Context and dating

The study of a first panel, preserved in Libourne (Gironde), allows us to illustrate the approach used and the type of observations that can be made, as well as the reconstruction of its polychromy.

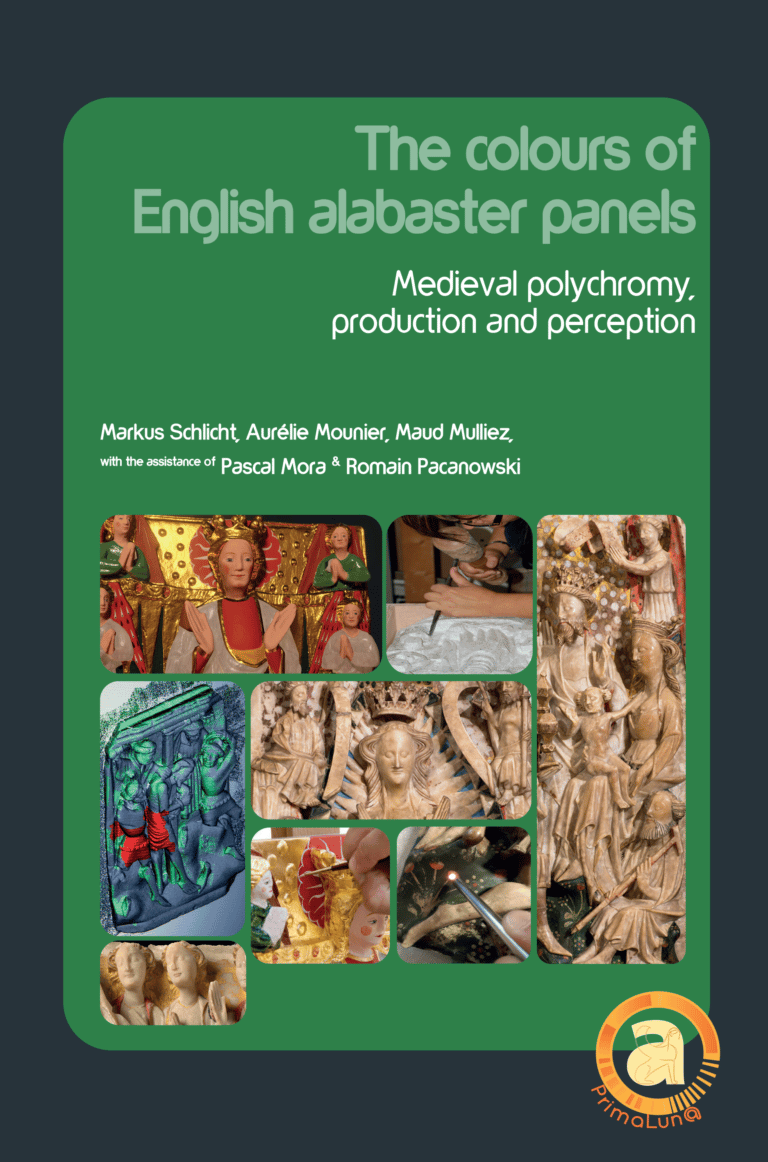

The panel illustrating St Peter greeting the Elect to Paradise is kept in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Libourne (fig. 8).1 Placed in front of the open door of the Celestial Jerusalem, the first apostle welcomes three Elect, their hands clasped in prayer. Behind them rises the battlemented wall of the heavenly city. The archangel Michael, who stands before this wall, invites the Elect to approach the entrance. Behind the battlements appear two angels, one playing a psaltery, the other a guiterne or small lute. The tablette is part of a set of three panels illustrating scenes of a Last Judgement, each measuring 42 x 27 cm.2 This small set comes from the private chapel of what was, in the 18th century, the house of the Bulle family, one of the most influential in Libourne. Unfortunately, we do not know since when these panels have been in this house nor who commissioned them.3

