Introduction

The oldest rotary mills in the Mediterranean and Europe which have been widely published (e.g., Alonso 1999, 2015; Alonso & Frankel 2017) are recorded in the middle of the 1st millennium BC in the framework of the dawn of the Iberian Civilisation (Early Iberian period) throughout the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula to the south of France.

Two types stand out: the rotary quern and the Iberian rotary pushing mill. The first consists of two circular stones ranging from 25-50 cm in diameter and not exceeding 25 cm in height (Alonso & Pérez-Jordà 2014). In spite of several typological classifications, none appears to cover the entire Iberian world or serves to define clear regional differences (Anderson 2016; Py 1992; Équipe Alorda Park 2002; Longepierre 2012, 2014). Current ethnographic examples reveal that the smaller rotary querns were generally operated at ground level by a person with one leg bent and the other stretched out. There are also examples of these smaller models on elevated features attached to walls, a system offering more comfort and yielding a greater quantity of flour in less time (Alonso 2019). The second type is the larger pushing mill, exceeding 50 cm in diameter and only recorded at sites of the Iberian Culture. Its driving system from a standing position is new and inferred from its diameter (too large to be operated by hand), massive weight, and position often set on elevated podiums (Alonso et al. 2016).

The earliest rotary querns and pushing mills are recorded at Iberian Culture sites in Catalonia and the Aude in France: Fortress of Els Vilars (Arbeca, Lleida), Turó de Ca n’Oliver (Cerdanyola del Vallès, Barcelona), Ciutadella de Calafell (Calafell, Barcelona) and Pech Maho (Sigean, Aude) (Alonso 1999; Équipe Alorda Park 2002; Longepierre 2012, 2014). These models swiftly spread in the 5th-4th centuries BC throughout the east of Iberia and the south of France to the Rhone Valley (Alonso & Pérez-Jordà 2014; Longepierre 2012) and in the 3rd-2nd centuries BC throughout all of Iberia (Alonso 2014), the north and south of France up to the Rhone (Jaccottey et al. 2011) and beyond the Alps to Central Europe (Wefers 2011). Rotary mills in Provence, however, did not become widespread until the last quarter of the 2nd and the end of the 1st century BC (Jaccottey et al. 2011).

However, the evidence clearly reveals that the early rotary mills were always accompanied throughout the Iron Age by hand querns (also known as saddle querns) driven with a to and fro motion until finally they fell generally into disuse towards the end of the Iron Age. In the initial moments and throughout the centuries immediately prior to the widespread adoption of the rotary movement, to and fro querns in fact underwent a series of modifications, mainly morphological, not only in the NE of Iberia but also throughout the rest of the Mediterranean (Alonso & Frankel 2017).

The current study thus focuses precisely on this moment immediately prior and contemporary to the introduction of the rotary movement in the NE of Iberia (between the 8th and 5th centuries BC) without delving into the situation of milling of the Middle Iberian period (from the 4th century BC onwards). This analysis is primarily centred on two key sites, notably the inland Fortress of Els Vilars (Arbeca, Les Garrigues, Lleida) and the coastal settlement of Turó de la Font de la Canya (Avinyonet del Penedès, Alt Penedès, Barcelona) (Fig. 1). Each reveal different dynamics, especially with respect to the introduction of the rotary mill (which took place earlier at Els Vilars) and contacts with other Mediterranean populations, more prevalent at Font de la Canya.

5. Penya del Moro (Sant Just Desvern, Baix Llobregat); 6. Ciutadella de Calafell (Calafell, Baix Penedés); 7. Barranc de Gàfols (Ginestar, Ribera d’Ebre); 8. Tossal del Moro (Pinyeres, Batea);

9. Sant Cristòfol and Les Escudines Altes (Massalió, Matarranya); 10. Taratrato (Alcanyís, Baix Aragó); 11. Moleta del Remei (Alcanar, Montsià).

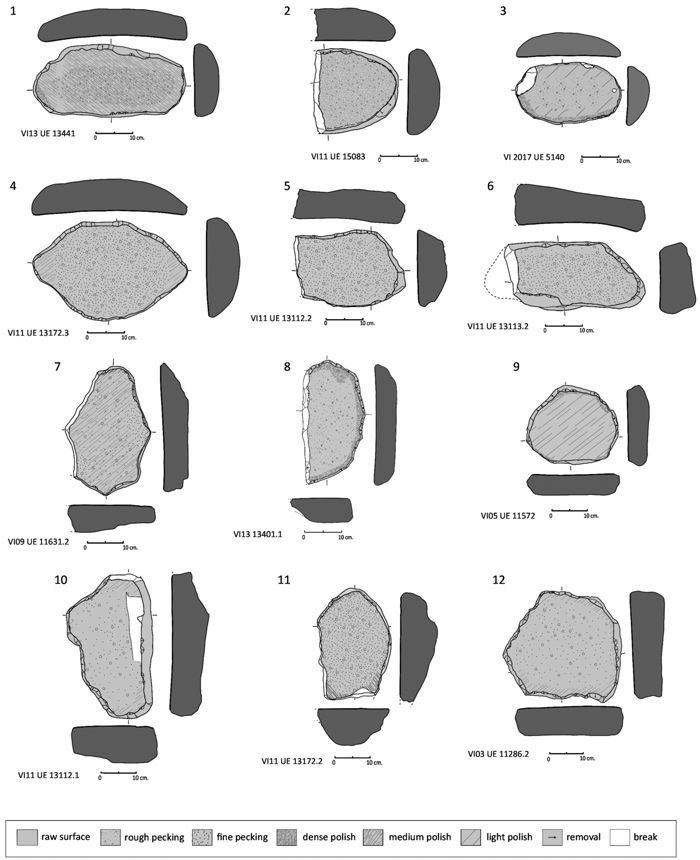

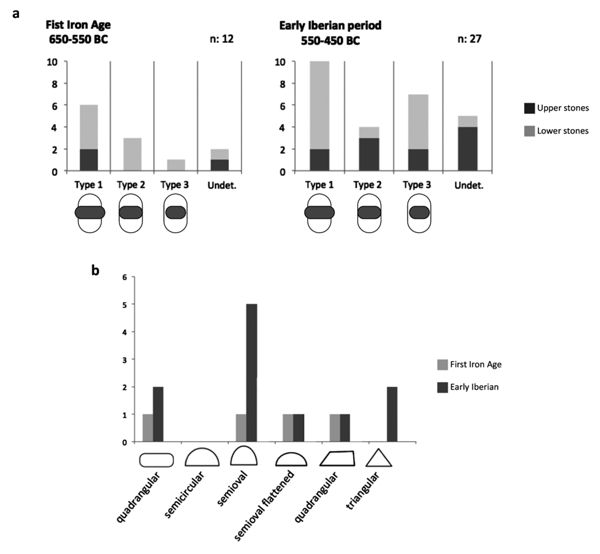

The current analysis primarily bases itself on three types of to and fro querns from the two sites characterised by the correlation between their upper (active) and lower (passive) stones (Zimmermann 1988). Other morphological aspects (which will be explained later) were likewise considered, notably the shape of the lower stone and the section of the upper stone. This analysis stems from three quern types which categorised based on the characteristics of their upper stone and on the traces of use-wear observed along the transversal and longitudinal sections of both their upper and lower stones (Fig. 2):

- Type 1, overlapping upper stone: the length of the upper stone surpasses the transversal width of the lower stone. This enables the operator to grasp the upper stone by its ends. The wear on these upper stones yields a concave longitudinal section (visible when its ends are preserved) and a flat-convex transversal section. Use of the lower stone also yields a concave longitudinal section and a flat or convex transversal section.

