The knowledge of ancient societies is expressed in a significant way through funerary remains: indeed, the moment of death crystallizes important challenges allowing us to approach different aspects of these societies, whether it be their social, economic, or cultural functioning or the field of beliefs. Studied at different scales, from the burial site to the funerary space, these remains constitute privileged witnesses of cultural heritage reflected in architecture, furniture, but also in mortuary practices, land heritage, since for many human groups, the right to property is based on the assertion “my land is where my fathers’ bones lie…”, and finally genetic heritage that can be analyzed from the bone remains that are unearthed. Over the last twenty years, the evolution of methods and the increase in discoveries thanks to preventive archaeology have made it possible to renew our knowledge both at the scale of the burial site and of the funerary spaces. The contributions to this chapter bear witness to this for different periods.

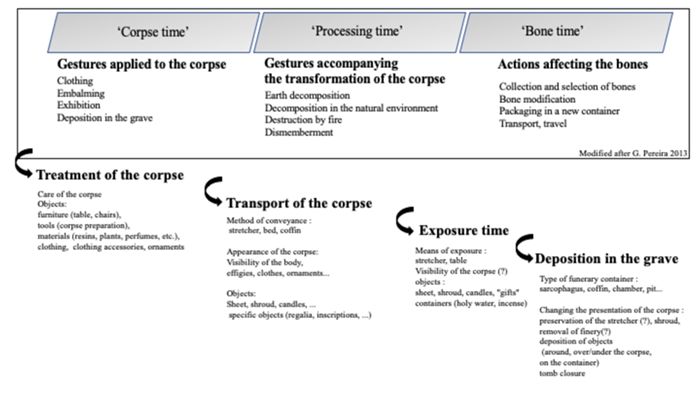

Over the last twenty years, funerary archaeology has benefited from major advances which are essentially due to the simultaneous consideration of the biological and cultural dimensions of the mankind, and this duality appears through human remains which bear witness to the history of settlements, diet, diseases, and mortality. At the interface between Forensic Medicine and Funerary Archaeology, archeothanatology aims to study all aspects of the phenomenon of Death in ancient societies. This discipline is based on a dynamic reading of funerary deposits and deliberately places the deceased at the center of its discourse. 1 This approach requires knowledge of the processes by which the deceased passes from the state of organic remains to that of a ‘mineral’ skeleton, whatever the cultural (funerary treatments) and environmental (climate, hygrometry, fauna, etc.) contexts.2 Considering the taphonomy of the skeleton, but also of all the perishable materials, makes it possible to restore new funerary gestures and to take a new look at the objects associated with the deceased. The increased possibilities of archaeometry analysis are contributing to these new views.

References

- Duday, H., 2012: “L’archéothanatologie, une manière nouvelle de penser l’archéologie de la mort”, in: Beaune, S. & Francfort, H.-P. (dir.), L’archéologie à découvert, Paris, p. 62-71.

- Pereira, G., 2013: “Introduction”, Une archéologie des temps funéraires ?, Les nouvelles de l’archéologie, 132, p. 3‑7, URL: https://journals.openedition.org/nda/2064.