The panel depicting the Elect entering Paradise is relatively well preserved, as indicated by the large areas of medieval polychromy, under which the alabaster’s epidermis is still intact. However, there are several damages and losses. The head of the angel in the upper right-hand corner of the panel and the two pinnacles above the door have been destroyed; they have since been reconstructed in plaster. The keys of St Peter are missing, and the tips of the angels’ wings on the wall are chipped. All of this damage and the subsequent repairs predate the beginning of the 20th century, as they already appear in a photograph by Jean-Auguste Brutails.4

The dating of the Libourne panel, like that of the vast majority of English alabasters, is difficult to establish. The chronological grids that are usually applied to them do not allow us to specify this beyond a very vague fifteenth century. Considering other chronological clues, such as the very smooth and unbroken folds of Peter’s draperies, the formal treatment of the architecture of the doorway and that of the figures’ hairstyles, we would tend to place the alabaster in the first half of the fifteenth century, perhaps as early as its first quarter.5

The medieval polychromy of the panel, consisting of large areas of bright red, gold, pink and dark green, is fairly well preserved. It has recently been restored, which has made it possible to consolidate the pictorial layers, which were powdery in places, and to eliminate the greyish salt deposits that were partially masking them.6 The freshness of the colours has thus been partially recovered and their reading has been significantly improved. Nevertheless, the polychromy shows many gaps and alterations. The identification of the remaining chromatic data (colours and pigments) is therefore an essential step in attempting to restore the original appearance of the panel.

The polychromy of the panel

The figures on the panel, whether clothed (Peter, the angels) or naked (the Elect), almost everywhere show the colour of alabaster. The Elect therefore do not have a pink complexion, but an entirely white skin. Their hair and certain facial features, the painting of which is now usually lost, were the only coloured elements. Their hair is of various colours: that of the left-hand figure is painted in yellow ochre, that of the middle figure in red ochre and that of the last figure shows a pale yellow tint, the dye of which, probably of an organic nature, could not be determined (fig. 9 and 10).

St Peter also has a white complexion and bright red lips; the paint on the nostrils, eyes and eyebrows – still clearly visible in the case of the figures on the panel of the Resurrection of the Dead in Libourne (fig. 11) – has disappeared here. The apostle’s tonsured hair and beard are gilded, as are the two fragmentary keys in his right hand. He is wearing a long robe with fitted sleeves and a cloak. The robe is white (alabaster) on the obverse side and was originally provided with a row of large golden buttons on the bust.7 The lining is painted bright red with cinnabar, traces of which remain on the collar. The coat also has a white obverse, while the lining is coloured with a strong azurite blue. All the hems of the dress and coat are highlighted with gold-leaf edging (fig. 9).

St Peter stands before the gate of Paradise, whose late gothic architectural frame is entirely gilded. The two main pinnacles above his head are each decorated with two pairs of green lines (copper resinate) disposed in a chevron pattern, painted directly onto the gilding (fig. 9). These pinnacles end in two gargoyles at the bottom. Their monstrous heads are white (alabaster); their mouths and nostrils are painted bright red, their large eyes show a black iris (very fragmentary) on a gilded background (of which only the undercoat remains). The door to Paradise opens onto a bright red (cinnabar) monochrome ‘space’ strewn with white ‘suns’ (lead white). This door is surmounted by three shallow barrel vaults, uniformly painted with red lead, which produces a bright orange colour.8

The wall of the Celestial Jerusalem, which adjoins the door to the right, is made of pink large-scale masonry (a mixture of cinnabar and, probably, lead white), the joints being drawn in white (lead white). It rests on a moulded plinth decorated with gesso nodules (now lost), all of which have been gilded with gold-leaf. The pink wall is topped by a corbelled parapet. The courses of the parapet, left in white (alabaster), are surrounded by a cinnabar red line; the battlements are painted with the same bright red. The merlons are white (alabaster) and end in a semi-cylindrical moulding adorned with gold-leaf.

