Introduction

Ground stones throughout prehistory served to produce, process and store sources of subsistence as well as to manufacture other stone tools (Fig. 1). Many of these tasks involved resorting specifically to ground stones and to-and-fro driven querns, at least at some stage of their operational sequence. Numerous records in Mesopotamia shed light on the preparation of staples, notably barley and wheat (Postgate 1984; Wright 1992, 33), beans and lentils (Wright 1991, 35, footnotes 91-93) and other materials such as ores and pigments. Wall paintings and other representations in Egypt likewise offer information on bread preparation and beer brewing (Wilson 1988; Tooley 1995; Samuel 1999). Classical writers such as Cato, Pliny and Varro likewise describe the use of mortars and grinding tools mainly to prepare foodstuffs (On Agriculture, Ch. II 14; Nat. Hist., Vol V, book XVIII, Ch XXIX, 109-116: 256-263; On Agriculture, Ch. 138, 145), uses that are also bolstered by ethnographic research (Dalman 1933; Avitzur 1972; Hillman 1984, 1985; Turkowski 1996). Thus the systematic study of their function in daily life among ancient societies yields vital economic, social and cultural data.

The subject of stone tools in the ancient Near East remained marginal until the 1990s (Wright 1992, footnote 1; Ebeling & Rowan 2004). Eighty years ago, Albright exemplified this neglect when stating that there is no particular need to study these artefacts as they afford “little chronological significance” (Albright 1938, 84). Yet a minority of other early archaeologists bemoaned this attitude. The celebrated Gordon Childe, in his early and seminal molinological article, states that this type of research

unfortunately it is still rather thin; excavators of classical and barbarian sites have generally been too preoccupied with statuary and art objects on the one hand, with types accepted as chronologically significant on the other, to provide the historian of science with the data he craves. (Childe 1943, 19).

Unfortunately, few past archaeologists in the study region have recognised the crucial role of grinding stones hewn from blocks or carved into bedrock (Macalister 1912; Amiran 1956; Kraybill 1977). Only the past few decades have seen a systematic change in attitude towards stone tools as essential elements of archaeological reports (e.g., Elliott 1991). Hence today, most excavations regularly collect and accurately record ground stones by means of more orderly methods (see Baysal & Wright 2002 for what remains a utopian method).

As a result, detailed reports on ground stone assemblages initiated by excavators (although still under revision) are becoming more common. Examples are the comprehensive publications from the City of David and Manahat (Hovers 1996; Milevski 1998) and subsequent site reports by Amihai Mazar for the studies of the sites of Tel Batash-Timnah, Beth Shean and Tel Rehov (Cohen-Weinberg 2001; Yahalom-Mack 2006, 2007; Yahalom-Mack & Mazar 2006; Yahalom-Mack 2007; Petit 2020). Others include Tel Yoqneʿam (Ben-Ami 2005a, 2005b) and Tel Miqne-Ekron (Milevski 2019). Less common are thematic surveys such as those by Wright (1991, 1992) and Dubreuil (2002, 2004, 2008) for the prehistoric periods and later periods (Frankel 1999; Eitam 1979, 1980, 1996, 2005; Eitam et al. 2015; Eitam & Schoenwetter 2021). Nonetheless, certain excavators of major ancient historical sites in Israel still relegate these types of tools to simply a catalogue accompanied by illustrations devoid of analyses. These include the listings for the sites of Megiddo, Lachish and Hazor, which at times include drawings (e.g., Sass 2000, 2004; Sass & Ussishkin 2004; Sass & Cinamon 2006; Ebeling 2012; Rosenberg 2013; Yadin et al. 1958; Yadin et al. 1960; Yadin et al. 1961). This approach, unfortunately, ignores a significant amount of data (probably equal in importance to that of the pottery) from which it is possible to glean information on several key economic and cultural aspects.

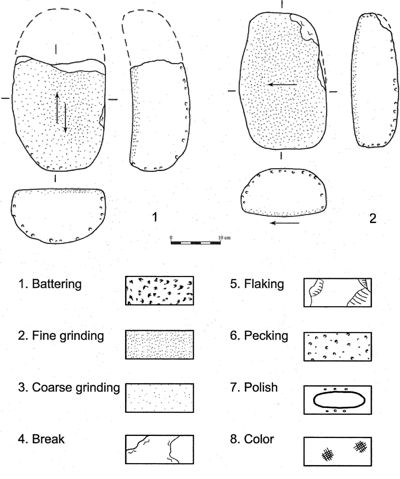

A major problem linked to ancient Near East stone tool research is the need for more consensus on a critical analytic methodology, an absence that has hampered investigating and determining their function (see criticism in Squitieri & Eitam 2019, 1-8; for other questions see Alonso & Frankel 2017, 1-2). Furthermore, stone tools usually were intentionally designed for specific usage. However, they were often multifunctional or reusable, altering their function throughout their “lives.” A critical issue of ground stones study is thus to attempt to grasp the function and the significance of the range of tasks of any single object. A more flexible approach can thus be attained by applying a multi-variable typology (Eitam 2009a, 88) differing from a system based on single variables (Adams & Adams 1991; Adams 2013). For the same reason, it is insufficient to only publishing catalogues of ground stones devoid of observations of the changes throughout their lifespan (see Appendix A for a detailed description).

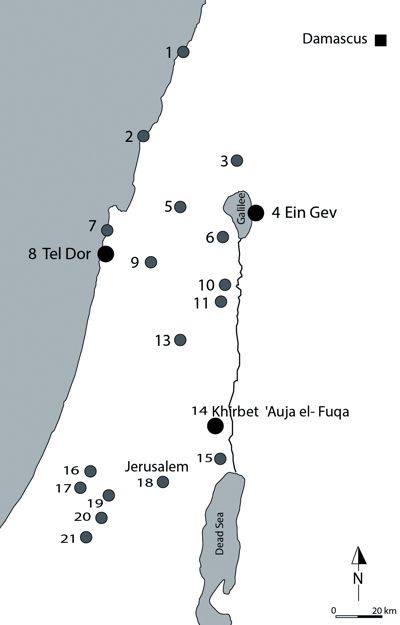

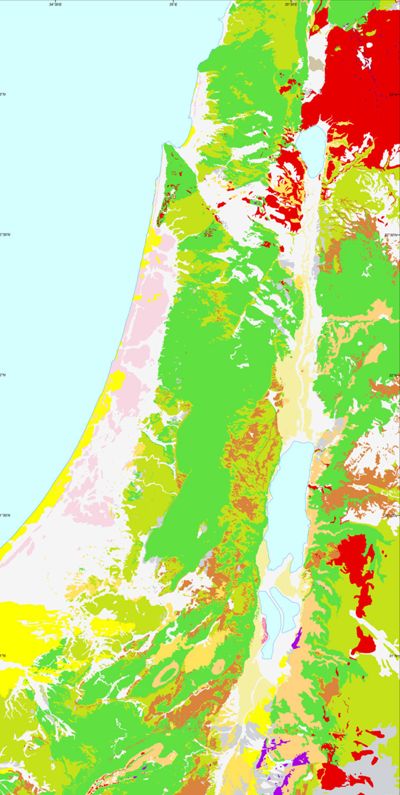

This article thus presents a short history of grinding tools from a number of sites in Israel (Fig. 2) an overview of the raw materials serving to make them, and the “industrial” design of certain from the Iron Age. This involves a description of their types, their potential reuse, and their context. This is followed by a summary of their technological developments and socio-economical, cultural and at times political implications. For a better understanding of their contexts, this study advances a typological classification of the cases from the Iron Age and a detailed catalogue of the tools three sites, notably Area G of Tel Dor (Eitam, unpublished c; Eitam in press a), Ein Gev and Khirbet ‘Auja el-Fuqa (Appendix A).

A short history of grinding tools

There are few cases of grinding tools in the Southern Levant during the Upper Palaeolithic (Wright 1991). They gain in prevalence in the subsequent Natufian Culture of the Late Epipalaeolithic. These narrow oblong sandal-shaped implements were either hewn into the bedrock or portable stones were combined with small oval handstones. They attained a high point in the Late Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Age I (4000-3000 BC) as manifest by dozens carved into bedrock outcrops within the sites, a practice that continued in rural areas as late as the Middle Bronze Age (2000-1550 BC; Eitam 2009b).

More efficient querns with larger upper and lower stones (henceforth, handstones and slabs) date to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B coinciding with the early domestication of cereals and legumes. Only a few earlier cases of rather large oval slabs coupled with a loaf-shaped handstones are recorded in the Early Bronze II (3000-2700 BC; Sass 2000, fig. 12.4). It is a type that became common in the Pottery Neolithic with the expansion of the cultivation of cereal.

After the introduction of the grooved mill characterised by shallow longitudinal cuttings on the back of their upper stones (serving to insert a rod to drive the mill) in the middle of the 1st millennium BC, the diversity of milling systems increased considerably. These included the introduction of the Olynthus mill originating in the Phoenician Late Iron Age II, a type known in Israel as late as the 6th century AD (Frankel 2003). Noteworthy is also the introduction into the Southern Levant during the Hellenistic Period of the rotary quern and the subsequent larger Pompeian mill in the 1st century BC (Frankel 2003; Alonso & Frankel 2017). However, it must be noted that manual grinding with a to-and-fro motion was still widely in use until the introduction of the watermill into the region in the Late Arabic period (Lewis 1997; Ad et al. 2005), a complex mechanism that endured in Israel well into the 19th and 20th centuries.

Raw materials

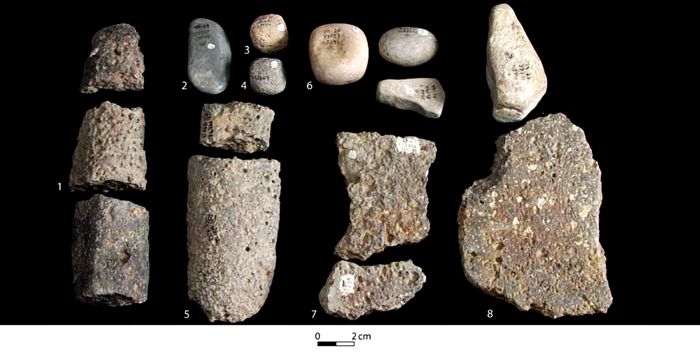

The choice of the raw material serving to manufacture the grinding stones varied according to their properties (hardness and bite) and the distance of the outcrop. Most of the rocks serving as grinding stones at the site of Ein Gev (Iron Age I and IIA; 11th until the 8th century BC; Sugimoto 2015) on the eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee are basalts (67%) from nearby outcrops (Fig. 3). Other rock types, such as hard limestones (more suitable for abraders and polishers) and soft limestones are less frequent (24%). Flint (including calcareous flint) is even less used (6%), while the remaining were hewn from several unusual rocks.

Tel Dor is located along the northern seashore of Israel about 50 km from the nearest basalt outcrops. The Early Iron Age courthouse of Area G (phases 9-6) ranging from the 11th to the first half of the 10th centuries BC (Gilboa’, Sharon & Zorn 2014, 46) yielded a corpus of 343 stone tools marked by a high ratio of basalts. These volcanic stones can be broken down into vesicular basalts (16%) (Fig. 1: 7-8), porous basalts (27%) (Fig. 1: 5), feldspar basalts (31%) (Fig. 1: 1 below) and undetermined basalts (26%) (Eitam, unpublished c). From this lot, one can conclude that vesicular basalts were preferred for grinding tools (as opposed to pounding tools), whereas feldspar and porous basalts served more for lower stones while porous basalt was the choice for the upper handstones. The numerous imported basalts and other high-quality tools unearthed at in Area G of Tel Dor1 point to far-reaching trade networks and suggest that the settlement was prosperous during Iron Age I.