- Type 2, covering upper stone: the length of the upper stone is equal to the width of the lower stone. Hence the individual operating this quern grasps or leans on the active upper stone from above. The use-wear on the upper stone is regular yielding a flat longitudinal section and a flat or slightly convex transversal section. Conversely, the lower stone of this type reveals a flat transversal section, whereas the longitudinal section is either flat or slightly concave.

- Type 3, short upper stone: the length of the upper stone is less than the width of the lower stone. The individual operating this quern grasps or leans on the upper stone from its top, most often through contact with its central apex. In these cases, both the longitudinal and transversal sections of the upper stone are convex and those of the lower stone concave.

One must nonetheless take into account that it is often arduous to differentiate between the passive and active stones, especially between Types 1 and 2. Each in the first case reveals similar profiles, notably concave active surfaces in the longitudinal sense and flat-convex active surfaces in the transversal sense. In the second case, in turn, all the grinding surfaces can be flat (Fig. 2). Therefore, the percentages between one and the other presented below must be interpreted with caution. Despite this difficulty, what follows is description of the general characteristics of the different mills. The focus is nonetheless on presenting more detailed aspects of each of the to and fro quern types from the First Iron Age and the Early Iberian period.

The to and fro querns

of the Fortress of Els Vilars (775-450 BC)

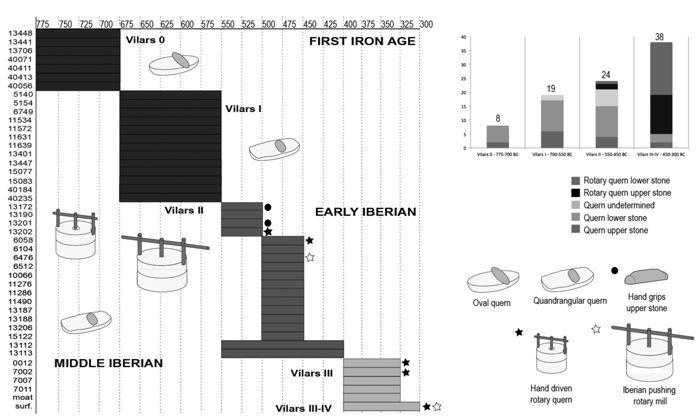

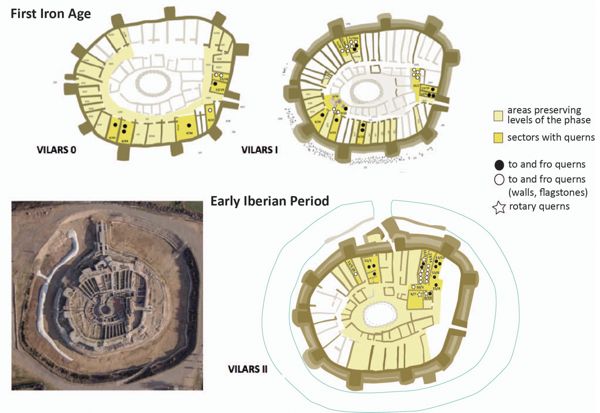

The Fortress of Els Vilars d’Arbeca is located on the Western Catalan Plain near the city of Lleida (Fig. 1). It has benefitted from a scientific and heritage project piloted by the University of Lleida since the end of the 1980s revealing the site’s great contribution to Iron Age research. The findings, on the one hand, have shed light on the historic evolution of Catalonia, in particular its Western Plain, as the fortress manifests a clear model of the socioeconomic transformations which took place during the Iron Age. On the other hand, its defensive system embodies an unusual phenomenon in the region as the fortress is geographically isolated from other similar features both in the Iberian Peninsula and in Europe. At its founding it occupied a surface of approximately 8000 m2 and was surrounded by an impressive defensive rampart reinforced by 11 towers encircled beyond its walls by a standing stones (chevaux-de-frise) and a moat 13 to 20 m in width. The defences enclosed an area (2 000 m2) three times as large as its domestic space (Junyent-López 2016; López et al. 2020; Alonso et al. 2020) (Fig. 4). Its foundation, occupation and abandonment took place during the First Iron Age and the Iberian period. The chronology of its lifespan is as follows:

- First Iron Age

Vilars 0: 775-700 BC

Vilars I: 700-550 BC

- Iberian period

Vilars II: 550-450 BC (Early Iberian)

Vilars IIa subphase: 550-500 BC

Vilars IIb subphase: 500-475/450 BC

Vilars IIc subphase : 475/450-425 BC

Vilars III: 425-325 BC (Middle Iberian)

Vilars IV: 325-300 BC (Middle Iberian)

The mills of the Fortress of Els Vilars

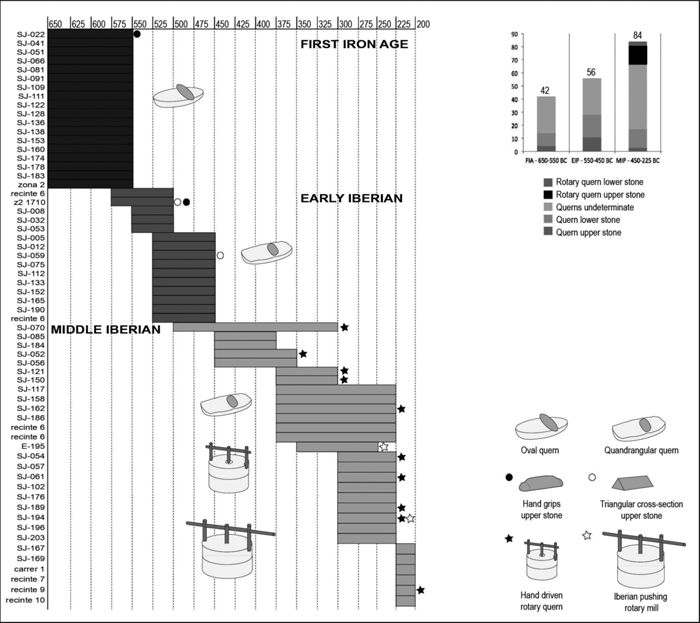

A total of 89 whole and fragmented mills were recovered from all of the different phases of occupation of the site thus shedding light on their evolution over the course of five centuries (Fig. 3). Unfortunately, very few were discovered in situ, that is, where they were used or stored. Most were recycled as construction material in the walls of buildings, in the pavings of houses or streets, or in the facings of the scarp of the moat. Their datings therefore correspond to their reuse. In any case, none of their datings are relevant to the introduction of new mill types or to other remarkable molinological characteristics.

