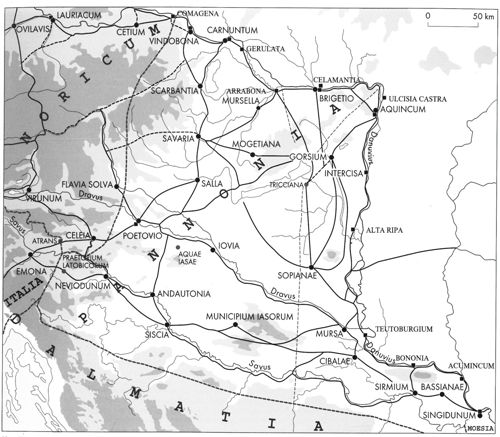

It has become a widely known and used topos in late Antique literature that Pannonia (fig. 1) was lost or destroyed in the year 260 following two usurpations and a devastating Sarmatian and Quadic incursion. Similar case can be observed in Illyricum and Pannonia after the battle of Hadrianople in 378. Naturally, the latter event did not mean the total destruction and loss of the entire prefecture, but its memory vividly survived in contemporary literature, even thirty years after Hadrianople1. In my paper I intend to deal with the events in Pannonia in 260 which was the most turbulent year of the province since the end of the Marcomannic wars2. After Marcus Aurelius’ and Commodus’ northern wars ended in 180, Pannonia fully recovered and under the rule of the Seueri a new prosperous age could have been observed (in the epigraphical and in the archaeological material too). Several new settlements were elevated to the municipal rank or received colonial status and no serious Barbarian incursions can be observed in these decades3.

The crisis began with Ingenuus’ usurpation in 258 or 2604. It must also be added that the Pannonian army weakened significantly in 257 as Valerian used Pannonian vexillations in his campaign against the Persians5. Polemius Silvius specifies Sirmium as the place where Ingenuus was proclaimed emperor6. Only Ingenuus’ biography in the Historia Augusta, replete with fictional elements, offers an explanation for the revolt: quam quod instantibus Sarmatis creatus est imperator, qui fessis rebus mederi sua uirtute potuisset (9.1), suggesting that the Sarmatian threat may have played a role in his elevation by the Illyrian army. The greatest confusion was caused by the Historia Augusta, which specified 258, the consular year of Tuscus and Bassus, as the year of the rebellion7, while according to Aurelius Victor, it took place after Valerian’s defeat by the Persians8. As I see no reason for dating Valerian’s defeat earlier than 260, given that the emperor’s coins struck in 260 and the Egyptian papyri mentioning his name can hardly be left out of consideration9, there is no need and possibility to date Ingenuus’ usurpation before 260. The author of the HA in the uitae of the Soldatenkaiser after 238, esp. in the biography of the Thirty Tyrants, nearly always used fictive biographical elements, letters, orations, consular dates10. In view of this, the consular date 258 concerning the usurpator, even if it was a correct one, cannot be accepted. Ingenuus’ usurpation cannot have lasted for long (esp. not two years) because there are no coins bearing his name (or any overstikes)11. While the Historia Augusta and Aurelius Victor claim that Ingenuus was the legatus of Pannonia12, Zonaras and the Historia Augusta also add that he was proclaimed emperor by the Moesian troops together with the acceptance of the Pannonians13. In view of the latter and the fact that he had his headquarters at Sirmium during the rebellion, it is possible that the two provinces were governed jointly. Ingenuus may have been one of the generals whom Gallienus entrusted with the defence of Illyricum, Italy and Greece, and who thus commanded the local troops, while the emperor dealt with the situation in Germania14. There is no other antique reference to Ingenuus’ appointment. The consequences of the rebellion are recounted in detail in literary sources: Gallienus hastened to Illyricum and the main army led by Aureolus defeated the Illyrican troops in a heated battle at Mursa15. Ingenuus was either murdered by his own bodyguards while fleeing16, or he committed suicide17. According to Ingenuus’ biography in the Historia Augusta (9.3, cf. also 10.1), the emperor exacted a bloody vengeance, while Petrus Patricius (F 180 Banchich = Anon. Cont. F 5.2 Müller) recounts the cruelty of the soldiers towards one another.

The name and story of Regalian, the usurper following on Ingenuus’ heels, has only been preserved in the Latin historiographic tradition18, the biography in the Historia Augusta is largely fictitious (Tyr. Trig., 10) and the few reliable bits of information originate from the lost Kaisergeschichte (perhaps transmitted through breviaries)19. The Historia Augusta has nothing to say about Regalian’s descent, his cursus or his activities. Regarding this fact, his appointment as dux Illyrici can hardly be regarded as a fact20. The Epitome de Caesaribus too specifies Moesia as the place where he was proclaimed (32.3), the HA adds that he was elevated by the Moesian troops: auctoribus imperii Moesis (Tyr. Trig., 10.1). A remark by Aurelius Victor indicates again that not too much time did elapse between the two pronunciamentos, as clearly the same year, 260 indicated by the adverb mox: moxque Regalianum, qui receptis militibus, quos Mursina labes reliquos fecerat, bellum duplicaverat (33.2). Polemius Silvius indicates the place of the proclamation as Sirmium, although he is probably mistaken21. A corrupt name recorded by Eutropius gave rise to the biography of another, wholly fictitious eastern (Isaurian) usurper in the Historia Augusta (Tyr. Trig., 26), the figure of Trebellian: Nam iuvenis in Gallia et Illyrico multa strenue fecit occiso apud Mursam Ingenuo, qui purpuram sumpserat, et Trebelliano (Eutr. 9.8)22.