The ratios of these three groups of raw materials of Stratum V of Tel Dor dated to the 9th century BC are similar: basalt (69%), limestone (22%) and calcareous flint (9%). The relatively rich assemblage (28 items) of this site delving into the ratio of the different types of basalt and its use. It is notable that 47% of the vesicular basalt served to manufacture slabs (including a massive bowl and a basin), whereas 32% of the porous basalt served for handstones, slabs and a pounder. Feldspar basalt (21%), in turn, served for other items such as a fine bowl, a pounder and a figurine (Eitam in press). These proportions of basalt and limestone are similar to the ground stone assemblage of Tel Batash (Cohen-Weinberger 2001, table 47) and reflect a balance between need and circumstance.

A different situation applies to the stone tools of the single-period Iron Age I fortified site of El-Ahwat, 15 km to the northeast of Tel Dor. The general ratio at this site is 44% basalt compared to 56% of local, mainly crumbly, calcitic stones (Eitam unpublished a). Moreover, many of its basalt tools are of inferior quality, possibly collected from nearby Zichron outcrops (Segev & Sass 2009) suggesting limited access to resources and trade networks. Another small yet significant cultic site from the Iron Age I is Mount Ebal in the Samaria Highland (Zertal 1987). It reveals a relatively high ratio (48%) of quality basalt primarily in the form of loaf-shaped querns (Eitam, unpublished b, see conclusion).

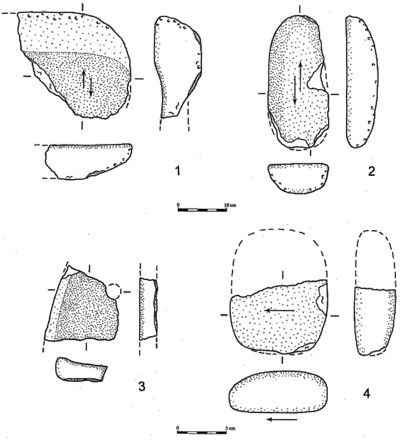

More than half of all the stone tools (20) collected on the surface of the Iron Age II site of Khirbet ‘Auja el Fuqa, a fortified city near Jericho (Eitam 2007), were hewn from local rocks (limestone, chalk with flint breccia) poorly suited for grinding (Fig. 2 and 3). The remaining are of more suitable imported materials, notably hard sandstone (4) and basalt (9). The tool’s shape was determined by the nature of the local softer raw material (e.g., the oval slab, Fig 4: 1). Others retained the standard Iron Age features (e.g., a loaf-shaped lower stone and a small oval-shaped handstone (Fig. 4: 2 and Fig. 5: 4). This evidences a flexible approach by the craftsmen while simultaneously retaining traditional forms.

Tel Miqne, an Iron Age IIC city and the Philistine kingdom of Ekron on the southern seashore of Israel, reveals a ratio of about 75% of inferior local rocks compared to 25% of superior imported materials (Milevski 2019). The inferior stones consist mainly of limestoneand probably also nari (crumbly limestone) (Eitam 1996). This appears to confirm the low socio-economic state of the thousands of workers taking part in the olive oil enterprise of Ekron in the 7th century BC.

The assemblage of Khirbet Qeiyafa, a fortified city from the end of the 11th-10th century BC (single short occupation) on the western edge of the Low Hill region of Judea, differs radically from other Iron Age sites. Most of its querns (80%) are roughly made of hard and soft limestone, flint, and chalk, while only about ten are of basalt (Cohen-Klonymus 2014). This high proportion of less suitable stones is unusual and contrasts with Early Iron Age assemblages elsewhere in Iron Age I Israel (see conclusions).

Mill types

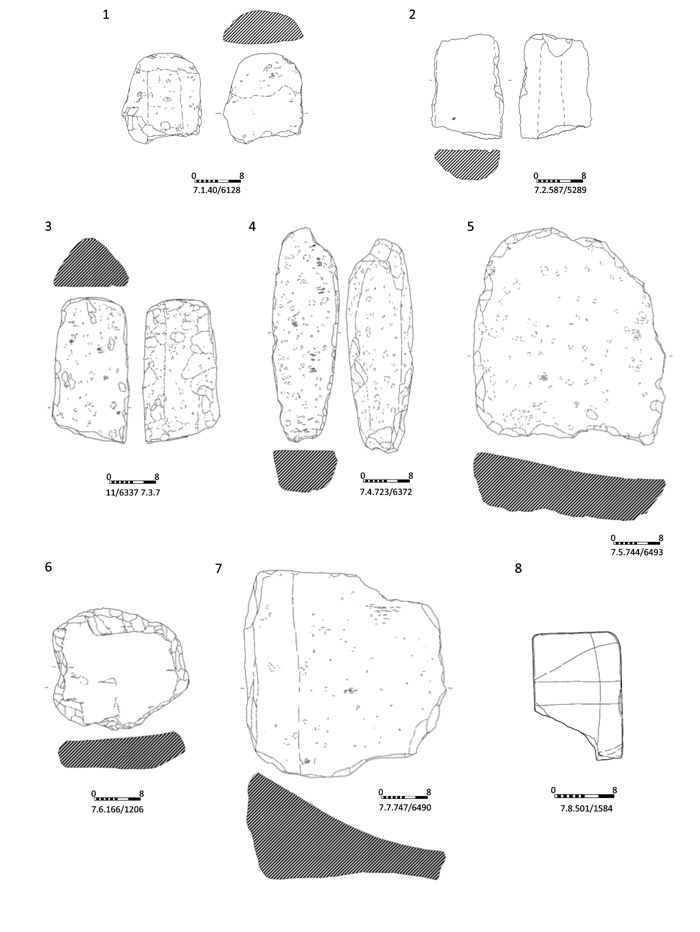

Three types of hand querns are common to the Iron Age of Israel: 1) narrow, loaf-shaped slabs (Fig. 6: 1-3 and fig. 9: 4) coupled with small, oval, square, or irregular handstones (Fig. 5: 4 and Fig. 7: 1-2) and 2) large square slabs (Fig. 9: 7) associated with loaf-shaped handstones (Fig. 6: 2). The latter type can be broken down into two subtypes: 3a) the longitudinal section of the first is narrow and square with bifacial grinding surfaces (i.e., top and bottom) (Fig. 9: 6) mainly operated with loaf-shaped handstones (Fig. 8: 4) that cover the width of the slab without leaving lateral margins; and 3b) The second subtype is thicker and diagonal in the longitudinal section, at times revealing lateral margins (Fig. 9: 7).

(Appendix A: B98687).

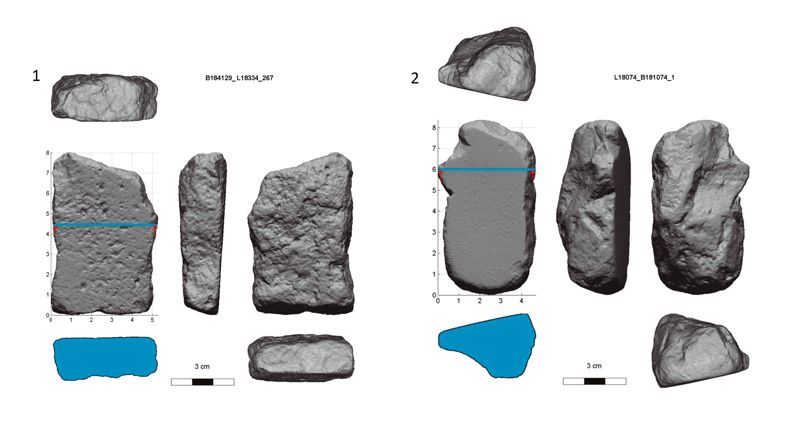

(Appendix A: B184129); 2. Small irregular, partly modified handstone and polisher; limestone

(Appendix A: B181074/1).

Loaf-shaped mills

Most of quern slabs dating to the Late Bronze and Iron Age in Israel were loaf-shaped and coupled with small handstones. They were driven with a to and fro motion over a narrow surface.2 These slabs reveal concave or flat longitudinal sections (Fig. 6: 1-2 and Fig. 9: 4), while the grinding surfaces of their handstones reveal flat or convex longitudinal and transversal sections (Wright 1992).

Numerous loaf-shaped lower stones were “transformed” into loaf-shaped handstones by flipping them upside-down (see Wright 1992 for the definitions of loaf slab and handstone).3 This is the case of 150 (!) stones from the site of Tel Rehov corresponding to 38% of all complete mills. Petit described mill type 1b1 as being “asymmetric two hands grinding slab…”. About one-third of the [52] stones of this type reveal “…a concave grinding face along the longitudinal axis” (Petit 2020, fig. 7:2, fig. 3, fig. 8:2, fig. 9:2; pl. 17.2). Unfortunately, archaeologists have not adopted the correct classification system of loaf grinding slabs established by the first excavators of Hazor (Yadin et al. 1958, 1960, 1961). It is also necessary to add 100 items to the 13 “lower narrow” stones identified correctly in Area A of Hazor (Ebeling 2012).4

Yahalom-Mack described seven as “concave and slightly concave upper grinding slabs” (2007, table 11.5: from Reg. n° 791055 until the end of the table), which are in fact lower loaf-shaped stones, as is the case of one among the assemblage of the Iron Age site of Beth Shean (Yahalom-Mack & Mazar 2006, fig. 13.6:3).5 This erroneous classification led Cohen-Weinberger to the unreasonable conclusion that communal milling was carried out at Iron Age II Tel-Batash-Timnah by means of large communal slabs at three “grinding stations” (Cohen-Weinberger 2001, 228).

To summarise, the typical loaf-shaped mill, operated in tandem with a small oval handstone, existed during the Late Bronze and Iron Ages alongside less frequent larger models. It would appear that a regular use of large lower stones began in the Middle BronzeII, although an early version of a rather large oval slab, operated by a loaf-shaped handstone, appeared in the Early Bronze II (Sass 2000, fig. 12.4).

Trapezoidal sub-type

A sub-type of loaf-shaped stones characterised by trapezoid transversal and at times longitudinal sections (Fig. 9: 4, 8) is evidenced by three handstones and two slabs recovered in Stratum IV of Ein Gev dating to the Early Iron Age (11th until the first half of the 10th century BC) (Eitam 2019a, plates 3.4; 4.3). It is a type that was not common in Israel and potentially represents a foreign influence. It began to appear more regularly in the Late Bronze Age, notably at Tel Yin’am, in the form of three small trapezoidal sectioned handstones (Liebowitz 2003, fig 32: 12, 20). The type was identified at Tel Jawa as handstones reused as slabs in Iron Age I and II contexts (Daviau 2002, fig. 2.112: 3; fig. 21.14.1; fig. 21.15.1), at Tel Rehov in the Iron Age IIA (Petit 2020, fig. 7.4, 7) and Tel Miqne-Ekron in the Late Iron Age II (Milevski 2019, plates 16.2; 20.13). The spatial distribution of this subtype in the Transjordan and eastern Israel and at Tel Miqne-Ekron suggests an eastern origin.

