The protohistoric period in Europe is the theater of very diverse funeral treatments, from simple burial as it is most often envisaged, to cremation, including specific positioning, remodeling of tombs, recovery of bones, etc. The development of archeothanatology methods is therefore essential for the study of funerary behavior. It always starts on the excavation field, during the discovery, with adapted excavation and recording methods which will then allow us to interpret the funeral gestures. The analysis of these gestures will make it possible to identify funeral practices, which themselves result from ritual sequences.

The taphonomic analysis of the burial is the key point to distinguish the action of man from natural evolution since the mortuary deposit. The osteological observations will make it possible to identify the sex of the deceased and his age at death. This information is then used to understand the recruitment of the funeral complex and to get an idea of the concerned population.

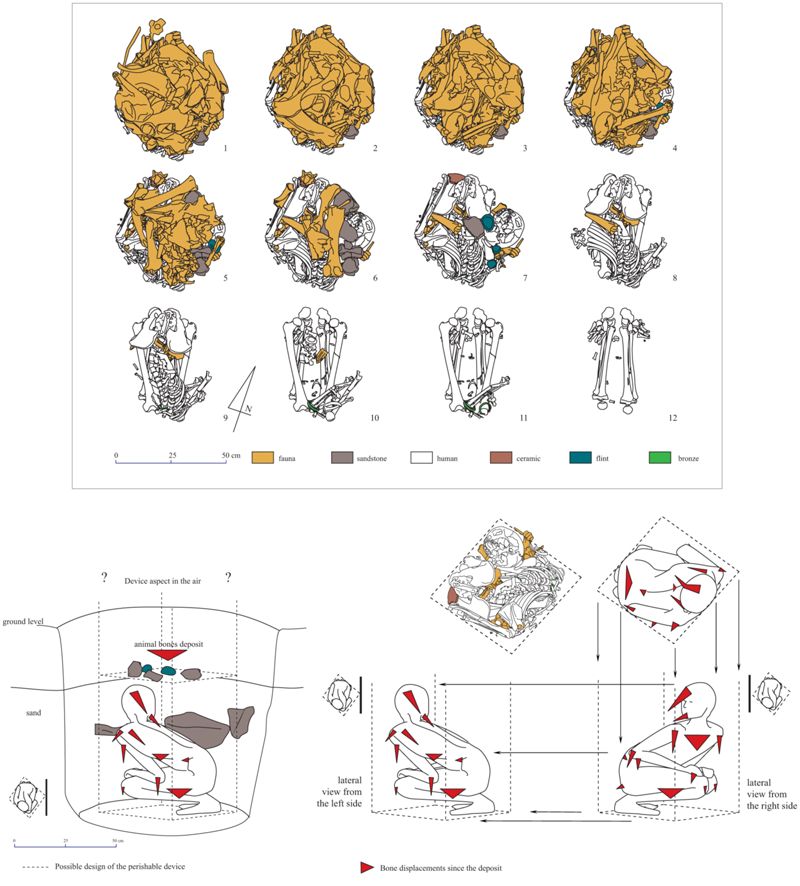

For example, for the beginning of the Late Bronze Age (XIV-XII c.BC), in the south-east of the Paris Basin, we were able to demonstrate that a third of the subjects were buried in a vertical, seated position, in the same funerary spaces as the other subjects laid down in a lying position, most often on their back. In addition, these burials rarely contain children, while in protohistoric populations the expected infant and child mortality is very high (around 25% before the end of the first year and as much before the age of 5 years old). In these necropolises, the bronze goods, particularly the pins, do not seem to be attributed to chance, and we have been able to identify a “social skin”, which is a set of criteria allowing the person to be recognized by the members of his community and may be larger than this.

