This paper is the second1 in which we set out to re-evaluate what is known of the forts of that north-westerly outlier of Europe, Scotland. In this instance we have chosen to focus more particularly on the larger enclosed sites of the country, some of which have been assimilated from time to time2 with the oppida of southern Britain or the nearer continent. As Olivier Buchsenschutz did in his early studies of the enclosed sites of France, we have chosen to address this topic by taking a historical perspective, returning to some of the key early sources to give context to more recent work, and thereafter examining a basic parameter: site size. This study is necessarily very selective but we hope it illustrates the particular problems encountered in a country where more-or-less fortified enclosures are very numerous, generally small and, given the problems of radiocarbon calibration for the first millennium BC and the relative rarity of diagnostic artefacts, still often hard to date with anything like the precision usual on continental Europe. Inevitably, too, since the outset of their study, issues of complexity and potentially urban characteristics have been mixed in to the consideration of some of these sites, as has the use of oppidum as a term3.

The key Victorian pioneer in Scotland is David Christison who in 1885-1886, under doctor’s orders for exercise and plenty of fresh air, undertook a survey of the prehistoric forts and settlement earthworks of Peeblesshire4. Campaigns of fieldwork in other districts followed every summer thereafter, until he was invited to deliver in 1894 a lecture series on the subject to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. His initial intention had been to make comparisons with fortifications elsewhere in the British Isles and the Continent. In the event he found he had enough to do to survey the Scottish evidence, and, following his lectures, carried out two further seasons of fieldwork before publishing the series in a volume entitled Early Fortifications in Scotland5. Christison recognised that this was not a subject that could be treated ‘with scientific precision, that a strict and comprehensive classification is unattainable’6, and was well aware, that description and survey would not supply answers to his questions: ‘the secrets of the forts cannot thus be unlocked.’ he wrote, ‘This the pick and shovel alone can do’7. Nevertheless, his was the first systematic analysis of Scottish earthworks and fortifications, and, as we have observed8, his discussion of problems of definition remains worth reading as a model of good sense, particularly when it is considered how little was known about these monuments in his day. Beyond delineating some basic characteristics that allowed him to distinguish prehistoric enclosures from Roman and medieval works, he based his classification of forts upon four categories of size, ranging from ‘very small’ (no more than 30 m across) to ‘large’. These latter, which formed a relatively small proportion of his total, measured above c. 180 m in length by 90 m, thus enclosing areas in excess of 1.3 ha. In some respects little has changed since: Scottish prehistorians have intermittently struggled with problems of definition and the links between the components of the Scottish record and hillforts further afield in southern England, and indeed with oppida on the Continental mainland. Size, it seems, probably does matter, but what size, when and where?

History of research since Christison

Probably on the eve of the First World War, Alexander Curle passed a disparaging judgement on Christison’s efforts –‘We’ve had enough of old Christison, going round the forts measuring them up with his umbrella’, he told Angus Graham, ‘We must have more excavation’9– but a century later there is little to choose between them. Curle substituted a tape measure for the umbrella in his county surveys as Secretary (i.e. Director) of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, as indeed had others before him10, but his classification of Berwickshire earthworks hardly sets him apart11. In fairness to Christison, though much of his effort went into the Scottish Antiquaries’ programme of excavations at Roman fortifications, he also dug at several native forts. He examined Castlelaw, Abernethy, in Perthshire with Joseph Anderson12; Burnswark in Dumfriesshire13; Orchill and Kempy forts, again in Perthshire14; and several sites on the Poltalloch Estate in Argyll, famously including Dunadd15.

Curle also took up excavation, though his idea of what that entailed was not much more than a means to retrieve a collection of artefacts for typological study and dating16. On the back of his Royal Commission county surveys in south-west Scotland, he managed to excavate the early medieval fort known as the Mote of Mark overlooking the Urr estuary near Rockcliffe in the Stewartry17. He also cut some minor sections on Rubers Law18 and made some rather more extensive excavations19 on Bonchester Hill, both in Roxburgh. Having moved to become Director of the National Museum of Antiquities, he mounted a sustained campaign on Traprain Law in East Lothian, latterly with James Cree20. Had the first season yielded only the paltry scatter of artefacts and shallow stratigraphy typical of many Scottish fort excavations, he might not have persevered here, but the quantities of material from Late Bronze Age tools to Roman pottery and the well-known late Roman silver treasure21 cemented Traprain’s reputation as not only one of the largest forts in Scotland, but a first rank tribal caput that apparently resonated with the ancient fortifications of mainland Europe.

This is certainly one of the connections that Gordon Childe attempted to draw in The Prehistory of Scotland22, in which the assemblage from Traprain Law featured significantly in his synthesis of the Iron Age. This was one of seventeen ‘hilltop towns’ he proposed, though only fifteen of them are shown on his distribution map23, Burghead on the southern shore of the Moray Firth being classified as a Gallic Fort on the evidence of its timber-laced and nailed wall, while neighbouring Cademuir and White Meldon (‘White Melville’ in his text) in Peeblesshire were depicted by a single symbol. These ‘towns’ he defined as usually occupying the summits of isolated hills and enclosing an area of 10 acres (4 ha) or more, though in practice only four on his list attain this threshold. He was evidently struggling with his definition, but it is the contrast that he made between the more extensive enclosures on Traprain Law and Eildon Hill North on the one hand, and the proliferation of other small forts in southern Scotland on the other, that is more important than the absolute definition of the major sites. In the light of the artefacts and other evidence recovered by earlier excavations at Traprain Law, Bonchester Hill and Burnswark, and the comparisons he thus drew between these and the hillforts of southern England and Gaul, he himself did not examine this category of sites in his fieldwork but concentrated his efforts on the lesser forts. From the early 1930s until early in the Second World War he was responsible for excavations at no fewer than eight –including Earn’s Heugh in Berwickshire, Castlelaw, Glencorse, Midlothian, Finavon in Angus, Carminnow in the Stewartry, and Cairngryffe in Lanarkshire24. This was a remarkable achievement set against a figure of little more than twenty excavations at forts in the fifty years between Christison’s volume appearing and the campaign of excavation by the Piggotts and others in the late 1940s.

The Piggotts’ excavations were designed to create a series of regional type sites that had been investigated by modern excavation. Initiated at Hownam Rings in Roxburghshire25, these excavations (generally on small sites) also complemented the survey then underway in that county by the Royal Commission. Hownam Rings and Hayhope Knowe26 were chosen by an ad hoc committee consisting of Stuart Piggott, the Romanist Ian Richmond, Angus Graham and Kenneth Steer, these last two successive Secretaries (i.e. Directors) of the Royal Commission. These excavations, and the intellectual context in which they were developed, which envisaged a brief Iron Age of less than three centuries but marked by increasing social and political complexity, set the interpretative framework for the next forty years, and in his contribution to the Roxburghshire County Inventory Stuart Piggott described the fortifications on Eildon Hill North, Hownam Law and Rubers Law as oppida27. By then, this term seems to have come into common currency in Scotland to describe the largest of the fortified enclosures of the country. Richard Feachem, one of the Royal Commission investigators working on Roxburghshire, also wrote up a new survey of Traprain Law, and it is telling of the evolution of contemporary thought that in this account he uses hill-fort to describe the heavily robbed rampart enclosing 10 acres on the summit, as distinct from oppidum for the much larger enclosures of 30 (c. 12 ha) and 40 acres (c. 16 ha) taking in the lower terraces of this volcanic plug28 (fig. 1).