Slab-shaped mills

The linear to and fro motion of this quern type is evidenced by linear use-wear striations on both hand and lower stones. Numerous Egyptian, Cypriot and Greek statuettes, as well as Egyptian reliefs and wooden models (all-female operators, e.g., Pritchard 1954; Tooley 1995, 28-29, fig. 19-20), depict oblong (a times loaf-shaped) handstones coupled with large flat slabs. One may challenge the suggestion that in addition to the lower working surface, the top and left and right edges of loaf-shaped handstones served for grinding (Liebowitz 2008). While this assumption finds evidence in the preparation of maize tortillas in Central America (Liebowitz 2008), local ethnographical parallels reveal the conservative nature of food preparation methods. The smooth, shiny coating often visible on the convex face and at times on the abraded pointed edges, possibly corresponds to fat residue impregnated into the stone due to contact with the human palms (Daviau 2002). This is an issue that could be clarified by chemical analyses. Natufian use-wear on the working surfaces of handstones was the object of experimentation by Laure Dubreuil (2004) who determined that the shiny polish on working surfaces of certain handstones (with ochre) resembled the use-wear of processing hide. It must be noted, however, that the differences between hide-processing use-wear and human palm stains have yet to be established (Laure Dubreuil, pers. comm.).

Symmetric (Fig. 6: 1 and Fig. 5) and asymmetric (fig. 6: 2-4 and Fig. 6) transversal sections of loaf-shaped handstones suggest two different ways of milling with large lower stones. The first is from a horizontal position, possibly on a flat floor. The miller kneels in a horizontal bent-over position with two hands driving a symmetric handstone on a slab (Pritchard 1954, fig. 149; Tooley 1995, compare fig. 19 and 20). The slab that corresponds to this position is a thin rectangular type with a rectangular section. The working face of the handstone covers the whole upper area of the slab. However, there are cases characterised by shallow lateral margins indicative of shorter handstones. This rectangular, thin shape stems from grinding with both sides of the stone (Hovers 1996) and reworking its surface. Its surface was probably dressed (pecked), as is the case of later Olynthus and rotary mills (Petit 2020, type 2a; Frankel 2003).

The second method assumes a diagonal position with the slab positioned at ca. 30-40 degrees, at times supported by a mud brick platform (Petit 2020, fig. 3-4) or on the floor. In this case, the miller crouches, presumably pushing the asymmetric, thick handstone downwards and pulling it upwards along a slanted slab (e.g., Karageorghis 2006, fig. 100). This type is at times present at Tel Dor and elsewhere and frequently is marked by a triangular lengthwise section with projecting back (Fig. 9: 7).

Grooved mills

Grooved mills characterised by a shallow longitudinal cutting on the back of their upper stones serving to lodge a rod to drive the mill are rare in Israel. Two variations are the Assyrian Type A upper stone associated with an oblong slab (Bombardieri 2010, 78-85). The two are from the sites of Tel Qasile and Tel Tannim (Avshalom-Gorni et al. 2004). Assyrian-type mills appeared in the 9th century and endured until the 5th-4th centuries BC. They were common in northern Mesopotamia (Tel Half and Nimrud) and Syria (Tel Barri and Tel Ahmar) (Alonso & Frankel 2017).

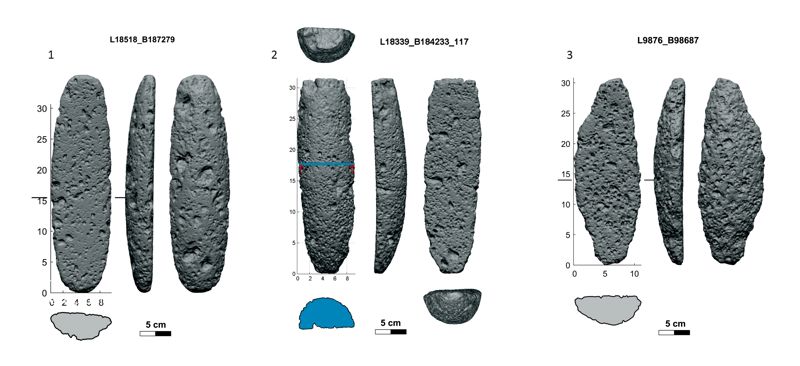

A third type of rod driven mill (Fig. 9: 8) was discovered during the excavations of Ein Gev (Eitam 2019a) led by the Japanese Mission (Eitam 2019). Although unearthed in the company of Hellenistic pottery (L. 501, B1584), it potentially dates to the Iron Age IIA. It consists of an almost complete heavy upper stone measuring 225 x 165 x 98 mm with a groove 50 mm wide and ca. 100 mm deep. The position of this cutting, along the short side of the stone, differs from the common Assyrian type. The stone is a vesicular basalt bearing straight angles and a trapezoidal section. The front external wear is fine and smooth, while the remaining is roughly pecked. It is dressed with eight deep parallel furrows (a later type of dressing that contrasts with the shallow thin striations typical of the IA period). This quern from Ein Gev resembles the Assyrian upper stones common to Mesopotamia and Syria (although the groove here is parallel to the long side). Another local case of the large, heavy, grooved loaf-shaped upper stone coupled with a rectangular oblong slab was found in levels IA II of Tel Batash.

Otherwise, a Phoenician-type mill with lateral cuttings and grips was found in Sarepta (Pritchard 1978, 88, fig. 73) and Horvat ’Ein Koveshim (Avashalom-Gorni et al. 2004). The first probably dates to the Iron Age, while the second is Hellenistic. Another version with hand-grips to be added to this group is a small grooved upper stone unearthed at Horvat ‘Ein Koveshim.

Querns produced following

an “industrial design”

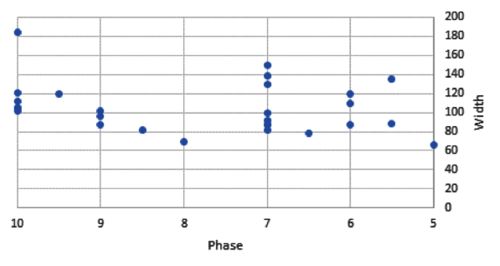

The narrow loaf-shaped handstones are characterised by pointed or rounded ends intended to facilitate the miller’s grip rendering a more efficient milling. On the other hand, the nonactive edges and base of these slabs were left roughly knapped and pecked (Fig. 8:3). The majority of loaf-shaped upper and lower stones were relatively thick and heavy (excluding those of beachrock from the Area G of Tel Dor). Their thickness was probably intended to prevent breakage. This appears to be case of certain fragmented examples, probably resulting from a reduction of their width due to intensive grinding over a long period (Fig. 8: 5-6). The width of loaf-shaped lower stones changed over time. The Late Bronze Age models were narrower than the later Iron Age I models (Liebowitz 2003, 2008). A similar trend appears at Area G of Tel Dor among the loaf-shaped handstones (28), even though those of the Late Bronze Age could not be measured. Moreover, asymmetric handstones at Tel Dor became more frequent in Iron Age I and then decrease in Iron Age II (Fig. 10). This preliminary observation requires future verification by finds from other areas of Tel Dor and elsewhere.

(Eitam, unpublished c).

Grinding stone lifespan

and patterns of use

The traditional lifespan of basalt metate handstones in Baja California and Mayan Guatemala ranges from 15 to 30 years (Aschmann 1949). This information does not appear to apply to calculating the average lifespan of Iron Age querns due to the many factors involved such as the raw material, dressing, manner of use (e.g., adding water while grinding) and grain type (Hayden 1987). The lifespan of stone tools is in fact another subject for future experimental studies in our region (Adams 1999). The data nonetheless contradicts the old view familiar to certain Israeli archaeologists claiming that querns and heavy-duty mortars served long periods. Intensive grinding led querns (and mortars) to taking on a “saddle” shape and their bases were eventually pierced or broken. Furthermore, there is evidence that handstones often break along the middle thicker point when new (Fig. 8.5), possibly due to faults in the rock.

Although dressing (pecking or furrowing) of the working surfaces improved their bite, it also shortened their lifespan. There is, nevertheless, no evidence at Tel Dor or Ein Gev of dressing. It appears that the vesicular basalt slabs coupled with porous or feldspar basalt handstones combined with the downward pressure of the miller sufficed for efficient grinding (Delgado-Raack et al. 2009). If so, the working life of the stones could have been longer as there was no loss due to dressing, even though there are a few examples of exogenous grooved handstones in Iron Age Israel. These include the Assyrian mill (with one local variant) operated with a rod and the Phoenician type with lateral handgrips (Alonso & Frankel 2017, 465). Dressing is visible on 8 to 13% of the slabs of the Iron Age II (10th-9th century BC) site of Tel Rehov (Petit, 2020). The site’s location near basalt outcrops which facilitated their replacement may explain the higher level of dressing.

There is evidence that grinning tool fragments were reused in Israel during the Iron Age II (Fig. 1.8). This observation is based on the many large handstone and slab fragments bearing secondary traces of use-wear at Iron Age Dor and other sites (Eitam, unpublished c). One may speculate that the reuse of fragments was less common in sites near the basalt outcrops such as Tel Rehov and Ein Gev, as opposed to the intensive reuse of local low-quality basalt grinder fragments in El-Ahwat. Thus, it is necessary also to consider such reused fragments when calculating the number of active querns among any stone assemblage as otherwise, the resulting spatial distribution distorts the reconstruction of human activity (Petit 2020, fig. 2; Rosenberg 2009). Although eight of the 19 fragments of Area G of Tel Dor are of a workable size and could have been reused, observing these fragments by the naked eye reveals little evidence of reuse. Only two cases at Ein Gev reveal a use-wear oriented perpendicular to the original traces (see Appendix A: oval slab B6493 and asymmetrical loaf handstone B5179-1, Eitam, in press a). It is possible that the few cases (2 of 9) are linked to the accessibility of basalt and the high economic standards of the site. The same logic appears to motivate the dressing the lower stones. Another example of the reuse of a slab fragment and handstone bears linear striations along the width of its surface varying 90 degrees from the original wear (at times identified by dark-linear marks, Eitam 2019a). These are issues that micro-use-wear analyses could resolve.

Grinding stones in their context

The quantifications of the proportion of querns in household contexts is based on spatial distribution analyses of specific mill types as well as on the seven categories of stone tools listed below. These tools form part of the category “food preparing devices”, along with mortars, massive bowls, pestles and pounders (see Appendix A). The spatial distribution of the seven categories is in line with domestic activities, whereas their ratios can shed light on certain ancient socio-economic aspects. Comparing the distribution of the groups with the spatial distribution of specific querns may shed light on their role among the different food devices and help pinpoint the location of flour making in Iron Age “kitchens”. The more common spatial distribution analyses of individual stone tools appears ineffective, as the individual items do not represent the range of domestic activities in a structure, area, or site. The weakness of this analysis is emphasised by the dull portrait of the daily life of Building 3245 at Megiddo (Rosenberg 2009) compared to a vivid picture obtained by the analysis taking into account the total material record (Gadot & Yasur-Landau 2006).

