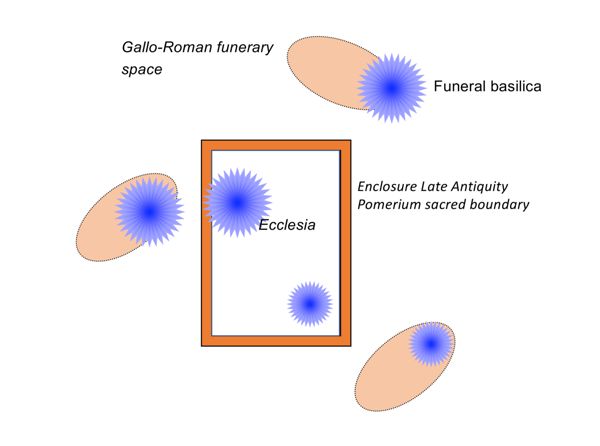

The organization of burial spaces evolved considerably throughout the Middle Ages. The progressive Christianization of towns and the countryside considerably modified the relationship between the dead and the living. In the cities of Antiquity, the necropolises were all located outside the pomerium (often materialized by an enclosure) because of the prohibition of the Law of the XII Tables. This law lasted for a very long time and, even if a few burials were installed within the city walls, no urban cemetery really existed before the 11th century. On the other hand, the organization of the suburbia was transformed: basilicas were built on the tombs of holy people who had been buried in the ancient necropolises. These first churches gave rise to the grouping of burials ad sanctos, often in continuity with the ancient necropolises, as in Rome around the tomb of Saint Agnes or of Saints Peter and Marcellin. In Tours, a cemetery developed around the basilica housing the tomb of Saint Martin as well as the settlements forming the vicus christianorum from the 6th century.1 Gradually, the spaces for the living and the dead became closer. In the 12th century, the medieval Christian cemetery was integrated into the urban fabric and often became a space where certain trade activities took place.2

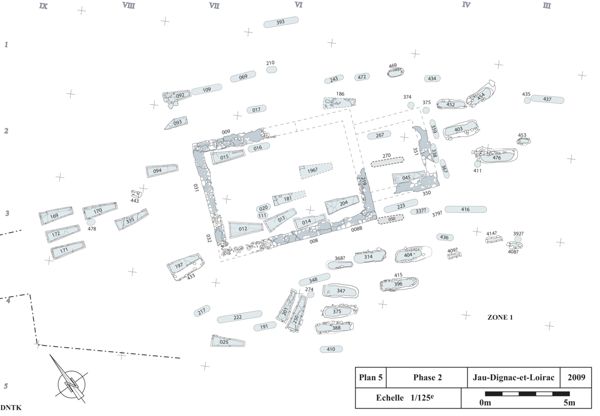

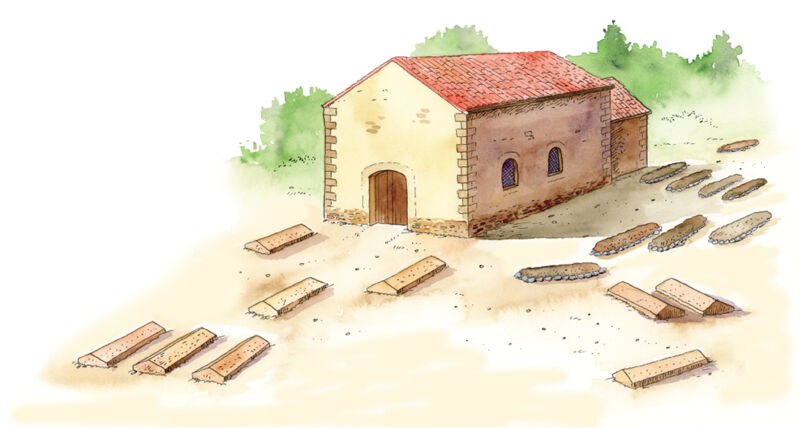

The evolution of burial spaces in the countryside is more complex and the hypotheses formulated have clearly evolved over the last twenty years.3 Although it was long thought that necropolises were distant from the habitat in the early Middle Ages and dissociated from the churches, the numerous recent archaeological discoveries – thanks to the large areas excavated in preventive archaeology and the new methods of approach in funerary archaeology – testify to a wide variety of situations. We can see that in early 5th-6th centuries, funerary spaces were located close to settlements, at Serris in the Paris region,4 and that there were also early churches associated with tombs. In addition, small groups of burials have often been uncovered; they are sometimes reserved for the elite, as at “La Tuilerie” in Saint-Dizier in the 6th century.5 These elites can also find ‘private’ spaces with a church, as at the site of “La Chapelle” at Jau-Dignac-et-Loirac near Bordeaux.6 In a short, recent research we can see that rural burial spaces are very varied, which is undoubtedly the result of the multiplicity of founders. Over the centuries, necropolises were increasingly associated with a church that polarized the cemetery. These churches, whose status was initially very diverse, were gradually integrated into a network controlled by the Church. As in the city, it was in the 11th-12th century that these Christian cemeteries were truly structured and became consecrated spaces, polarized around the parish churches, often located in the heart of the villages.7 Burial in the consecrated cemetery became essential for integration into the Western Christian community and for the salvation of the soul. Only bad Christians and criminals could fear not being buried there (see the text by M. Vivas below).

Read more

Pratiques funéraires et appartenances communautaires dans les sociétés médiévales à la lumière de l’archéologie et de l’histoire » (© Blois, Les rendez-vous de l’histoire. Les vivants et les morts, 10/2023).

References

- Alexandre-Bidon, D., 1998: La mort au Moyen Âge, XIIIe-XVIe siècle, Paris.

- Blaizot, F., 2017: Les espaces funéraires de l’habitat groupé des Ruelles, à Serris (Seine-et-Marne) du VIIe au XIe siècle, Thatan’os 4, Bordeaux.

- Cartron, I., 2015: “Avant le cimetière au village : la diversité des espaces funéraires. Historiographie et perspectives”, in: Treffort, C. (dir.), Le cimetière au village dans l’Europe médiévale et moderne, Actes des XXXVe journées de Flaran, Toulouse, p. 23-40.

- Cartron, I. & Castex, D., 2015: “Adaptation et transformation d’un cimetière du haut Moyen Age en milieu estuarien : le site de Jau-Dignac-et-Loirac en Gironde”, in: Gaultier, M., Dietrich, A. & Corrochano, A. (dir.), Rencontre autour des paysages du cimetière médiéval et moderne, Tours, p. 81-88.

- Lauwers, M., 2005: Naissance du cimetière. Lieux sacrés et terre des morts dans l’occident médiévale, Paris.

- Lauwers, M., 2015: “Le cimetière au village ou le village au cimetière ? Spatialisation et communautarisation des rapports sociaux dans l’Occident médiéval”, in: Treffort, C. (dir.), Le cimetière au village dans l’Europe médiévale et moderne, Actes des XXXVe journées internationales d’histoire de l’abbaye de Flaran, 11/12 octobre 2013, Toulouse, p. 41-60.

- Pietri, L., 1983: La ville de Tours du IVe au VIe siècle. Naissance d’une cité chrétienne, Rome.

- Truc, M.-C., 2019: Saint-Dizier, “La Tuilerie” (Haute-Marne) : trois sépultures d’élite du VIe siècle, Caen.