Regalian’s successful campaigns against the Sarmatians are mentioned only in the HA in Tyr. Trig., 10.2: Hic tamen multa fortiter contra Sarmatas gessit23: unless the legend victoria avgg on the reverse of one of his coin types (Göbl 1970, 27 n° X 4 = MIR 43, n° 1715 = Dembski et al., R 12.1-3.) refers to this). If he really was the governor of Upper Pannonia before his usurpation he could not fight against the Sarmatians as they lived neighbouring Pannonia inferior. This passage in the Historia Augusta would be the single evidence for the arrival and settlement of the Roxolani in the Hungarian Plain. Aside from two passages listing the European Barbarian enemies of the empire (SHA, Marc., 22.1, Aurel. 33.4), this is the only passage in the Historia Augusta where the name of the Roxolani appears, but here it was used a synonym of the world Sarmatae used in the same line. However, the author of the uita locates Regalian’s victory over the Sarmatians and his victories against the Sarmatians not in Pannonia, but to the Scupi area in Moesia24.

Aside from more than forty coin hoards left in their wake, the Quadic-Sarmatian incursions into Pannonia are recorded by the sources drawing from the Kaisergeschichte and by other texts too25, which could have been known to the Historia Augusta’s compilator and thus the passage in question cannot be regarded as textual evidence for the arrival and settlement of the Roxolani in the Alföld (a migration which nonetheless seems likely)26. The circumstances of Regalian’s death as recorded in the uita are unclear, because the ablative absolutes (auctoribus Roxolanis consentientibusque militibus) can have multiple meanings (who killed Regalian? should we suspect the Sarmatians – in which case the passage could be interpreted as textual evidence for the Sarmatian incursion – or his own soldiers?), and a similar course of events – i.e. that his demise was the consequence of a Sarmatian-Roman agreement – seems most unlikely. Similarly to Ingenuus, Regalian was defeated by Gallienus in the sources depending from the EKG27. It is more probable that this tradition was the genuine one.

The data on Regalian in the literary sources need to be integrated with the textual evidence on the Sarmatian-Quadic incursion and the archaeological record. The information provided by the Kaisergeschichte is clear enough: Regalian was proclaimed by the troops that had remained loyal to Ingenuus. However, this cannot have taken place in Moesia because coins minted by the usurpator are only known from Pannonia Superior, the Carnuntum area and NW Pannonia (see below)28, suggesting that Moesia did not come under Regalian’s control. According to Jehne’s chronology for the causes giving rise to the rebellion, it was principally a response to the Alemannic inroad into Italy in the winter of 259–260, which had to be crushed personally by Gallienus29. This would explain why the emperor had departed from Pannonia before dealing with the situation in the province, as well as the absence of his reliable troops. According to the traditional chronology, the rebellion broke out after news had been received of Valerian’s capture30, indicating a date in the latter half of 260. He overstruck the earlier coins in circulation, especially antoniniani, which have preserved the correct form of his cognomen (the single reliable evidence) and the abbreviation of his full name (p(—) c(—) re-galianvs) (RIC V.2, n° 1-8 = MIR 43, n° 1708-1719 = Dembski et al. 2007, R 1-16)31. A recently found fleet diploma from 202 (AE, 2001, 2161 = RMD, 5, 449) and his extremely rare cognomen provide clues for his origins: the name of the consul suffectus, C. Cassius Regallianus, indicates that the usurper’s full name was probably P. Cassius Regalianus32. He also issued coins (RIC V.2, n° 1-2) in the name of Sulpicia Dryantilla, his wife (or, less likely, his mother). The extremely rare coins have only been found in Pannonia superior, principally in the Carnuntum area, and there can be no doubt that they had been minted there33. There is nothing to support Mócsy’s contention that the usurper had retreated to Carnuntum shortly before his downfall34. The findspots of the coins are rather a reflection of Regalian’s original rank: he had perhaps been the governor of Pannonia superior. Fitz interpreted the abbreviation avgg appearing on the coins as standing for Regalian and Postumus, the two Augusti35, but it seems more likely that it referred to the usurper and his wife36.

Based on the testimony of the Apetlon hoard, whose latest coin was an issue of Dryantilla37, Regalian assumed power at the time of the most devastating attack against Pannonia. The Sarmatian incursion is recounted in late antique Latin sources, almost all of them drawing from the Kaisergeschichte38, and it is also mentioned in a panegyricus addressed to Constantius Chlorus at Trier in 297-29839, reflecting the impact of the Barbarian attack40. Only the breuiaria mention the participation of the Quadi but findspots of coin hoards in NW Pannonia confirm the written source. Another common element of these sources, with the exception of Hieronymus’ Chronicon, is that the Pannonian incursion was enumerated among the events of the general crisis (the Alamann incursion into Italy, raid in Hispania, the loss of Raetia and Dacia, the raids of the Goths in Greece and Asia minor, the Persian campaign) of the empire around 26041. Unfortunately, with the exception of the panegyric, they did not follow the chronological or geographical order (for instance, the loss of Dacia in 262 precedes the Pannonian events42).

| Pan. Lat. 4(8).10.2 | Persians |

Raetia Noricum |

Pannonia | Italy | _ | _ | _ |

| Eutr. 9.8 | Gallia | Italy | Dacia | Goths | Pannonia | Hispania | Persians |

| Oros. 7.22.7 | Raetia | Italy | Goths | Dacia | Pannonia | Hispania | Persians |

| Jord., Rom., 287 | Persians | Gallia | Italy | Goths | Pannonia | Hispania | _ |