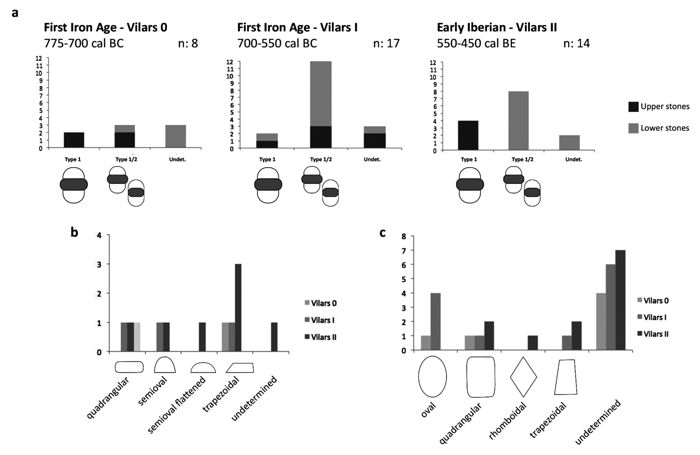

A total of 27 mills, all to and fro querns, come from the initial First Iron Age phases (Vilars 0 and Vilars I) (Fig. 3). This assemblage is broken down into 63% lower stones and 30% upper (7% undetermined). The subsequent First Iberian phase (Vilars II) of the Early Iberian yielded a proportion of to and fro querns representing 88% of the total. This phase also includes three rotary mills (a rotary quern lower stone, SU 6058, and upper stone SU13201; and an upper stone of an Iberian pushing type, SU 6476). These are among the oldest rotary models as SU13201 dates to the second half of the 6th century BC (Vilars subphase IIa) while the other two (SU 6058 and SU 6476) to the outset of the 5th century BC (Vilars subphase IIb). Among the to and fro querns, 19% are upper and 52% lower stones while 29% remain undetermined.

The finds in the Fortress of Els Vilars from the Middle Iberian period (4th century BC) clearly indicate an interchange of proportions as the percentage of to and fro querns decreases to 13% while that of the rotary type increases to 87%. However, although this numerical substitution is highly plausible, it is necessary to take into account the site’s post-depositional evolution. Els Vilars is a tell, a type of settlement prone to destruction by agricultural work. In fact only a few Middle Iberian dwellings, the logical spaces to recover mills, were spared from destruction in the 1970s (López et al. 2020). In fact, most of the information as to rotary mills comes from the well-preserved fills of both a central cistern and the moat. Each contained a considerable number of fragments, at times roughouts in the process of manufacture, either in their fill or reused on the walls of the scarp of the moat (Alonso et al. 2011). Hence, the previous percentages must be considered with caution. In any case, the to and fro querns in these levels, as noted, are very scarce, consisting notably of two upper and three lower stones.

As noted, the find spots of these mills within the settlement correspond to secondary positions. This notion is likewise bolstered by their very irregular distribution, with concentrations linked to reuse in construction. Examples are the groupings in zones 11 and 15 of the Vilars I phase or in sectors 3 and 14 of zone 13 of the Vilars II phase (Fig. 4). Even so, the 100% concentration of all mill types (to and fro and rotary) dating from the Early Iberian (Vilars II) to the north of the fortress suggests specific spaces dedicated to the transformation of cereals or other foods. Yet once again, it is necessary to take into account the differential conservation of structures from one phase to another. The levels of this phase to the east and west were either not or very poorly preserved, contrasting with those between the southern and northern areas.

of the Early Iberian period.

Evolution of the to and fro querns at Els Vilars between

the First Iron Age and the Early Iberian period (8th to 5th century BC)

Thirty-nine to and fro querns among the total of 48 complete and the fragmented cases recovered in the first three phases of the site could be classified as either upper or lower stones. Of this lot, 31 of the better preserved examples fall into the two types described in the introductory section (Fig. 2). Eight were identified as the overlapping Type 1, while the others are either of this type or of Type 2 (covering upper stone) (Fig. 5a). In many cases it is difficult to discern between types leaving many either undetermined or, as noted, between one type or the other. As the number of samples per period is very small, the results must be considered as merely indicative.

