Contrary to the current – erroneous – idea of the Middle Ages as a period of illiteracy, writing was an extremely important and valued activity back then: for instance, the Evangelists, one of the pillars of Christianity, were often represented by the act of writing their respective Gospels. However, writing was then the work of experts. An author like Gregory the Great would not be called a writer, since he would not be the one writing down his vast work: he would dictate it to a professional writer, a scribe. Therefore, in the Middle Ages to be a writer was not synonymous with being an author, as it could be the case today. Writing was not only a knowledge acquired in parallel with reading but also a technique. After all, one must remember that there was no such a thing as mechanical reproduction of texts, there was only the manual form of it, which required long-term learning and training in order to satisfy this demand. Thus, any medieval book can be called a manuscript – a book written (scriptus) by hand (manu) –, although this modern word which dated from the late 16th century, would not make sense in the Middle Ages due to its obviousness.

Books were then, the main product of writing. Even loose writings such as letters or donation documents, for example, could be assembled in books. That could be called libri (sing. liber) or – after the preferred format since around the 4th century – codices (sing. codex). Those books are still preserved by thousands today, although this number is no comparable to the former which have been lost throughout history.

To produce a manuscript

The production of a book involved many operations and writing was just one of them, if not the most important one. Before writing the text, it was necessary to prepare the support that would receive the writing, the instruments with which it would be written and the ink. If it had images, it could be made after the text. Only then, the book would be considered finished. This entire process, which required specific knowledge and technique, is well known by scholars as it has been described by textual and iconographic sources.