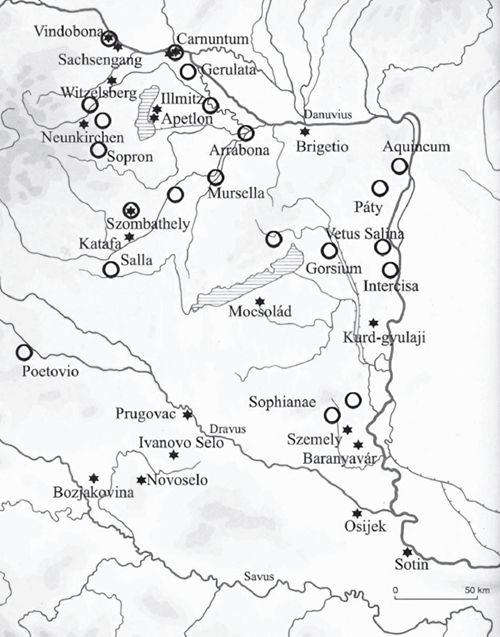

In addition to the Apetlon hoard, a series of some forty other coin hoards buried between 258 and 260 attest to the devastation (see Appendix)43. The incursion affected not only Pannonia, but all the Danubian provinces, described as undergoing a general crisis in the literary sources – buried coin hoards have been found in all of these provinces.44 Some of these hoards esp. in Southern Pannonia may have been deposited during the rebellion of Ingenuus and Regalianus, but their majority can be clearly linked to the Barbarian raids. The latest coins in the hoards were minted in 258–259, indicating the terminus post quem, as well as marking the last period when coins issued by the lawful emperor reached Pannonia before the outbreak of the rebellion.45 While the direct causes of the incursion remain unknown, its participants were quite clearly the Quadi and the Sarmatians. The compilator of the Historia Augusta had few reliable sources at his disposal aside from the Kaisergeschichte and/or the breviaries. It seems likely that he had added the Roxolani owing to the prominent role of the Sarmatians and the mention of Moesia in his sources46. The relevant passage in the Epitome de Caesaribus could only be cited as proof for the arrival and settlement of the Roxolani if the original source had specifically referred to the Roxolani of the Hungarian Plain; however, the biographer of the Historia Augusta located this tribe in their earlier settlement territory and described the events as taking place in the Scupi area in Moesia. The likelihood that the Roxolani were meant is very slim47. The information contained in the literary sources does not support other theories such as the connection between Gallienus and the Sarmatians-Roxolani attacking Pannonia, or the resettlement of the latter48 (although neither do the sources disallow these contentions). What is obvious is that the author of the biographies preserved in the Historia Augusta was aware of the Sarmatian threat during Ingenuus’49 and Regalian’s time, and Regalian is even credited with some success in the campaigns against them50.

Based on the testimony of the literary sources and the archaeological record, principally the even distribution of coin hoards in Pannonia51, the attack was directed against Pannonia and not against Italy52. Major devastations can be observed esp. in the limes forts and their broader area in Pannonia inferior. The Sarmatian attacks are reflected by coin hoards and destruction levels in Aquincum, Gorsium, Intercisa (both in the castellum and the vicus) and Matrica53. It is also likely that the auxiliary castellum or vicus at Albertfalva was abandoned at this time,54 as was the governor’s palace in Aquincum55, while defence works were raised to protect the Aquincum canabae56. The temple area at Tác was destroyed in 260; an inner fort for military purposes would later be built in the same place, in the mid-4th century57. A part of the civilian town in Brigetio was abandoned in consequence of the incursions and with time, the entire civilian population moved into the military town and, later, into the military fort58. The headquarters building of Matrica was destroyed, the cellar of the aerarium under the shrine was filled up with the burnt debris of the collapsed roof (a coin of Salonina Augusta minted between 253 and 258 was found in the fill)59. The devastation took its toll in terms of human life as well as in the destruction of buildings and material goods (e.g. the disappearance of the imported wares, such as the Samian ware from Pfaffenhofen60), and it is also reflected in the most serious change in the province’s epigraphic habit. In some areas, restoration works sometimes lasted for several decades and it is possible that some of the construction work during the Tetrarchy can be linked to the earlier devastations61. Some 6000 inscribed stone relics are known from Pannonia, which had become a totally Latin-speaking province latest under the Severi. The number of inscriptions erected between 260 and the end of the Roman rule (including all Early Christian funerary inscriptions) is barely 250, accounting for 4 percent of the epigraphic material62. The Roman import wares (such as terra sigillata chiara amphores etc.) in Pannonia after 260 never reached the same level as in the first half of the 3rd century63.

Turning back to the question of this paper, one of the greatest crises of Pannonia was in 260 AD. The starting point was the military crisis, the Barbarian threat that caused Ingenuus’ and Regalianus’ usurpations. The emperor himself had to deal with them in both cases. The usurpations caused serious casualties in the army (battle of Mursa) and in the civilian population. As the Roman troops garrisoned in the province weakened, came a devastating incursion of the Sarmatians and the Quadi. Pannonia did not lose, but the consequences of this year was brutal: burnt and abandoned settlements, military forts, a loss of population and economic crisis. The latter can be pointed in the archaeological (e.g. disappearance of imported wares) and epigraphic material (the shockingly low ratio of inscriptions after 260). What can be called general crisis, if not this?

References

- Alföldi, A. (1942): “Aquincum a későrómai világban”, Budapest története, 1, 670-746.

- Alföldi, A. (1967): Studien zur Geschichte der Weltkrise des 3. Jahrhunderts nach Christus, Darmstadt 1967.

- Alföldi, M.R. (1959): “Zu den Militäreformen des Kaisers Gallienus”, in: Limes-Studien, Vorträge des 3. Internationalen Limes-Kongresses in Rheinfelden/Basel 1957, Basel, 13-18.

- Barkóczi, L. (1951): Brigetio, Dissertationes Pannonicae 2.22, Budapest.

- Barkóczi, L. (1957): “Die Grundzüge der Geschichte von Intercisa”, in: Intercisa (Dunapentele), II, Geschichte der Stadt in der Römerzeit, Budapest, 527-531

- Barkóczi, L. (1959): “Transplantation of Sarmatians and Roxolans in the Danube Basin”, AAntHung, 7, 443-453.

- Barnes, T.D. (1972): “Some persons in the Historia Augusta”, Phoenix, 26, 140-182.

