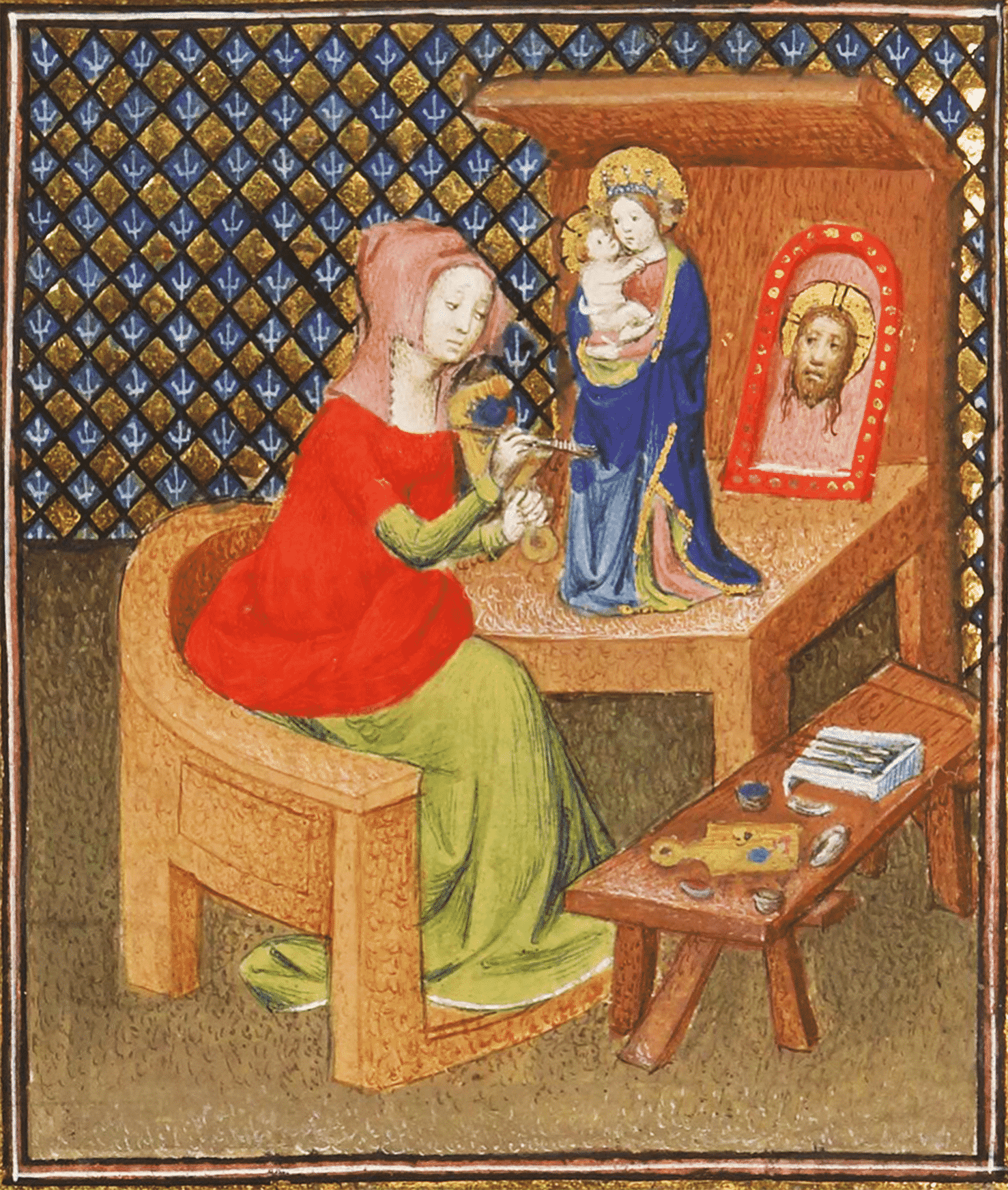

“Remove from a statue its polychromy, and it loses something of its beauty:

remove the light that makes it shine, and it loses all aesthetic value.”

De Bruyne 1946, 213, paraphrasing a sermon by St Bonaventure in honour of the saints.

During the last two centuries of the Middle Ages, between about 1330 and 1530, English sculptors exploited the alabaster deposits in the Midlands on a large scale to create funerary monuments with recumbents, altarpieces and small devotional reliefs (figs. 2, 3). These works were produced both for the English domestic market and for export to other European countries. During the Anglican Reformation from 1532 onwards, and later during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651), almost all the religious scenes from altarpieces and devotional images were destroyed in England. Despite these massive losses, more than 2,400 alabasters from the quarries in Derbyshire and Staffordshire still survive, mainly in various European countries, but also in American museum collections and as far away as Australia.1

Immediately recognisable, English alabasters show a remarkable formal and visual homogeneity, almost as if they were produced by the same workshop. The majority of the panels have similar dimensions (approximately 40/50 x 25/30 cm), highly standardised iconographic compositions and colour layout as well as a particular stylisation of the figures, characterised primarily by their elongated proportions.2

Because of the close historical links with England, a large quantity of these alabasters have been preserved in the south-west of France and in particular in and around Bordeaux. More than a hundred have been inventoried in the region.3 Initially, their number was certainly much higher, as illustrated by the fourteenth-century Passion altarpiece, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London,4 the Weighing of the Souls panel now in the Louvre,5 and the Compans Altarpiece, recently sold by Sotheby’s – all originating from Bordeaux or its region.6

Notes

- In his book published in 2003, Francis Cheetham could list more than 2,400 panels. According to Zuleika Murat, there are even more than 3,000 known panels. See eadem 2019, 8, note 38.

- Careful examination of the panels sometimes makes it possible to reconstruct part of the ‘oeuvre’ of a particular sculptor, such as the ‘Master of the Lydiate Altarpiece’ (De Beer 2018, 196 sq.). However, the general impression of stylistic homogeneity clearly prevails, as is demonstrated by the difficulty of dating the so-called Nottingham alabasters.

- The inventory and study of the alabasters was carried out by Le Noan-Vizioz 1957. The corpus was extended to the south-west of France in Gorguet’s master’s thesis written in 1984.

- Inv. no. A.48 – 52-1946. For the (probable) Bordeaux origin of the altarpiece, see first Hildburgh 1925, 307.

- Inv. no. RF 1959 ; the first known owner of the panel, François-Vatar Jouannet, was librarian of the city of Bordeaux (Bresc-Bautier 2006, 59).

- The altarpiece was sold in 2016; see https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2016/treasures-l16303/lot.2.html (last accessed on 11 February 2022). According to the information provided by the auction house ibid., “it is most probable that the original home of the Compans Retable was in a church in the area around Bordeaux, given that it was here that Mgr Alexandre Compans acquired it circa 1905.”