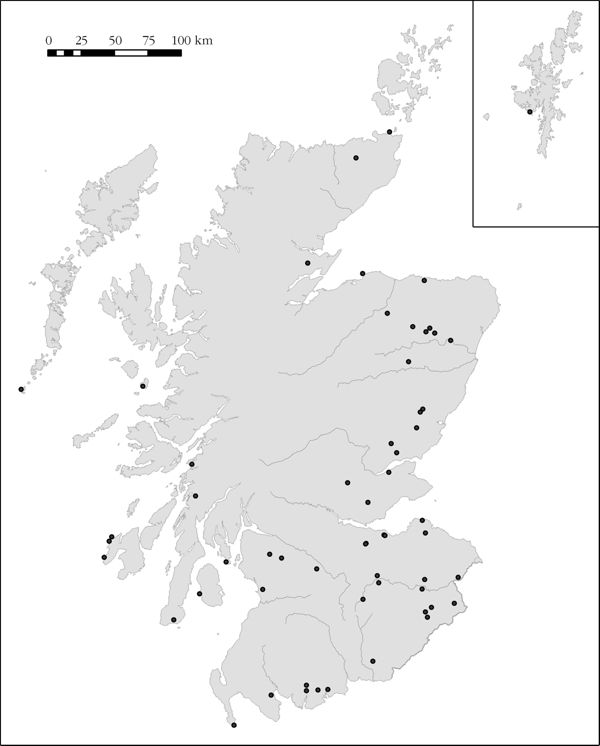

Informed by his central role in the extension of the Royal Commission fieldwork programme to the Border counties of Selkirkshire (1957) and Peeblesshire (1967), coupled with the wide-ranging Survey of Marginal Lands across the mainland of the country29, Feachem carried out the first systematic review of forts in Scotland since Christison. By 1963, he considered examples of the major enclosed sites of the country as ‘cities upon hills’30. Feachem’s key paper for our purposes was presented at an Edinburgh symposium in 1961, though not published until later31. By that date he or one of his Commission colleagues had visited the majority of the 1.500 forts and larger settlements then known in northern Britain, and he was in command of a mass of new information. This allowed him to recast the distinction between fort and oppidum that he had earlier drawn on Traprain Law. He now chose a threshold of 6 acres (2.43 ha) to define the lower limit of what he termed minor oppida, though the regional approach of his text and the correlations that he was attempting to make to tribes named by Ptolemy in the second century AD also necessitated the inclusion of a series of lesser forts of 4 or 5 acres (1.62-2.02 ha) which do not appear on the accompanying distribution map (fig. 2). Nevertheless, he depicted no less than twenty-four fortifications over 6 acres in extent, divided up with further thresholds at 10 acres (4.5 ha), 20 acres (8.09 ha) and 30 acres (12.14 ha). In terms of the areas selected, this was a different approach from that then taken for Southern Britain by the Ordnance Survey32, where the selected thresholds adopted in their map were 3 and 15 acres.

Based on firsthand knowledge of many of the sites, Christison had been the first to realise that the fortifications in his ‘large’ category were not disposed evenly across Scotland, mainly occurring in Lothian and the Borders, and nor were they proportionate to the total numbers of forts in the various regions. Thus, to take one extreme, he knew of only one out of the 164 forts he identified in Argyll, though this number is heavily inflated by the small structures that would now be classified as duns. In the lower Tweed Basin, however, it was 17 out of 164, while in eastern Scotland between the Forth estuary and the Moray Firth it was 15 out of 64. Although Childe’s33 selection of ‘hilltop towns’ was evidently highly subjective, and probably a measure of the limits of his own fieldwork, it broadly reflects this same uneven pattern, as does Feachem’s more rigorously selected map34. Indeed, this aspect of the distribution has not changed significantly with further fieldwork by, in particular, Ordnance Survey Archaeology Division (until 1983) and the Royal Commission, though notable additions include Hirsel Law in Berwickshire and Hill of Newleslie in Aberdeenshire, both discovered through aerial survey, and Doon Hill near Ringford in south-west Scotland, found through prospective fieldwork following up the indicative place-name. The most recent attempt to map the larger forts was carried out by the present authors, taking 2 ha as the lower limit for the larger forts35 (fig. 2). Based on existing records, this generates a total of fifty-seven examples, not substantially different from the figure of fifty for ‘large’ forts that Christison had arrived at. Geographically, however, the new map extends the distribution well beyond Feachem’s evidence36, albeit that the majority of sites still lie in the south and east of the country. At face value, however, it would seem that the essential differences in the distributions may simply lie in the slightly different area threshold that was chosen. The following case studies illustrate this issue.

Argyll and the Western Isles

While Feachem’s distribution in 1966 contained only one example in mainland Argyll, Cnoc Araich (2.5 ha) in Kintyre, continuing survey work by the Royal Commission for the County Inventory identified another three that attain the threshold he set –Dùn Ormidale (3 ha) in Lorn, and Creag a’ Chapuill (4 ha) and Sidhean Buidhe (7 ha) in Mid Argyll. Reducing the threshold to 2 ha, however, results in the inclusion of another five forts in the Inner and Outer Hebrides (below), while on mainland Argyll it is equally clear that there are other sites that fall just below the requisite size, and yet are significantly larger than any other enclosed sites in their locality. Dùn na Ban-òige (1.9 ha) serves as an example in Mid Argyll, while in Kintyre the outermost enclosure of Ranachan Hill might equally qualify (1.5 ha). In the Inner Hebrides, the island of Islay contains at least two sites that exceed 2 ha in extent –Beinn a’ Chaisteal (at least 3 ha) and Dùn Bheòlain (2.5 ha), both of them windswept rocky promontories on the island’s Atlantic façade, while Dùn Bhoraraig a little further down the coast is possibly a third example. Apparently there are no others in the Inner Isles, though Dùn na Faing on the same cliffs as Dùn Bhoraraig at 1.5 ha is not far short, while the inland fort revealed by cropmarks at Bridgend, also on Islay, is too of this order. These again are considerably larger than the typical small forts found throughout the island; even Borraichill Mór above Port Ellen, one of Childe’s ‘hilltop towns’37, encloses an area of only 0.76 ha.

