Introduction

In the last half century, great strides have been made in the archaeological sciences. Where we once relied upon macroscopic analyses, typological study, and visual characteristics, archaeologists now routinely utilize a variety of archaeometric methods to learn more about the production, trade, and use of various material culture items. Not all culture areas have been subjected to this same treatment, however. Until a decade ago, microscopic analyses in West Mexico were all but non-existent. Yet these empirical, replicable, and reliable methods couldn’t be more germane, particularly when it comes to the Aztatlán tradition and its expansive trade network that linked the American Southwest to Greater Mesoamerica1. The below study is a brief overview of geochemical analyses conducted in Western Mexico considering both lithics and ceramics. In the end, these analyses demonstrate not only the trade of goods across the region, but also the transmission of cultural ideas. While there is yet more to learn, this study provides a baseline for all future lithic and ceramic studies in the region, and demonstrates the utility of ever-evolving analytical technologies to better understand the human element of material culture in the past.

Background

Centered primarily on the coastal plain of Nayarit, Jalisco and Sinaloa (fig. 1), the Aztatlán Tradition reached its peak during the Early and Middle Postclassic Periods (AD 900-1350). The Aztatlán incorporated a number of Mesoamerican traits such as ball courts, open plaza configurations, codex style ceramics, and feathered serpent iconography2 into their sites. They are perhaps best known, however, for their widespread trade networks, which connected wide expanses through goods and ideas. Overall, the Aztatlán tradition was socially complex, but was likely not particularly organized politically. Rather, we see a “veneer” of commonality which simply supplemented existing local cultural traditions with an overlay of common Aztatlán traits3. In other words, this tradition was not centralized as a sociopolitical monolith, but was instead a loose conglomerate of partners who shared an array of cultural characteristics4 that were spread through the trade of both prestige and utilitarian goods5. This trade would have therefore been the catalyst for these “mutually understood ideological concepts and common symbolic grammar” that united people throughout the region6. These traits, such as Mazapan style figurines, the use of feathered serpent imagery, mound building, and distinct ceramic decorative styles have come to be known as the defining characteristics of the Aztatlán.

Coastal plain sites

The coastal plain features numerous large Aztatlán centers, each containing various examples of monumental architecture including large mounds, plazas, terraces, and ballcourts. The coastal plain in general was an ideal location for population growth due to the abundant resources available from multiple ecozones, as well as waterways that provided transportation corridors throughout West Mexico and beyond7. These critical waterways include the Marismas Nacionales, Rio Grande Santiago, Rio San Pedro Mezquital, and Rio Ameca. It is within this resource-rich region along the coastal plain of Nayarit that we find the core of the Aztatlán tradition. For this material culture study, five sites in total have been included from the coastal plain. The obsidian analysis included the sites of San Felipe Aztatán, Coamiles, Chacalilla, Amapa, and Peñitas. Of these, San Felipe Aztatán and Peñitas were also included in the ceramic analysis.

Located in Northern Nayarit, San Felipe Aztatán was one of the largest Aztatlán centers8. The site contains over 100 mounds and structures, the largest of which stands over nine meters in height9. The artifacts included here were collected as part of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) salvage excavations in 2002 that were conducted at four areas of the sites10. The site of Coamiles, on the other hand, was first recorded in the 1980s by archaeologists from École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS/Paris)11. This site is located along the alluvial plain and terraced slopes of the Cerro de Coamiles 60 km northeast of the modern-day city of Tepic. It has an overall size of at least 150 hectares and features clear indications of civic planning and formal architecture, including stone buildings12. It is also optimally located between the Rio San Pedro Mezquital and Rio Grande Santiago. Being between these two major waterways with similar access to marine resources to the west has prompted some to speculate that the community may have even controlled the main Aztatlán trade route to the Northwest, as well as the flow of goods across the coastal plain13. The artifacts included below were part of 2005-2009 INAH excavations led by M. Garduño Ambriz.