- Bíróné Sey, K. (1963): “A kistormási éremlelet – Le trésor de monnaies romaines de Kistormás”, Folia Archaeologica, 15, 55-68.

- Bíróné Sey, K. (1985): Pannoniai pénzverés. Budapest.

- Bíróné Sey, K. and Palágyi, S. (1983): “A balácai éremlelet”, Communicationes Archaeologicae Hungariae, 1983, 63-78.

- Bleckmann, B. (1992): Die Reichskrise des III. Jahrhunderts in der spätantiken und byzantinischen Geschichtsschreibung. Untersuchungen zu den nachdionischen Quellen der Chronik des Johannes Zonaras, Quellen und Forschungen zur antiken Welt 11, Munich.

- Borhy, L. (2004): “Brigetio. Ergebnisse der 1992–1998 durchgeführten Ausgrabungen (Munizipium, Legionslager, Canabae, Gräber-felder)”, in: Šašel Kos, M. and Scherrer, P., ed.: The Autonomous Towns of Noricum and Pannonia, Pannonia 2, Situla 42, Ljubljana, 231–251.

- Borhy, L. (2005): “Militaria aus der Zivilstadt von Brigetio (FO: Komárom/Szőny–Vásártér). Indirekte und direkte militärische Hinweise auf Beginn, Dauer und Ende der Zivilsiedlung im Lichte der neuesten archäologischen Forschung”, in: Borhy, L. and Zsidi, P., ed.: Die norisch-pannonischen Städte und das römische Heer im Lichte der neuesten archäologischen Forschungen. II. Internationale Konferenz über norisch-pannonische Städte, Budapest, 2002. szeptember 11-14, Aquincum Nostrum II.3, Budapest 2005, 75-81.

- Bray, J. (1997): Gallienus. A Study in Reformist and Sexual Politics, Kent Town.

- Brecht, S. (1999): Die römische Reichskrise von ihrem Ausbruch bis zu ihrem Höhepunkt in der Darstellung byzantinischer Autoren, Althistorische Studien der Universität Würzburg 1, Rahden.

- Christol, M. (1975): “Les règnes de Valérien et de Gallien (253-268) : travaux d’ensemble, questions chronologiques”, ANRW, II.2, 803-827.

- De Blois, L. (1976): The Policy of the Emperor Gallienus, Leiden.

- Dembski, G., Winter, H. and Woytek, B. (2007): “Regalianus und Dryantilla. Historischer Hintergrund, numismatische Evidenz, Forschungsgeschichte. MIR 43 – Neubearbeitung”, in: Alram, M. and Schmidt-Dick, F., ed.: Numismata Carnuntina. Forschungen und Material, Vienna 2007, 523-596.

- Drinkwater, J. F. (1987): The Gallic Empire. Separatism and Continuity in the North-Western Provinces of the Roman Empire A.D. 260-274, Historia Einzelschriften 52, Stuttgart.

- Eck, W. (2002): “Prosopographische Bemerkungen zum Militärdiplom vom 20.12.202 n. Chr. Der Flottenpräfekt Aemilius Sullectinus und das Gentilnomen des Usurpators Regalianus”, ZPE, 139, 208-210.

- Fitz, J. (1966): Ingenuus et Régalien, Collection Latomus 81, Brussels.

- Fitz, J. (1976): La Pannonie sous Gallien, Collection Latomus 148, Brussels.

- Fitz, J. (1978): Der Geldumlauf der römischen Provinzen im Donaugebiet Mitte des 3. Jahrhunderts, Budapest-Bonn.

- Fitz, J. (1993-1995): Die Verwaltung Pannoniens in der Römerzeit, I-IV, Budapest.

- Fitz, J. (2001): Silbermünzen im Sand. Der Schatzfund von Nagyvenyim, Dunaújváros.

- Forschungen (2003): Forschungen in Aquincum 1969–2002 zu Ehren von Klára Póczy, Aquincum nostrum II.2, Budapest.

- Gabler, D. (1978): “Die Sigillaten von Pfaffenhofen”, AArchHung, 30, 77-147.

- Gabler, D. (1982): “Nordafrikanische Sigillaten in Pannonien”, Savaria, 16, 313–333.

- Gabler, D. (1988): “Spätantike Sigillaten in Pannonien. Ein Nachtrag zu den nordafrikanischen Sigillaten”, Carnuntum Jahrbuch, 9-40.

- Geiger, M. (2013): Gallienus, Frankfurt.

- Gerhardt, T. and Hartmann, U. (2008): “Fasti”, in: Johne, ed. 2008, 1055-1198.

- Gerov, B. (1977): “Die Einfälle der Nordvölker in den Ostbalkanraum im Lichte der Münzschatzfunde I. Das II. und III. Jahrhundert (101-284)”, ANRW, II.6, 110-181 = Gerov, B.: Beiträge zur Geschichte der römischen Provinzen Moesien und Thrakien. Gesammelte Aufsätze, Amsterdam 1980, 361-432.

- Glas, T. (2014): Valerian. Kaisertum und Reformansätze in der Krisenphase des Römischen Reiches, Paderborn.

- Goltz, A. and Hartmann, U. (2008): “Valerianus und Gallienus”, in: Johne, ed. 2008, 223-295.

- Göbl, R. (1954): Der römische Münzschatzfund von Apetlon, Wissenschaftliche Arbeiten aus dem Burgenland 5, Eisenstadt.

- Göbl, R. (1970): Regalianus und Dryantilla. Dokumentation. Münzen, Texte, Epigraphisches, Denkschriften der Österr. Akademie der Wissenschaften, phil.-hist. Klasse 101, Vienna-Cologne-Graz.

- Halfmann, H. (1986): Itinera principum. Geschichte und Typologie der Kaiserreisen im römischen Reich, HABES 2, Stuttgart.