This pattern is revealed almost as starkly on the island of Mull, where there are none of 2 ha, but the fort cutting off an area of only 1 ha on the rocky coastal promontory of Sloc a’ Mhuilt dwarfs most of the other enclosed sites on that island, which are typically between 0.05 ha and 0.15 ha in extent38. Indeed, a rough calculation of the areas of the 158 forts contained in the County Inventory for Argyll reveals that 80 % fall below 0.3 ha in extent. If the 305 small defensive structures known as ‘duns’ –most of them simply fortified buildings– are added into the totals, this figure rises to no less than 94 % of all Iron Age fortifications, 84 % of them enclosing less than 0.1 ha. The emphasis here is clearly on very small fortified places. The spread of sizes rapidly diminishes thereafter and only ten examples fall between 0.4 ha and 0.6 ha. The seven forts between 1 ha and 2 ha in Argyll (including its off-shore islands) are thus almost as unusual as the much larger fortified enclosures that have been discussed already (supra).

Reliable data is more difficult to obtain for the Outer Hebrides, the islands lying out across the broad expanse of The Minch off the north-west coast of Scotland and generally referred to now as the Western Isles. Nevertheless, as far as forts are concerned, it seems likely that a similar pattern dominated by very small sites occurs here. The only example that truly breaks the 2 ha threshold is on Mingulay. Eponymously named Dùn Mingulay, this is yet another rocky coastal promontory, though in this case most spectacularly situated on precipitous cliffs some 200 m high on the Atlantic coast of the island (fig. 3). A short length of wall sited on the seaward side of the narrow neck linking the promontory to the rest of the island utilises the naturally defensive qualities of the rock outcrops to cut off no less than 8.5 ha, an enclosed area out of all proportion to the island itself, which extends to only 6 sq km.

When the present writers prepared their previous map there was cause to debate the results of surveys on Lewis, the northernmost of the Western Isles, which had raised the possibility that there might be other examples of large Iron Age promontory enclosures along –in particular– the Atlantic façade39. They included Tolsta Head, a headland of 70 ha on the east coast of Lewis, which would have far outstripped the otherwise exceptional headland enclosure of 55 ha occupying the Mull of Galloway, the south-western tip of Scotland, to become the biggest enclosed site potentially of later prehistoric date in Scotland. These enclosures were omitted in our 2009 article until more information was forthcoming. Since then it has proved possible for one of the authors (SH) to visit seven of the enclosures identified in those surveys, and another eight examples have been reviewed using orthorectified aerial photographs to gauge their character and extent. As the authors of the report on the coastal surveys realised, promontories and headlands were often enclosed in the post-medieval period to manage grazing livestock, variously to keep the beasts off some dangerous parts of the cliffs and to pen them on other headlands. Of the seven coastal promontories visited, six are considered to be such livestock enclosures, including the massive Tolsta Head; they were mainly delimited by turf-built walls. Such boundaries are easily distinguished on the ground, comprising low spread banks no more than 2 m in thickness and perhaps 0.5 m in maximum height, flanked by shallow hollows on one or both sides where the turf has been stripped for their construction. Furthermore, in all but one case, the boundaries were placed on the landward side of natural gullies forming the promontory necks and thus did not exploit the natural defensive qualities of the topography. To make the comparison with one that is certainly a fortification on Dùn Dubh, near Sheshader, on the Isle of Lewis, here the single wall cutting off the promontory is set on the steep seaward side of the neck, linking the cliffs to either side and forming a spread of rubble still 3 m in thickness and up to 1.7 m high on the slope. Although claimed to be between 2 ha and 3 ha, measurement from the orthorectified photographs indicates that there is a maximum of 1.5 ha of usable space on the domed summit of the promontory. Dùn Dubh thus fails to measure up to the 2 ha threshold, but it is clear from fieldwork across a range of other promontory forts on Lewis that its size is exceptional on that island. By and large the typical promontory fort in the Western Isles is no bigger than that of Argyll. Another large example can be seen at Dùn a’ Bheirgh, on the west coast of Lewis north of Carloway, where a rocky promontory behind a thick wall and two outer ramparts extends to about 1.25 ha, while a speculative visit to a promontory just north of Port Ness in the far north of the island has turned up another of some 1.3 ha.

Eastern Scotland south of the Moray Firth

The contrast to either side of the mountainous spine of Scotland is not limited to its scenery. The character of the archaeological record changes significantly: the drystone architecture of the small fortifications set on knolls and promontories along the indented Atlantic seaboard is largely missing. The east as described in this case study presents an open landscape of farms and fields, and while it has a coastline of some 250 km from Burghead on the southern shore of the inner Moray Firth east of Inverness round to the mouth of the Firth of Tay, the whole emphasis of prehistoric settlement lies in the arable hinterland, where cropmark aerial photography has revealed large numbers of Iron Age settlements. These are apparently dominated by unenclosed round-houses, occurring singly and in clusters, and often constructed mainly in timber. While this form of settlement is present in Atlantic Scotland (e.g. from the later Bronze Age at Home Farm, Portree, Skye), it is largely invisible, mainly because the cropmark record is very limited in those environments. In addition to unenclosed round-houses, in eastern Scotland the cropmark record also provides evidence of enclosed settlements bounded by ditches or palisades, but in contrast to the south-east of the country, south of the Firth of Forth, such small enclosed sites in the present arable zone form a relatively minor component of the Iron Age settlement record40.

The distribution of forts, furthermore, is both comparatively thin and uneven41, with about seventy-five known in total from the southern shore of the Moray Firth south to the banks of the Tay. As might be expected with such a long coastline, several occupy promontories, but by far the majority lie inland. The coastal promontory forts tend to be relatively modest enclosures, but they include Burghead, where a set of multivallate defences delimits an area in excess of 2 ha on a large elevated headland which includes the elaborate ‘Gallic’ fort, mentioned above, and now known to be Early Historic in date. Remarkably, this is one of no less than fifteen fortifications that cross this threshold, representing 18% of the total regional sites, and thus marking a considerable contrast with the 6 % of this size noted along the Atlantic coastlands. But here we see the unevenness of the distribution, for in the north-eastern corner, north of the mountain barrier of The Mounth (where the Highland edge reaches the North Sea to the south of Aberdeen), where there are a little over thirty forts of all sizes, no fewer than ten are over 2 ha, representing 30 % of this subset. The forts making up this group, however, are disparate in their topographic settings and enclosing architecture, ranging from the stone-walled enclosure of 16 ha containing numerous circular house-platforms on Tap o’ Noth in Aberdeenshire, to the minor bank and ditch forming a featureless enclosure of 5 ha on the Hill of Newleslie, or the earthen rampart and ditch taking in 2.1 ha at Dunnideer42. Two of these sites, once considered as ‘unfinished’43, rather give the appearance of having been enclosed at some stage by palisades, namely on Little Conval (2.1 ha) and Durn Hill (2.6 ha).