The third site under consideration is located near the modern town of San Blas. The site of Chacalilla spans nearly the entirety of a 2.4 km² volcanic hilltop. As is common with all Aztatlán centers, this site also had easy access to major waterways in the Rio Zauta and Marismas Nacionales. Also similar to other major Aztatlán settlements, Chacalilla contains abundant features, including at least 63 mounds, plazas, terraces, and even a ballcourt within the civic ceremonial center. All artifacts were collected during pedestrian surveys by M. Ohnersorgen14. Unlike all other sites, however, the obsidian provenance was established at this site through a combination of visual sourcing and geochemical analysis by Ohnersorgen15. Perhaps the most well-known of the Aztatlán sites, however, is Amapa. This major center was subject to large-scale excavations during the mid-20th century by C. Meighan and his University of California-Los Angeles students16. This famous site featured a number of architectural elements, burials, and material goods, including no less than 99 copper bells. Finally, though apparently not as significant as the other centers, Peñitas is located only 5 km north of Coamiles. It is split into two sectors (Peñitas A and B). Studies suggest that Peñitas B may have predated Peñitas A17, but differences in material culture may also reflect functional differences based upon the ceramic typology and burials18 and differences in architecture at the two sectors. Notably, several kilns have also been identified here, unequivocally indicating onsite ceramic production.

Etzatlán Basin sites

The Etzatlán Basin is the westernmost lake basin of the Jalisco highlands. Following the decline of the Teuchitlán (Shaft Tomb) Tradition (300 BC-AD 400), the area surrounding the now-drained Laguna de Magdalena grew in population into the thousands with dozens of communities surrounding the 235 km coastline19. Despite being far from the coastal plain, however, abundant evidence of coastal interaction has been observed here20. Notably, coastal Aztatlán style red-on-buff pottery has been observed at multiple Etzatlán sites21. Conversely, obsidian from the region east of the lake is also found in great abundance at coastal sites22 indicating some form of exchange between the regions. Though once supporting a large prehistoric population, the lake itself was drained in the second quarter of the 20th century23, with only residual stands of water left today24. Nonetheless, it was once an important region and population center that likely interacted with a number of different regions based upon their access to unique resources.

For the present study, the artifacts were originally excavated in the 1960s by S. Long and M. Glassow of the University of California- Los Angeles25. Though the collections featured over a dozen sites, the material was largely left unanalyzed in the decades that followed the excavations26 and now sits in storage at the UCLA Fowler Museum archives. For the below analysis, three sites were chosen based upon their location in relation to the lake. Located on the western edge of Laguna de Magdalena, Santiaguito also had an island component, and is near the narrowest constriction of the lake27. Here, looting has exposed material dating back to the Late Formative period, though Postclassic material is so abundant that it is yet found on the streets today as a result of modern land modification. Due to its location and size, it has been included in both obsidian and ceramic analyses. Huistla has similarly been considered in the analysis of both materials. It is located at the southern extent of the lake and was small in size. Its occupation dates back to the Shaft Tomb Tradition, but remained occupied into the Postclassic28. Notably, M. Glassow29 completed a stylistic analysis of Huistla ceramics previously, during which he identified several Aztatlán styles, suggesting possible importation from the coast. Finally, Atitlán (sometimes called Las Cuevas) was also included for ceramic analysis. Built upon an island on the eastern side of the lake with an abundance of resources nearby, this site was perhaps the most significant of the Etzatlán Basin sites, with a number of tombs and artificial caves, and even a possible I shaped ballcourt30. Previous studies have demonstrated the production and exportation of obsidian here from the La Joya source31. Given the already established La Joya production here, it was not included in the present obsidian analysis. However, ceramics stylistically related to the Lake Chapala region, the Coastal Plain, and the Rio Grande Valley have all been observed here as well as local types32. For this reason, Atitlán was chosen for inclusion in ceramic analyses.

Methods

These analyses were completed over multiple years. In total, the obsidian analyses took place over a five-year period from 2012 to 2017, at Centro INAH Nayarit in Tepic and at the Archaeometry Laboratory of the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR). A portable Bruker Tracer III-SD X-ray fluorescence spectrometer was used for data collection for each obsidian artifact and then compared to source samples curated at the MURR laboratory to establish provenance33. Sample sizes per site ranged from 900 to 5000 specimens. When entire assemblages from the sites were not analyzed, samples were selected based upon vertical and horizontal provenience and associations with other artifacts and features, for a total of over 14,000 obsidian artifacts analyzed. Regarding ceramics, approximately 80-100 sherds were collected from each of the five sites. Thirty raw clay samples were also collected for comparison from deposits in Jalisco and Nayarit, for a total of 452 total specimens being subjected to geochemical analysis. Pottery samples were selected based upon stylistic characteristics and context. All ceramic and clay samples were subjected to Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA) at MURR, and were prepared and irradiated per MURR’s standard protocol34. Following irradiation and data collection, raw elemental ppm counts were sent to the IRAMAT-CRP2A laboratory at the Université Bordeaux Montaigne for interpretation, using GAUSS multivariate statistical software. Finally, the study also included a geospatial component in the form of a Least Cost Path analysis, which was completed using ArcMap 10.3.1 software.