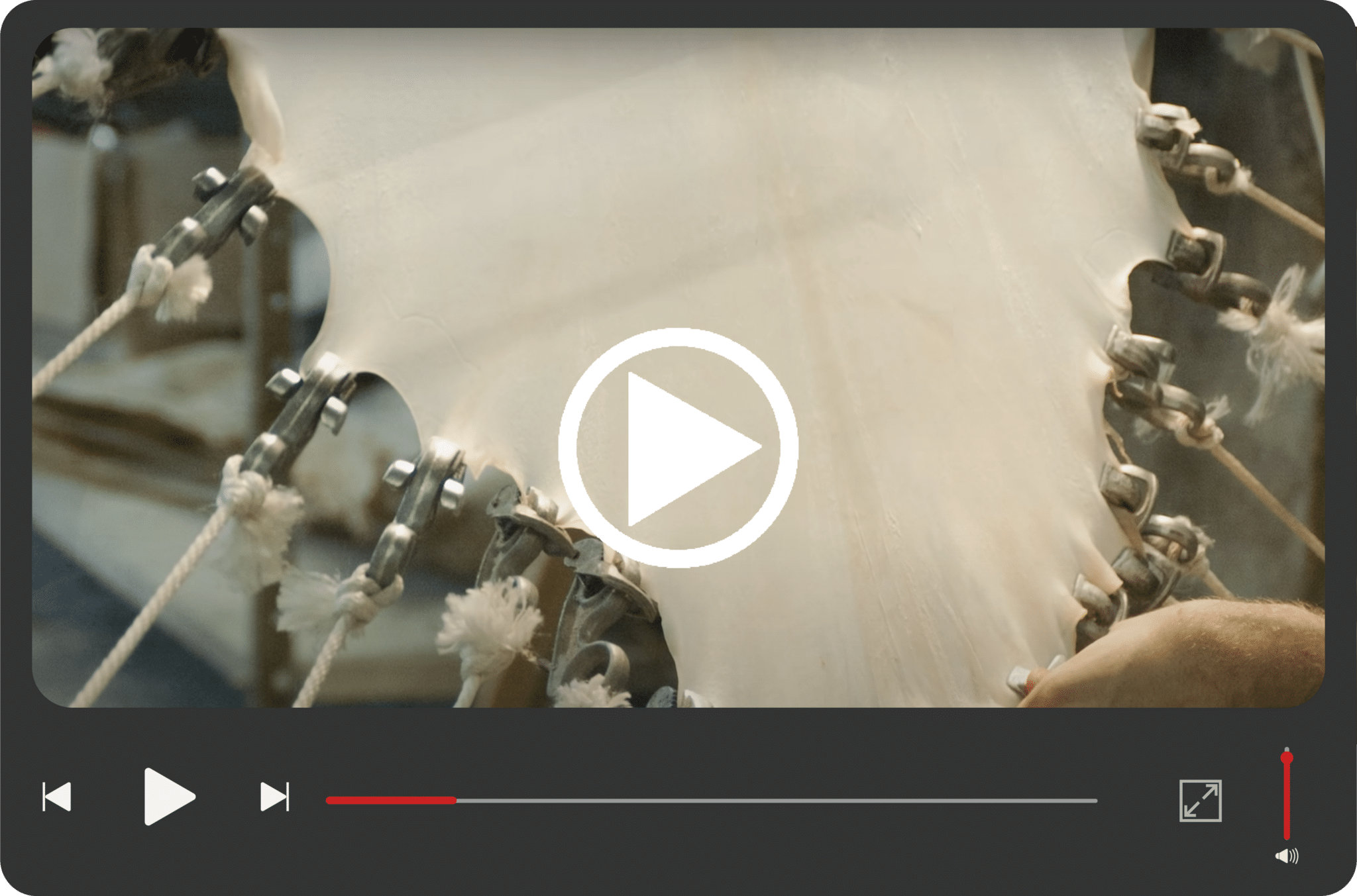

Then, the first step was to produce kinds of support for writing: since the 4th century it has mainly been the parchment, that is, the skin of an animal (calf, sheep, goat). There was a whole series of procedures, which lasted for days, the skin must be extracted, the fur to be shaved, the fat to be eliminated and the skin to be stretched. Afterwards, the parchment would be cut according to the desired size.

Another stage was the preparation of the black writing ink, usually an iron-gall ink made from oak-gall, the excrescences produced on an oak tree by the eggs laid by a gall wasp. Another important color for writing was red used to do the rubric, that is, to highlight important parts of the text, such as the beginning of a chapter or a book (what we call incipit). The red pigment was usually red lead, an oxide of lead, called minium in Latin, whence miniature, a common way of calling the images of a manuscript (initially outlined in red). To paint the images, other pigments were needed, and each one was produced separately from a certain raw material (for example, roots, leaves, insects, etc.), mixed with water and some binding agent (egg, salt, egg yolks, urine, etc.). When used, all the inks and paints were placed in horns, shells, or leather containers, where the copyist or the painted dipped their instruments.

A third important preparatory stage was to prepare these instruments for writing and painting. The writing was done with a calamus (piece of reed) or with a quill (usually goose), both hollowed out so the ink could be drained. As for the brush, it was made with animal fur and was very similar to our hair. Another important tool was the penknife, which served to hold the parchment in the pulpit, to make the point on the quill and to scrape the parchment in case of error (other forms of correction were to scratch the word or underline it).

The book was planned in advance: the ruling was done by means of pressure exerted on the skin in a dry point (such as the handle of the penknife, for example) or by means of plummet (or lead point), from the 11th onwards (and colored ink in the late Middle Ages). The space for text, margin, ornament initials and/or images, only if it was planned. The sheets of parchment, called folios, were written separately. Only after the whole set (text and images) was ready and revised would the book be sewn to form the codex, with folios grouped by quires, in a process not unlike what can still be done with paper books today. If it was a very luxurious book, it could be given, besides its usual damp leather covering, an applied cover made of ivory or other precious material set onto the board of the biding.

A valuable object?

It is important to mention that books were objects of great material and symbolic value: since they demanded a high cost of execution (for example, an animal skin made only four folios in general), they could demonstrate the high status of its owner, being mentioned among the goods bequeathed in testament or presented to kings, for example, besides being a constant attribute in the images of Christ in majesty.

Regarding the writing itself, it was done in general by people trained in the art of calligraphy, aiming for regularity and uniformity of the ductus, especially from the 8th century onwards. Often more than one scribe worked on the same work, thus reducing production time – but in such cases, the transition from one hand to the other should be as unnoticeable as possible. There can be seen, however, some important differences when looking at large sets. After all, according to the time and place, writing had variations, constituting distinct script styles, responding to diverse needs, from the desire to create an identity for a group of scriptoria to the need for greater clarity and speed, as it was the case of the Carolingian minuscule or Caroline, developed, as the name indicates, in the 8th century Frankish world.