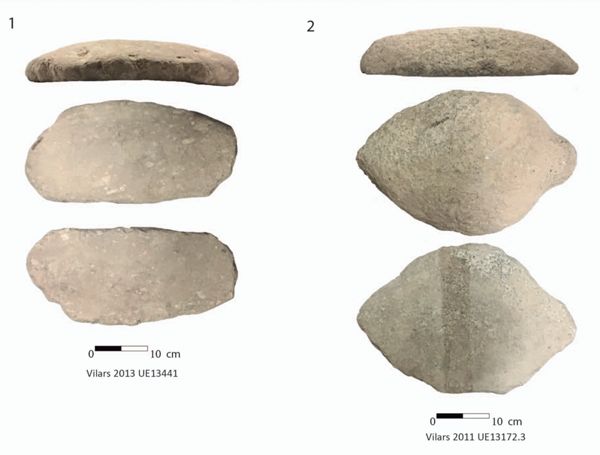

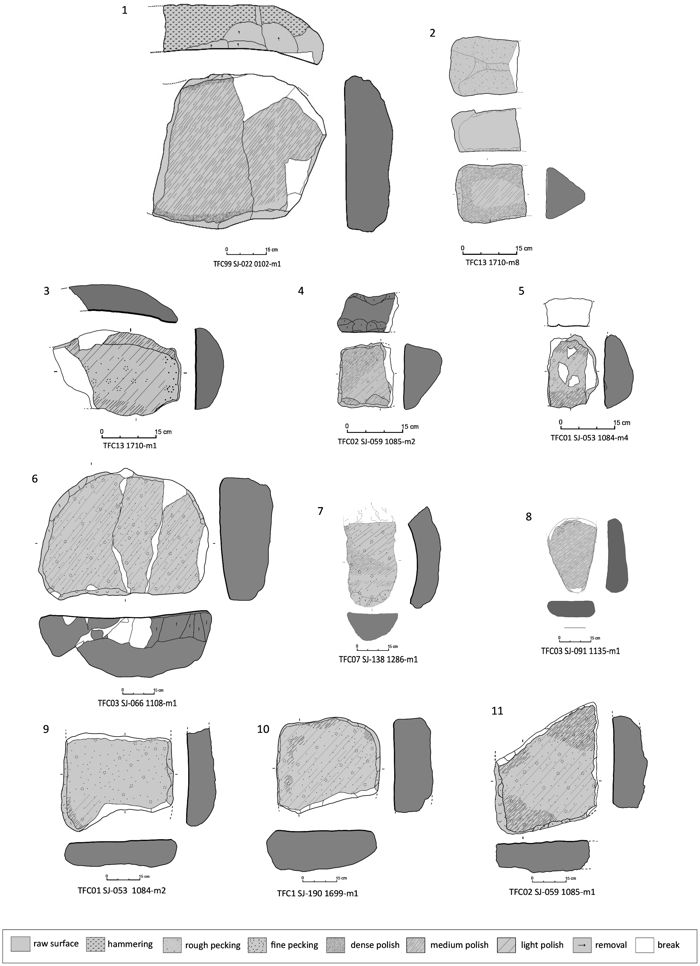

Five Type 1 querns were identified for the First Iron Age, that is, two from the Vilars 0 and three from Vilars I (Fig. 5a). The five can be broken down into three overlapping upper stones (one whole, 13441) (Fig. 6.1; 7.1) and one narrow lower stone (11631.2) (Fig. 6.10). No examples of Type 2 or 3 have been clearly identified. The remaining stages of this period comprise querns with an overlapping or covering upper stone such as nos. 5140 and 11572.1 (Fig. 6.3; 6.5). Six from these phases remain undetermined.

The results for the subsequent Early Iberian period are similar. On the one hand, there are four Type 1 overlapping upper stones (e.g., 13112.2 and 13113.2) (Fig. 6.8-9), whereas the remaining are either Type 1 or 2 (e.g., 13172.2) (Fig. 6.6). The lower stones, in turn, range between Type 1 and 2 (e.g., 13112.1 and 11286.2) (Fig. 6.11-12). Among the overlapping upper stones are several characteristic examples revealing traces of pecking with a hammer with rounded extremities, that is, either devoid of (13112.2) or with grips (13172.3) (Fig. 6.7-8; 7.2) of a type, as will be seen below, that is well established in the NE of the Iberian Peninsula.

6-9. Lower stones: First Iron Age, 10; Early Iberian period, 11-12 (drawings and infographics: A. Castellano).

(2) from the Fortress of Els Vilars (photo: GIP-UdL).

The morphological analysis of this study takes into account both the transversal section of the upper stones and the contour of the lower stones. However, many remain undetermined as it is often arduous (due to high fragmentation) to observe these parameters. A trend nonetheless appears to develop consisting of assortment of different types in the Vilars 0 phase, an increase of cases with oval contours in Vilars I, and the addition of quadrangular, trapezoidal (and others) forms in Vilars II (Fig. 5c). However, the modest number of these mills and the diversity of the section of the upper stones (Fig. 5b) do not allow observing any clear pattern.

As the characterisation and origin of the lithology of the different mills is currently underway, this study can only resort to macroscopic observations. Broadly speaking, the mills can be broken down into a roughly equal proportion of granitoids (53%) and sandstones/conglomerates (47%).

The to and fro querns of Turó de la Font

de la Canya (650-223 BC)

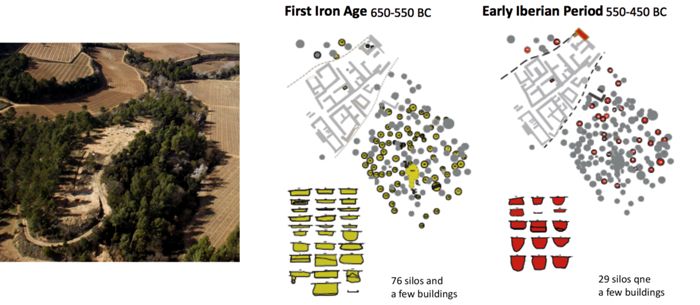

The site of Font de la Canya occupies about 10,000 m2 of the summit and slope of a small promontory about 15 km from the current Mediterranean coastline (Fig. 1; 9). Its surface today is relatively flat due to modern mechanical excavations and fillings. The site, with an occupation spanning the 7th to the 1st century BC (López Reyes et al. 2015), has been the subject of an extensive research project focusing on investigation, patrimonialisation and dissemination. Although its domestic nucleus was rather limited, the site undoubtedly featured a vast grain storage space evidenced by a combination of numerous underground silos and many archaeological finds. The different features indicate it served as a trading post that maintained contacts with other Mediterranean cultures (López Reyes et al. 2015). The finds, often exceptional and stemming from commercial exchanges with Phoenician, Greek, Carthaginian and Roman cultures, bestow the site with a cosmopolitan, commercial character. There is likewise strong evidence of the introduction of the cultivation of the vine and the production of wine dating as far back as the 7th century BC linked to Phoenician commercial exchanges.

Turó de la Font de la Canya can be broken down into four main phases:

- First Iron Age: 650-550 BC

- Iberian period

Early Iberian: 550-450 BC

Middle Iberian: 450-200 BC

Late Iberian: 200-50 BC

The mills of Turó de la Font de la Canya

The corpus of mills from Font de la Canya (202), which exceeds by far that of Els Vilars, sheds new light on the evolution of grinding stones through approximately six centuries (Fig. 8). Although the complete and fragmented mills were discovered for the most part in the fills of silos, certain were likewise collected in dwellings and work/residential areas (Zone 2, Street 1 and Enclosures 6, 7, 9 and 10 of Zone 1). The quantification of those unearthed in silos can be broken down into 54% from to the Middle Iberian period and 45% from the Early Iberian period. However, only 20% are from silos dating to the First Iron Age, the phase with the greatest number. This could be linked to a greater significance placed on the productive, agricultural and/or domestic activities carried out at the settlement initiated in the Iberian period when these tools became essential. However, one must also take into account that the silos from the First Iron Age suffered more from agricultural destruction than those from the Iberian period meaning that a great proportion of the archaeological material they contained may have disappeared (Fig. 9).

The First Iron Age phase yielded 42 fragments, all to and fro querns (Fig. 8). In most cases (70%) it is not possible to distinguish whether they are upper or lower stones (only10% can be confirmed as upper stones and 24% as lower stones).

