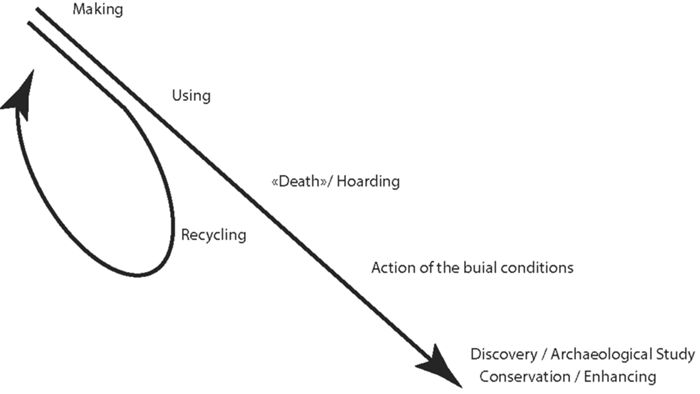

The archeological approach is based on productions of various kinds, which have been established at some moment in the past, and which have evolved up to their aspects at the excavation time. Therefore, we must analyze the elements, from movable objects to ruins, which are part of diverse and complementary dynamics. From shaping, to the use until the abandonment then degradation. In order to do it, we need to reconstruct all the phases in the life of the vestiges.

The material’s shape is the first – and probably the best known – phase that consists on transforming materials to produce the desired item. This phase requires a selection of materials that must fit the desired result, and the conception of the item to be produced. To produce the object, one must follow several steps involved in the what-so-called “chaîne opératoire” named by André Leroi-Gourhan.1 The “chaîne opératoire” diversify according to the materials and the goals, it would also be too long and brief to summarize all of them here.

Therefore, the shaping phase is the first moment when we can distinguish a human intention, a will to produce. At the same time, we can also mention the wastes that occur during this phase and which are of major interest for the understanding of the techniques that were used.Using corresponds to the phase when the item produced is deployed in the way which it was designed for. It testifies to specific or occasional needs for which productions have been diverted from their main use. Those adaptations for new function are frequent and affect all types of production, from buildings to jewelry. This phase of reuse can be associated with a modification of its initial form, that is why it is important to take a detailed look when it comes to analyze it in order to mentally restore the initial form and understand the purpose for which the object was created. One must emphasize the case of recycling, which is more or less important depending on the materials used and their capacity to be recycled. Indeed, if an item is reused, it goes through a complete phase where the “chaîne opératoire” erases all marks of its first form. The former item has then become raw material in order to produce something else (this is often the case for fusible metals).

To abandon is a decisive moment in the archaeological analysis of past societies. Abandoning an object or a habitat indicates a desire to change something, to modify one’s relationship with the environment. This can be associated with technical constraints (breakage), social constraints (obsolescence) or ritual constraints (offering). The context of abandonment is the archaeologist’s first source: it is because a building has been abandoned or an object deposited that they can be found during excavation. Therefore, this abandonment phase is the first to be operated by archaeologists, using stratigraphical data. The study of the context allows us to understand the conditions of burial both analysis of the vestiges and for the understanding of the past societies. Depending on the environment, items are preserved in different ways, and it is therefore necessary to control these parameters to include them in the Material Culture vestiges’ analysis.

The analysis of the different phases of the item’s life allows us to a better understanding of each phase of it. In this way, we can take each of its moments fully into consideration. The moment that has attracted the most attention from archaeologists is the shaping one. As we explained, shaping is the transformation of material to produce an element that responds to a concept. By observing the similarities and diversity of objects, one can group them into types and establish a typology. The study of these types across different sites has made it possible since the end of the 19th century to define areas in which human groups interacted and adopted similar concepts.2 Consequently, it was possible to associate certain types of items which societies defined in time and space. By cross-referencing this information with stratigraphic contexts and applying the typological method to a large corpus, it becomes possible to set up typochronologies very useful in archaeology

References

- Boas, F. (1888): The Central Eskimo, Washington.

- Leroi-Gourhan, A. (1964): Le geste et la parole, Paris.

- Tylor, E.B. (1871): Primitive Culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art and custom, London.