Results

Obsidian

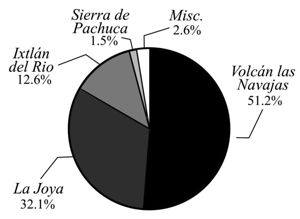

At the coastal sites in particular, results of the obsidian analyses indicate that three obsidian sources make up the majority of all obsidian used (fig. 2). The most proximal source is called Volcán las Navajas and is located approximately 35 km east of the coastal plain35. It is extremely common at all of the coastal sites, making up 51.2% of the entire assemblage. It is generally restricted to debitage as a result of percussion flaking, but perhaps also used for the production of expedient tools. Despite its high quality, accessibility, and abundance, it is rarely found in the form of prismatic blades and does not appear to have been controlled by any particular site or group of people. A second slightly further source, Ixtlán del Río, is also found in high numbers at all of the coastal sites (12.6% of all obsidian). This source is found in many forms, ranging from debitage, to formal tools, to prismatic blades. But though present, blades are yet infrequent. For prismatic blades, the preferred source was La Joya. In total, 75% of all coastal prismatic blades can be attributed to this source. In comparison to aforementioned common sources, the La Joya source is located much further inland in the Jalisco highlands near the Etzatlán Basin36, and represents 32.1% of the obsidian at the coastal plain sites. No lithic workshops have been identified at any of these coastal sites to date, but of the cores found, 78% of them are from La Joya as well. Given the frequency at which La Joya obsidian is found on the coastal plain and the fact that the source is located in the highlands just beyond the Laguna de Magdalena, it is clear that there was a connection between the two regions. It is also worth noting that 12% of the obsidian at San Felipe Aztatán (almost exclusively in the form of prismatic blades) was sourced to the important Sierra de Navajas (Pachuca) source in Central Mexico37. At no other site along the coastal plain has this source been identified with any frequency.

The results of analysis at the Etzatlán Basin sites revealed a pattern quite different than the coastal plain. Notably, at Santiaguito, the two western obsidian sources that were so common on the coastal plain (Volcán las Navajas and Ixtlán del Río) are completely absent. Instead, all of the obsidian found at Santiaguito originated from the highlands. Of the sample, 91% of all of the obsidian can be sourced to La Joya. Though La Joya obsidian is primarily found as prismatic blades on the coastal plain, at Santiaguito the La Joya obsidian is mostly in the form of debitage. This suggests that La Joya blade production may have taken place here with the finished products being exported westward.

The distribution of obsidian at Huistla, however, was in great contrast with that of the assemblage from Santiaguito. La Joya still makes up just over half of all obsidian here, but two other sources, Boquillas and Osotero, are also common (13% and 31% respectively). Notably, both of these sources could have been accessed directly from Huistla without crossing the large lake. Most formal tools in the assemblage came from Boquillas, just as most tools on the coast came from Ixtlán del Río. Meanwhile, most debitage is from Osotero, which is likely a result of domestic production of simply flaked tools in the same way coastal populations seem to have utilized Volcán las Navajas. Prismatic blades, on the other hand, are almost exclusively from La Joya, just like on the coast.

The hypothesis of exportation of La Joya obsidian is further supported through geospatial (GIS) analyses. If an individual were to walk directly from the coastal sites to the La Joya source in the most efficient route, they would pass nearby the Volcán las Navajas source and then Ixtlán del Río in Nayarit, before heading to the Etzatlán Basin and the Laguna de Magdalena that once filled it. There, the most efficient path crosses the lake near Santiaguito as well as Atitlán. This calculated path not only suggests that multiple obsidian sources may have been accessed by the same traders as they traversed the landscape, but also that Santiaguito and Atitlán may have been gatekeepers of sorts to La Joya obsidian. This would result in a larger amount of debitage at Santiaguito as the remains of reduction. Meanwhile, the proportion of blades may remain low there due to their removal from the site for exportation elsewhere. Based on these results, it appears that not only did Santiaguito possibly supply La Joya blades to the coast, but Santiaguito may have supplied obsidian blades to much of the Etzatlán Basin as well – made possible due to the prime location of the site to facilitate lake crossing.