The First Iberian phase of the Early Iberian period also only yielded to and fro querns, for the most part undetermined (50%). There is however a higher proportion, as in the previous phase, of lower stones (30%) than upper stones (20%). This phase, however, is marked by three singular upper stones which will be described in detail in the next point.

The Middle Iberian period corresponds to a greater chronological range rendering it difficult to recognise sub-periods. To and fro querns are abundant, although mostly undetermined (58%), with only a few clear upper stones (4%) and lower stones (17%). The main event worth highlighting in this phase is the introduction of the circular rotary mill, notably 21 fragments representing 22% of the total. Moreover, the upper stones of these rotary mills are more abundant (18%) than their lower counterparts (4%) (Fig. 8).

The oldest rotary mills at the site, both a fragment and an almost complete lower stone, are from silo SJ-052 (US 1081) dated to 450-350 BC (Fig. 8). Furthermore, the later examples date clearly to the 4th century BC: SJ-121 and SJ-150 (375-300 BC) and SJ-070 (in a silo which includes materials ranging from 500 to 300 BC). The remaining cases either straddle the 4th and 3rd centuries or fall in the 3rd century BC. They correspond for the most part rotary querns with a diameter inferior to 50 cm. There are nonetheless two Iberian rotary pushing mills (whose diameter is equal to or surpasses 50 cm), notably an upper stone (E-195, 1777-m2) dated to 350-250 BC and a lower stone (SJ-194, 1712-m1) from 300-225 BC. The arrival of rotary mills at this site between the 5th and 4th centuries BC thus appears to have taken place later than at the Fortress of Els Vilars where this type made its entry somewhere between the 6th and 5th centuries BC.

Evolution of the to and fro querns from Turó de la Font de la Canya

between the First Iron Age and the Early Iberian period (8th-5th c. BC)

It was only possible to classify 42 of the total 98 whole and fragmented to and fro querns from these timeframes as either upper or lower stones. Moreover, of the 42, only 31 are well-preserved enough to be placed into one of the three quern types described at the outset of this study (Fig. 10a).

b. Number of upper stones according to the form of their cross section.

The analysis of these 31 cases indicates that the overlapping upper stone type (Type 1) is most often represented in each of the two periods by respectively four upper stones and 12 lower stones (Fig. 8). The covering upper stone model (Type 2) is represented by three upper and four lower stones. Type 3, in turn, with a short stone, is represented by two upper and six lower stones, for the most part from the Early Iberian period. It must be noted, however, that in certain cases it is arduous to discern between types thus many remain undetermined or represent a type that falls between one or the other. It must likewise be highlighted that the sample per period is very small meaning that the following notions can only be regarded as indicative.

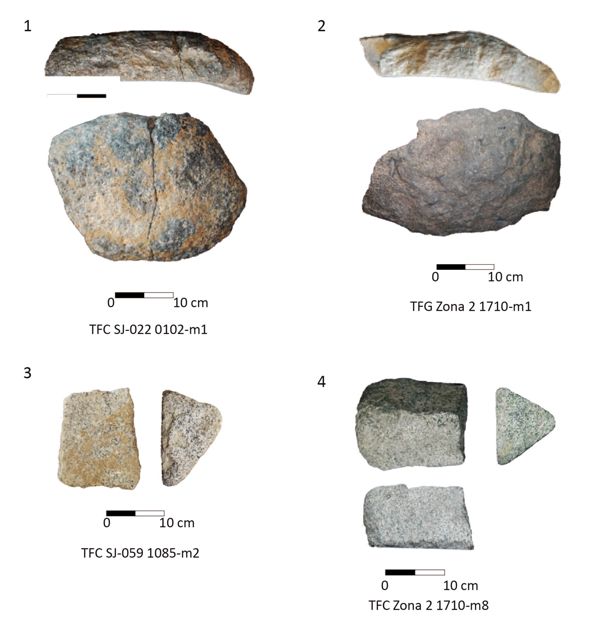

Six Type 1 querns were identified for the First Iron Age: two overlapping upper stones (noteworthy is SJ-022 0102-m1 that is practically whole) (Fig. 11.1; 12.1) and four lower stones (e.g., SJ-066 1108-m1) (Fig. 11.6). The other two types are only represented by lower stones: three associated with their covering upper stones (e.g., SJ-091 1135-m1) (Fig. 11.8) and one with a short upper stone (SJ-128 1286-m1) (Fig. 11.7). The cross sections of the upper stones of this phase reveal no trends due to the equal number of quadrangular, semi-oval, flattened semi-oval and trapezoidal cases (Fig. 10b). Although the contour of the lower stones are for the most part undetermined, certain tend towards oval, quadrangular and trapezoidal forms.

There is a greater number of to and fro querns from to the Early Iberian period (Fig. 8). Two of the 11 upper stones and eight of the 15 lower stones are of Type 1 suggesting the overlapping upper stone type to be more common (Fig. 10a). This is followed by Type 3 with a short upper stone represented respectively by two upper and five lower stones. Type 2 with a covering upper stone, in turn, is represented by three lower and one upper stones (Fig. 10a). Although the section of the upper stones for this period is mainly semi-oval, there are also quadrangular, flattened semi-oval, trapezoidal and triangular cases (Fig. 10b).

This last type with a triangular section, new and unique to this phase, is represented by two particular cases (SJ-059 1085-m2 and zone 2 1710-m8) (Fig. 11.2, 4; 12.3-4). These are two fragments of covering upper stones (in one case it might also be an overlapping type) of granite, with one of the its ends revealing a sort of socket at its top serving to accommodate the hand and the thumb assuring a better grip. It is a type with Mediterranean roots yet to be identified in the NE of Iberia whose context will be discussed below.

2. Overlapping upper stone with quadrangular grips from the Early Iberian period; 3-4. Upper stones with triangular sections from the Early Iberian period (photo: Daniel López Reyes).

Another particular upper stone is 1710-m1 from Zone 2 (Fig. 11.3; 12.2) set appart by its exceptional quadrangular hand-grips. It is one of the few cases of basalt. The findings of the geological analysis by Tatjana Gluhak were quite unexpected as it is a volcanic rock from Puy de la Nugère/Volvic in the French Massif Central and not from a far distant source. Its morphology, also distinctive, suggests it not to be an import of rough raw material but of a finished mill. In any case, as will be noted in the next section, it is not the only find at Font de la Canya from continental Gaul as the site has also yielded a group of imported metal artefacts dating to the First Iron Age.

The lower stones of this Early Iberian period, contrary to those of the previous phase, are for the most part quadrangular. There are nonetheless oval, trapezoidal, circular and rhomboid cases (Fig. 10c). Their rocks have also only benefitted from macroscopic observations. Most are granites (85%) followed by a combination of sandstones and conglomerates (11%), volcanic rocks (3%) and metamorphic rocks (1%).