St Michael stands before the pink wall. Like the other figures, his complexion is entirely white and, like that of St Peter, his hair is golden. With the exception of the cinnabar red lips, his facial features (eyes, eyebrows, nostrils), which were once painted, have now disappeared. He is dressed in an entirely white alb with a raised collar. The lower part of the alb is decorated with a wide gold band overlaid with black diamond-shaped lines. The upright collar – probably an amice – has gold foil edges; the lining is painted cinnabar red. The wings of the archangel show a complex superimposition of colours, the stratification of which could not be determined with certainty due to a lack of sampling. According to our observations, they were first gilded – the leaves were placed on an orange mixtion (oil and red lead) –, then painted in translucent green (copper resinate and oil); tear-shaped feathers were then placed on this green glaze. Green tears with white spots, arranged fairly freely in registers, alternate with rows of red tears, also adorned with white spots (fig. 9 and 12).

The angel playing the guiterne has a white (alabaster) skin, golden hair and a white alb with a raised collar surrounded by golden borders. His red wings, painted with cinnabar, are decorated with white tear-shaped feathers, each with a black dot (carbon black; fig. 9). His musical instrument is gilded on the front, while the sides are painted with an unidentified organic yellow; the strings have been drawn in red. The angel with the psaltery is dressed in the same alb as his neighbour, and his wings show the same white tears with black spots on a cinnabar red backdrop. The frame of the psaltery is golden, the triangular area it encloses being painted pale yellow; the strings are drawn in black.

The backgrounds of the panel are divided into two parts with different colouring. The Elect and St Peter stand on a monochrome green meadow (probably copper resinate) with stylised flowers consisting of six lead white dots around a cinnabar red dot (fig. 9). Behind the door of Paradise and the angelic musicians, the backgrounds are gilded with gold-leaf and strewn with gesso nodules, similarly gilded.

Observations and interpretation

Taken as a whole, the polychromy of the panel consists of a relatively limited range of colours, generated by as many different pigments. Apart from the alabaster, which is often apparent, and the gilding, it is essentially made up of bright red (pigment used: cinnabar), orange (lead red), deep green (verdigris and/or copper resinate) and intense blue (azurite). In addition to these pigments, which are used in large quantities, other colouring materials are employed much more sparingly. This is the case with the red showing purple shades (red ochre) that colours the hair of the central Elect and the eyebrows of the two monsters at the gate of Paradise.9 The hair of the last Elect and the triangular area of the psaltery were painted with a ‘citrine’ colour, generated from pale yellow organic pigments.10 Yellow ochre was used to colour the hair of the first Elect. White paint – lead white – was used for the ‘suns’ on the doorway to Paradise, as well as for the flowers on the green background and the tear-shaped feathers (fig. 9). Black is almost completely absent: only a few lines on the trimmings of St Michael’s alb were drawn with carbon black. Initially, the pupils (now erased) of the figures and the small gargoyles of the gate of Paradise were probably depicted with this same black.11

The pigments used were almost always applied pure. The main exception to this rule is the pink or ‘incarnal’ tone covering the wall of the heavenly Jerusalem.12 It was obtained by mixing cinnabar and, probably, lead white.13 If pigment mixtures were therefore part of the painting practices of the Libourne panel painter, it is striking to note that he only rarely had recourse to them.

Some pigment mixtures, as revealed by physico-chemical analyses, were not so much used to generate additional colours as to reduce the drying time of the paints. The binder used on the alabasters to fix the pigments was in fact an oil (of the linseed or walnut oil type). As the drying time of this binder was very long – from several days to several weeks – the addition of a siccative did not delay the completion of the work too much. The addition of small amounts of lead, in the form of red lead (for red surfaces or gilding mixtions) or lead white (for blue surfaces, for example), considerably shortened the drying time.