Ceramics

Ceramic analyses were intended to further elucidate the relationship between the coastal plain and the Jalisco highlands (Etzatlán Basin). Specifically, were coastal styled ceramics in the highlands a result of trade, or were they produced locally through replication? The sites chosen for the ceramics study were based upon various factors. Peñitas was chosen due to the certainty of ceramic production there, after the detailed study of kilns on site38. San Felipe Aztatán, on the other hand, was chosen due to the aforementioned identification of Sierra de Pachuca obsidian. Its presence may be indicative of greater access to trade networks, given the distance to this source. Within the Etzatlán Basin, Huistla and Santiaguito were selected to better understand the intra-basin dynamics, given the different access to resources exposed through the obsidian analyses. Finally, Atitlán was chosen due to its location along the calculated Least Cost Path and its presumed participation trade.

The geochemical analysis of ceramics reveals several interesting results. First and foremost, there is a clear differentiation in paste composition between ceramics collected from the Etzatlán Basin and from those collected at the Coastal Plain (fig. 3A). This demonstrates that despite stylistic similarities, there does not appear to be any notable trade of ceramics between the two regions. Rather, it is far more likely that the coastal styled ceramics found in the Etzatlán Basin are in fact local imitations.

Comparing the two sites on the Coastal Plain, we see slightly different paste recipes with sherds from each site, indicating independent production. This is in contrast with what has been suggested in earlier analyses39. In a 2007 report produced at MURR, authors suggested that a large portion of the ceramics on the coastal plain were actually produced at a single site, Chacalilla, and then distributed from there. A reevaluation of that data suggests otherwise. In fact, with separate compositional signatures for San Felipe Aztatán and Peñitas, it appears that ceramics within the coastal plain were rarely traded even regionally. We do not see such differentiation between sites in the Etzatlán Basin, however. There is no single paste recipe that appears exclusive to one location. Rather, there are at least three major compositional groups, all of which can be found at each basin site (fig. 3B).

When considering raw clays, it is even clearer that coastal styled ceramics found in the highlands are not products of trade from the coast. Compositionally, the ceramics found in the highlands are more similar to highland clays, while coastal clays are more similar to coastal ceramics. The clays collected from Jalisco are not identical to ceramics collected there, but far more similar than those on the coast. As such, we cannot say for certain where the Etzatlán Basin ceramics were produced or where raw materials originated based upon reference samples alone, but we can say with certainty that they did not originate from the coastal plain, given the criterion of abundance40. With this premise, the fact that the same recipe groups are abundant throughout the basin, and are not found elsewhere, means that these ceramics were almost certainly produced somewhere in the vicinity and not imported from beyond the region.

At all three Etzatlán sites, we also see some notable correlations between compositional groups and decoration. At Atitlán, for example, a type known as Huistla polychromes is more likely to be made with the recipe A2. At the site of Huistla, on the other hand, incised and engraved ceramics are more likely to be a part of the broader A group, whereas strictly painted decorations are more common with other groups. At Santiaguito, Group A1 is mostly comprised of incised ceramics with red paint on interior and exterior surfaces. Though these correlations are not perfect, they are significant and indicate differential production where specific paste recipes may have been preferred for certain styles. Alternatively, these patterns may be a product of specific potter traditions in which different individuals specialized in specific styles.

Discussion and conclusion

Overall, this brief overview of archaeometric analyses in West Mexico reveals several key insights. First, there was a clear relationship between the major Aztatlán centers of the coastal plain and the Jalisco highlands. This is demonstrated by the obsidian analysis and further supported by the GIS Least Cost Path. While ceramics may not have been a part of this trade network, the existence of replication of coastal styles within the highlands demonstrates a familiarity with common design elements and a possible cultural affiliation between the two regions.