- Harmatta, J. (1970): Studies in the History and Language of the Sarmatians, Szeged.

- Hárshegyi, P. and Ottományi, K. (2013): “Imported and local pottery in late Roman Pannonia”, in: Lavan, L., ed.: Local Economies? Production and Exchange of Inland Regions in Late Antiquity, Leiden, 471–528.

- Istvánovits, E. and Kulcsár, V. (2017): Sarmatians. History and Archaeology of a Forgotten People, Mainz.

- Jehne, M. (1996): “Überlegungen zur Chronologie der Jahre 259 bis 261 n. Chr. im Lichte der neuen Postumus-Inschrift”, BVBl, 61, 185–206.

- Johne, K.-P., ed. (2008): Die Zeit der Soldatenkaiser. Krise und Transformation des Römischen Reiches im 3. Jahrhundert n.Chr. (235-284), I-II, Berlin 2008.

- Kérdő, K. (2003): “Der Statthalterpalast von Aquincum”. in: Forschungen 2003, 112-119.

- Kienast, D. [1990] (1996): Römische Kaisertabelle. Grundzüge einer römischer Kaiserchronologie, Darmstadt.

- Kienast, D., Eck, W. and Heil, D. [1990] (2017): Römische Kaisertabelle. Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie, Darmstadt.

- Kovács, P. (2000): “A grave from the Hun period at Százhalombatta”. in: Matrica – Excavations in the Roman fort at Százhalombatta (1993–1997), Studia Classica – Series Historica 3, Budapest, 121-171 = “Hun kori sír Százhalombattán”, Communicationes archaeologicae Hungariae 2004, 123–150.

- Kovács, P. (2004); “The late Roman epigraphy in Pannonia (260-582)”, in: Németh, G. and Piso, I., ed.: Epigraphica II. Papers of the 4th Hungarian Epigraphic Roundtable,1st Rumanian-Hungarian Epigraphic Roundtable, Sarmizegetusa, October 24-26, 2003, Hungarian Polis Studies 11, Debrecen, 185-195.

- Kovács, P. (2014): A History of Pannonia during the Principate, Antiquitas. Reihe 1: Abhandlungen zur alten Geschichte 64, Bonn.

- Kovács, P. (2016): “Notes on the Pannonian foederati”, in: Wolff, C. and Faure, P., ed.: Les auxiliaires de l’armée romaine: des alliés aux fédérés, Actes du sixième Congrès de Lyon, 23- 25 octobre 2014, Paris, 575-601.

- Kovács, P. (2019): Pannonia története a későrómai korban (Kr. u. 284-395), Budapest.

- Kovács, P. and Németh, M.: “Eine neue Bauinschrift aus Aquincum”, ZPE, 169, 249-254.

- Loreto, L. (1994): “La prima penetrazione alamanna in Italia (260 d.C.) come ipotesi alternativa di spiegazione per la storia dei conflitti romano-germanici”, in: Scardigli, B. and P., ed.: Germani in Italia, Rome, 209-237.

- Madarassy, O. (1999): Canabae legionis II Adiutricis, in: Gudea, N., ed: Roman Frontier Studies, Proceedings of the XVIIth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies 1997, Zalaŭ, 643–649.

- Mócsy, A. (1962): “Pannonia”, RE, suppl. IX, 515-776.

- Mócsy, A. (1974): Pannonia and Upper Moesia, London-Boston.

- Mócsy, A. and Fitz, J., ed. (1990): Pannonia régészeti kézikönyve, Budapest.

- Nagy, T. (1962): “Buda régészeti emlékei”, in: Budapest műemlékei II, Budapest, 13-116.

- Nagy, T. (1976): “Albertfalva”, in: Der römische Limes in Ungarn, Székesfehérvár, 90-91.

- Németh, M. (2003): “Militäranlagen von Óbuda”, in: Forschungen 2003, 85–91.

- Nixon, C. E. V. and Saylor Rodgers, B. (1994): In Praise of Later Roman Emperors. the Panegyrici Latini. Introduction, translation, and historical commentary with Latin text of R. A. B. Mynors, Berkeley-Los Angeles-Oxford.

- Numismata Carnuntina (2007): Numismata Carnuntina, III.2, Die antiken Fundmünzen im Museum Carnuntinum. Forschungen und Material, Vienna.

- Peachin, M. (1990): Roman Imperial Titulature and Chronology A.D. 235-284, Studia Amstelodamensia 29, Amsterdam.

- Pflaum, H.-G. (1966): review of J. Fitz, Ingenuus et Régalien, (Collection Latomus 81), REL 44, 538-542.

- Piso, I. (2018): “Das verhängnisvolle Jahr 262 und die amissio Daciae”, in: Vagalinski, L., Raycheva, M., Boteva, D. and Sharankov, N., ed: Proceedings of the First International Roman and Late Antique Thrace Conference. « Cities, Territories and Identities », Plovdiv, 3rd-7th October 2016, Sofia, 427-440.

- Póczy, K. (1977): “Beiträge zur Baugeschichte des Legionslager Aquincum”, in: Studien zu den Militärgrenzen Roms II, Vorträge des 10. Internationalen Limeskongresses in der Germania Inferior, Bonn-Cologne, 373–378.

- Póczy, K. (1990): “Zur Baugeschichte des Legionslagers von Aquincum zwischen 260–320”. in: Akten des 14. Internationalen Limeskongresses 1986 in Carnuntum, Der römische Limes in Österreich 36, Vienna, 689-701.

- Prohászka, P. (2013): “Zu zwei schicksalhaften Ereignissen aus der Geschichte Pannoniens anhand von Münzhorten, Zerstörungshorizonten und schriftlicher Überlieferung”, in: Heinrich-Tamáska, O., ed.: Rauben – Plündern – Morden – Nachweis von Zerstörung und kriegerischer Gewalt im archäologischen Befund, Hamburg, 19-28.

