buildings opening onto a vast courtyard. In these villae, certain spaces have special arrangements and it is possible to determine their function. The vestibule must impress the visitor, and is sometimes distinguished by its shape or size, with the presence, in some cases, of two spaces generally in a central or quasi-central position on the façade of the house. The reception room(s), which generally open onto the peristyle, are also characterized by their original form (apse, triconch or cruciform rooms), by their size (between 80 m2 and 130 m2 or more), by the presence of a heating system when used in winter and by their mosaic paving. These houses are equipped with vast thermal complexes, which include the classic alternation of hot and cold rooms. Their singularity lies in the architectural forms adopted for some of the rooms (with cut-offs, poly-lobes, or horseshoe-shaped semi-circles). All these villae had sumptuous decorations: works of art, wall paintings, marble from the Pyrenees or from distant lands (Africa, Greece, Egypt) and mosaics. For the latter, polychrome mosaics, a wide range of materials was used, thus offering a very diverse palette. The most original compositions are composed of plant elements (laurel, acanthus, vines and fruit trees).

More modest rural settlements than the villae have been identified in the countryside and play an important role in their development. They are characterized by their simplicity of form, their small size, and lacking in comfort spaces, notably private baths, or reception rooms. They could correspond to small production units and some archaeologists call them “farms” for convenience. Others, even more modest, are probably huts for storing tools, or even temporary or seasonal dwellings linked to livestock farming.

The complete excavation carried out at La Pouche (Duran), revealed a rectangular building divided into two rooms of unequal size (75 m2). Built in the 40s and 50s AD, it seems to have been in use at least until the end of the 1st century AD. Its foundations (rough limestone blocks, bound with clayey silt and mortar), supported an elevation of small limestone rubble, bound with lime mortar, and the whole is covered with a tiled roof. Its floors are made of clay. The diversity of finds (sigillate and common ceramics, amphorae, glass, loom weights, chisels, pig and ox bones) suggests that the narrowest part of the building was used for housing, while the largest part was reserved for agricultural and craft activities. Aerial surveys have revealed numerous buildings that bear similarities to the few farms that have been excavated. Even if their precise function can only be ascertained by an excavation, their modesty, morphology, and the furniture collected suggest that they are small agricultural units. These constructions, generally isolated, have, in most cases, a rectangular plan, with, as at La Pouche, two spaces of unequal dimensions. The one at Garcin (Lamontjoie, fig. 5 and fig. 6), of about 170 m2, is preceded on the west by a gallery. Sometimes the plan is more elaborate, with two wings arranged perpendicularly and bordered by a gallery.

Surveys have brought to light a high density of occupation in certain city territories. For example, among the Nitiobroges (capital Agen), a systematic pedestrian survey carried out over 17 000 ha revealed some twenty ancient sites, including three villae, more than fifteen farms and possible huts. All these discoveries bear witness to open landscapes, likely to provide varied economic resources (cereals, wine, and livestock).

References

- Balmelle, C., 2001: Les demeures aristocratiques d’Aquitaine, Société et culture de l’Antiquité tardive dans le Sud-Ouest de la Gaule, Mémoires 5 / Aquitania Suppl. 10, Bordeaux.

- Bianchi, G., 2012: “Building, inhabiting and ‘perceiving’ private houses in early medieval Italy”, in: Arqueología de la Arquitectura, v. 9, p. 195-212.

- Bouet, A., 2015: La Gaule Aquitaine, Paris.

- Chabrié, C., 2016: “La villa de Pardissous à Massels (Lot-et-Garonne). Un exemple de petit établissement rural du milieu du Ier s. p.C.”, Aquitania, 32, p. 163-193.

- Conde, M., 2011: Construir, Habitar: A casa medieval, Braga.

- Pesez, J.-M., 1998: Archéologie du village et de la Maison rurale au Moye Âge, Lyon.

- Petit-Aupert, C., ed., 2018: Habiter en Aquitaine dans l’Antiquité, de la Tène finale à l’Antiquité tardive,catalogue d’exposition, Bordeaux.

- Pounds, N., 2005: The Medieval City, Westport/London.

- Réchin, F., dir., 2006: Nouveaux regards sur les villae d’Aquitaine : bâtiments de vie et d’exploitation, domaines et postérités médiévales, Actes de la Table ronde de Pau, 24-25 novembre 2000, Archéologie des Pyrénées occidentales et des Landes Hors série 2, Pau.

- Wickham, C., 2019: O Legado de Roma. Iluminando a idade das trevas, 400-1000, Campinas.