The obsidian analyses also revealed differential use of obsidian sources as each was utilized in specific ways. This is true in both the Coastal Plain as well as the Etzatlán Basin. In both cases, the most local sources were utilized for generalized reduction and at times formal tools. Meanwhile, one specific source, La Joya, was primarily used for the production of prismatic blades. Furthermore, direct access to this source may have been controlled by sites such as Santiaguito and Atitlán. Beyond this, results also show temporal patterns demonstrative of the ascent and subsequent decline of the Aztatlán trade network. Specifically, the more distant La Joya obsidian becomes common on the coastal plain during the Postclassic, coincident with the Aztatlán tradition zenith. Prior to this, the local source of Volcán las Navajas makes up the majority of the obsidian found, and blades were a rarity.

In contrast with obsidian, the trade of ceramics appears negligible, whether inter- or intra-regionally. Nonetheless, trade networks may have spread more than just material goods. Through long-distance interactions, ideas and cultural traditions were also spread with things like stylistic embellishments and even iconography to be used in the production of ceramics. This is evident through the regionally specific paste recipes identified through NAA. In instances where Basin sherds exhibit a style associated with the coastal plain, they yet appear to have been produced with a local paste recipe. Thus, while the obsidian analysis demonstrated physical trade between the regions, the ceramic analysis also shows the exchange of ideas and further demonstrates a purposeful integration into the Aztatlán tradition by the people of the Etzatlán Basin with shared ideas such as designs and styles.

In the past, it has been argued that the importation of obsidian into the coast may be an example of costly signaling41. At San Felipe Aztatán, we have a large amount of obsidian from the highly valuable Sierra de Pachuca source. Though this obsidian is functionally and qualitatively no different than local obsidians, it originates from a source over 600 km away. It is also associated with some of the most powerful cities in Mesoamerican prehistory, such as Teotihuacan and Tula. As such, elites may have acquired this more costly and exotic obsidian simply as a way to showcase their relationship with these powerful Central Mexican centers. The same principles may be at work in the replication of Aztatlán styles within the Etzatlán Basin. H. Neff42 has discussed this phenomenon in regards to the replication of Olmec greywares and Xochiltepc whitewares. He suggests that replica pots were used to signal affiliation and promote status. In the Etzatlán Basin, specific local craftsman may have similarly made local productions of Aztatlán style ceramics to tie themselves to the socioeconomically powerful coast. By showcasing this relationship, an individual could signal cultural, economic, and even political affiliation with powerful partners. As such, there may have been an incentive to utilize coastal styles, even if one could not access coastal goods directly. Regardless of the reason for it, however, there was a material and cultural affiliation between coastal and highland populations, which was likely driven by the Aztatlán trade networks.

There is yet much more to learn about material culture, trade, and production within the Aztatlán tradition and Western Mexico in general. But with the growing accessibility of various archaeometric methods, studies such as those described above will become increasingly more commonplace in the years to come. And with them, we will better our understanding of highland-lowland dynamics as well as the role trade played in the sociopolitical structures of pre-Columbian West Mexico.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible through the assistance and support of the following people, Mauricio Garduño Ambriz, Mike Mathiowetz, Michael Ohnersorgen, Todd VanPool, Christine VanPool, Tim Matisziw, Jeff Ferguson, Michael Glascock, Rodrigo Esparza, Susana Ramirez, Wendy Teeter, and Jasmine Pierce among others, as well as the following institutions, the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, The Fowler Museum of UCLA, the University of Missouri, IRAMAT-CRP2A of the Université Bordeaux Montaigne, and the MURR Archaeometry Laboratory. This project was supported in part by NSF grant #1912776 to the Archaeometry Laboratory at the University of Missouri Research Reactor, the Raymond Wood Excellence in Archaeology Fund, and l’Initiative d’Excellence de l’Université de Bordeaux.

References

- Bell, B. (1958): The Decorated Pottery of Peñitas. Seminar on Western Mexican Archaeology (Anthropology 169A), University of California.

- Bell, B. (1961): Analysis of Ceramic Style: A West Mexican Collection, doctoral thesis, University of California.

- Bishop, R., Rands, R., and Holley, G. (1982): “Ceramic compositional analysis in archaeological perspective”, in: Schiffer, ed. 1982, 275-330.

- Blanton, R., Feinman, G., Kabréowaleski, S., and Peregrine, P. (1996): “A Dual Processual Theory for the Evolution of Mesoamerican Civilization”, Current Anthropology, 37, 1-14.

- Bordaz, J. (1964): Pre-Columbian Ceramic Kilns at Peñitas, A Post-Classic site in Coastal Nayarit, Mexico, doctoral thesis, Columbia University.