The study of cremations is more complex due to the deformation and fragmentation of bones by the exposition of the pyre’s fire. Then, it becomes a matter of meticulous work of recognizing the bone pieces in order to obtain information on the funeral procedures, the organization of the deposit, the implementation of the cremation, etc. And try to reproduce the funeral behavior. For example, for the second Iron Age, on the site of Urville-Nacqueville, Normandy, it was shown that the subjects were buried if they died before the age of 7-8 years, while the oldest were mostly the object of cremation.

It is therefore both observation and description skills in the field, then biological analyzes and data crossing that are necessary for the anthropologist and the archaeologist jointly to try to reconstruct the behavior in front of death of the protohistoric societies, and more generally for all past societies.

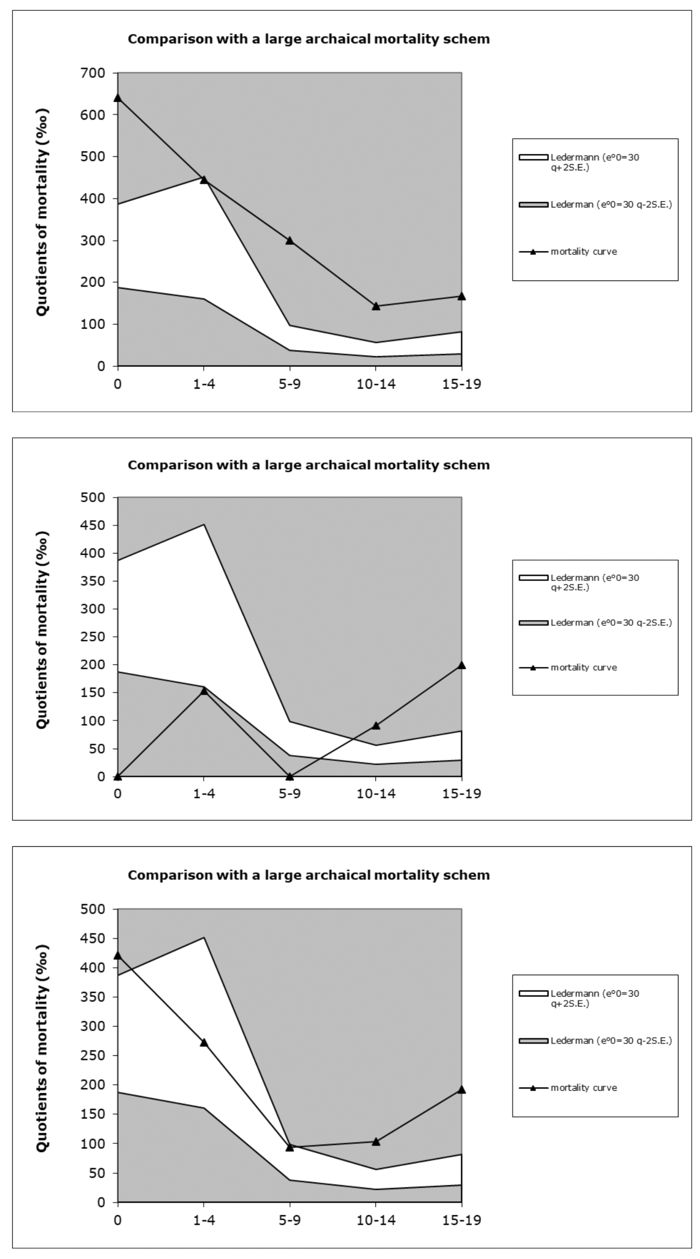

A. Mortality rates for buried corpses at Urville-Nacqueville (Normandie, France). All the age categories are over represented.

B. Mortality rates for buried corpses at Urville-Nacqueville (Normandie, France). The age categories under 9 years old are under represented, meaning these part of the population is not burned after death.

C. Mortality rates for the global population at Urville-Nacqueville (Normandie, France). The younger age categories are represented as expected, meaning all the popultaion could be there for thoses ages. Here, the over representation of [10-19] is actually induce by a lack of adult people in this funerary site.