Similar contrasts can be found south of The Mounth in Angus and Perthshire, for example in the complex sequences of defences on the White (6 ha) and Brown (5.5 ha) Caterthuns compared with the single rampart on Kinpurney Hill (7 ha), with its deeply inturned entrance apparently aligned upon the distant peak of Schiehallion44, a mountain whose place-name preserves the ancient name of the Caledones45. And again there are examples of enclosures that probably only just qualify in size terms, such as the outer fort on Dunsinane Hill, Perthshire. In contrast to the large fortifications in Atlantic Scotland, there is much more evidence that these enclosures form stages in sequences of construction on their sites. The most complex example of this examined to date is the Brown Caterthun46. On the ground this displays at least four separate lines of enclosure in its earthworks, and excavation has now revealed something of their complexity and dates. In short the small innermost bank enclosing 0.4 ha seems to be the remains of a palisaded enclosure dating from 350-50 cal BC, which was inserted into the interior of a multivallate fort of 2.1 ha. This latter, which was constructed before 400 cal BC, was possibly succeeded by the inner of the outermost pair of ramparts of a larger enclosure, though this too dates from before 400 cal BC. The interior of this enlarged fort extended to some 5,5 ha, and at some point between 400 and 200 cal BC the outermost rampart was also added47. The White Caterthun, on the opposing nearby summit across a shallow saddle, arguably represents additional stages in this sequence, in which there is not only a major stone fortification enclosing 0.7 ha on the summit, but also at least two phases of an outer fortification of some 6.7 ha, one of which was a palisade48.

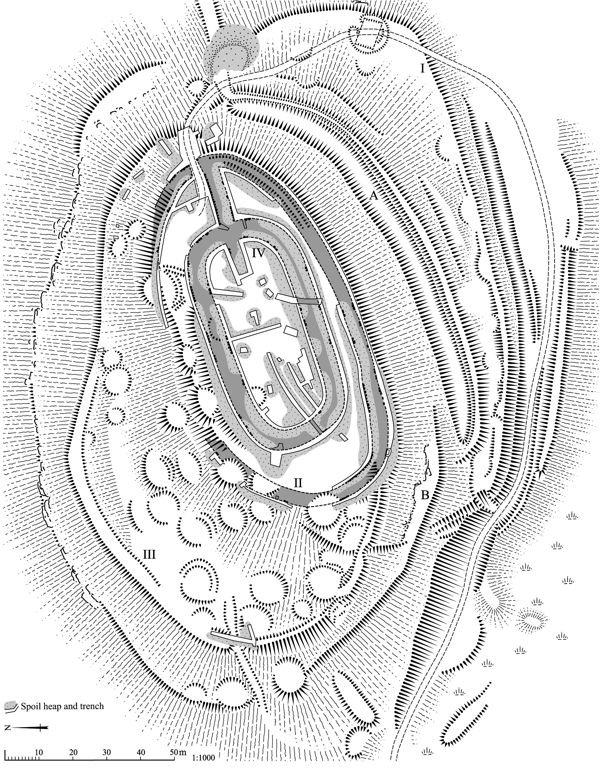

By Scottish standards, the stone summit fort of the White Caterthun is particularly massive in its construction, and is one of a distinctive series of comparatively small stoutly constructed forts49, some of which made up elements of Childe’s Abernethy complex50. He named this after Castlelaw, Abernethy, in Perthshire, originally published by Christison and Anderson51, which stands high above the River Earn where it debouches into the Tay estuary. Together with the inner fort at Burghead and Castle Law, Forgandenny (0.1 ha), the latter only a short distance west of Abernethy, at the time that Childe was writing this was one of only three where evidence of beams and timberwork had been found in the walls, leading him to style them Gallic Forts52. While there is some variation in plan, and possibly in date, most of this series are at the very least oblong on plan, and some are markedly lozenge-shaped. They generally lack evidence for an entrance. Taking Burghead to mark a variant at the north-west extremity of our north-eastern sample, others are found in Aberdeenshire on Tap o’Noth (0.3 ha) and Dunnideer (0.1 ha), in former Kincardineshire at Green Cairn, Balbegno (0.1 ha), in Angus at Finavon (0.3 ha) and Turin Hill (0.5 ha), and in Perthshire on Barry Hill (0.2 ha) and Dunsinane Hill (0.1 ha). While none of these remotely approaches the 2 ha threshold, with the notable exception of Finavon they all lie within larger, usually much larger, fortification systems. And here some of the reservations that emerged in the discussion of the Atlantic forts also come to the fore. Is it the absolute size threshold that is important, or simply the repetition of the positioning of these oblong stone (often vitrified) forts into larger enclosures that is more telling? At Barry Hill, for example, the first line of its outer works encloses only 0.8 ha, while an irregular wall linking steep scarps and outcrops outside this extends to 1.7 ha. The same commentary applies at Castle Law, Forgandenny, which has been surveyed recently by the Royal Commission (fig. 4a/b). The earlier defences here represent at least three other periods of construction, variously enclosing 0.4 ha, 0.9 ha and 1 ha respectively, and though the very outermost line possibly takes in as much as 1.7 ha, it still does not qualify as a major fort on the size threshold that we have taken for our distribution map.

One element that clearly informed Childe’s concept of a ‘hilltop town’ was topographical position which, in view of the disparate character of the major forts he included in this category, was perhaps the overriding factor in his thinking. A dominant setting remains a potent if unquantifiable characteristic, for like so many other large forts in north-eastern Scotland, Barry Hill and Castle Law, Forgandenny both occupy locally conspicuous hills. Whatever the functions of the large forts, and excavation at the Brown Caterthun has certainly challenged any notion of a town in the manner that Childe conceived, these were all places of significance in the Iron Age landscape, and it seems likely that discriminating between Turin Hill at 2.8 ha and Castle Law, Forgandenny at 1 ha simply on the basis of the area that they enclose does not really get to grips with the nexus of problems that these sites represent. To translate this commentary back into Aberdeenshire, where the distribution of forts is in any case much thinner, it would seem unlikely that Barra Hill and the Barmekin of Echt, both of which display an earlier phase enclosing 1.5 ha and a later phase of about 0.9 ha, are any less significant in their local Iron Age landscapes than Bruce’s Camp at 2.5 ha, or Dunnideer at 2.1 ha.

Discussion and conclusion

At various times it has proved tempting to try to see the major forts of Scotland –here taken as those above 2 ha in extent– as part of more widespread phenomena. For the inter-War and post-War generations of archaeologists in Scotland, with their wider geographical horizons and their continuing familiarity (cf ‘Gallic forts’ above) with Classical texts such as Caesar’s de Bello gallico, the recasting of Childe’s concept of ‘hilltop towns’ as minor oppida, and thus northern and late outliers of the continental series and their southern British (as far north as Stanwick, Yorkshire) variants seemed compelling. Thus relatively large-scale sites were envisaged as tribal centres close in date to the Roman advance, within whose occupation increasing signs of complexity might be envisaged. Some Scottish sites may indeed, as has been evident since the 1920s at Traprain Law53, have been occupied into the Roman Iron Age and display at that time some of the characteristics of oppida much further south54. In other cases, evidence of late use –here meaning approximately concurrent with the extension of the Roman Empire into Scotland– is less extensive: Burnswark at the foot of Annandale –with its supposed Roman siegeworks– is the celebrated example. Are the latter the tokens of a Scottish Alesia, or simply of a frontier garrison’s peacetime training against an abandoned and decaying native fort55? In general, the ‘minor oppida’ model has never entirely disappeared, finding expression anew in Harding’s synthetic pieces56 or in the introductions to more general works on medieval urban life in Scotland57.