- Brambila Paz, R.M., ed (1998): Antropología e Historia del Occidente de México, Memorias de la XXIV Mesa Redonda de las Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología, I, México City.

- Carpenter, J. (1996): El Ombligo en la Labor: Differentiation, Interaction and Integration in Prehispanic Sinaloa, Mexico, doctoral thesis, University of Arizona.

- Cecil, L., and Glascock, M. (2007): Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis of Pottery and Clay Sampled from Chacalilla, Nayarit, Mexico, technical report, Archaeometry Laboratory of the University of Missouri Research Reactor.

- Ciliberto, E. and Spoto, G., ed. (2000): Modern Analytical Methods in Art and Archaeology, New York.

- Corona Núñez, J. (1954): “Diferentes tipos de tumbas prehispánicas en Nayarit”, Yan (Ciencias Antropológicas), 3, 46-50.

- Duverger, C. (1998): “Coamiles, Nayarit: hacia una periodización”, in: Brambila Paz, ed. 1998, 609-628.

- Duverger, C. and Levine, D. (1993): Informe relativo a la exploración arqueológica del sitio de Coamiles, municipio de Tuxpan, estado de Nayarit, archaeological report, Centro INAH Nayarit.

- Folan, W., ed. (1985): Contributions to the Archaeology and Ethnohistory of Greater Mesoamerica, Carbondale.

- Foster, M. (1999): “The Aztatlán Tradition of West and Northwest Mexico and Casas Grandes: Speculations on the Medio Period Florescence”, in: Schaafsma & Riley, ed. 1999, 149-163.

- Foster, M. and Gorenstein, S., ed (2000): Greater Mesoamerica: The Archaeology of West and Northwest Mexico, Salt Lake City.

- Furst, P. (1965): “Radiocarbon Dates from a Tomb in Mexico”, Science, 147, 3658, 612-613.

- Gamez Eternod, L., and Garduño Ambriz M. (2003): Rescate Arqueológico CECYTEN, Plantel 06 San Felipe Aztatán, Municipio de Tecuala (Nayarit), technical report, Centro INAH Nayarit.

- Garduño Ambriz, M. (2006): Investigaciones arqueológicas en Cerro de Coamiles, Nayarit. Reporte técnico final de la primera temporada de campo (2005), technical report, Centro INAH Nayarit.

- Garduño Ambriz, M. (2007): “Arqueología de rescate en la cuenca inferior del río Acaponeta. Diario de Campo”, Boletín Interno de los Investigadores del Área de Antropología, CONACULTA-INAH, 92, 36-52.

- Garduño Ambriz, M. (2013): Análisis de Materiales de Excavación del Proyecto Arqueológico Coamiles (2005-2010). Reporte técnico del análisis cerámica/Temporadas 2007 y 2008, technical report, Centro INAH Nayarit.

- Garduño Ambriz, M., and Gamez Eternod, L. (2005): Programa Emergente de Rescate Arqueológico en San Felipe Aztatán, Municipio de Tecuala (Nayarit), technical report, Centro INAH Nayarit.

- Glascock, M. (1992): “Characterization of archaeological ceramics at MURR by neutron activation analysis and multivariate statistics”, in: Neff, ed. 1992, 11-26.

- Glassow, M. (1967): “The Ceramics of Huistla, a West Mexico Site in the Municipality of Etzatlán, Jalisco”, American Antiquity, 32, 64-84.

- Hirth, K. and Andrews, B., ed. (2002): Pathways to Prismatic Blades, Los Angeles.

- Jimenez Betts, P. (2018): Orienting West Mexico. The Mesoamerican World System 200-1200 CE, doctoral thesis, University of Gothenburg.

- Kelley, J.C. (2000): “The Aztatlán Mercantile System: Mobile Traders and the Northwestern Expansion of Mesoamerican Civilization”, in: Foster & Gorenstein, ed. 2000, 137-154.

- Long, S. (1966): Archaeology of the Municipio of Etzatlán, Jalisco, doctoral dissertation, University of California.

- Martinón Torres, ed. (2014): Craft and science: International Perspectives on archaeological ceramics, Doha.

- Mathiowetz, M. (2011): The Diurnal Path of the Sun: Ideology and Interregional Interaction in Ancient Northwest Mesoamerican and the American Southwest, doctoral thesis, University of California.