It is for this reason that the stone tools were organised into the following seven categories:

- food processing tools such as querns, mortars, large pestles, massive bowls, and spheroid pounders;

- craft tools such as abraders, pounders, small pestles, hammerstones, polishers, anvils (Fig. 1: 6) and small cupmarks;

- trade tools such as inscribed, uninscribed and archaic scale weights (Fig. 1: 3- 4; Eitam 2019a), and other stone artefacts, including storage jarcovers;

- personal belongings such as cosmetic palettes, ornaments, cosmetic bowls and rubbing stones (Eitam 2019b: pl. 1. 8-9);

- art and ritual objectssuch as figurines, sculptures, ceremonial objects, and stelae;

- industrial mechanisms suchas olive oil and wine presses, pottery wheels, and net fishing weights;

- service ware such as fine bowls and plates.

The ratios of the different groups can reflect lifestyle and standard of living in a structure, area or site, potentially shedding new light on ancient socio-economic aspects.

Conclusions

Mortars, common tools in the periods preceding the Late Bronze Age, decreased during the Iron Age. This trend may point to an extensive alteration of cereals processing in Iron Age Israel in the form of grinding and groating with querns to produce bread and groats meals, as opposed to crushing/pounding of pigments in mortars. The peeling of glume and husk cereals in mortars was not frequent in Iron Age Israel as most cultivated grains were husk free, while burley was probably consumed as groat meal of dehusked grains as oppose, for example, to the case of ancient Egypt (Eitam et al. 2015). The only Iron Age site with a relatively high quantity of mortars as opposed to querns is Khirbet Qeiyafa (11th-10th century BC). Its assemblage of 174 stone tools comprises around 55 elements of irregular querns hewn from inferior raw materials and 10 of basalt (Cohen-Klonymus 2014). Ten rough conical-concave mortars (about 15 cm in diameter and 20 cm in depth) were carved into the limestone floors of certain dwellings (Fig. 11) (pers. obs., June 2013), while 19 mobile mortars, cupmarks, and pestles were brought to light during the excavations. This untypical phenomenon, the result of limited access to basalt outcrops in eastern and northern Israel, may have stemmed from the political weakness of the newly built city in an early stage of the Judaean kingdom.

Loaf-shaped slabs operating in tandem with small handstones were Israel’s most common type of quern during the Iron Age. This mill was generally associated with the domestic sphere. On the contrary, larger grinding lower stones, frequently placed in a diagonal position and operated with heavy, asymmetric loaf-shaped handstones, were mostly linked to public buildings.

The assemblage of stone tools from Area G at Tel Dor may suggest typological changes during the Iron Age II with the appearance ofa flat, thin rectangular handstones (in both shape and section hewn from dense beachrock. Operating this tool requires less energy than the thick, dense basalt loaf-shaped handstones. This potential technological change occurred alongside the adoption of grooved and hopper mills.

Apart from the small assemblage of grooved mills, an upper stone of this type unearthed at Ein Gev bears a stark resemblance with the upper stone of an Assyrian mill from Tel Tannim in the Galilee (Avshalom-Gorni et al. 2004) and may date to the Iron Age.

Resorting to inferior raw materials at specific sites distant from basalt outcrops suggests poorer conditions stemming from a more meagre economic status (e.g., El-Ahwat) or due to questions of distance such as the case of remote border garrisons of fortified cities such as Khirbet ‘Auja el-Fuqa or the case of the hundreds of olive oil workers of Tel Miqne-Ekron. They initially resorted for these tools to chalk with local flint breccia, while at Ekron they turned to local beachrock. The residents of the upper levels of Ekron, in turn, had access to basalt (Eitam 1986) as did the Dor courthouse inhabitants from the Early Iron Age, an affluent Phoenician city that imported a variety of basalts to fit the specific needs of grinding and pounding tools.

A final note worth highlighting is that querns also took part in cultic rituals by providing flour to bake bread. This role is evidenced by the fact that the querns were intentionally broken into halves and carefully buried in ritual pits, probably avoiding the mandate defined by the sacred tools. These ritual pits were discovered at the foot of a large altar at the Early Iron Age I cultic site of Mount Ebal (Eitam, unpublished b; Zertal 1987).

Acknowledgments

The study of the stone assemblages of El-Akwat, Mount Ebal and Khirbet ‘Auja el-Fuqa’ was carried out in the framework of the Mount Menasha Project, directed by the late Prof. Adam Zertal. I thank Profs. A. Gilboa’, I. Sharon and Zorn, J.R., the excavators of Tel Dor, for the permission to study and publish part of the stone assemblage of area G. Thanks to Prof. David Sugimoto of Kioto University for permitting publishing here part of the Ein Gev stone tools report. Nevertheless, I alone am responsible for any errors in this article.

Bibliography

- Ad, A., S’abd, Al- Salam and Frankel, R. (2005): “Water Mills with Pompeian-Type Millstones at Nahal Tanninim”, Israel Exploration Journal, 55, 156-171.

- Adams, J. L. (1999): “Refocusing the Role of Food-Grinding Tools as Correlates for Subsistence Strategies in the US Southwest”. American Antiquity, 64, 475-498.

- Adams, J. L. (2013): Ground Stone Analysis. Salt Lake City: University of Utah.

- Adams, W. Y. and Adams, E. W. (1991): Archaeological Typology and Practical Reality: A Dialectical Approach to Artifact Classification and Sorting. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

- Albright, W. F. (1838): The Excavation of Tell Beit Mirsim, Vol. 2: The Bronze Age. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 17. New Haven, CT: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Alonso, N. and Frankel, R. (2017): “A Survey of Ancient Grain Milling Systems in the Mediterranean”. Revue archéologique de l’Est, supplément 43, 461-478.

- Amiran, R. (1956): “The Millstone and the Potter’s Wheel”. Eretz-Israel 4 (Ben Zvi volume), 46-49 (in Hebrew).

- Aschmann, H. (1949): “A Metate Maker of Baja, California”. American Anthropologist 51, 682-686.

- Avitzur, S. (1972): Daily Life in Eretz Israel in the XIX Century. Am Hasefer (in Hebrew).

- Avshalom-Gorni, D., Frankel, R. and Getzov, N. (2004): “Grooved Upper Grinding Stones of Saddle Querns in Israel”, Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, 31, Issue 2, 262-267.

- Baysal, A. and Wright, K. I. (2002): “Analysis of Ground Stone Artefacts from the Excavations of 1995-1999”. Catalhoyuk Website Archive Report. http://www.catalhoyuk.com/archive_reports/2002/ar02_10.html

- Ben-Ami, D. (2005a): “Miscellaneous Small Objects”, in: Ben-Tor, A. Zarzecki-Peleg, A. & Cohen-Anidjar, S. (eds), Yoqneʿam II: The Iron Age and the Persian Period. Final Report of the Archaeological Excavations (1977-1988), Qedem Reports 6. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 377-394.

- Ben-Ami, D. (2005b): “Stone Objects”, in: Ben-Tor, A., Ben-Ami, D., Livneh, A. (eds), Yoqneʿam III: The Middle and Late Bronze Ages, Qedem Reports 7. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 363-369.

- Ben-Tor, A. (1987): “The Small Finds,” in: Ben Tor, A, Portugali, Y. (eds), Tel Qiri: A Village in the Jezreel Valley. Report of the Archaeological Excavations 1975-1977, Qedem 24. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 236-243.

- Bennett, C.-M. and Bienkowski, P. (1995): Excavations at Tawilan in Southern Jordan. British Academy Monographs in Archaeology 8, Oxford.

- Bombardieri, L. (2005): “The Millstones and Diffusion of New Grinding Techniques from Assyrian Mesopotamia to the Eastern Mediterranean Basin during the Iron Age”, in: Monozzi, O., Di Marzio, M.L. & Fossataro, D. (eds), Proceedings of the IX Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology, Chieti, Oxford, 487-494.

- Cato (1936): M. P. Cato, On Agriculture, Chapters I-CLXII, trans. Hooper, W. D. and rev. Ash, H. B. The Loeb Classical Library 283. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

- Childe, V. G. (1943): “Rotary Querns on the Continent and in the Mediterranean Basin”. Antiquity 17, 19-26.

- Cohen Kolonymus, H. (2014): The Iron Age Groundstone Tools Assemblage of Khirbet Qeiyafa: Typology, Spatial Analysis and Sociological Aspects. MA Thesis, Jerusalem: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Cohen-Weinberger, A. (2001): “The Ground Stone,” in: Mazar A. & Panitz-Cohen, N. (eds), Timnah (Tel Batash) II: The Finds from the First Millennium BCE, Qedem 42. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 225-237.

- Dalman, G. (1933): Arbeit und Sitte in Palästina, Vol. 3: Von der Ernte zum Mehl. Beiträgezur Förderung christlicher Theologie, 2nd series, Sammlung wissenschaftlicher Monographien, 29. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann.

- Daviau, P. M. M. (2002): Excavations at Tall Jawa, Jordan, Vol. 2: The Iron Age Artefacts. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 11/2. Leiden: Brill.

- Delgado-Raack, S., Gomez-Gras and D., Risch, R. (2009): “The Mechanical Properties of Macrolithic Artifacts: a Methodological Background of Functional Analysis”, Journal of Archaeological Science, 39, 9, 1823-1831.

- Dubreuil, L. (2002): Etude fonctionnelle des outils de broyage natoufiens: nouvelles perspectives sur l’émergence de l’agriculture au Proche-Orient. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Université de Bordeaux 1.

- Dubreuil, L. (2004): “Long-Term Trends in Natufian Subsistence: A Use-Wear Analysis of Ground Stone Tools”. Journal of Archaeological Science, 31, 1613-1629.

- Dubreuil, L. (2008): “Mortar versus grinding slabs function in the context of the Neolithization process in the Near East”, in: L. Longo (ed.) ‘Prehistoric technology’ 40 years later: functional analysis and the Russian legacy: 169-177. Verona: Museo Civico di Verona and Universita degli Studi di Verona.

- Dubreuil, L. and Grosman, L. (2009): “Ochre and Hide-working at a Natufian Burial Place”, Antiquity, 83, 935-954.

- Ebeling J. R. (2012): “Ground Stone Artifacts”, in: Ben-Tor, A., Ben-Ami, D. & Sandhaus, D. (eds), Hazor VI: The 1990-2009 Excavations, The Iron Age, Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and the Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 542-558.

- Ebeling, J. R. and Rowan, Y. M. (2004): “The Archaeology of the Daily Grind: Ground Stone Tools and Food Production in the Southern Levant”, Near Eastern Archaeology, 67, 108-117.

- Eitam, D. (1980): The Production of Oil and Wine in Mt. Ephraim in the Iron Age. M.A. thesis, Tel Aviv University (in Hebrew).

- Eitam, D. (1996): “The Olive Oil Industry at Tel Miqne-Ekron in the Late Iron Age”, in: Eitam, D. & Heltzer, M. (eds), Olive Oil in Antiquity: Israel and Neighboring Countries from the Neolithic to the Early Arab Period, History of the Ancient Near East Studies 7. Padova: Sargon, 167-196.

- Eitam, D. (unpublished a): “The Ground Stone Tools of El-Ahwat”, University of Haifa.

- Eitam, D. (unpublished b): “The Ground Stone Tools of Mount Ebal”, University of Haifa.

- Eitam, D. (unpublished c): “The Stone Tools of Tel Dor, Area G”.

- Eitam, D. (2005): “The Food Preparation Installations and the Ground Stone Tools”, in: Zertal, A. (ed.), The Manasseh Hill Country Survey, Vol. 4: From Nahal Bezek to the Sartaba, Haifa: Haifa University and the Ministry of Defense (in Hebrew), 648-723.