- Ruske, A. (2007): “Die Carnuntiner Schatzfunde III”, in: Numismata Carnuntina 2007, 443-453.

- Saria, B. (1937): “Zur Geschichte des Kaisers Regalianus”, Klio, 30, 352-354.

- Scardigli, B. (1999): “Gallieno e Ingenuo (Anon. post Dionem frag. 5,1–2)”, InvLuc, 21, 389-398.

- Schmid, W. (1964): “Eutropspuren in der Historia Augusta”, in: Bonner Historia-Augusta-Colloquium 1963, Bonn, 123-133.

- Stein, A. (1914): “Regalianus”, RE, IA.1, 462-464.

- Stein, A. (1916): “Ingenuus 2)”, RE, IX.2, 1552-1553.

- Stein, A. (1940): Die Legaten von Moesien, Dissertationes Pannonicae 1.11, Budapest.

- Swoboda, E. [1949] (1964): Carnuntum. Seine Geschichte und seine Denkmäler, Graz-Cologne.

- Syme, R. (1971): Emperors and Biography. Studies in the Historia Augusta, Oxford.

- Szirmai, K. (2003): “Auxiliarkastell und vicus in Albertfalva” in: Forschungen 2003, 93–95.

- Tóth, E. (1989): “Templum provinciae in Tác?”, Specimina Nova, 5, 43–58.

- Tóth, E. (1991): “Templum provinciae Tácon? (Megjegyzések a táci római település értelmezéséhez)”, A Tapolcai Városi Múzeum Közleményei, 2, 97–111.

- Visy, Z. (1977): Intercisa, Budapest.

- Visy, Z. (1985): “A dunaújvárosi római utazókocsi rekonstrukciója – Die Rekonstruktion des römischen Reisewagens von Dunaújváros”, AErt, 112, 169-179.

- Vulić, H. and Farac, K. (2014): Ostava antoninijana iz Vinkovaca – A hoard of antoniniani from Vinkovci, Acta Musei Cibalensis n.s. 6, Vinkovci.

The relevant sources

The following sources remained concerning Pannonia (given in chronological order):

SHA, Tyr. Trig., 9.1: neque in quoquam melius consultum rei p. a militibus uidebatur quam quod instantibus Sarmatis creatus est imperator, qui fessis rebus mederi sua uirtute potuisset.

10.2: Hic tamen multa fortiter contra Sarmatas gessit, sed auctoribus Roxolanis consentientibusque militibus et timore prouincialium, ne iterum Gallienus grauiora faceret, interemptus est.

10.9: Extat epistola diui Claudii tunc priuati, qua Regiliano, Illyrici duci, gratias agit ob redditum Illyricum, cum omnia Gallieni segnitia deperirent.

10.11: Pertulerunt ad me Bonitus et Celsus, stipatores principis nostri, qualis apud Scupos in pugnando fueris, quot uno die proelia et qua celeritate confeceris. Dignus eras triumpho, si antiqua tempora exstarent.

10.12: arcus Sarmaticos et duo saga ad me uelim mittas, sed fiblatoria, cum ipse misi de nostris.

Pan. Lat., 4(8).10.2: Tunc se nimirum et Parthus extulerat et Palmyrenus aequauerat; tota Aegyptus, Syriae defecerant; amissa Raetia, Noricum Pannoniaeque vastatae; Italia ipsa gentium domina plurimarum urbium suarum excidia maerebat […].

Eutr. 9.8: Alamanni uastatis Galliis in Italiam penetrauerunt. Dacia, quae a Traiano ultra Danubium fuerat adiecta, tum amissa, Graecia, Macedonia, Pontus, Asia uastata est per Gothos, Pannonia a Sarmatis Quadisque populata est, Germani usque ad Hispanias penetrauerunt et ciuitatem nobilem Tarraconem expugnauerunt, Parthi Mesopotamia occupata Syriam sibi coeperant uindicare.

Jer., Chron., p. 220, l Helm: Quadi et Sarmatae Pannonias occupauerunt.

Oros. 7.22.7: Germani Alpibus Raetia totaque Italia penetrata Rauennam usque perueniunt; Alamanni Gallias peruagantes etiam in Italiam transeunt; Graecia Macedonia Pontus Asia Gothorum inundatione deletur; nam Dacia trans Danuuium in perpetuum aufertur; Quadi et Sarmatae Pannonias depopulantur; Germani ulteriores abrasa potiuntur Hispania; Parthi Mesopotamiam auferunt Syriamque conradunt.

Prosp., Chron. Min. I, p. 441, 878: Quadi et Sarmatae Pannonias occupauerunt.

Jord., Rom., 287: Sed dum nimis in regno lasciuiret nec uirile aliquid ageret, Parthi Syriam Ciliciamque uastauerunt, Germani et Alani Gallias depraedantes Rauennam usque uenerunt, Greciam Gothi uastauerunt, Quadi et Sarmatae Pannonias inuaserunt, Germani rursus Spanias occupauerunt.