- Mathiowetz, M. (2018): “The Sun Youth of the Casas Grandes Culture, Chihuahua, Mexico (AD 1200-1450)”, KIVA, 84, 367-390.

- Meighan, C., ed. (1976): The Archaeology of Amapa, Nayarit, Monumenta Archaeologica 2, Los Angeles.

- Mountjoy, J. (2000): “Prehispanic cultural development along the southern coast of West Mexico”, in: Foster & Gorenstein, ed. 2000, 81-106.

- Nance, C.R., de Leeuw, J. and Weigand, P. (2013): “Introduction”, in: Nance et al., ed. 2013.

- Nance, C.R., de Leeuw, J., Weigand, P., Prado, K., and Verity, D. (2013): Correspondence analysis and West Mexico archaeology: ceramics from the Long-Glassow collection, Albuquerque.

- Neff, H. (1992): “Introduction”, in: Neff, ed. 1992, 1-10.

- Neff, H. (2000): “Neutron activation analysis for provenance determination in archaeology”, in: Ciliberto & Spoto, ed. 2000, 81-134.

- Neff, H. (2014): “Pots as Signals: Explaining the enigmas long-distance ceramic exchange”, in: Martinón Torres, ed. 2014, 1-12.

- Neff, H., ed. (1992): Chemical Characterization of Ceramic Pastes in Archaeology, Madison.

- Nielsen-Grimm, G. and Stavast, P., ed. (2008): Touching the past: ritual, religion, and trade of Casas Grandes, Provo.

- Ohnersorgen, M. (2004): Informe Técnico Final de Proyecto “Investigaciones Arqueológicas Preliminar de Chacalilla, Nayarit, México, technical report, Centro INAH Nayarit.

- Ohnersorgen, M. (2007): La organización socio-económica y la interacción regional de un centro Aztatlán: Investigaciones arqueológicas en Chacalilla, Nayarit. Informe, technical report, Centro INAH Nayarit.

- Perez, M., Gamez Eternod, L. and Garduño Ambriz, M. (2000): Proyecto de Salvamento Arqueológico “Entronque San Blas Mazatlán, tramo Nayarit”, technical report, Centro INAH Nayarit.

- Pierce, D. (2015): “Visual and Geochemical Analyses of Obsidian Source Use at San Felipe Aztatán, México”, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 40, 266-279.

- Pierce, D. (2016): “Volcán las Navajas: The chemical characterization and usage of a West Mexican obsidian source in the Aztatlán tradition”, Journal of Archaeological Science. Reports, 6, 603-609.

- Pierce, D. (2017a): Obsidian Source Distribution and Mercantile Hierarchies in Post Classic Aztatlán West Mexico, doctoral thesis, University of Missouri.

- Pierce, D. (2017b): “Finding Class in the Glass: Obsidian source as a costly signal”, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 48, 217-232.

- Pierce, D. (2021): “A Regional Assessment of Obsidian Use in the Postclassic Aztatlán Tradition”, Ancient Mesoamerica, 1-20.

- Pollard, H. (2000): “Tarascan External Relationships”, in: Foster & Gorenstein, ed. 2000, 71-80.

- Porcasi, J. (2012): “Pre-hispanic to Colonial Dietary Transition at Etzatlan, Jalisco”, México. Ancient Mesoamerica, 23, 251-267.

- Publ, H. (1986): Prehispanic Exchange Networks and the Development of Social Complexity in Western Mexico: The Aztatlán Interaction Sphere, doctoral dissertation, Southern Illinois University.

- Sauer, C., and Brand, D. (1932): Aztatlán: Prehistoric Mexican Frontier on the Pacific Coast, Ibero-Americana 1, Berkeley.

- Schaafsma, C.F. and Riley, C.L. (1999): The Casas Grandes World, Salt Lake City.

- Schiffer, M.B., ed. (1982): Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, V, New York.

- Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología, ed. (1979): Rutas de intercambio en Mesoamérica y el norte de México, XVI Reunión de Mesa Redonda, Saltillo, Coahuila, del 9 al 14 de septiembre de 1979, Saltillo.

- Soustelle, J. (1981): La zona arqueológica de Coamiles, Nayarit, technical report, Escuela de Altos Estudios en Ciencias Sociales (EHESS/Paris) y Centro de Estudios y de Investigaciones Antropológicas (Université de Lyon/III).