- Eitam, D. (2007): “The Stone Tools from Khirbet ‘Aujah el-Foqa’”, in: Crawford, S. W., Ben-Tor, A., Dessel, J. P., Dever, W., Mazar, A. & Aviram, J. (eds), Up to the Gates of Ekron: Essays on the Archaeology and History of the Eastern Mediterranean in Honor of Seymour Gitin, Jerusalem: W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research and Israel, 93-100.

- Eitam, D. (2009a): “Late Epipaleolithic rock-cut installations and ground stone tools in the Southern Levant: Methodology and typology”, Paléorient 31, 77-104.

- Eitam, D. (2009b): “Cereal in the Ghassulian culture in central Israel: grinding installation as a case study”, Israel Exploration Journal 59/1, 63-79.

- Eitam, D. (2013): Archaeo-Industry of the Natufian Culture: Late Epipaleolithic Rock Cut Installations and Ground Stone Tools in the Southern Levant. PhD dissertation, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem (in Hebrew).

- Eitam, D., Kislev, M., Karty, A. & Bar-Yosef, O. (2015): “Experimental Barley Flour Production in 12,500-Year-Old Rock-Cut Mortars in Southwestern Asia”. PLoS ONE 10.7: e0133306.

- Eitam, D. and Schoenwetter, J. (2020): Feeding the living, feeding the dead: Natufian low-level food production societies in the Southern Levant (15,000-11,500 Cal BP) Mitekufat Haeven: Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society 50, 44-78.

- Eitam, D. (2019a): “Stone Tools of the Iron Age Ein Gev and their Implication, The Japanese Excavation Project”, in: Squitieri, A. & Eitam, D. (eds), Stone tools in Ancient Near East and Egypt. Ground stone tools and rock-cut installations from Late Epipaleolithic to Late Antiquity (Near Eastern Archaeology 4). Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology, 278-298.

- Eitam, D. (2019b): “Cuboid-Spheroid Stone Object – an Archaic Scale Weight – Public Weighing-Systems in Iron Age Israel,” in: Squitieri, A. & Eitam, D. (eds), Stone tools in Ancient Near East and Egypt. Ground stone tools and rock-cut installations from Late Epipaleolithic to Late Antiquity (Near Eastern Archaeology 4). Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology, 179-188.

- Eitam, D. (in press a): “Catalogue of the Stone Tools from Area G”, Excavations at Dor, Final Report, Qedem Reports. Jerusalem: The Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Israel Exploration Society.

- Eitam, D. (in press b): “Chapter IV/1: Stone Tools”, in: Sugimoto, D. T. (ed.), ‘En Gev on the Eastern Shore of the Sea of Galilee: Report of the Archaeological Excavations (1998–2004). Keio University.

- Elliott, C. (1991): “The Ground Stone Industry”, in: Yon, M (ed.), Ras Shamra-Ougarit VI: Art et industries de la pierre, Paris: Éditions recherche sur les civilisations, 9-99

- Frankel, R. (1999): Wine and Oil Production in Antiquity in Israel and other Mediterranean Countries. JSOT/ASOR Monograph Series 10, Sheffield.

- Frankel, R. (2003): “The Olynthus Mill, Its Origin and Diffusion: Typology and Distribution”, American Journal of Archaeology, 107, 1-21.

- Gadot, Y. and Yasur-Landau, A. (2006): “Beyond Finds: Reconstructing Life in the Courtyard Building of Level K-4”, in: Finkelstein, I., Ussishkin, D & Halpern B. (eds), Megiddo IV: The 1998-2002 Seasons, 2 vols. Monograph Series of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology 24. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, 583-600.

- Gilboa, A., Sharon, I. & Zorn, J. R. (2014): “An Iron Age I Canaanite/Phoenician Courtyard House at Tel Dor: A Comparative Architectural and Functional Analysis”, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 372, 39-80.

- Hayden, B. (1987): “Traditional Metate Manufacturing in Guatemala Using Chipped Stone Tools”, in: Hayden, B (ed.), Lithic Studies Among the Contemporary Highland Maya, Tucson: University of Arizona, 8-119.

- Hillman, G. C. (1984): “Traditional husbandry and processing of archaic cereals in recent times: part I, the glume-wheats”, Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture, I, 131-152.

- Hillman, G. C. (1985): “Traditional husbandry and processing of archaic cereals in recent times, part II: the free-threshing wheats”, Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture, II, 1-31.

- Hovers, E. (1996): “The Groundstone Industry”, in: Ariel, D.T. & De Groot, A. (eds), Excavations in the City of David 1978–1985 Directed by Yigal Shiloh, Vol. 4: Various Reports, Qedem 35. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 171-192.

- Kraybill, N. (1977): “Pre-Agricultural Tools for the Preparation of Foods in the Old World”, in: C. A. Reed, (ed.), World Anthropology. The Hague and Paris: Mouton, 485-521.

- Lewis, M. J. T. (1997): Millstone and Hammer – The Origin of Water Power, Hull: University of Hull Press.

- Liebowitz, H. A. (2003): Tel Yin’am I: The Late Bronze Age. Excavations at Tel Yin’am, 1975-1989, Studies in Archaeology, 42. Austin: Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory, University of Texas at Austin.

- Liebowitz, H. A. (2008): “Wear Patterns on Ground Stone Implements from Tel Yin’am”, in: Rowan, Y. M. & Ebeling, J. R. (eds), New Approaches to Old Stones: Recent Studies of Ground Stone Artifacts London and Oakville: Equinox, 182-195.

- Macalister, R. A. S. (1912): Excavation of Gezer, 1902‒1905 and 1907‒1909, Vol. 1. London: Murray.

- Milevski, I. (1998): “The Ground Stone Tools”, in: Edelstein, G., Milevski, I. & Durant, S. (eds), Villages, Terraces, and Stone Mounds: Excavations at Manahat, Jerusalem, 1987-1989, Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 3. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 182-195.

- Milevski, I. (2019): “The stone tools and vessels from Tel Miqne-Ekron: a report on the Bronze and Iron Ages”, in: Squitieri, A. & Eitam, D. (eds), Stone tools in Ancient Near East and Egypt, Ground stone tools and rock-cut installations from Late Epipaleolithic to Late Antiquity (Near Eastern Archaeology 4). Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology, 305-344.

- Petit, L. P. (2020): “Chapter 43: The Grinding Stones”, in: Mazar, A. & Panitz Cohen, N. (eds), Excavations at Tel Rehov Vol. V: Various Objects and Natural-Science Studies, Qedem 63. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Pliny (1938-1962): Pliny, Naturalis Historiae, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 37 books in 10 volumes, 1938-1962.

- Postgate, J. N. (1984): “Processing of Cereals in the Cuneiform Record”, Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture, 1, 103-113.

- Pritchard, J. B. (1954): The Ancient Near East in Pictures Relating to the Old Testament. Princeton.

- Pritchard, J. B. (1978): Recovering Sarepta. A Phoenician City. Princeton.

- Rosenberg, D. (2009): “Spatial Distribution of Food Processing Activities at Late Iron I Megiddo”, Tel Aviv, 35: 96-113.

- Rosenberg, D. (2013): “The Groundstone Assemblage”, in: Finkelstein, I., Ussishkin, D. & Cline, E. H. (eds), Megiddo V, The 2004‒2008 Seasons, Vol. III, Monograph Series of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology 31. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, 930-976.

- Samuel, D. (1999): “Bread Making and Social Interactions at the Amarna Workmen’s Village. Egypt”, World Archaeology, 31, 121-44.

- Sass, B. (2000): “The Small Finds” in: Finkelstein, I, Ussishkin, D. & Halpern, B. (eds), Megiddo III: The 1992‒1996 Seasons, Vol. 2, Monograph Series of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology 18. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, 349-428.

- Sass, B. (2004): “Pre-Bronze Age and Bronze Age Artefacts. Section A: Vessels, Tools, Personal Objects, Figurative Art and Varia”, in: Ussishkin, D. (ed.), The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973-1994), Vol. 3, Monograph Series of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology 22. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, 1405-1524.

- Sass, D.and Cinamon, G. (2006): “The Small Finds”, in: Finkelstein, I, Ussishkin, D. & Halpern, B., (eds), Megiddo IV: The 1998-2002 Seasons, Vol. 1. Monograph Series of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology 24. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, 353-436.

- Sass, B. and Ussishkin, D. (2004): “Iron Age and Post-Iron Age Artefacts. Section A: Vessels, Tools, Personal Objects, Figurative Art and Varia”, in: Ussishkin, D. (ed.), The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973‒1994), Vol. 4, Monograph Series of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology 22. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, 1983-2057.

- Segev, A. and Sass, E. (2009): The Geology of the Carmel Region. Albian-Turonian volcano–sedimentary cycles on the Northwestern Edge of the Arabian Platform. Report GSI/7/2009. Jerusalem: The Geological Survey of Israel. (in Hebrew).

- Squitieri, A. and Eitam, D. (eds) (2019): Stone tools in Ancient Near East and Egypt ground stone tools and rock-cut installations from Late Epipaleolithic to Late Antiquity, (Near Eastern Archaeology, 4). Oxford, Archaeopress Archaeology.

- Sugimoto, D.T. (2015): “History and Nature of Iron Age Cities in the Northeastern Sea of Galilee Region: A Preliminary Overview”, Orient, 50, 91-108.

- Stroulia, A. Dubreuil, L., Robitaille, J., Nelson, K. (2017): “Salt, Sand, and Saddles: Exploring an Intriguing Work Face Configuration among Grinding Tools”, Ethnoarchaeology, DOI: 10.1080/19442890.2017.1364053.

- Tooley, A. M. J. (1995): Egyptian Models and Scenes, Shire Egyptology, 22, Princes Risborough: Shire.

- Turkowski, L. (1996): “Peasant Agriculture in the Judean Hills”, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 101, 101-13.

- Varro, M. T. (1936): On Agriculture, Books I-III, trans. Hooper, W. D. and rev. Ash, H. B. The Loeb Classical Library 283. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

- Wilson, H. (1988): “Egyptian Food and Drink”, Shire Egyptology, 9. Princes Risborough: Shire.

- Wright, K., (1991): “The origins and development of ground stone assemblages in late Pleistocene southwest Asia”, Paléorient, 17(1), 19-45.

- Wright, K. (1992): “A Classification System for Ground Stone Tools from the Prehistoric Levant”, Paléorient 18.2, 53-81.

- Yadin, Y., Aharoni, Y., Amiran, R., Dothan, T., Dunayevsky, I. and Perrot, J. (1958): Hazor I: An Account of the First Season of Excavations, 1955. Jerusalem: Magnes.

- Yadin, Y., Aharoni, Y., Amiran, R., Dothan, T., Dunayevsky, I., Perrot, J. (1960): Hazor II: An Account of the Second Season of Excavations, 1956. Jerusalem: Magnes.

- Yadin, Y., Aharoni, Y., Amiran, R., Dothan, M., Dothan, T., Dunayevsky, I., Perrot, J. (1961): Hazor III-IV: An Account of the Third and Fourth Seasons of Excavations, 1957-1958, Plates. Jerusalem: Magnes.

- Yadin, Y., Geva, S. (1986): Investigations at Tel Beth-Shean: The Early Iron Age Strata, Qedem, 23. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Yahalom-Mack, N. (2006): “Groundstone Industry”, in: Panitz-Cohen, N. & Mazar, A. (eds), Timnah (Tel Batash) III: The Finds from the Second Millennium BCE, Qedem, 45. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Jerusalem, 267-274.