The limited range of colours was sometimes extended by the superimposition of several layers of paint. This is the case for the wings of St Michael (fig. 12). The green copper resinate is superimposed on gold-leaf. Thanks to this process and the transparency of the resinate, this green appears more yellow, but also more luminous, than when it is applied directly to the alabaster. The same applies to the small green chevron-shaped lines on the golden pinnacles of the gate to Paradise (fig. 9).

These multi-layer overlays, which play on transparency effects, are however limited to these two examples. As a rule, the colours are opaque – despite the fact that they are applied directly to the support, without the intermediary of underlays. Only the azurite blue of Peter’s mantle was applied on a blackish underlayer (fig. 9).14

The colouring of the alabaster is not exclusively based on the use of pigments. In fact, the main colours of the panel have not yet been addressed: white and golden yellow.

Despite the many painted surfaces, white – alabaster white – remains the dominant colour of the panel. When exposed to the air for a long time and under the effect of environmental agents, alabaster takes on a greyish, yellowish or beige patina. However, freshly quarried alabaster from England is distinguished by its bright white colour, as recent breakages confirm. Moreover, the surfaces often appear slightly rough and ‘pitted’ today, whereas they were originally polished, as shown, among others, by those that were until recently protected by a layer of paint (fig. 13).

It should be remembered that alabaster can be naturally coloured in different shades, such as yellowish, light grey, green, red-brown and even black.15Unlike some 20th century sculptors who used coloured English alabaster such as Cumberland alabaster (pink or honey-coloured),16 their medieval predecessors used only Derbyshire and Staffordshire alabaster, which is characterised by its pure milky white.17 The immaculate, brilliant white colour was obviously a decisive criterion for the choice of this material.18 Albert the Great echoes this medieval admiration for the colour of alabaster: “But among marbles, the white [kind] called alabaster is undoubtedly composed of a great deal of transparent [material…]; and the result is a most noble, sparkling colour in it.”19 On English panels, the whiteness of alabaster thus takes the place of colour. It replaces the actual white paint, which is only used when white is applied to a surface that has already been painted with another colour, as in the case of the ‘suns’ that dot the red space behind the door to Paradise.20

After white, the most used colour is gold. The precious metal colours the most diverse elements, from the frame of the door to Paradise to the hair of the angels and St Peter, not forgetting the gold edging on the clothes and the backgrounds adorned with gesso nodules. It may seem inappropriate to include a metal in the inventory of colours of the Libourne panel. However, as Michel Pastoureau has pointed out, the colour yellow, which was not much appreciated by the medieval viewer, gradually disappeared from painted works and dyed fabrics at the end of the Middle Ages; it was replaced more and more systematically by gold, which was charged with positive connotations.21 Many medieval authors, such as the herald Sicille (c. 1435), considered gold to be a colour – in this case yellow – in the same way as azure, red or green.22

Most often, objects or even entities such as the landscapes of the backdrops or the sky are painted in a single colour. These monochrome colours have not been chromatically ‘modelled’. For example, the space to which the door to Paradise opens is indicated by a uniform red surface. As far as the strong alteration of the pigments makes it possible to judge, the same was true of the green backdrops. It is the relief of the support that introduces nuances of colour, certain zones being exposed to light, others on the contrary plunged into shadow.