Characteristic Iron Age quern types

in the NE of Iberia (8th-5th centuries BC)

Certain to and fro querns recovered from the two settlements presented in this study bear parallels with examples from other sites in the NE of the Iberian Peninsula. In spite of the fact that it has not been possible, pending further research, to classify all the querns from the other sites as either overlapping (Type 1), covered (Type 2) or short (Type 3), certain morphological features of the upper and lower stones recorded at each of the two sites under study have been identified at other regional sites.

The most common upper stones are those bearing lateral grips. Examples are known at the sites of Turó del Vent (Llinars del Vallès, Barcelona) and Penya del Moro (Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona) in 3rd century BC contexts (Fig. 13.1-2) (Portillo 2006). The latter bears a great resemblance with 13172.3 from the Fortress of Els Vilars (Fig. 6.7; 7.2) and SJ-022 0102-m1 from Font de la Canya (Fig. 11.1; 12.1). This form applies to the quern assemblage dated to the 3rd century BC recovered during early 20th century archaeological work at Taratrato (Alcañiz, Teruel) (Fig. 13.4) (Paris & Bardaviu 1926).

7. Bibracte (Saint-Léger-sous-Beuvray, France) (Jaccottey, unpublished).

A variant is the “montera” type (the name is from the characteristic bullfighter hat) common to sites in the Ebro River Valley such as Tossal del Moro de Pinyeres (Batea, Tarragona) dated to the 5th century BC (Arteaga et al. 1990) (Fig. 13.5), La Moleta del Remei (Alcanar, Tarragona) (Portillo 2006) (Fig. 13.3) and sites of the Lower Aragón such as Sant Cristòfol and Les Escudines Altes (Massalió, Teruel) (Bosch-Gimpera 1923, 644-647) (Fig. 13.4). The “montera” type is also known at Taratrato as seen on a photograph taken in the 1920s of a quadrangular upper stone bearing two hand-grip “stumps” (Paris & Bardaviu 1926) (Fig. 13.4).

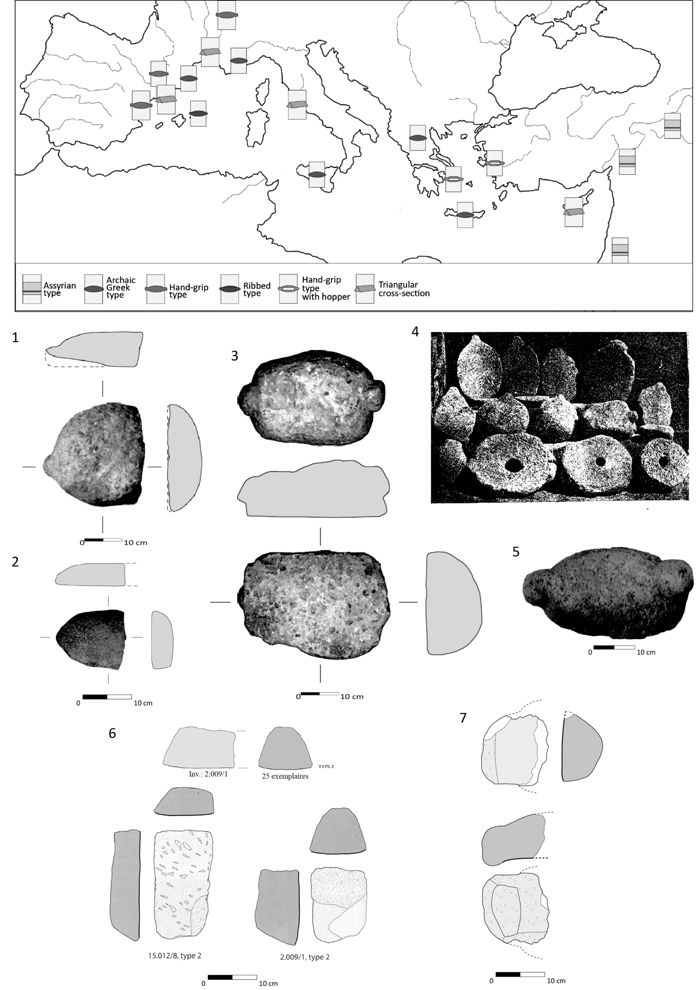

By contrasrt, the variant from Font de la Canya bearing quadrangular grips (Zone 2 1710-m1) (Fig. 11.3; 12.2) is unique to the area. As noted above, it was hewn of volcanic rock originating at an outcrop in Central France. It is thus very likely that it was manufactured in the Massif Central and attained the settlement in Iberia in a finished state. It is compelling that querns of this type, unfortunately out of context, are known at Bibracte (Jaccottey, study in progress) (Fig. 13.7). The link between the inhabitants of Font de la Canya with Central and Eastern France, whether due to commercial contacts or population movements, is reinforced by the discovery of bronze pendants dating to the middle of the 7th century BC characteristic of Hallstatt groups in the Jura and neighbouring areas of eastern France, as well as from other areas of Central Europe (López Reyes 2015).

Nor are the upper stones of elongated rectangular shape and triangular cross section from Font de la Canya (1085-m2 and 1710-m8) (Fig. 11.2, 4; 12.3-4) known to date in other contexts of northeastern Iberia. Parallels are nonetheless recorded elsewhere in the Mediterranean during the first half of the 1st millennium. Twenty-five dating from the 5th-4th century BC are recorded at the Palace of Amathonte (Cyprus) in the eastern Mediterranean (Carbillet & Jodry 2017) (Fig. 13.6). Others are known at Tel Zayit from the 10th-7th centuries BC (Greener et al., this volume) and at other Iron Age sites of Israel (Eitam, this volume). In Western Mediterranean 500-475 BC contexts they are identified at Lattara (Lattes, France) (Jaccottey et al., this volume). Therefore, this type, unlike the previous case, is clearly characteristic of the Mediterranean Basin. Future provenance research should focus on attaining a better grasp these examples of early Mediterranean exchange.

The last type of upper stone was surely coupled with rectangular lower stones such as those observed above all in the Iberian phases of Font de la Canya (Fig. 11.9-11). These quadrangular elements in certain cases labelled “tables”, not recorded with certainty at the two sites under study, are recognised elsewhere the NE of the Peninsula such as at Barranc de Gàfols (Ginestar, Tarragona) and Ciutadella de Calafell (Calafell, Barcelona) (Portillo 2006). Moreover, these “tables” were recovered in the company of upper stones of archaic Greek type at the site of Puig de Sant Andreu (Ullastret, Girona) (Portillo 2006; Alonso & Frankel 2017).