- Yahalom-Mack, N. (2007): “The Groundstone Tools and Objects”, in: Mazar, A. & Mullins, R. A. (eds), Excavations at Tel Beth Shean 1989‒1996, Vol. 2, The Middle and Late Bronze Age Strata in Area R., Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University, 626-638.

- Yahalom-Mack, N., Mazar, A. (2007): “Various Finds from the Iron Age II Strata in Areas P and S”, in: Mazar, A. (ed.), Excavations at Tel Beth-Shean 1989‒1996, Vol. 1, From the Late Bronze Age IIB to the Medieval Period, Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University in Jerusalem, 468-504.

- Zertal, A. (1987): “An Early Iron Age Cultic Site on Mount Ebal: Excavation Seasons 1982-1987”, Tel Aviv, 14-14 (2), 105-160.

Appendix A

| Locus | Basket | Stratum | Description | Interior measure | Working face section | Exterior measure | Preservation | Rock formation | Figure3 | Notes | ||||||||

| Type | Sub-type | Upper axis 1 | Upper axis 2 | Length | Lower wear | Longwise section | Lateral section | 1 Axis | Axis 2 | Length | Weight | |||||||

| Tel | Dor | area | G | |||||||||||||||

| 9025 | 90985 | 1a | Grinding slab | complete | Basalt | Stone not found | ||||||||||||

| 9037 | 90543 | 1 | Grinding slab | loaf | coarse abraded | S concave | S convex | 120 | 58 | Porous basalt | Heavy | |||||||

| 9249 | 92633 | 1b | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded | convex | S convex | 240(300) | 110 | 40 | Porous basalt | Symmetric | ||||||

| 9298 | 96447 | 5 / 6 ? | Grinding slab | Not identical | concave | concave | fragment | Basalt | St not found | |||||||||

| 9305 | 92732 | 6a | Grinding slab | slab | V fine abraded | S concave | S concave | 71 | 55 | 29 | fragment | Feldspar basalt | Symmetric | |||||

| 9328 | 9?952 | 6a | Handstone | rectangular | fine abraded | De concave | De concave | -110 | 93 | 50 | Feldspar basalt | |||||||

| 9380 | 93779 | 7 | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded&smooth end | S convex | S convex | 165(240) | 150 | 51 | Porous basalt | Symmetric | ||||||

| 9390 | 937790 | 0 | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded | S convex | convex | 175(250) | 100 | 30 | Porous basalt | Symmetric | ||||||

| 9472 | 94413 | 2 b | Grinding slab | loaf | fine abraded | V S concave | V S concave | 320 | 137 | 48 | 375 | Porous Basalt | ||||||

| 9515 | 182865 | 1 | Handstone | loaf | coarse abraded | S convex | S convex | 123(190) | 86 | 45 | Porous basalt | Ass-L section | ||||||

| 9607 | 96543 | Clean locus | HS oval | 150 | 98 | 44 | Calcareous flint | |||||||||||

| 9631 | 96178 | 5 ? | Handstone | loaf ? | V fine abraded | convex | concave | 120 | 66 | 38 | fragment | Vesicular basalt | St not found | |||||

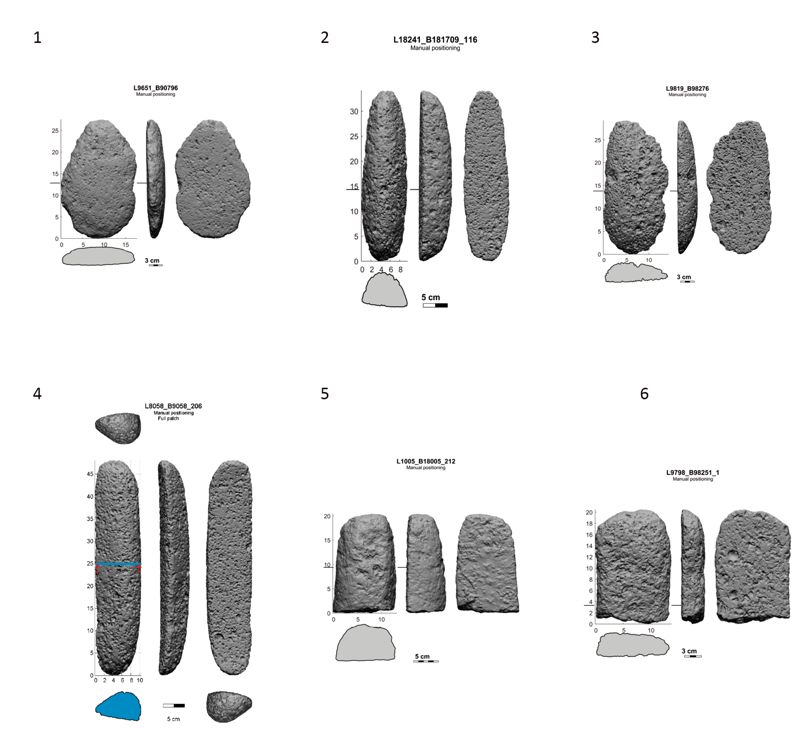

| 9651 | 90796 | 4 | Handstone | oval | coarse abraded | S convex | flat | 270 | 175 | 62 | complete | Vesicular basalt | Fig. 6:1 | Symmetric | ||||

| 9671 | 96985 | 6 | Grinding slab | loaf | fine abraded | S concave | S convex | 130(330) | 150 | 49 | Porous basalt | Symmetric | ||||||

| 9679 | 96718 | Grinding slab | slab | V fine abraded | S concave | flat | 400 | 86 | 66 | 300 | Feldspar basalt | |||||||

| 9679 | 96782 / 2 | 6a | Grinding slab | slab | X fine abraded | 350 | 240 | 62,5 | 280 | Feldspar basalt | Thick | |||||||

| 9679 | 96985 | 6a | Grinding slab | slab | V fine abraded | flat | flat | 145(400) | 80 | 62 | 35 | Porous basalt | ||||||

| 9679 | 96782 | 6a | Handstone | V fine abraded | convex | 350 | 240 | 62,5 | 250 | Feldspar basalt | Asymmetric | |||||||

| 9679 | 96782 / 1 | 6a | Handstone | loaf / abrader/ grinding slab | carved | concave | concave | 260 | 120 | 96 | fragment | Hard limestone | R-concave | |||||

| 9679 | 96782 / 3 | 6a | Handstone | irregular | fine carved | S concave | S concave | -140 | 65 | 47,5 | fragment | Kurkar | ||||||

| 9684 | 97785 | 5 ? 6-9 | Grinding slab | loaf | 160 | 76 | 36 | fragment | Soft limestone | Reused handstone ? | ||||||||

| 9684 | 97785 | 5 ? 6-9 | Grinding slab | loaf | 160 | 76 | 36 | fragment | Soft limestone | Reused handstone ? | ||||||||

| 9691 | 96797 | Clean locus | Handstone | loaf | V fine abraded | flat | flat | 120(250) | 110 | 45 | Porous basalt | Asymmetric | ||||||

| 9703 | ? | 7 d | Grinding slab | slab | fine abraded | concave | flat | 253(320) | 245 | 43 | 250 | |||||||

| 9712 | 97005 | 5 / 6a? | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded | V S convex | S convex | 70(200) | 87 | 34 | Vesicular basalt | Asymmetric | ||||||

| 9722 | 97086 | 6 b | Handstone | loaf/ Symmetric | fine abraded | De concave | flat | 230 | 87 | 50 | Porous basalt | smoothed by hands | ||||||

| 9733 | 97140 | Clean locus | Grinding slab | loaf | fine abraded | S concave | flat | 244(350) | 125 | 42 | Porous basalt | flat bottom | ||||||

| 9788 | 87873/1 | 4/5! | Grinding slab | loaf | concave | flat or S convex | 110(350) | 140 | 36 | Basalt | Symmetric | |||||||

| 9788 | 97873/2 | 5/4! | Handstone | oval | fine abraded | flat | fault | 110(160) | 90 | 45 | 130 | Porous basalt | Asymmetric / | |||||

| 9796 | 98064 | 4/5? | Grinding slab | slab | fine abraded | concave | S convex | 250(300) | 140 | 60 | Porous basalt | |||||||

| 9798 | 98068 | 5 | Grinding slab | slab | V fine abraded | S concave | fault | 150(270) | 85 | 34 | 250 | Porous basalt | ||||||

| 9798 | 98259/1 | 5? | Handstone | loaf | coarse abraded&fine abraded | concave | S convex | 170(280) | 135 | 30 | fragment | Beachrock | Fig. 6:6 | Asymmetric tool with shells. | ||||

| 9819 | 98276 | 7a | Handstone | oval | fine abraded | flat | flat | 289 | 139 | 44 | Hard limestone | Fig. 6:3 | Oval | |||||

| 9814 | 7a | Handstone | loaf / Grinding slab | fine abraded | flat | S convex | 100(180) | 95 | 55 | fragment | Porous basalt | Symmetric | ||||||

| 9816 | 99035 | 7 | Grinding slab | slab or irregular loaf | fine abraded | S concave | flat | 250 | 175 | 98,5 | fragment | Porous basalt | ||||||

| 9816 | 99080 | 7 | Grinding slab | slab | abraded | S concave | Plato | 110(400) | 940 | 55 | 300 | Vesicular basalt | ||||||

| 9816 | 99235 | 7 | Grinding slab | slab | fine abraded | flat | S convex | 353 | 385 | 53 | 386 | Feldspar basalt | ||||||

| 9850 | 98527 | 7a/6 | Handstone | oval | fine abraded | S convex | S convex | 100(170) | 90 | 47 | Porous basalt | |||||||

| 9874 | 98654 | 7a?/6? | Grinding slab | slab | 150(350) | 90 | 44 | 300 | Basalt | |||||||||

| 9894 | 98938 | 7 ?/6? | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded | flat | concave | 120 | 78 | 36 | vesicular basalt | St not found | ||||||

| 9895 | 99319 | 7 ?/6? | Handstone | loaf ? | V fine abraded-L fine abraded-Midd coarse abraded-L | concave | S concave | fragment | Vesicular basalt | St not found | ||||||||

| 9903 | 99570 | 8 | Grinding slab | slab or oval | fine abraded | flat | flat | 250 | 102,5 | 49 | fragment | Feldspar basalt | Well eroded | |||||

| 9932 | 99579 | 6a | Grinding slab | slab | ? | convex | 230 | 132 | 34 | 170 | Limestone | |||||||

| 9937 | 99571/1 | 7 | Grinding slab | slab or oval | fine abraded | concave | flat | 230(240) | 155 | 48 | 200 | fragment | Porous basalt | Point end | ||||

| 9937 | 99738 | 7 | Grinding slab? | fine abraded | Irr flat | Irr flat | -350 | 119 | 39 | fragment | basalt | |||||||

| 9937 | 99571 | 7 | Grinding slab | Non identical | fine abraded | flat | flat | 48 | 33 | 20 | Feldspar basalt | Pointed edge in T-sec | ||||||

| 9945 | 99552 | 7 | Grinding slab | loaf | fine abraded | S convex | S convex | 225(300) | 114 | 48 | Porous basalt | Convex sec due to crispy Nat | ||||||