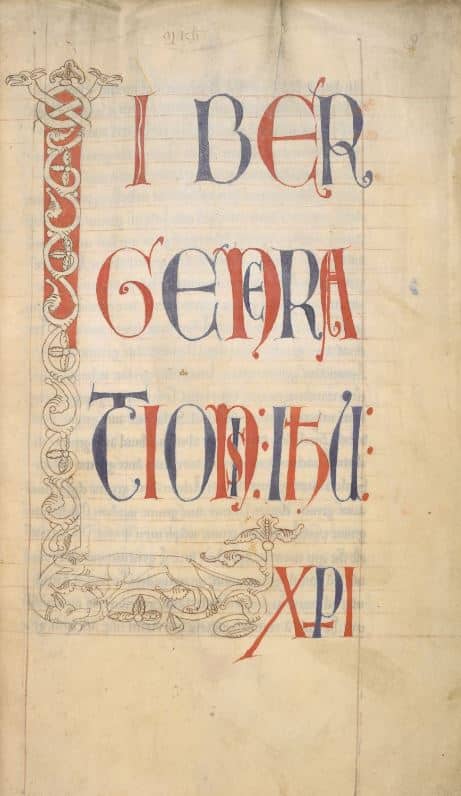

When writing, abbreviations were often used, which were more or less encoded, and some kinds of punctuation. There might also be some kind of distinction between uppercase and lowercase letters. The letters that started a sentence, a chapter, a book – which we call initials – generally stood out from the others in some way: the larger size, the use of another color or even because it was ornamented with images.

The scenario in which this work took place was mostly, until around the 12th century, a monastic scriptorium and, after that, an urban atelier. Consequently, the scribes would be mainly monks, in the first case, and lay people, in the second – and they would not only be men, but also women, both nuns and lay people. Learning to write was generally done from a young age, whether in the scriptorium of a monastery or in an atelier (which was often family-owned).

The work of writing was much valued, especially in the monastic context. We find praise for such activities, for example, in the work of Cassiodoro, Institutiones (I, 30, 1) “Joyful is [the scribe’s] intention, praiseworthy his zeal: preaching to men only with his hands, opening tongues with his fingers, silently giving salvation to mortals, and fighting against the devil’s illicit temptations only with calamus and ink”. At the same time, complaints on the margins and colophons of manuscripts are not uncommon, such as the scribe Florentius de Valeranica who described at the conclusion of a 10th century copy of the Moralia in Iob (Madrid, BN Mss / 80, fol. 500v) the scribe’s plight:

The scribe’s work is the reader’s refreshment: while the former weakens the body, the latter enriches the mind. Whoever you may be, you who profit this work, do not forget the worker who made it, so that God, thus invoked, will forgive your sins. Amen. Since one who does not know how to write thinks that it is not a labor, I will describe it for you, if you want to know how hard the work of writing is. It mists the eyes, bends the back, breaks the stomach and ribs, it fills the kidneys with pain and the body with all kinds of suffering. So, turn the pages slowly, reader, and keep your fingers away from the pages, because just as the hailstorm ruins the fertility of the soil, a sloppy reader destroys both the book and the writing. Just as the last port is sweet for the sailor, so is the last line for the scribe. Explicit, thank God.

Read more

Primary works

- Cassiodoro, Institutiones, Florentius de Valeranica, Moralia in Iob, Madrid, BN Mss / 80, fol. 500v.

References

- Agati, M.L., 2003: Il libro manoscritto. Introduzione alla codicologia, Roma.

- Alexander, J. J. G., 1992: Medieval Illuminators and Their Methods of Work, New Haven.

- Brown, M. P., 1994: Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts: A Guide to Technical Terms, Malibu/London.

- Clemens, R. & Graham, T., 2007: Introduction to Manuscript Studies, Ithaca/Londres.

- Coulson, F. T. & Babcock, R. G., (eds), 2020: The Oxford Handbook of Latin Palaeography (2020; online edn, Oxford Academic, 10 Nov. 2020), URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195336948.001.0001.

- Géhin, P., (dir), 2017: Lire le manuscrit médiéval: observer et décrire, Paris.

- Jakobi Mirwald, C., 2014: Buchmalerei. Terminologie in der Kunstgeschichte, 4. ed. rev. ampl. Berlin.

- Maniaci, M., 1996: Terminologia del libro manoscritto, Roma.