As each object has a specific, highly saturated colour, the panel as a whole is characterised by a multitude of brightly coloured chromatic poles. As a rule, two colours that are adjacent to each other have very different colour values, such as white and red or gold and green. No attempt has been made to smooth the transition from one colour to another, such as a gradient. On the contrary: the precise delineation of coloured surfaces and objects and their clear separation from those around them is a constant concern for the painters. The colouring of St Peter’s clothes illustrates this. Without the colouring, it is sometimes difficult to decide whether a particular piece of cloth belongs to the cloak or to the tunic of the saint. In order to disambiguate the composition of the draperies, the painter encircles all the hems of the cloak and robe with golden borders. These borders create sharp, clear-cut boundaries that the eye immediately grasps. The same hemlines also create ‘visual barriers’ between the robe and the skin of the saint, both of which are white (alabaster; fig. 14). The exclusive use of pure, plain colours, their direct juxtaposition and the absence of modelling – even though the modulation of the colours occurs ‘naturally’ through the relief of the sculpture – give the panel a highly artificial appearance. Objects are repeatedly not given the colours that are naturally theirs. For example, skin tones are white rather than flesh-coloured, and hair frequently has the metallic lustre of gold rather than a realistic colour approaching blond. The reduction of certain natural elements to simple geometric forms reinforces the abstract dimension of the image. For example, the infinite natural diversity of plant species is reduced to a single one, in this case the ‘daisies’ on the green background, and the morphological complexity of actual flowers is simplified to the extreme (a red dot surrounded by six white dots; fig. 9 and 14).23 The painter thus deliberately turns away from mimesis, i.e. the imitation of nature. On the contrary, the painting confirms and accentuates the non-realistic tendencies of the sculptor’s work, which are manifested, among other things, by the marked elongation of the proportions of the figures, by the simplification of anatomical details (or even by their pure and simple suppression, as in the case of the ears) or by the way in which the various architectural elements are assembled, which is not aimed at creating a coherent three-dimensional space.

Notes

- Inv. no. 02.1.45.

- Curiously, the Judgement itself is not represented, or at least has not been preserved. Francis Cheetham has been able to identify only two panels depicting this subject, one in a British private collection and the other sold by Sotheby’s in 1984. Both panels feature an enthroned Christ, two angels, the Virgin and St John kneeling, and naked men emerging from their graves. See Cheetham, 2003, 145.

- The house and its chapel have now disappeared. In the 18th century, two members of the Bulle family were subdelegates of the Intendant, i.e. representatives of the king in Libourne (“Séance du 18 mars 1984”, Revue historique et archéologique du Libournais, 1984, 54, 59-60). Léonard Bulle, who died in 1773, was the first president of the présidial of Libourne, subdelegate of the Intendant, lieutenant general of the seneschal and, from 1747 to 1749, mayor of Libourne. See Ardouin 1923.

- The date of Jean-Auguste Brutails’ photograph is not known. The eminent scholar arrived in the Gironde département in 1889 and took a large number of photographs of the region’s cultural heritage, many of which were intended for publication in his book Les vielles églises de la Gironde published in 1912. We would like to thank Julien Baudry for providing us with this information.

- According to traditional chronological classifications, the presence of a battlemented canopy over the scene, carved from the same block as the scene, is considered characteristic of the period between 1380 and 1420 approximately; the Libourne panel, devoid of these battlements, should thus be dated, according to these criteria, after 1420. The hairstyles of the male figures, typical of the Anglo-Burgundian fashion of the years 1410 to 1440, also allow a slightly earlier date. Peter’s flowing draperies, with their thin folds and harmoniously rounded curves – which do not feature any drawn folds, edges or breaks – are still very close to the stylistic conventions in vogue in the 14th century. The stylistic archaism that is often postulated for English alabasters has not yet been fully demonstrated (nor disproved) – which is why we do not consider it necessary to rejuvenate this dating.

- The restoration was carried out in January 2019 by Tiziana Mazzoni.

- There are clearly visible remains of the upper golden button. The size of this button, as well as the location and shape of the other two, can easily be deduced from the smooth, circular marks that remain on the chest, due to the fact that here the alabaster surfaces have long been protected by the gilding. The areas around the buttons, in contrast, are rougher. In addition, comparisons with alabaster panels showing a better preserved polychromy, such as those from Rabastens, now in the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse, give a fairly accurate idea of the initial layout: three superimposed gilded buttons, linked together by a red line (which corresponds to the lining, as the dress is slit on the bust).

- Two patches of cinnabar red appear on these barrel vaults; given their asymmetrical and irregular location and shape, they are probably accidental.

