The city and its relationship with the countryside is undoubtedly the process that most often characterises Mediterranean Antiquity. This relates to Phoenician and Punic ports (both eastern and western), Etruscan centres, Greek poleis and Roman civitates as well as Iberian and Celtic fortresses and oppida.

The element common and behind this urbanism process, above all economic, is ‘non-self-subsistence’ which translates into the way of supplying food – and more broadly, its consumption – to and by the inhabitants of centres above and beyond exclusively local agro-pastoral activities. It in fact relies on commercial exchanges and is subsequently linked to the emergence of craftwork. Paradoxically, this transition from ‘rural’ to ‘urban’ economic models led to an intensification of agricultural production or, at least, of one type of production (cereal cultivation) that guaranteed the supply of the group and/or provided the source of trade.

This boom in agricultural production and trade development was a fundamental step in the process of urbanisation as it reflects the existence of a diverse urban network combining classical civilisations and indigenous communities and its introduction into the Mediterranean commercial circuit marked by dual rapports, that is, city-countryside and indigenous-classical worlds.

In this context it was certainly the urban commercial demand that provoked the development of the cultivation of cereals and was behind the organisation of the exchange network that integrated the different communities belonging to the same or different ethnic groups.

Moreover, it is commonly accepted that labour specialisation is the stage in all societies that follows significant agricultural development. The increase in agricultural production frees part of the workforce that is essential to urban growth whether for para-agricultural productions – metal and ceramic crafts in particular – or for activities linked to services such as the organisation of trade. The latter formed an integral part of the city and, more importantly, implied the presence of a merchant class specialised in procuring and redistributing food, with a body of specialists devoted to storage, transport, transformation of food resources and accounting.

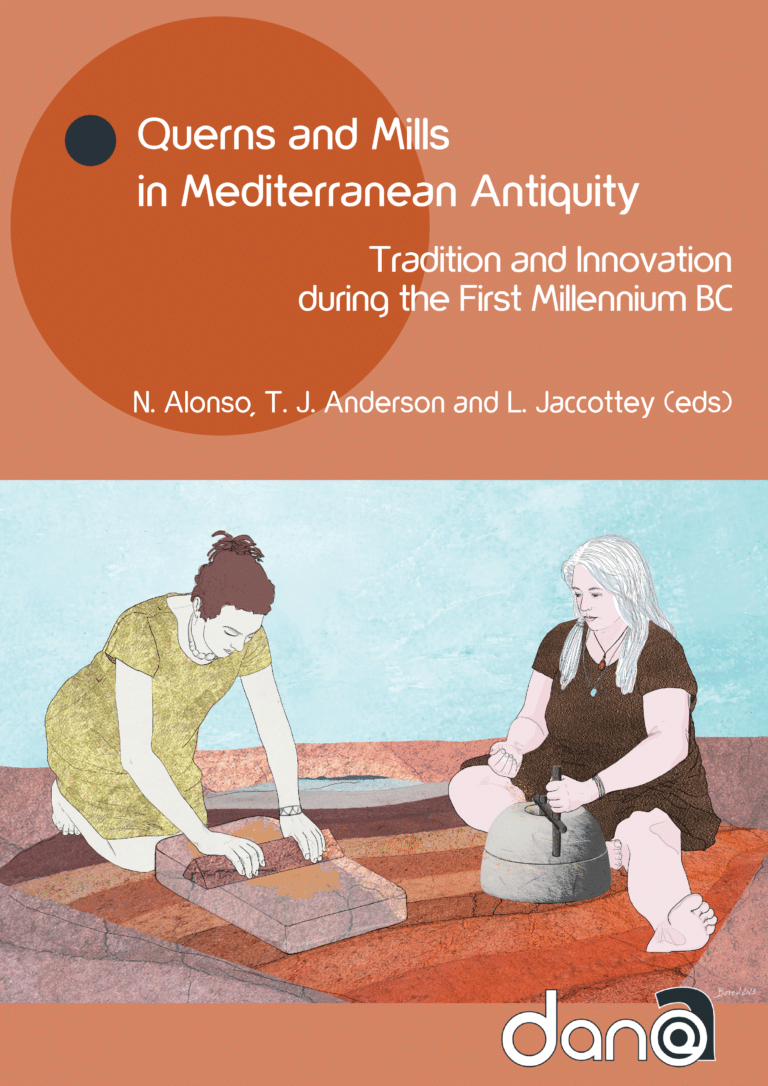

One must most likely place the analyses of grinding tools, their development, their improvement, their transformation and their distribution within this framework. Indeed, without denying the technical importance and typological diversity of Neolithic querns, the 1st millennium BC saw the development of the urban phenomenon, demographic growth and the intensification of cereal cultivation that led to significant innovations affecting the means of grinding and therefore the methods of production of these tools boosting their yield. Regional types gradually spread and replaced traditional tools (essentially the to-and-fro querns).

This study thus comprises contributions from prehistorians, classical archaeologists and historians of techniques. Allow me here to pay homage to my colleague from Aix-en-Provence, Marie-Claire Amouretti (1935-2010), who throughout her work and research inspired, and recognised the need, always with a keen interest and a spirit of openness, of bringing together researchers from different backgrounds to delve into this important subject. It is thanks to this approach and the development of archaeological excavations that it has been possible to cross material culture and palaeoenvironment data, leading to great progress in research. Ethnoarchaeology, scientific meetings, academic work and specialised publications, field discoveries, typological and technical studies, experimental archaeology have in fact multiplied throughout the last a generation. Natàlia Alonso, T. J. Anderson and Luc Jaccottey, the editors of this book, are among the best European specialists on the subject. They have brought together a number of colleagues who from Israel to Iberia and Gaul to Greece have contributed and enriched the debate on the use of ‘querns, millstones and mills’ in ancient Mediterranean. While reading these proceedings we will discover the origin of the raw materials serving for grinding – and at times the querns and millstone themselves. These are essential questions in the articles by Sophie Duchène for Attica and David Eitam for Israel. Querns and millstone typology is the subject of regional analyses both in Israel (Aaron Greener et al.) and Olbia – a Greek enclave along the coast of Provence (Luc Jaccottey and Sylvie Cousseran-Néré). Southern Gaul and especially the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula (Catalonia and the Valencian region) are privileged areas of study which, respectively, benefit from the expertise of Luc Jaccottey, Natàlia Alonso, Jaime Vives-Ferrándiz and their collaborators. A wide international dissemination of their research is essential, and this book in English undoubtedly serves this purpose.

These proceedings thus further bolster the notion that querns and millstones were not trivial tools but stemmed from social, economic and fundamental technical evolutions affecting the ancient societies of the Mediterranean.