In more recent studies, again predominantly drawing on evidence from sites in south-east Scotland in the core of Piggott’s Tyne-Forth province58, radiocarbon and other evidence has been marshalled59 to make the case that in some instances major fortified enclosures may rather be a characteristic of the Late Bronze Age / Early Iron Age transition phase, in the centuries around 800 BC, than a later period, although at Traprain Law itself there seems reason to consider that the earlier lines of enclosure may be more recent than the more intensive Late Bronze Age occupation. This hypothesis also cannot be gainsaid, although how widely it may be applicable across Scotland is also uncertain.

There is also the possibility that some of the Scottish sites we have mapped may be entirely de novo constructions of the first millennium AD, as can be argued, although not incontrovertibly –we have presented an alternative reading of the field evidence above– for Burghead60. Furthermore, in many cases, and in some despite exploratory excavation –as in the biggest site in Scotland, the major promontory jutting into the Irish Sea at the Mull of Galloway, we simply have no dating evidence whatsoever for their use.

Adopting a particular size threshold (in our case 2 ha) as a cut-point in site distributions across even as small an area as Scotland may be contentious, and studying regional variations in the sizes of sites present may be a better proxy from which to develop hypotheses. None the less we hope to have demonstrated that these larger sites –in a country where most enclosed Iron Age sites are in European terms diminutive– are more common and more widely distributed across the country than previous commentators have suggested. Further, that in at least a few areas they are proportionately of considerable significance in relation to total numbers of enclosed sites. And lastly, variabilities in fortification styles and sequences and dating evidence, where excavation evidence is available, as is shown by the case studies rehearsed above, make it resolutely clear that no single explanation nor chronological horizon can claim satisfactorily to include them all.

Appendix: principal references to forts mentioned in the text

Each site is given with its current administrative region (e.g. Perth & Kinross: rather than the county names standardly used), its record number in Canmore (the RCAHMS on-line database: rcahms.gov.uk) (e.g. NO11NE 12) and the most recent principal references containing a description and/or plan. In most cases the name entered into the Search Box on the first page of the RCAHMS website will lead to the record, but where this name has been applied to multiple records, the record number entered into the first two boxes of the ‘Where’ section of the ‘Advanced Search’ facility in Canmore will lead directly to the record, which may contain a range of further references in addition to brief descriptions, plans and photographs.

Barmekin of Echt, Aberdeenshire NJ70NW 1: Simpson 1920; Halliday 2007, 97-100.

Barra Hill, Aberdeenshire NJ82NW 4: Halliday 2007, 97-100.

Barry Hill, Perth & Kinross NO25SE 23: RCAHMS 1990, 27-9.

Beinn a’ Chaisteal, Islay, Argyll & Bute NR27SW 5: RCAHMS 1984, n°131.

Bonchester Hill, Scottish Borders NT51SE 10: C. M. Piggott 1950; RCAHMS 1956, n°277

Borraichill Mór, Islay, Argyll & Bute NR34NE 11: RCAHMS 1984, n°134.

Bridgend, Islay, Argyll & Bute NR36SW 24: RCAHMS 1984, n°136.

Brown Caterthun, Angus NO56NE 1: Dunwell & Strachan 2007.

Bruce’s Camp, Aberdeenshire NJ71NE 3: Halliday 2007, 97-100.

Burghead, Moray NJ16NW 1: www.ianralston.co.uk/projects or Ralston 2004.

Burnswark, Dumfries & Galloway NY17NE 2.00: Jobey 1978; RCAHMS 1997, 129-30, 179-82; Keppie 2009.

Cademuir, Scottish Borders NT23NW 13: RCAHMS 1967, n°263.

Cairngryffe, South Lanarkshire NS94SW 11: Childe 1941; RCAHMS 1978, n°220.

Carminnow, Dumfries & Galloway NX69SW 8: RCAHMS 1914, n°87; Childe 1936, 341-7.

Castle Law, Forgandenny, Perth & Kinross NO01NE 5: Bell 1893; Christison 1900, 74-6, Feachem 1966.

Castlelaw, Abernethy, Perth & Kinross NO11NE 12: Christison & Anderson 1899; Christison 1900, 76-9; Feachem 1966, 66-8, 75 fig. 5.

Castlelaw, Glencorse, Midlothian NT26SW 2: Childe 1933; Piggott & Piggott 1952.

Cnoc Araich, Kintyre, Argyll & Bute NR60NE 2: RCAHMS 1971, n°161.

Creag a’ Chapuill, Mid Argyll, Argyll & Bute NM80SE 16: RCAHMS 1988, n°243.

Doon Hill, Ringford, Dumfries & Galloway NX65NE 26.

Dùn a’ Bheirgh, Lewis, Western Isles NB24NW 2: RCAHMS 1928, n°12; Burgess 1999, 93.

Dùn Bheòlain, Islay, Argyll & Bute NR26NW 6: RCAHMS 1984, n°144.

Dùn Bhoraraig, Islay, Argyll & Bute NR15NE 14: RCAHMS 1984, n°145.

Dùn Dubh, Sheshader, Lewis, Western Isles NB53SE 1: Burgess 1999, 95, 98.

Dùn Mingulay, Mingulay, Western Isles NL58SW 1: RCAHMS 1928, n°452.

Dùn na Ban-òige, Mid Argyll, Argyll & Bute NM80SW 15: RCAHMS 1988, n°253.

Dùn na Faing, Islay, Argyll & Bute NR15NE 3: RCAHMS 1984, n°155.

Dùn Ormidale, Lorn, Argyll & Bute NM82NW 15: RCAHMS 1975, n°137.

Dunadd, Argyll & Bute NR89SW 1.00: Lane & Campbell 2000.

Dunnideer, Aberdeenshire NJ62NW 1: Halliday 2007, 97-102.

Dunsinane Hill, Perth & Kinross NO23SW 1: RCAHMS 1994, 55-7.

Durn Hill, Aberdeenshire NJ56SE 4: Feachem 1971, 27-8.

Earn’s Heugh, Scottish Borders NT86NE 8: RCAHMS 1915, n°80; Childe & Forde 1932.

Eildon Hill North, Scottish Borders NT53SE 57: RCAHMS 1956, n°597; Owen 1992.

Finavon, Angus NO55NW 32: Childe 1935b; Alexander 2002.

Green Cairn, Balbegno, Aberdeenshire NO67SW 1: Wedderburn 1973.

Hayhope Knowe, Scottish Borders NT81NE 18: C. M. Piggott 1949; RCAHMS 1956, n°665.

Hill of Newleslie, Aberdeenshire NJ52NE 31: Halliday 2007, 98, 103.

Hirsel Law, Scottish Borders NT84SW 7.