| 9949 | 99666 | 7 | Handstone | loaf | V fine abraded | convex | convex | 180 | 82 | 48 | Vesicular basalt | |||||||

| 9950 | 99689 / 1 | 7 | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded & coarse abraded | S convex | S concave | 200 | 99 | 50 | Vesicular basalt | |||||||

| 9950 | 99689 / 2 | 7 | Handstone | loaf | fine&coarse abraded | V S concave | V S concave | 160 | 900 | 50 | Feldspar basalt | Asymmetric T-sec | ||||||

| 9950 | 99693 | 7 | Handstone | loaf/ symmetrical | fine abraded | S convex | S convex | 80(250) | 87 | 50 | Vesicular basalt | for better hold | ||||||

| 9963 | 181704 | 7 | Handstone | oval | fine abraded | S convex | flat | 220 | 128 | 101 | Feldspar basalt | Asymmetric T-sec | ||||||

| 9982 | 181516 | 9 | Grinding slab | slab or oval / Grinding slab | abraded | flat | S convex | 300 | 103 | 47 | 280 | fragment | Porous basalt | Thick | ||||

| 9985 | 160070 | 9 | Handstone | loaf/ Grinding slab | slab | fine abraded | flat | S convex | 180 | 82 | 56,5 | 86 | fragment | Vesicular Basalt | Asymmetric T-sec | |||

| 9986 | 160026 | 6 b | Grinding slab | slab / slab ? | V fine abraded/coarse abraded | V S concave | flat | 440(460) | 270 | 41 | 280 | fragment | Porous basalt | |||||

| 9987 | 160058 | 7 | Handstone | loaf / Grinding slab | fine abraded | S concave | flat | 280 | 92 | 55 | fragment | Porous basalt | Reused | |||||

| 9994 | 160145 | 7 | Grinding slab | slab | fine abraded | S concave | flat | 350 | 105 | 36 | 350 | Feldspar basalt | ||||||

| 18005 | 180032 | 6 | handstone | loaf | No use-wear | flat | flat | 200 | 126,5 | 80 | fragment | Kurkar | Fig. 6:5 | Not used tool. | ||||

| 18058 | 181326 | 9 or 8? | Grinding slab | slab | fine abraded | S concave | V S convex | 400 | 81 | 56 | 300 | Vesicular basalt | ||||||

| 18058 | 181310 | 9 | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded | flat/S convex ends | S convex | 475 | 102 | 65,5 | complete | Basalt | Fig. 6:4 | Very long loaf handstone, probably overlap slab width. | ||||

| 18058 | 181309 | 9 or 8? | Handstone | oval ? | fine abraded | flat | S convex | fragment | Feldspar basalt | In Museum | ||||||||

| 18069 | 181031 | 9 | abrader | Non identical | 84 | 66 | 41 | fragment | Feldspar basalt | Burned St | ||||||||

| 18074 | 181075 | 6 b | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded/ coarse abraded | flat | flat | 120(220) | 110 | 84 | fragment | Porous basalt | half tool | |||||

| 18074 | 181074 | 6 b | Handstone | HS Sm | fine abraded | flat | flat | 82 | 44 | 34 | Soft limestone | Fig. 5:2 | ||||||

| 18086 | 181295 | 10 b -10c? | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded | flat | flat | 113(220) | 102 | 60 | Vesicular basalt | Asymmetric T-sec | ||||||

| 18090 | 181399 | 9 | Grinding slab | Not identical | fine abraded | S convex | S convex | Soft limestone | St not found | |||||||||

| 18221 | 181550 / 1 | 10 a | Grinding slab? | 300 | 240 | 40 | 250 | fragment | Soft limestone | Reused | ||||||||

| 18221 | 181550 / 2 | 10 a | Grinding slab | slab / abrader slab | 300 | 240 | 40 | 250 | Hard limestone | Top and front- pecked& abraded | ||||||||

| 18221 | 181551 | 10 a | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded | flat | flat | 104(230) | 105 | 48 | Porous basalt | Asymmetric T-sec | ||||||

| 18223 | 182667 | 6 a/5? | Handstone | loaf / Grinding slab | V fine abraded | flat | flat | 119(200) | 88 | 47 | fragment | Porous basalt | Reused | |||||

| 18229 | 186021 | 10 | Grinding slab | Not identical | fragment | Hard limestone | St not found | |||||||||||

| 18240 | 18?670 | 9 | Grinding slab | Not identical | fragment | Hard limestone | ||||||||||||

| 18241 | 181702 / 1 | 9 | Grinding slab | slab or oval | 245 | 119 | 63 | 160 | fragment | Hard limestone | ||||||||

| 18241 | 181702 / 2 | 9 | Grinding slab | slab | 350 | 163 | 54 | 200 | Hard limestone | |||||||||

| 18241 | 181709 | 9 | Handstone | loaf | 345 | 96 | 65 | Calcareous flint | Fig. 6:2 | Industrial design | ||||||||

| 18252 | 181743 | 10 | Grinding slab | slab | fine abraded | S concave | flat | 140(280) | 106 | 33 | 190 | Vesicular Basalt | ||||||

| 18313 | 184017 | 10 b -10c? | Handstone | loaf symmetrical | polish | convex | flat | 56 | 56 | 38 | Beachrock ? | Pebble | ||||||

| 18316 | 183796 | 10 b | Grinding slab | Not identical/ palette? | fine abraded | convex/concave | convex/concave | 65(130) | 62 | 32 | Feldspar basalt | bifacial tool | ||||||

| 18322 | 18?818 | 10 | Grinding slab | oval symmetrical | polish | S convex | S convex | 230 | 93 | 45 | 190 | fragment | Porous basalt | |||||

| 18322 | 10c | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded | flat | flat | 68(220) | 90 | 44 | 120 | fragment | Feldspar basalt | ||||||

| 18323 | 183981 | 10 | Grinding slab | Not identical | shine | flat | flat | fragment | Limestone | St not found | ||||||||

| 18331 | 184284 | 10 | Handstone | loaf | polish | S convex | S convex | 220 | 105 | 51 | Basalt | |||||||

| 18333 | 181588 | 10 c | Handstone | loaf / Grinding slab | polish | Irr | Irr | 250 | 184 | 43 | fragment | Basalt | Reused | |||||

| 18334 | 184136 | 11 / 10c | Grinding slab | Grinding slab | fine abraded | S convex | flat | 86 | 58 | 39 | fragment | Basalt | ||||||

| 18334 | 184129 | 11 / 10c | Grinding slab | Not identical / handstone/ abrader | 77 | 50 | 25 | fragment | limestone | Fig. 5:1 | Symmetric | |||||||

| 18335 | 184321 | 10 c | Handstone | oval | polish+linear striae | flat | flat | 110 | 63 | 32 | Feldspar basalt | |||||||

| 18339 | 184233 | 9 | Grinding slab | loaf | polish | flat | Flat (F) | 290 | 85 | 5 | Soft limestone | |||||||

| 18339 | 184232 | 9 | Handstone | loaf | polish | flat | flat | 300 | 120 | 88 | Hard limestone | Fine abraded on L | ||||||

| 18344 | 184091 | 10 | Handstone | HS loaf / abraded slab | polish | S convex | S convex | 200 | 121 | 68 | fragment | Basalt | Reused | |||||

| 18350 | 184562 | 11 / 10c | Grinding slab | Not identical | fine abraded | flat | flat | 75 | 42 | fragment | Hard limestone | |||||||

| 18355 | 182199 | 10 c | Handstone | loaf | coarse abraded | flat | S convex | 48(280) | 112 | 60 | Porous basalt | Asymmetric T-sec | ||||||

| 18364 | 181514 | 7 | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded | flat | flat | Feldspar basalt | St not found | |||||||||

| 18370 | 185121 | 9 | Grinding slab | slab or oval | concave | S concave – due to change direction in 2nd use | 112(300) | 137 | 61 | 210 | fragment | Porous basalt | Reused | |||||

| 18374 | 185164 | 10 c | Grinding slab | Not identical | fragment | Limestone | St not found | |||||||||||

| 18374 | 185265 / 2 | 10 c | Handstone | loaf | long carried | 70 | 50 | Basalt | St not found | |||||||||

| 18378 | 185239 | 11 | Handstone | loaf? | fragment | Basalt | St not found | |||||||||||

| 18392 | 185446 | 12a | Handstone | loaf | Basalt | St not found | ||||||||||||

| 18411 | 185977 | 11 b | Grinding slab | slab ?/ not identical | 91 | 85 | fragment | Basalt | Reused | |||||||||

| 18443 | 186292 | 11 | Grinding slab | slab or oval | V smooth | 300(350) | 170 | 39 | 205 | fragment | Porous basalt | |||||||

| 18455 | 186813 | 11 b | Grinding slab | loaf | fine abraded | V S concave | flat | 205(300) | 129 | 53 | Feldspar basalt | |||||||

| 18496 | 187140 | 11 | Grinding slab | slab or oval | 200 | 106,5 | 39 | 130 | fragment | Basalt | Thin tool | |||||||

| 18518 | 187279 | 9 b | Grinding slab | loaf | 350 | 99 | 49 | Feldspar basalt | Curved striae along axle | |||||||||

| 18564 | 188335 | 8 | Handstone | loaf | coarse abraded/fine abraded | flat | flat | 94(170) | 69 | 45 | Feldspar basalt | Asymmetric T-sec | ||||||

| 18564 | 1883345 | 8 c | Handstone | loaf | flat | flat | 170 | 64 | 44 | 69 | Basalt | for better hold | ||||||

| 18570 | 188445 | 9 | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded | flat | S convex | 300 | 87 | 53 | Porous basalt | Asymmetric T-sec | ||||||

| 18570 | 188440 | 9 | Handstone | oval / handstone | 130 | 88 | 52 | fragment | Basalt | Pec on breaks | ||||||||

| ? | 181099 | Grinding slab | slab | 290 | 140 | 41 | 220 | Basalt? | fine abraded on T | |||||||||

| ? | 92327 | Handstone | loaf | fine abraded+V fine abraded | flat | flat | 150(300) | 115 | 41 | Porous basalt | Asymmetric | |||||||

| 18 0/2 32 | 184198 | 9 | Handstone | loaf | Vesicular basalt | St not found | ||||||||||||

| 9049 ? | 90403 or 9 ? | 1 b? | Grinding slab | Not identical | fragment | Basalt | St not found | |||||||||||

| 9561 ? | 94697? | 1? | Handstone | loaf symmetrical | fine abraded | concave | concave | 120 | 76 | 36,5 | 83 | Flint pebble | Multi-facial | |||||

| 974/16 | 98032 | 2 ? | Grinding slab | slab | 240 | 155 | 41 | 190 | Limestone | |||||||||

| 97503 ? | 70392? | Clean locus | Handstone | disc | fine abraded | S convex | flat | 122 | 120 | 50 | Beachrock | Bifacial tool | ||||||

| AI/32 | 181515 | 9 / | Grinding slab | loaf ? | 339 | 142 | 82 | fragment | Basalt | St not found | ||||||||

| W9909 | 186023 | 09-oct | Grinding slab | loaf | 268 | 99 | 54 | Basalt | Asymmetric T-sec | |||||||||

| 7514 | baulk | Grinding slab | slab ? | Feldspar basalt | St not found | |||||||||||||

| 6 b | Grinding slab | loaf | 330 | 112 | 55 | Beachrock | Simm | |||||||||||

| 182300 | Grinding slab | loaf | fine abraded | flat | flat | 160 | 88 | 32 | basalt | St not found | ||||||||