Conclusions

The current study focuses on the to and fro querns recovered during the First Iron Age and Early Iberian period at two key sites in the NE of Iberia, notably the inland Fortress of Els Vilars d’Arbeca and the coastal grain storage and trading post of Font de la Canya. Although sharing similar timeframes, they bear different characteristics, functions and geographical settings. The dynamics of grinding at each of the two also differ. There is, on the one hand, a key aspect that has not been explored in depth in this article, notably the timeframe of the introduction of the rotary motion for milling. This took place earlier at the hinterland Fortress of Els Vilars (second half of the 6th or outset of the 5th century BC) than at the coastal trading post of Font de la Canya where it is not recognised until the end of the 5th or outset of the 4th century BC. This reinforces, once again, the finding that the introduction of rotary of mills is a fully indigenous phenomenon bearing no link to imports from elsewhere in the Mediterranean world (Alonso 2015).

The “cosmopolitan” character of the Turó de la Font de la Canya is nonetheless confirmed by certain to and fro querns, notably models bearing quadrangular handles of central European type or rectangular upper stones with triangular sections which are clearly Mediterranean. These types are not recorded in the hinterland where the traditions of the First Iron Age and the Iberian world predominate, especially the models bearing hand-grips.

In fact, the data gleaned from these sites reinforces a phenomenon recognised in other studies (e.g., Alonso & Frankel 2017). The introduction of the hopper rubber (also known as the Olynthus mill) and the invention of the rotary mill in the Mediterranean, each event dating to the middle of the 1st millennium, were preceded by a series of morphological changes among the to and fro querns initiated in the 7th century BC. These changes are evidenced in the Eastern Mediterranean by the type known as the Assyrian quern recorded in the Near East between the 9th and 4th centuries BC characterised by a longitudinal cutting across the back of its upper stone serving to insert a rod to drive it (Bombardieri 2008, 2010). There were likewise fairly standardised querns in Greece from the 7th century BC of “Archaic” Greek type often with “eye-shaped” upper stones and pointed extremities (Amouretti 1986; Runnels 1988), features affording a better grip. Moreover, a variant of this type bearing well-developed lateral grips is recorded in Greece between the 5th and 1st century BC (Amouretti 1986).

Despite these other types, the Eastern Mediterranean’s predominant mill driven with a to and fro motion is the hopper rubber. Its more standard type is rectangular with an upper stone bearing opposite cuttings (to attach a projecting rod) and a V-shaped cutting (hopper) which permits a continuous feeding of grains (Frankel 2003). It was set on a table or platform and, as depicted by iconography (Rostovtzeff 1937), operated from a standing position. Recent experimental work suggests it could also have been driven from a sitting position (Chaigneau et al., this volume) by means of a wooden rig. As noted above, the western Mediterranean since the Iron Age also saw other new types of querns. Worth highlighting apart from those cited are the very particular large “molons” (“ribbed” type) characteristic of Minorca whose upper stones backs reveal a continuous longitudinal rib (Portillo et al. 2014).

Although these variants appearing since the first half of the 1st millennium BC point to attempts to improve the means of operating the querns and increasing their yield, the true innovation in milling did not arrive until the introduction of the rotary motion.

Acknowledgements

The current study forms part of the MOBICEX research project Mobility, Circulation and Exchange in the Western Catalonian Plain between the 3rd and the 1st millennium BCE of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2019-110022GB-I00, financed by MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033) and ARQHISTEC. Food Economies and Population Dynamics in the Western Mediterranean: Archaeology and History of pre-modern societies (2021SGR01607). Research on the querns of the Fortress of Els Vilars is carried out mainly with the support of the Department of Culture of the Generalitat de Catalunya, the Arbeca City Council and the University of Lleida. That of Turó de la Font de la Canya, in turn, was supported by the City Council d’Avinyonet del Penedès, the Department of Culture of the Generalitat de Catalunya, the Diputació de Barcelona, the Designation of Origin of “Vins del Penedès” and “Bodegas Torres”.

Bibliography

- Adroher, A. and Molina, E. (2014): “La molienda en la Protohistoria del mediodía peninsular ibérico”, in: Alonso, N. (ed.), Dossier: Molins i mòlta al Mediterrani occidental durant l’edat del ferro, Revista d’Arqueologia de Ponent, 24, 215-237.

- Alonso, N. (1999): De la llavor a la farina. Els processos agrícolas protohistòrics a la Catalunya Occidental. Lattes, CNRS, Monographies d’Archéologie Méditerranéenne, 4.

- Alonso, N. (ed.) (2014): Dossier: Molins i mòlta al Mediterrani occidental durant l’edat del ferro, Revista d’Arqueologia de Ponent, 24: 113-136.

- Alonso, N. (2015): “Moliendo en ibero, moliendo en griego: aculturación y resistencia tecnológica en el Mediterráneo occidental durante la Edad del Hierro”, Vegueta, 15: 23-36.

- Alonso, N. (2019): “A first approach to women, tools and operational sequences in traditional manual cereal grinding”, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 11: 4307-4324.

- Alonso, N., Aulinas, M., Garcia, M.T., Martín, F., Prats, G. and Vila, S. (2011): “Manufacturing rotary querns in the 4th century BC fortified settlement of Els Vilars (Arbeca, Catalonia, Spain)”, in: Williams D. and Peacock, D. (eds), Bread for the people, Southampton Archaeology Monograph, Southampton, 55-65.

- Alonso, N. and Frankel, R. (2017): “Survey of ancient milling systems in the Mediterranean”, in: Les meules du Néolithique à l’époque médiévale: technique, culture, diffusion, Revue Archéologique de l’Est Suppl. 43, 461-478.

- Alonso, N. and Pérez-Jordà, G. (2014): “Molins rotatius de petit format, de gran format i espais de producció en la cultura ibèrica de l’est peninsular” in: Alonso, N. (ed), Dossier: Molins i mòlta al Mediterrani occidental durant l’edat del ferro, Revista d’Arqueologia de Ponent, 24, 239-255.

- Alonso, N., Pérez-Jordà, G. and López Reyes, D. (2016): “Les moulins rotatifs poussés du monde ibérique: caractéristiques et utilisation”, in: Jaccottey, L. and Rollier, G. (eds), Archéologie des moulins hydrauliques, à traction animale et à vent, des origines à l’époque médiévale. Actes du colloque international, Lons-le-Saunier du 2 au 5 novembre 2011, Presses Univeau Franche-Comté, 559-558.