- Spence, M. (2000): “From Tzintzuntzan to Paquime: Peers or Peripheries in Greater Mesoamerica?”, in: Foster & Gorenstein, ed. 2000, 255-261.

- Spence, M., Weigand P. and Soto de Arechavaleta, M. de los D. (1979): “Obsidian Production and Exchange Networks in West Mexico”, in: Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología, ed. 1979, 357-361.

- Spence, M., Weigand P. and Soto de Arechavaleta, M. de los D. (2002): “Production and Distribution of Obsidian Artifacts in Western Jalisco”, in: Hirth & Andrews, ed. 2002, 61-79.

- Tenorio, D., Jiménez-Reyes, M., Esperaza-López, J.R., Calligaro, T.F. and Grave-Tirado, L.A. (2015): “The obsidian of Southern Sinoloa: New Evidence of Aztatlán networks through PIXE”, Journal of Archaeological Science. Reports, 4, 106-110.

- VanPool, T., VanPool, C. and Rakita, G. (2008): “Birds, Bells, and Shells: The Long Reach of the Aztatlán Trading Tradition”, in: Nielsen-Grimm & Stavast, ed. 2008, 5-14.

- Weigand, P. (1977): “Rio Grande Glaze Sherds in Western Mexico”, Pottery Southwest 4(1), 3-6.

- Weigand, P. (1985): “Considerations on the Archaeology and Ethnohistory of the Mexicaneros, Tequales, Coras, Huicholes, and Caxcanes of Nayarit, Jalisco, and Zacatecas”, in: Folan, ed. 1985, 126-187.

- Weigand, P.C. and Gwynne, G., ed. (1982): Mining and Mining Techniques in Ancient Mesoamerica, Anthropology 6, special issue, Stony Brook.

- Weigand, P.C. and Spence, M. (1982): “The Obsidian Mining Complex at La Joya, Jalisco.” in: Weigand & Gwynne, ed. 1982, 175-188.

Notes

- See Jiminez 2018; see VanPool et al. 2018.

- Carpenter 1996, 164-165, 253; Mathiowetz 2011, 10-11, 23-25; Mathiowetz 2018, 9-12.

- Foster 1999, 156; see Kelley 2000.

- Mountjoy 2000, 95-100.

- Blanton et al. 1996, 174-175; Publ 1986, 57-58, 171-178.

- Spence 2000, 259.

- Tenorio et al. 2015, 106; Kelley 2000, 141.

- See Garduño & Gamez 2005.

- Garduño 2007, 40; see Perez et al. 2000; Sauer & Brand 1932, 21-22.

- See Gamez & Garduño 2003; Garduño 2007, 38; see Garduño & Gamez 2005.

- See Duverger 1998; see Duverger & Levine 1993.

- See Soustelle 1981.

- See Garduño 2006; Garduño 2013, 7.

- See Ohnersorgen 2004.

- See Ohnersorgen 2007.

- See Bell 1961; see Meighan 1976.

- Pierce 2017a, 160.

- See Bell 1958; see Bordaz 1964.

- Porcasi 2012, 252.

- See Pollard 2000.

- Glassow 1967, 78-79.

- See Ohnersorgen 2007; see Pierce 2017a; Pierce 2017b, 221.

- See Weigand 1985.

- Porcasi 2012, 252.

- See Long 1966.

- For exception, see Glassow 1967; Porcasi 2012; Nance et al. 2013.

- Porcasi 2012, 253.

- See Corona Nuñez 1954; see Furst 1965.

- See Glassow 1967.

- Long 1966, 59-61, 298-304; Nance et al. 2013, 54.

- See Spence et al. 1979; Spence et al. 2000, 75-78.

- See Nance et al. 2013; see Weigand 1977; Weigand & Spence 1982, 186.

- For full description of methods see Pierce 2021, 6-7.

- See Glascock 1992; see Neff 1992; Neff 2000, 101-102.

- Pierce 2016, 603.

- Spence et al. 2002, 68; see Weigand & Spence 1982.

- Pierce 2015, 272.

- See Bordaz 1964.

- Cecil & Glascock 2007, 9.

- Bishop et al. 1982, 300-301.

- See Pierce 2017b.

- See Neff 2014.