Appendix

Pannonian coin hoards from 259-260 (after Fitz 1978, 168–201 and Vulić & Farac 2014, with modifications) (fig. 2).

| Findspot | Date (latest coin) | Emperor, Literature |

| Pannonia superior | ||

| Apetlon | 260 | Dryantilla |

| Baláca | 257–259 | Biróné Sey & Palágyi 1983 |

| Balatonboglár | 250s | |

| Balozsameggyes | 259 | |

| Berndorf | 259 | |

| Bonsa | 259 | |

| Carnuntum, fort | 257–258 | FMRÖ III.1, n° 203–204; Ruske 2007 |

| Dvorska | ||

| Garčin I | 260 | |

| Garčin II | 258 | |

| Görgeteg | 259 | |

| Kabhegy | 259 | |

| Korong | 259 | |

| Kurilovec | 259 | |

| Mérges | 258–260 | Saloninus |

| Nagyvázsony | 260 | Regalianus |

| Podvornica | 259 | |

| Rábakovácsi | 256 | |

| Tapolca–Szentgyörgyhegy | 259 | |

| Tüskeszer | 259 | |

| Visnye | Gallienus | |

| Pannonia inferior | ||

| Annamatia | Valerianus, Gallienus | |

| Aquincum | ||

| Biatorbágy I | 260 | Régészeti Kutatások Magyarországon, 2008, 152 |

| Biatorbágy II | Régészeti Kutatások Magyarországon, 2008, 152 | |

| Budaörs | mid-3rd century | |

| Cibalae | 259 | Vulić & Farac 2014 |

| Enying | 259 | |

| Felsőtengelic | 259 | |

| Gorsium | 258 | Fitz 1978, 685–800 |

| Intercisa | 259 | |

| Kistormás | 258 | |

| Környe | 260 | Diva Mariniana |

| Maradék/Maradik | ||

| Mursa | 258? | |

| Nagyberki | 259 | |

| Nagyvenyim | 258 | Fitz 2001 |

| Satnica | ||

| Slavonski Brod | ||

| Szakcs | 259 | |

| Szalacska I | 259 | |

| Szalacska I | 259 | |

| Szalacska V | 259 |

Notes

- Kovács 2016; Kovács 2019, 241-243.

- Mócsy 1962, 566; Mócsy 1974, 206-208, 263-265; Mócsy & Fitz 1990, 45; Kovács 2014, 245-250.

- Mócsy 1962, 563-565; Mócsy 1974, 213-263; Kovács 2014, 175-240.

- PIR2 I 23; PLRE I 457; Stein 1916, 1552-1553; Stein 1940, 105; Alföldi A. 1942, 692; Mócsy 1962, 568, Nagy 1962, 103 n. 335; Fitz 1966, 1-42; Pflaum 1966; Alföldi A. 1967, 101-103, 225-227, 363-364; Barnes 1972, 160-161; Mócsy 1974, 206; Christol 1975, 815-817; Halfmann 1986, 237; Drinkwater 1987, 100-104; Peachin 1990, 40; Bleckmann 1992, 226-241; Fitz 1993, 1001-1003, n° 659; Kienast 1996, 223; Bray 1997, 67-68, 72-78; Jehne 1996, 192-196; Brecht 1999, 264-267, 284-286 n. 5-10; Scardigli 1999, 389-398; Göbl 2000, 60; Goltz & Hartmann 2008, 242, 262-263 n. 203; Gerhardt & Hartmann 2008, 1162-1163; Geiger 2013, 103-105; Glas 2014, 334-336; Kienast et al. 2017, 214.

- Cf. Res gestae divi Saporis l. 20, that explicitly mentions Pannonians.

- Pol. Silv., Chron. min., 1 p. 521, 45: Sub quo Ingenuus Sirmii et Regalianus ibidem […] tyranni fuerunt.

- SHA, Tyr. Trig., 9.1: Tusco et Basso conss. […] Ingenuus, qui Pannonias tunc regebat, a Moesiacis legionibus imperator est dictus.

- Aur. Vict., Caes., 33.2: Ingebum, quem curantem Pannonios comperta Ualeriani clade imperandi cupido incesserat.

- . Peachin 1990, 37-38; Kienast 1996, 214; Glas 2014, 167-180.

- Cf. the mention of one of the same consuls, Tuscus as consul ordinarius in a fictive story in Aurelian’s biography (SHA, Aurel., 13.1); Bleckmann 1992, 226 n. 26, Jehne 1996, 192 n. 11.

- Glas 2014, 335.

- SHA, Tyr. Trig., 9.1: qui Pannonias tunc regebat, Aur. Vict., Caes., 33.1: curantem Pannonios.

- SHA, Tyr. Trig., 9.1: a Moesiacis legionibus imperator est dictus, ceteris Pannoniarum uolentibus; Zon. 12.24: τῶν δὲ ἐν τῇ Μυσίᾳ στρατιωτῶν στασιασάντων; Bleckmann 1992, 238-239.

- Zos. 1.30.2: Ὁρῶν δὲ ὁ Γαλλιηνὸς τῶν ἄλλων ἐθνῶν ὄντα τὰ Γερμανικὰ χαλεπώτερα σφοδρότερόν τε τοῖς περὶ τὸν Ῥῆνον οἰκοῦσιν Κελτικοῖς ἔθνεσιν ἐνοχλοῦντα, τοῖς μὲν τῇδε πολεμίοις αὐτὸς ἀντετάττετο, τοῖς δὲ τὰ περὶ τὴν Ἰταλίαν καὶ τὰ ἐν Ἰλλυριοῖς καὶ τὴν Ἑλλάδα προθυμουμένοις λῄσασθαι τοὺς στρατηγοὺς ἅμα τοῖς ἐκεῖσε στρατεύμασιν ἔταξε διαπολεμεῖν.

- Aur. Vict., Caes., 33.1-2; Eutr. 9.8; SHA, Tyr. Trig., 9.1; Oros. 7.22.10; Pol. Silv., Chron. min., 1 p. 541, 45; Petr. Patr. F 179-180 Banchich = Anon. Cont. F 5.1-2 Müller; wrongly Sirmium, according to the Byzantine tradition: Zonar. 12.24.

- Zonar. 12.24.

- SHA, Tyr. Trig., 9.4.

- Aur. Vict., Caes., 33.2; Eutr. 9.8; Epit. de Caes., 32.3; SHA, Gall., 9.1, Tyr. Trig., 10.9, 12; Pol. Silv., Chron. min., 1 p. 541 ,45.