Hownam Law, Scottish Borders NT72SE 10: RCAHMS 1956, n°299.

Hownam Rings, Scottish Borders NT71NE 1: C. M. Piggott 1948; RCAHMS 1956, 160-1, No. 301.

Kempy Fort, Drumharvie, Perth & Kinross NN92SE 1: Christison 1900, 119-20; idem. 1901, 37-8.

Kinpurney Hill, Angus NO34SW 7: Ralston 2006, 41.

Little Conval, Moray NJ23NE 1: Feachem 1971, 28.

Mote of Mark, Dumfries & Galloway NX85SW 2: Laing & Longley 2006.

Mull of Galloway, Dumfries & Galloway NX13SW 17: RCAHMS 1912, n°148.

Orchill, Perth & Kinross NN81SE 2: Christison 1900, 117-19; idem. 1901, 21-3.

Ranachan Hill, Kintyre, Argyll & Bute NR62NE 12: RCAHMS 1971, n°173.

Stratford Halliday and Ian Ralston, april 2022

Recent years have seen the completion of the Atlas of the Hillforts of Britain and Ireland project, which incorporates records for some 1481 confirmed hill- and promontory-forts in Scotland. The criteria for the inclusion of individual sites are contained in the freely-accessible online resource (Lock and Ralston 2017), which also includes information on every confirmed hillfort. These criteria are also discussed by Lock (2019, 4-7) and in Lock and Ralston (2022).

Lock and Ralston (2022, 101-139) provide an extensive discussion of hillfort internal area sizes across Britain and Ireland. This includes numerous maps which depict the Scottish evidence in relation to that from the remainder of the British Isles. For example, Fig. 4.16 displays the 762 hillforts between 1 and 4.99 ha in extent: of these, 138 (c. 18%) are in Scotland.

Of the sites specifically named in the article, there has been further research on several. In almost all cases this consists of small-scale excavation, with the resultant chronology heavily dependent on limited numbers of radiocarbon determinations. Supporting artefactual evidence is markedly rare. In what follows sites are considered alphabetically and numbers thus [xxxx] indicate the entry in the online Atlas (Lock & Ralston 2017), where further information and recent bibliographic references are available.

At Barra Hill [2981] small excavation trenches indicate the development of successive enclosures during the pre-Roman Iron Age, with, more tentatively, evidence for Early Medieval re-use. Further excavations at Burghead directed by Professor Gordon Noble (Ravilious 2021) have provided extensive evidence for Early Medieval occupation and have confirmed the existence of burnt longrines set in the inner face of the fortification wall at the seaward end of the promontory. Investigations in the immediate vicinity of Burnswark [0890] have strengthened the evidence for a Roman assault on the site (Reid and Nicholson 2019). As part of the Hillforts of the Tay project, small-scale work on the enclosure and interior of Castle Law, Abernethy [3030] (Cook, Martin and McLaren 2020) confirmed the elaborate timber-lacing of its walls; artefacts and other evidence recovered indicates a pre-Roman occupation. The examination of Castle Law, Forgandenny [2994] by a University of Glasgow team provided evidence both for vitrification of the inner wall and of another complex bank (SERF, n.d.). Charcoal recovered from under tumble associated with the vitrified wall at Dunnideer [2959] produced later first millennium BC determinations (Cook and Murray 2010) At Durn Hill [2958] one of the palisade lines has furnished a radiocarbon date attributable to the Early Iron Age before 400 BC (Noble et al. 2020). Noble has dated the outer rampart at Tap o’ Noth [2938] to the Pictish period, thus placing the external enclosure of this substantial fort in the first millennium AD (Rideout 2021). The enclosure of the bivallate fort on Turin Hill [3084] has been attributed to the Early Iron Age on the basis of a single radiocarbon date for an occupation layer sealed below the rampart core (O’Driscoll and Noble 2020, Table 1). This newer evidence does not require the conclusions reached in the original article to be substantially revised, although the dating of individual sites has been clarified. Some of the enclosing works around the larger hillforts of Scotland may indeed date to the Late Bronze Age / Early Iron Age transition. Turin Hill may be, exceptionally, a bivallate case of this series, but evidence to sustain this hypothesis is meantime limited. Other examples seem to belong later in the Iron Age surviving up to – as at Burnswark – or even into the Roman Iron Age. Castle O’er, Dumfriesshire {1103], not specifically considered in the original article as somewhat smaller in extent, offers a variation in the addition of a more slightly-enclosed annex to the main hillfort (Mercer 2018). The outer enclosure at Tap o’ Noth represents the most spectacular addition to the case for first millennium AD major forts in Scotland. Excavation work elsewhere, notably on the skirts of East Lomond Hill, Fife – a site not specifically covered in the original paper [3120], intimates that there may be further mid-first-millennium AD major enclosures in Scotland awaiting identification.

References

- Alexander, D. (2002): “An oblong fort at Finavon, Angus: an example of the over-reliance on the appliance of science”, in: Ballin Smith & Banks, dir. 2002, 45-54.

- Alexander, D. and I. Ralston (1999): “Survey work on Turin Hill, Angus”, Tayside & Fife Archaeological Journal, 5, 36-49.

- Armit, I. (1997): Celtic Scotland, London.

- Ballin Smith, B. and I. Banks, dir. (2002): In the shadow of the Brochs: the Iron Age in Scotland, Stroud.

- Bell, A. S., dir. (1999): The Scottish antiquarian tradition, Edinburgh.

- Burgess, C. (1999): “Promontory Enclosures on the Isle of Lewis, the Western Isles, Scotland”, in: Frodsham et al., dir. 1999, 93-104.

- Burgess, C. and M. Church (1997): Coastal Erosion Assessment (Lewis), Edinburgh.

- Childe, V. G. (1933): “Excavations at Castlelaw Fort, Midlothian”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 67, 362-388.

- Childe, V. G. (1935a): The Prehistory of Scotland, London.

- Childe, V. G. (1935b): “Excavations of the Vitrified Fort of Finavon, Angus”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 69, 49-80.

- Childe, V. G. (1936): “(1) Carminnow Fort; (2) Supplementary Excavations at the Vitrified Fort of Finavon, Angus; and (3) some Bronze Age Vessels from Angus”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 70, 347-352.

- Childe, V. G. (1941): “Examination of the Prehistoric Fort on Cairngryfe Hill, near Lanark”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 75, 213-218.

- Childe, V. G. and C. D. Forde (1932): “Excavations in Two Iron Age Forts at Earn’s Heugh, near Coldingham”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 66, 152-183.

- Christison, D. (1887): “The Prehistoric Forts of Peeblesshire”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 21, 13-82.

- Christison, D. (1898): Early Fortifications in Scotland: motes, camps and forts, Edinburgh-London.

- Christison, D. (1900): “The Forts, ‘Camps’, and Other Field-Works of Perth, Forfar and Kincardine”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 34, 43-120.

- Christison, D. (1901): “Excavation Undertaken by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland of Earthworks Adjoining the ‘Roman road’ Between Ardoch and Dupplin, Perthshire”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 35, 15-43.