- As strongly suggested by the painting practices observed on other English alabaster panels, the eyelids of the eyes and the openings of the nose of the figures, now lost, were probably painted in red ochre, the latter maybe also with cinnabar red.

- The precise nature of the pigment could not be determined. For the name of this colour, we could refer to a passage in Sicille’s treatise on heraldry, which explains about yellow: “Ceste couleur est de trois genres. La premiere est jaune moyenne couleur, la seconde est plus clere, et est couleur citrine, que nous disons jaune palle, la tierce punicée, et traict sur le rouge, et est ce que nous disons jaune orenge.” [This colour is of three kinds. The first is yellow medium colour, the second is clearer, and is citrine colour, which we call pale yellow, the third punicate, and it has a red tinge, and it is what we call yellow orange.] (Sicille, ed. Cocheris 1860, 82).

- As far as we know, all the pupils of English alabasters have been painted in black.

- According to the herald Sicille (15th century), incarnal or incarnate was “une couleur moult belle et gaye. Elle approche fort du rouge, mais elle est ung peu plus chargée et traict fort sur le blanc”. [incarnal is a very beautiful and gay colour. It is very close to red, but a little more charged and has a strong white tinge”. (Sicille, ed. Cocheris 1860, 89) The author considers incarnal to be a colour in its own right, in the same way as white, red, green etc.

- Due to the lack of a suitable instrument, the white pigment in this panel has not been formally identified. However, it is the white dye usually used by alabaster painters, and it has been detected on other panels in the Aquitaine corpus.

- The pigment used for the undercoat has not been identified: indigo or carbon black?

- Lipińska, 2015, 17; the author goes on: “Historically, however, only light-coloured types were referred to as alabaster. The various types of alabaster also differ in the forms and colours of their veining and clouding.”

- Lipińska, 2019, 66-70.

- The alabaster of the Midlands is not always free of impurities (often orange-brown in colour), but the immaculate whiteness of the material clearly remains predominant.

- Some authors tend to think that the predilection for this material is explained by the more or less miraculous virtues that the Middle Ages attributed to alabaster. Thus, it was thought that this stone could slow down the corruption of corpses, preserve ointments or perfumes, or create friendship. The first of these supposed properties certainly had an influence on the widespread fashion for alabaster tombs, especially in England. However, alabaster does not seem to have been used in medieval England for the manufacture of ointment jars; unlike the Egyptian calcareous alabaster used in Antiquity, English gypsum alabaster is unsuitable for containing such substances. The miraculous properties mentioned in medieval treatises cannot therefore explain, at least not on their own, the popularity of this material in the late Middle Ages and beyond.

- Albert the Great trans. Wyckoff 1967, 44.

- Other examples are the small stylised white flowers on the green background of the panel, the white joints of the wall of Paradise or the white tears on the angels’ wings.

- Pastoureau 2012, 231-232.

- The herald Sicille states in his chapter “Comment se doibt porter le jaulne” [“How to wear the colour yellow”] : “Les roys, princes, chevaliers le portent en leurs heaulmes, harnoys et esperons dorez, qui est couleur jaulne. Aussi les femmes portent plusieurs anneaulx d’or qui représente le jaulne.” [“The kings, princes, knights wear it in their golden helmets, harnesses and spurs, which is yellow in colour. Also the women wear several rings of gold that represents the yellow colour.”] See Sicille, ed. Cocheris 1860, 109.

- It would probably be wrong to consider this motif as an expression of ‘naïve’ or ‘popular’ painting. It can also be found in court art, for example in the backdrops of the enamelled scenes decorating the base of the Virgin and Child donated by Joan of Evreux to Saint Denis, and dated 1339 (Paris, Musée du Louvre). According to Pitman 1954, 217, the ‘floral dotted foreground’ also appears in the illuminations of Mary Tudor’s Psalter (14th century) and the Duke of Bedford’s Book of Hours (early 15th century), both in the British Library. These examples had already been cited by Prior 1913, 23.