| 184607 / 2 | Grinding slab | loaf | fine abraded | concave | concave | 236 | 108 | 55 | Feldspar basalt ? | St not found | ||||||||

| 181809 | Grinding slab | loaf/ handstone | 168 | 118 | 69 | fragment | Vesicular basalt | St not found | ||||||||||

| 185801 | 11 a ? | Grinding slab | Non identical | fragment | Basalt | St not found | ||||||||||||

| 181546 | Grinding slab | Non identical | fragment | basalt | St not found | |||||||||||||

| 181999 | Grinding slab | Non identical | hand shine | fragment | Limestone | St not found | ||||||||||||

| En | Gev | Kioto | Excavations | |||||||||||||||

| Locus | Basket | Stratum | Description | Interior measure | Working face section | Exterior measure | Preservation | Rock formation | Notes | |||||||||

| Type | Sub-type | Upper axis 1 | Upper axis 2 | Length | Lower wear | Longwise section | Lateral section | 1 Axis | Axis 2 | Length | Weight | |||||||

| 564 | 5179-1 | KIVa | Handstone | Asymmetrical loaf | fine abraded | flat | very slightly convex | 167 | 132,00 | 51,00 | 1479 | workable fragment | porous basalt | Fine abraded work-face patch only on left front; reuse of fragment. | ||||

| 577 | 5243 | KIVb | Handstone | Small | fine abraded | flat | slightly convex | 96 | 74 | 37 | 641 | workable fragment | porous basalt | Probably a fragment of an oval-shape small handstone (possibly trapezoid). | ||||

| 587 | 5267 | KIVb | Grinding slab | rectangular profile | fine abrader | flat | flat | 204 | 159 | 61 | 2000 | small fragment | basalt | Description based on original drawing. | ||||

| 587 | 5289 | KIVb | Grinding slab | Asymmetrical loaf | fine abraded | flat | 107 | 100 | 45 | workable fragment | porous basalt | Fig. 7:2 | Description based on original drawing. | |||||

| 640 | 6128 | surface | Unfinished tool | Handstone, small, oval | coarse abraded | sightly convex | 157 | 138 | 57 | 1357 | large fragment | porous basalt | Fig. 7.1 | Coarse work-face and unfinished shape hint that the tool was not used. | ||||

| 647 | 6137 | KIII | Handstone | Symmetrical loaf | fine abraded | very slightly convex | 205,00 | 147,00 | 64 | 2000 | workable fragment | basalt | Description based on original drawing. | |||||

| 663 | 6308 | KIV | Handstone | Asymmetrical loaf | 153 | 55 | fine abraded | flat | slightly convex | 153 | 113 | 66 | 1350 | small fragment | porous basalt | Back: fine abraded shined patches (possibly due to palm holding of handstone); front: fine abraded left use-face. | ||

| 663 | 6309 | KIV | Grinding slab | rectangular profile | coarse, fine abraded | flat | flat | 195,00 | 150,00 | 70,00 | small fragment | vesicular basalt | ||||||

| 663 | 6342 | KIV | Handstone | Asymmetrical loaf | fine abraded | very slightly convex | 138 | 114 | 50 | 1148 | small fragment | basalt | Estimated weight of complete; description base on drawing. | |||||

| 676 | 6343 | surface | Quern | Round, shallow | 335 | 328 | 27 | abraded | very slightly concave | 586,00 | 550,00 | 79 | complete | limestone | Unmodified irregular round, squashed pebble; description based on original drawing. | |||

| 703 | 6417-2 | KIV | Grinding slab | Trapeze profile | slightly concave | slightly concave | 151 | 130 | 78 | large fragment | vesicular basalt | Description based on original drawing. | ||||||

| 703 | 6432 | KIV | Grinding slab | Irregular oval, reuse | fine abraded | slightly concave | very slightly concave | 260 | 190 | 100 | fragment | vesicular basalt | Reuse of large slab along lateral axis, perpendicular to original use. | |||||

| 711 | 6337 | KII | Handstone | Asymmetrical loaf | fine abraded | very slightly convex | flat | 252,00 | 135,00 | 83 | fragment | basalt | Fig. 7:3 | Irregular triangular lateral profile. | ||||

| 723 | 6372 | KIV | Grinding slab | Trapezoid loaf | fine abraded | slightly concave | 363,00 | 115,00 | 70 | complete | porous basalt | Fig. 7: 4 | The only complete grinding mill in the assemblage. | |||||

| 744 | 6493 | KII | Grinding slab | Oval, reused | fine abraded | slightly concave | flat | 381 | 328 | 108 | workable fragment | basalt | Fig. 7: 5 | Work-face on back ends 30 ahead left edge; probable reuse. | ||||

| 744 | 6495 | KII | Grinding slab | Symmetrical loaf | fine abraded | slightly concave | very slightly concave | 240 | 143 | 58 | workable fragment | vesicular basalt | Lateral section very slightly concave, not like in drawing. | |||||

| 744 | 6476 | KII | Handstone | Symmetrical loaf | fine abraded | slightly convex | flat | 175 | 124 | 47 | 1514 | workable fragment | basalt | Estimated weight of complete GST 3 kg. | ||||

| 744 | 6498 | KII | Handstone | Symmetrical loaf | fine abraded | slightly convex | flat | 187 | 131 | 64 | 1867 | workable fragment | porous basalt | Estimated weight of complete handstone 3.5 kg, fits grinding on large slab (public device?). | ||||

| 747 | 6490 | KIV | Grinding slab | Trapeze profile | fine abraded | slightly convex | flat | 352 | 343 | 180 | workable fragment | vesicular basalt | Work-face end 90 ahead of back-edge evident by pecked & coarse abraded stripe on front. | |||||

| 166 | 1206 | KI | Grinding slab | Oval | 220 | 200 | fine abraded | flat | 227 | 203 | 53 | complete | basalt | Fig. 7: 6 | ||||

| 171 | 1216 | KII | Grinding slab | slab | 225 | 165 | abraded | flat | 177 | 152 | 87 | 2000 | small fragment | porous basalt | Fig. 7: 7 | |||

| Japanese | Mission | Excavations | ||||||||||||||||

| 401 | 1320 | Groove handstone | square/ trapezoid | smooth | flat | very slightly convex | 193 | 118 | 63 | almost complete | vesicular basalt | Fig. 7:8 | In soil deposit with Hellenistic pottery; Assyrian type B | |||||

| Khirbet | Auja | el-Fuqa | ||||||||||||||||

| Locus | Basket | Stratum | Description | Interior measure | Working face section | Exterior measure | Preservation | Rock formation | Notes | |||||||||

| Type | Sub-type | Upper axis 1 | Upper axis 2 | Length | Lower wear | Longwise section | Lateral section | 1 Axis | Axis 2 | Length | Weight | |||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | loaf | concave | 125 | <130> | 57,00 | Limestone | Asymmetric | ||||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | concave | concave | 60 | 55 | 85 | small fragment | sandstone | ||||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | slab | concave | concave | 180 (280) | -175 | 190 | fragment | Breccia | Fig. 2:1 | Rectangular, rounded | |||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | Loaf | flat | flat | -270 | -123 | -55 | almost complete | Limestone | Fig. 2:2 | Asymmetric | |||||||

| Surface | Handstone | small oval | concave | concave | 60(130) | (100.00 | -30 | fragment | Feldspar basalt | Fig. 2:4 | Lens, asymmetrical/ bifacial | |||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | Loaf | concave | concave | 220(250) | ((153) | -57 | almost complete | Limestone | Convex, symmetrical | ||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | Loaf | concave | concave | 110(200) | (135) | -57 | fragment | Gray basalt | Lens | ||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | oval | concave | flat | 225(300) | -180 | -110 | fragment | Convex, beveled | |||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | oval | 137(230) | -130 | -40 | fragment | Limestone | Convex, arc | ||||||||||

| Surface | Handstone | small oval | concave | concave | 113(140) | -90 | -29 | fragment | Hard sandstone | Lens/ bifacial | ||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | flat | flat | 12,00 | 50,00 | 85,00 | fragment | Hard sandstone | ||||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | slab? | concave | concave | 140 | 110 | -70 | fragment | Vesicular basalt | |||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | oval | concave | convex | 180(280) | -175 | -90 | fragment | Breccia | Rectangular, rounded | ||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | Loaf | concave | flat | -225 | -130 | -460 | fragment | Limestone | Lens rectangular | ||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | slab | concave | flat | 170(370) | 225(300) | <(105) | fragment | Basalt | Fig. 2:1 | Ridge on end | |||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | Loaf | concave | convex | 150 (220) | -133 | -840 | fragment | Limestone | Convex, asymmetrical | ||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | nodule | concave | concave | (270) | (180) | <100> | fragment | Breccia | Irregular rectangle | ||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | oval | concave | flat | 58(300) | -178 | -98 | fragment | Breccia | rectangular, convex | ||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | slab | flat | flat | 200 | 150 | 45 | fragment | Flint breccia | Flat | ||||||||

| Surface | Grinding slab | Loaf | concave | convex | 200(<220) | (<120) | -57 | fragment | Limestone | Convex, symmetrical | ||||||||

| Surface | Handstone | small rectangular | concave | concave | (<-275>) | -156 | -95 | almost complete | Flint breccia | Fig. 2:2 | Convex, rectangular, asymmetrical | |||||||

Notes

- Many are of Cypriot origin and possibly brought to Tel Dor by ship as ballast and unloaded to make space for local cargo (Eitam unpublished c; Gilboa’, Sharon & Zorn 2014).

- It seems that some type of material was placed under the narrow slab to collect the flour. Moreover, although the term “saddle quern” is still common among archaeologists, it is misleading as the concave “saddle” form results from intensive, prolonged use of a slab initially with a flat grinding surface.

- The upper stones with lateral grips with a concave longitudinal section and a convex longitudinal section coupled with convex slabs (Stroulia et al. 2017, 9, fig. 6) common to Greece during the Neolithic and to the Western Mediterranean and Egypt in the Iron Age is unknown in Israel.

- Other researchers have come to the same incorrect interpretation (Milevski 2019, pl. 4.4, pl. 5.2, pl. 3, pl. 17.1; Sass 2000, fig. 12.4: 3 [Early Bronze period], fig. 12.5:4, fig. 12.6:3, fig. 12.8:3; Sass & Cinamon 2006, fig. 18.8:107, 111, 117, fig. 18.10:138, 154; Ben-Ami 2005b, fig. V.6:2 [very likely a drawing error] 4, 5; Ben-Ami 2005a, fig. III.19:10; Bennet & Bienkowski 1995, fig. 9.2:5; Yadin & Geva 1986,fig. 38:12, fig. 39:1, 8, 9).

- Unfortunately, relatively few archaeologists have adopted the criteria of Elliott (1991) and Wright (1992) in defining lower and upper stones (slabs and handstones). Wright (1992) and Hovers (1996) based on the concavity of the lower and convexity of the handstone working faces stem from simple measurements. Yahalom-Mark’s criterion is based on the incorrect assumption that the handstone is 50% narrower than its lower counterpart. This is disproved even among her assemblage where the width of one lower stone is equal to that of an upper one (Yahalom-Mark 2007, 651; Yahalom-Mark & Mazar 2006, 487; see fig. 13.6:3 compared to fig. 13.6:2).