- Christison, D. and J. Anderson (1899): “On the Recently Excavated Fort on Castle Law, Abernethy, Perthshire with Notes on the Finds”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 33, 13-33.

- Christison, D. and J. Anderson (1905): “Report on the Society’s Excavations on the Poltalloch Estate, Argyll in 1904-5 with Relics Described”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 39, 259-322.

- Christison, D., J. Barbour and J. Anderson (1899): “Accounts of the Excavation of the Camps and Earthworks at Birrenswark Hill in Annandale, Undertaken by the Society in 1898”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 33, 198-249.

- Close-Brooks, J. (1983): “Dr Bersu’s Excavations at Traprain Law, 1947”, in: O’Connor & Clarke, dir. 1983, 206-223.

- Coles, F. R. (1891): “The Motes, Forts and Doons of the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright (part I)”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 25, 352-396.

- Cook, M. and McLaren, D. (2020): ‘Castle Law, Abernethy’, in Anon. Hillforts of the Tay, 46-53. Perth.

- Cook, M. (2010): ‘New light on oblong forts: excavations at Dunnideer, Aberdeenshire’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 140, 79-91.

- Cooney, G., J. Coles, M. Ryan, S. Sievers and K. Becker, dir. (2009): Relics of Old Decency: Archaeological Studies in Later Prehistory. Festschrift in Honour of Barry Raftery, Dublin.

- Cunliffe, B. W. (1988): Greeks, Romans & barbarians: spheres of interaction, London.

- Curle, A. O. (1905): “Description of the Fortifications on Ruberslaw, Roxburghshire, and Notices of Roman Remains Found There”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 39, 219-232.

- Curle, A. O. (1907): “Notes of Excavations on Ruberslaw, Roxburghshire, Supplementary to the Description of the Fortifications Thereon”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 41, 451-453.

- Curle, A. O. (1910): “Notice of Some Excavation on the Fort Occupying the Summit of Bonchester Hill, Parish of Hobkirk, Roxburghshire”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 44, 225-236.

- Curle, A. O. (1914): “Report on the Excavation in September 1913, of a Vitrified Fort at Rockcliffe, Dalbeattie, Known as the Mote of Mark”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 48, 125-168.

- Curle, A. O. (1923): The Treasure of Traprain: a Scottish Hoard of Roman Silver Plate, Glasgow.

- Dunwell, A. J. and I. Ralston (2008): Archaeology and Early History of Angus, Stroud.

- Dunwell, A. J. and R. Strachan, dir. (2007): Excavations at Brown Caterthun and White Caterthun Hillforts, Angus 1995-1997, Perth.

- Feachem, R. W. (1956): “The Fortifications on Traprain Law”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 89, 284-290.

- Feachem, R. W. (1963): A guide to prehistoric Scotland, London.

- Feachem, R. W. (1966): “The Hill-Forts of Northern Britain”, in: Rivet, dir. 1966, 59-87.

- Feachem, R. W. (1971): “Unfinished Hill-Forts”, in: Hill & Jesson, dir. 1971, 19-39.

- Frodsham, P., P. Topping and D. Cowley, dir. (1999): “We were always chasing time”. Papers presented to Keith Blood, Northern Archaeology Special edition 17/18.

- Graham, A. (1981): “In piam veterum memoriam”, in: Bell, dir. 1999, 212-226.

- Halliday, S. (2007): “Chapter 6: the Later Prehistoric Landscape”, in: RCAHMS 2007, 79-114.

- Halliday, S. and I. Ralston (2009): “How many hillforts are there in Scotland?”, in: Cooney et al., dir. 2009, 455-467.

- Hanson, W. S., dir. (2009): The army and frontiers of the Rome. Papers offered to David Breeze on the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday, Portsmouth, Rhode Island.

- Harding, D. W., dir. (1976): Hillforts: later prehistoric earthworks in Britain and Ireland, London.

- Harding, D. W., dir. (2004): The Iron Age in Northern Britain: Celts and Romans, Natives and Invaders, Abingdon.

- Haselgrove, C. C. (2009): The Traprain Law environs project: fieldwork and excavations 2000-2004, Edinburgh.

- Hill, D. and M. Jesson, dir. (1971): The Iron Age and its Hill-Forts; Papers Presented to Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Southampton.

- Hunter, F. J. (2009): “Traprain Law and the Roman world”, in: Hanson, dir. 2009, 225-240.

- Jobey, G. (1976): “Traprain Law: a summary”, in: Harding, dir. 1976, 192-204.

- Jobey, G. (1978): “Burnswark Hill, Dumfriesshire”, Trans Dumfriesshire Galloway Natur. Hist. Antiq. Soc., 3 ser 53, 57-104.

- Keppie, L. J. F. (2009): “Burnswark Hill: native space and Roman invaders”, in: Hanson, dir. 2009, 242-253.

- Laing, L. and D. Longley (2006): The Mote of Mark: a Dark Age Hillfort in South-West Scotland, Oxford.

- Lane, A. and E. Campbell (2000): Dunadd. An Early Dalriadic Capital, Oxford.

- Lock, G. (2019): ‘The Atlas: an introduction’, in : Lock & Ralston 2019, 3-8.

- Lock, G. and Ralston, I. (2017): Atlas of Hillforts of Britain and Ireland, [online] https://hillforts.arch.ox.ac.uk/

- Lock, G. and Ralston, I. (2022): Atlas of the Hillforts of Britain and Ireland, Edinburgh.

- Lock, G. and Ralston, I., eds (2019): Hillforts: Britain, Ireland and the nearer continent. Papers from the Atlas of hillforts of Britain and Ireland Conference, June 2017, Oxford.

- Lynch, M., M. Spearman and G. Stell, dir. (1988): The Scottish Medieval Town, Edinburgh.

- Megaw, J. V. S. and D. D. A. Simpson, dir. (1979): Introduction to British Prehistory, Leicester.

- Mercer, R. (2018): Native and Roman on the Northern Frontier, Edinburgh.

- Noble, G., O’Driscoll, J., MacIver, C. Masson-MacLean, E. and Sveinbjarnarson, I. (2020): ‘New dates for enclosed sites in north-east Scotland: results of excavations by the Northern Picts project’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 149, 165- 196.

- O’Connor, A. and D. V. Clarke, dir. (1983): From the Stone Age to the ‘Forty-Five’: Studies Presented to R B K Stevenson, Edinburgh.

- O’Driscoll, J. and Noble, G. (2020): ‘Survey and excavation at an Iron Age enclosure complex on Turin Hill and environs’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 149, 83-114.

- O’Grady, O and Fitzpatrick, J. (2018): ‘East Lomond Hillfort – Connecting Communities to the Ancient Landscape: Excavation’, Discovery & Excavation in Scotland, new ser,, 18, 95, Wiltshire.

- Ordnance Survey (1962): Map of Southern Britain in the Iron Age, Chessington.

- Owen, O. A. (1992): “Eildon Hill North”, in: Rideout et al. 1992, 21-71.

