Fighting and warfare narratives fulfil the annals of sovereigns in the world history. Sometimes these narratives are accompanied by images, celebrating the battle achievements. Thus, the warfare condition has established itself not only during its own emergence as war, but as an expression of the pragmatics of the military organization, as we have seen above. Additionally, it is represented in war memorials, or onto objects with sculpted or painted battle scenes. These examples give colour to the emblematic phrase: war is too serious to be left to military forces. War representations found on non-textual materials can reflect their importance outside the military dimension. Therefore, besides an art of war, in the sense of how to make war, we can also address the war in the arts.

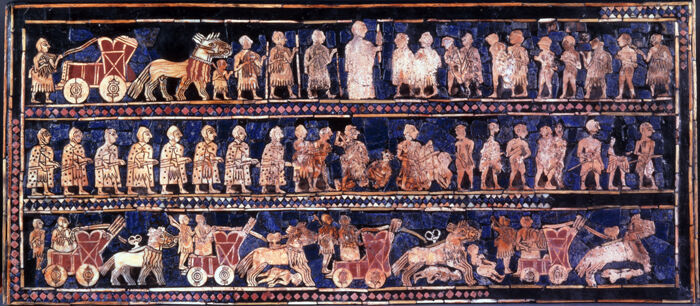

The war expressed in material culture sources can be considered impressions of war, i.e., the way the war is remembered or fostered. For ancient societies, some objects are worldwide recognized by their war scenes: The Standard of Ur, from the 3rd millennium Mesopotamia; the “Achilles Shield”, from the Mycenaean period; the Trajan Column, still exposed in Rome. Besides the common inquisitive historical questions, further enquiries can be directed to the material aspects of these objects: Were they accessible to be touched and/or seen? Were they made from a culturally relevant source material? What were their uses in this context?

Among the occurrences of fighting and war in the ancient material culture, the palace wall reliefs of ancient Assyria, from the 9th-7th centuries BCE in Mesopotamia, are exemplary sources for a historical analysis and are a representative case to answer these questions. These sculpted stone slabs contain representations of the Assyrian kings and battle scenes, as well as hunting and construction scenes, processions of booty and prisoners, and symbolic figures used to repel demons. All these figurative elements are arranged to foster in most slabs a sequence of scenes, forming a visual narrative.1

One way to approach them – which can be adapted to other representations of war in the material culture – is to address an observational survey, without discounting the historical context in which a set of reliefs was produced. As for war scenes, which is a prominent motif in the palace reliefs, they are based in historical events, even though they always emphasize the Assyrian victorious view. In addition to this confluence between the real and the depicted, figurative details were employed to highlight the historicity of the scenes, e.g. topographical and architectural elements, body aspects, and weapons.

The relief iconography of war can be divided in three sequential scenes: the preparation to the battle, involving the Assyrian soldiers marching toward a city; the fighting itself, and the final procession of booty and prisoners (see the insert). Also, we see glimpses of punishments, bodies falling or laying on the ground, or heads being carried or in piles. Therefore, war (and violence) is intentionally represented, and this is striking evidence which opens the opportunity to examine the meaning of this source in its own context. For example, they aid us to infer on how the Assyrians have seen themselves and how this view was shaped by the way they have seen (and treated) the others.

These fighting scenes have served as evidence of the Assyrian way of war. In parallel with royal inscriptions (some of them inscribed in the same slabs), we see the siege strategy as a tactical trend, consisting in dividing the army to invest on the corners of the cities.2 Additionally, the brutality of the Assyrian policy is summed up by the common consideration of the reliefs as an official war propaganda. Alternatively, one can pose the questions: Where and how can the reliefs be seen? And who can see them? Indeed, the reliefs with war scenes are displayed throughout the palace walls, but the restrictedness of the rooms makes us rethink about propaganda. Although the scenes express the royal ideology, “propaganda” is a misunderstanding, considering the visibility conditions of the reliefs.3 The war was an important ingredient for the Assyrian empire, but there is a risk to unwarily overstate the war as a main motivation of their policy.4

©The Trustees of the British Museum (BM 121201). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Conversely, the reliefs as art of war (or the war in art) aid to sustain and to foster the fighting predisposition. They repeatedly remember the palace members on the Assyrian mission, which was given by their main god, Assur.5 Thus, maintaining the “war mood” represents a role of the war in the social sphere beside the war event itself.

The Assyrian palace reliefs form an exemplar case which highlights aspects of the ancient fighting and warfare and inspires the study of other war representations in material culture. It has been fruitful to think on the themes, positions, and the visibility of these images. Considering the place and role of objects related to war in the ancient societies, we rethink on the seriousness of the war to be left only on the military hands. It could be interesting, as the ancient people show us, to leave the war on the artists’ hands too.

References

- Bachelot, L., 1991: La fonction politique des reliefs néo-assyriens”, in: Charpin, D. & Joannès, F. (org.), Marchands, diplomates et empereurs. Études sur la civilisation mésopotamienne offerts à Paul Garelli, p. 109-127.

- Bagg, A., 2016: “Where is the public? A new look at the brutality scenes in Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions and art”, in: Battini, L. (org.), Making Pictures of War. Realia et Imaginaria in the Iconology of the Ancient Near East, Oxford, p. 57-82.

- Nadali, D., 2019: “Images of Assyrian Sieges: What They Show, What We Know, What Can We Say”, in: Armstrong, J. & Trundle, M. (ed.), Brill’s Companion to Sieges in the Ancient Mediterranean, Leiden/Boston, p. 53-68.

- Rede, M., 2018: “The image of violence and the violence of the image: War and ritual in Assyria (Ninth-Seventh centuries BCE)”, Varia Historia, 34, n. 64, p. 591-623.

- Winter, I., 1981: “Royal Rhetoric and the Development of Historical Narrative in Neo-Assyrian Reliefs”, Studies in visual communication, 7, p. 2-38.