- Alonso, N., Bernal, J., Castellano, A., Escala, O., Gonzàlez, S., Junyent, E., López, J.B., Martínez, J., Moya, A., Nieto, A., Oliva, J.O., Prats, G., Tarongi, M., Tartera, E., Vidal, A. and Vila S. (2020): La Fortalesa dels Vilars (Arbeca, Les Garrigues) durant d’Ibèric Antic (550-425 ANE), in: Torres, M., Garcés, I. and González, J.R. (eds), Projecte Ilergècia: territori i poblament ibèric a la plana ilergeta. Centenari de les excavacions del poblat ibèric del Tossal de les Tenalles de Sidamon (1915-2015), Actes de la XLV Jornada de Treball, Sidamon 2017, Grup de Recerques de les Terres de Ponent, Sant Martí de Maldà/Riucorb, 85-118.

- Amouretti, M.-C. (1986): Le pain et l’huile dans la Grèce antique. De l’araire au moulin. Centre de Recherche d’Histoire Ancienne, vol. 67. Paris.

- Anderson, T.J. (2016): Turning Stone to Bread: A Diachronic Study of Millstone Making in Southern Spain, The Highfield Press, Southampton.

- Arteaga, O., Padró, J. and Sanmartí, E. (1990): El poblado ibérico del Tossal del Moro de Pinyeres (Batea,Terra Alta, Tarragona). Monografies Arqueològiques, 7, Barcelona.

- Bombardieri, L. (2008): “The millstones and diffusion of new grinding techniques from Assyrian Mesopotamia to the Eastern Mediterranean basin during the Iron Age”, in: Monozzi, O., Di Marzio, M.L. and Fossataro, D. (eds), Proceedings of the IX Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology, Chieti, February, 24-26, 2005, Oxford, 487-494.

- Bombardieri, L. (2010): Pietra da Macina, Macine per Mulini. Definizione e sviluppo delle tecniche per la macinazione nell’area del Vicino Oriente e del Mediterraneo orientale antico, BAR Int. Ser. 2055, Oxford.

- Bosch Gimpera, P. (1923): “Les Investigacions de la cultura ibèrica al Baix Aragó”, Anuari MCMXV-XX, 641-671.

- Carbillet, A. and Jodry, F. (2017): “Les outils de mouture du Palais d’Amathonte (Chypre) à l’âge du Fer: premiers résultats”, in: Les meules du Néolithique à l’époque médiévale: technique, culture, diffusion, Revue Archéologique de l’Est Suppl. 43, 449-459.

- Équipe Alorda Park, (2002): “Les meules rotatives du site ibérique d’Alorda Park (Calafell, Baix Penedès, Tarragona)”, in: Procopiou, H. & Treuil, R., dir., 2002, Moudre et broyer: l’interprétation fonctionnelle de l’outillage de mouture et de broyage dans la Préhistoire et l’Antiquité, Éd. du CTHS, 2002, Paris, 155-175.

- Frankel, R. (2003): “The Olynthus Mill, Its Origin and Diffusion: Typology and Distribution”, American Journal of Archaeology, 107, 1-21.

- Jaccottey L., Alonso, N., Defressigne S., Hamon C., Lepareux-Couturier S., Brisotto V., Galland-Crety S., Jodry F., Lagadec J.P., Lepaumier H., Longepierre S., Milleville A., Robin B. and Zaour N. (2011): “Le passage des meules va-et-vient aux meules rotatives en France”, in: Krausz, S., Colin, A., Gruel, K., Ralston, I. and Dechezleprêtre, T. (dir.), L’âge du Fer en Europe: mélanges offerts à Olivier Buchsenschutz, Bordeaux, Ausonius Mémoires 32, 405-419.

- Junyent, E. and López, J. B. (2016): The Vilars d’Arbeca Fortress. Land, Water and Power in the Iberian World, Museu de Lleida, Catàlegs, 3, Lleida.

- Longepierre, S., (2012): Meules, moulins et meulières en Gaule méridionale du IIe s. av. J.-C. au VIIe s. ap. J.-C. , Monographies d’Instrumentum, 41, Montagnac.

- Longepierre, S., (2014): Les moulins de Gaule méridionale (450-1 av. J.-C.): types, origines et fonctionnement, in: Alonso, N. (ed), Dossier: Molins i mòlta al Mediterrani occidental durant l’edat del ferro, Revista d’Arqueologia de Ponent, 24: 289-309.

- López Reyes, D., Asensio, D. Jornet, R. and Morer, J. (2015): La Font de la Canya. Guia Arqueològica. Jaciment ibèric de la Font de la Canya (Avinyonet, del Penedès). Un centre de mercaderies a la Cossetània ibèrica origen de la vinya, Institut d’Estudis Penedesencs.

- López, J.B., Junyent, E. and Alonso, N. (2020): Chapter 13: “Architecture, Power and Everyday Life in the Iron Age of North-eastern Iberia. Research from 1985 to 2019 on the Tell-like Fortress of Els Vilars (Arbeca, Lleida, Spain)”, in: Blanco-González, A. and Kienlin, T. (eds), Current approaches to tells in the prehistoric Old World, Oxford, 189-208.

- Paris, P. and Bardaviu, V. (1926): Fouilles de la région d’Alcañiz (Province de Teruel). Bibliothèque de l’École des Hautes Études Hispaniques, fascicule XI, 1. Bordeaux.

- Portillo, M. (2006): La Mòlta i Triturat d’Aliments Vegetals Durant la Protohistòria a la Catalunya Oriental. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Universidat de Barcelona.

- Portillo, M., Llergo, Y., Ferrer, A., Anglada, M., Plantalamor, L. and Albert, R.M. (2014): “Actividades domésticas y molienda en el asentamiento talayótico de Cornia Nou (Menorca, Islas Baleares): resultados del estudio de microfósiles vegetales”, in: N. Alonso (ed.), Molins i mòlta al Mediterrani occidental durant l’edat del ferro. Revista d’Arqueologia de Ponent 24: 311-321.

- Py. M. (1992): “Meules d’époque protohistorique et romaine provenant de Lattes”, in: Py, M. (dir.), Recherches sur l’économie vivrière des lattarenses, Lattara 5, 183-232.

- Rostovtzeff, M. (1937): “Two Homeric Bowls in the Louvre”, American Journal of Archaeology, Jan-Mar., 41, 1, 86-96.

- Runnels, C.N. (1988): A Diachronic Study and Economic Analysis of Millstones from the Argolid, Greece. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Indiana University.

- Wefers, S. (2011): “Still using your saddle quern? A compilation of the oldest known rotary querns in western Europe”, in: Williams D. and Peacock, D. (eds), Bread for the people, Southampton, Southampton Archaeology Monograph: 55-65.

- Zimmermann, A. (1988): Stein. in: Boelicke U., Brandt V., Lüning J., Stehli P. and Zimmermann A. (eds), Der bandkeramische Siedlungsplatz Langweiler, 8, Gemeinde Aldenhoven, Kr. Düren. Köln/Bonn Rhein. Ausgr., 569-787.