- Piggott, C. M. (1948): “The excavations at Hownam Rings, Roxburghshire 1948”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 82, 193-225.

- Piggott, C. M. (1949): “The Iron Age Settlement at Hayhope Knowe, Roxburghshire. Excavations 1949”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 83, 45-67.

- Piggott, C. M. (1950): “Excavations at Bonchester Hill, 1950”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 84, 113-137.

- Piggott, S. (1966): “A Scheme for the Scottish Iron Age”, in: Rivet 1966, 1-15.

- Piggott, S. and C. M. Piggott (1952): “Excavations at Castle Law, Glencorse, and at Craig’s Quarry, Dirleton, 1948-9”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 86, 191-4.

- Ravilious, K. (2021): ‘Land of the Picts’, Archaeology (Archaeological Institute of America), 441, [online] https://www.archaeology.org/issues/441-2109/letter-from/9932-scotland-picts

- RCAHMS (= The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions of Scotland) (1908): First Report and Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in the County of Berwick, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1912): Fourth Report and Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in Galloway, I, County of Wigtown, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1914): Fifth Report and Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in Galloway, II, County of the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1915): Sixth Report and Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in the County of Berwick, Revised Edition, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1924): Eighth Report with Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in the County of East Lothian, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1928): Ninth Report with Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in the Outer Hebrides, Skye and the Small Isles, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1956): An inventory of the ancient and historical monuments of Roxburghshire, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1957): An inventory of the ancient and historical monuments of Selkirkshire, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1967): Peeblesshire: an inventory of the ancient monuments, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1971): Argyll: An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments, Volume 1: Kintyre, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1975): Argyll: An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments, Volume 2: Lorn, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1978): Lanarkshire: An Inventory of the Prehistoric and Roman Monuments, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1980): Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments, Volume 3: Mull, Tiree, Coll and Northern Argyll (excluding the early medieval and later monuments of Iona), Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1984): Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments, Volume 5: Islay, Jura, Colonsay and Oronsay, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1988): Argyll: an Inventory of the Monuments, Volume 6: Mid-Argyll and Cowal, prehistoric and early historic monuments, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1990): North-east Perth: an archaeological landscape, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1994): South-east Perth: an archaeological landscape, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (1997): Eastern Dumfriesshire: an archaeological landscape, Edinburgh.

- RCAHMS (2007): In the shadow of Bennachie: a field archaeology of Donside, Aberdeenshire, Edinburgh.

- Ralston, I. (1979): “The Iron Age: northern Britain”, in: Megaw & Simpson, dir. 1979, 446-501.

- Ralston, I. (2004): The Hill-Forts of Pictland since “The Problem of the Picts”, Rosemarkie.

- Ralston, I. (2006): Celtic fortifications, Stroud.

- Ralston, I. (2007): “The Caterthuns and the hillforts of North-East Scotland”, in: Dunwell & Strachan, dir. 2007, 8-12.

- Ralston, I. (2009): “Gordon Childe and Scottish archaeology: the Edinburgh Years 1927-1946”, European Journal of Archaeology, 12 (1-3), 47-90.

- Reid, J. H. and Nicholson, A. (2019): ‘Burnswark Hill: the opening shot of the Antonine reconquest of Scotland?’, Journal of Roman Archaeology, 32, 459-477.

- Rideout, J. S., O. A. Owen and E. Halpin (1992): Hillforts of southern Scotland, Edinburgh.

- Ritchie, J. N. G. (2002): “James Curle (1862-1944) and Alexander Ormiston Curle (1866-1955): pillars of the establishment”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 132, 19-41.

- Rivet, A. L. F., dir. (1966): The Iron Age in northern Britain, Edinburgh.

- Rivet, A. L. F. and C. Smith (1979): The place-names of Roman Britain, London.

- SERF n.d. (= University of Glasgow Strathearn Environs and Royal Forteviot Project) ‘Castle Law, Forgandenny’, [online] https://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/humanities/research/archaeologyresearch/currentresearch/serf/inthewiderlandscape/fortsaroundforteviot/castlelawforgandenny/

- Simpson, J. Y. (1866): “On Ancient Scupturings of Cups and Concentric Rings”, being an Appendix to Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 6, 1-147.

- Simpson, W. D. (1920): “The Hill fort on the Barmkin of Echt, Aberdeenshire”, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 54, 45-50.

- Wedderburn, L. M. M. (1973): Excavations at Greencairn, Cairnton of Balbegno, Fettercairn, Angus: a Preliminary Report, Dundee.

Footnotes

- cf. Halliday & Ralston 2009.

- e.g. Lynch et al. 1988; Harding 2004, 58-66.

- e.g. Simpson 1866, 44-47.

- Christison 1887.

- Christison 1898.

- Christison 1898, 114.

- Christison 1898, 386.

- Halliday & Ralston 2009, 458.

- Graham 1981, 216.

- e.g. Coles 1891.

- RCAHMS 1908; 1915.

- Christison & Anderson 1899.

- with Barbour and Anderson: Christison et al. 1899.

- Christison 1901.

- Christison & Anderson 1905.

- Graham 1981, 216.

- Curle 1914.

- Curle 1905; Curle 1907.

- Curle 1910.

- see Ritchie 2002 for Curle’s bibliography.

- Curle 1923.

- Childe 1935a, 206-8, 249-50.

- Childe 1935a, 274-275 Map IV.

- Ralston 2009, 73-75 footnote 39 and fig. 5.

- Piggott 1948.

- Piggott 1949.

- RCAHMS 1956, 18.

- Feachem 1956, 286-287.

- Effectively published as Feachem 1963.

- Feachem 1963, 103.

- Feachem 1966, esp. 77-82.

- Ordnance Survey 1962, 13.

- Childe 1935a.

- Feachem 1966 fig. 13 cf. Ralston 1979 fig. 7-49.

- Halliday & Ralston 2009 fig. 5, reproduced here as fig. 2.

- Feachem 1966 fig. 13.

- Childe 1935a.

- RCAHMS 1980, 18.

- Burgess 1999; Burgess & Church 1997.

- RCAHMS 2007; Dunwell & Ralston 2008.

- RCAHMS 1994, 12-13, 48-59; Ralston 2007; Halliday 2007.

- Ralston 2007; Halliday 2007, 96-105.

- Feachem 1971.

- Ralston 2006.

- Rivet & Smith 1979, 289.

- Dunwell & Strachan 2007.

- Dunwell & Strachan 2007, 71.

- Dunwell & Strachan 2007.

- Feachem 1966, 66-68.

- Childe 1935a, 193-7, 236-237.

- Christison & Anderson 1899.

- Childe 1935a, 193-195.

- Hunter 2009.

- cf. Cunliffe 1988, 167.

- Keppie 2009.

- e.g. Harding 2004.

- e.g. Lynch et al. 1988.

- Piggott 1966.

- Armit 1997, 50-4; Haselgrove 2009, 225-231.

- Ralston 2004, Ralston 2006.