- PIR C 2; PIR2 R 36, PLRE I 762, Stein 1914, 462-464; Saria 1937; Stein 1940, 105-106; Mócsy 1962, 568-569; Nagy 1962, 54-55; Fitz 1966, 43-63; Pflaum 1966; Alföldi A. 1967, 101-103, 225-226, 364; Göbl 1970; Mócsy 1974, 206-208; Christol 1975, 820; Dembski 1977; Drinkwater 1987, 100-104; Peachin 1990, 40; Bleckmann 1992, 237 n. 71, 239; Fitz 1993, 1003-1005, n° 660; Kienast 1996, 223-224; Bray 1997, 68, 81-84; Jehne 1996, 196-198; Brecht 1999, 284 n. 5; Göbl 2000, 60-61, Anhang I; Eck 2002; Dembski et al. 2007, Goltz & Hartmann 2008, 264-265; Gerhardt & Hartmann 2008, 1163; Geiger 2013, 105-107; Glas 2014, 336-339; Kienast et al. 2017, 215.

- SHA, Tyr. Trig., 10.1: in Illyrico ducatum gerens, 10.9: Illyrici dux.

- Pol. Silv., Chron. min., 1 p. 541, 45: Sub quo Ingenuus Sirmii et Regalianus ibidem […] tyranni fuerunt; Bleckmann 1992, 238 n. 75.

- Schmid 1964, 1964, 126-130; Boer 1972, 171-172; Schlumberger 1974, 148-149.

- Cf. SHA, Tyr. Trig., 10.9, 11.

- SHA, Tyr. Trig., 10.11: Pertulerunt ad me Bonitus et Celsus, stipatores principis nostri, qualis apud Scupos in pugnando fueris, quot uno die proelia et qua celeritate confeceris.

- Pan. Lat., 4(8).10.2; Eutr. 9.8; Jer., Chron., p. 220, l Helm; Oros. 2.22.7; Prosp., Chron. min., I p. 441, 878; Jord., Rom., 287.

- Barkóczi 1957, 527-531; Barkóczi 1959; Fitz 1966, 49; Harmatta 1970, 52-54; Mócsy & Fitz 1990, 45; Istvánovits-Kulcsár 2017, 293-294.

- Aur. Vict., Caes., 33.2: Ingebum […] deuicit moxque Regalianum, qui receptis militibus, quos Mursina labes reliquos fecerat, bellum duplicauerat; Eutr. 9.8: Nam iuuenis in Gallia et Illyrico multa strenue fecit occiso apud Mursam Ingenuo, qui purpuram sumpserat, et Trebelliano; Jehne 1996, 197 n. 77.

- Swoboda 1964, 65.

- Loreto 1994; Jehne 1996

- Cf. Aur. Vict., Caes., 33.2.

- Göbl 1970; Dembski 1977, Göbl 2000, 60-61, Anhang I; Dembski et al. 2007.

- Eck 2002.

- Fitz 1966, 46; Mócsy 1974, 207, fig. 36.

- Mócsy 1974, 206.

- Fitz 1966, 47-48.

- Göbl 1970, 51; Göbl 2000, 60-61, Anhang I.

- Göbl 1954.

- Eutr. 9.8 : Pannonia a Sarmatis Quadisque populata est; Jer., Chron., p. 220, l Helm: Quadi et Sarmatae Pannonias occupauerunt; Oros. 7.22.7; Prosp., Chron. min., I p. 441, 878, Jord., Rom., 287.

- Pan. Lat., 4 (8), 10.2 Pannoniaeque uastatae; Nixon-Saylor Rodgers 1994, 123 n. 33.

- Barkóczi 1959, 146; Mócsy 1962, 566; Nagy 1962, 54-55; Fitz 1966, 49-63; Harmatta 1970, 52-54; Mócsy 1974, 205-206, 208-209; Mócsy & Fitz 1990, 45; Bray 1997, 78, 81, 262-263; Istvánovits & Kulcsár 2017, 294-295.

- It is noteworthy to observe that Aurelius Victor’s and the Epitome de Caesaribus’ longer accounts on Valerian’s and Gallienus’ rule omit this enumeration (32-33).

- Piso 2018, 427-440.

- Fitz 1978, 166-201; Ruske 2007.

- Fitz 1978, 159-225; Gerov 1980, 392-393; Vulić & Farac 2014.

- Nagy 1962, 54; Göbl 1970, 42-43.

- See Epit. de Caes. 32.3.

- Syme 1971, 215.

- Nagy 1962, 55 n. 341; Alföldi M.R. 1959, 15.

- SHA, Tyr. Trig., 9.1.

- SHA, Tyr. Trig., 10.2, 11-12, although in the Scupi area; see above.

- Cf. Bíróné Sey 1985, fig. 40 4, Prohászka 2013.

- Alföldi M.R. 1959, 17; Fitz 1966, 61-63.

- Nagy 1962, 54-55; Visy 1966, 32; Póczy 1977, 373-379; Fitz 1978, 186-187, 191-192, 195, 685-800; Visy 1985, 169-179; Póczy 1990, 689-702; Németh 2003, 88-89; Fitz 2001; Mócsy & Fitz 1990, 45.

- Nagy 1976, 91; Szirmai 2003, 93-95, but see also Kovács 1999, 30.

- Kérdő 2003, 112, 116.

- Madarassy 1999, 643-649.

- Tóth 1989, 43-58; Tóth 1991, 97-111.

- Barkóczi 1951, 9-10; Kovács 1999, 169; Borhy 2004, 241, 249; Borhy 2005, 79-81 (with an earlier dating based on the coin finds).

- Kovács 2000, 91, 93, n° 8.

- Gabler 1978, 77-147; Mócsy & Fitz 1990, 203.

- Kovács & Németh 2009. Cf. Tituli Aquincenses I, 13.

- Kovács 2004.

- Gabler 1982, 313-333; Gabler 1988, 9-40; Hárshegyi & Ottományi 2013, 471-528.