Foreward

In the more recent of Olivier Buchsenschutz’ two overviews of Iron Age archaeology1 –both elegantly written and attractively presented essays on a complex period of prehistory– we read of the third and second century ‘Plastic’ style:

Les motifs se développent largement dans les trois dimensions de l’espace, la complexité des symétries donne une impression de déséquilibre ou de mouvement rotatif, la multiplicité des détails est exubérante, baroque.2

The present paper is a contribution to the study of what is certainly one of the most intriguing and by the same token most perplexing of those styles first defined by Paul Jacobsthal3.

Introduction: description and context (JA, EM)

Research on the eastern borders of the Celtic world, and particularly on the La Tène –or presumed La Tène– finds in Thrace, is still largely dependent on the syntheses carried out by Zenon Wożniak and Mieczysłav Domaradzki in the 1970s and 1980s4. Over the past twenty years, significant discoveries and acquisitions by Bulgarian archaeologists and museums provide a new basis which justifies the reopening of this issue5.

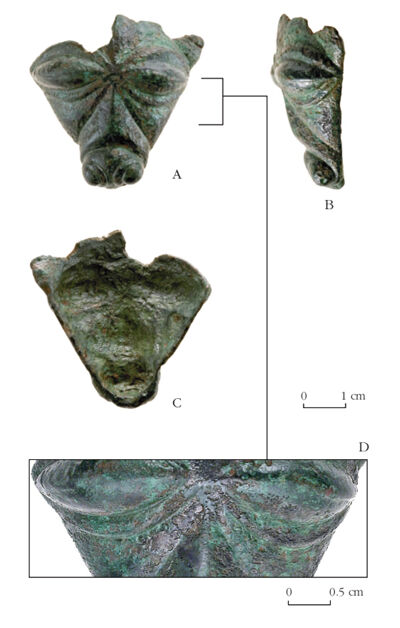

The Varna Museum of Archaeology, located on the Bulgarian Black Sea coast, stands out due to the quantity as well as the quality of its Iron Age collection6. It includes more than one hundred artefacts, mostly unpublished, discovered in north eastern Bulgaria since the end of 1980s. Among the most remarkable pieces preserved in the Museum is a bronze zoomorphic head7. While this object has already been the subject of a summary publication, its stylistic qualities and the need to determine its chronological and functional aspects have given rise to the current study. The object was discovered in the 1990s and unfortunately is without context. All that is known is that it comes from north-eastern Bulgaria (fig. 1).

Unprovenanced bronze head from north-eastern Bulgaria. L 42 mm, W 43 mm

(photo J. Anastassov).

![Graphic reconstruction of the bronze head (drawing Eva Gutscher, Laboratory of prehistoric archaeology and anthropology [F. A. Forel], Geneva University).](https://nakala.fr/iiif/10.34847/nkl.afaec2p0/full/400,/0/default.jpg)

(drawing Eva Gutscher, Laboratory of prehistoric

archaeology and anthropology

[F. A. Forel], Geneva University).

The head is a fragment of a bronze mount in all probability cast by the cire perdue method; its original form cannot be restored (fig. 2-3). Triangular in shape and with a hollow cross-section (length 42 mm and width 43 mm) the preserved frontal aspect is built up from a number of protuberant elements –a key aspect of Jacobsthal’s ‘Plastic’ style. Basically, the face consists of two almond-shaped eyes and a muzzle of two spirals. Typically, the face has an ambiguous aspect, though the muzzle and what may be a fragment of a horn on the left side suggests animal rather than human. A series of stamped circles is partially preserved under the eyes. The patina, relatively well preserved, indicates that the bronze had been preserved in an enclosed atmosphere prior to its discovery.

In its original position, the concave side would have been hidden, its flattened border suggesting that it was applied to a smooth and slightly curved surface.

The Varna mount: stylistic considerations (JVSM, MRM)

As mentioned at the outset, the Varna mount on stylistic grounds –and we have no other feature to rely on– is typical of the Plastic style which Felix Müller has recently described as ‘entire compositions, hitherto drawn on the surface, were mounted on the body of the ring as a three-dimensional decoration’8. There are in fact in this style very few exceptions to what would appear –at least at a first glance– to be largely abstract forms. There is, however, one other aspect of Jacobsthal’s ‘Plastic’ style, which, though not represented by many examples, is scattered across the whole known distribution of La Tène culture and indeed beyond, from Scandinavia to the Balkans –as our Varna mount gives evidence.

This group of stylised representations, dated in general to La Tène B2-C1, we have dubbed the ‘(Walt) Disney style’ only partly in jest, as in the case of Jacobsthal and the prior ‘Cheshire (cat) style’9. No other group of early Celtic art exhibits such a variety of imagery or has inspired such varied interpretations. The characteristic features of this group are, unusual for the period, unambiguous faces, both animal and human and sometimes, ambiguously, both. These are constructed of a number of curvilinear geometric forms in the manner of the film cartoonist’s art10. One of the largest group of objects are the chariot fittings found in the tholos tomb of Mal Tepe, Mezek (Haskovo) first published by Bogdan Filow in 1937 followed by Jacobsthal and recently reconsidered11 (fig. 4a). Since then there has been much discussion of the sequence of the tomb’s use and re-use –not assisted by the fact that the site was considerably disturbed by its initial discoverers– as well as what might be the immediate source of the indisputably foreign element represented by the La Tène fittings. The most recent analysis suggests that these bronzes are the latest feature of the tomb and represent an isolated group of objects, possibly trophies, unrelated to the burials of a male and two females12. A date for the deposition of these fittings just before or just after the Celtic incursions culminating in the raid on Delphi in 279 BC, an event which has left little in the archaeological record, still seems most likely. As Jacobsthal has noted, the Mezek mounts may be compared with the Canosa helmet13 –Celtic objects in totally foreign contexts– and both are as likely to be trophies of the battle as to indicate the presence of foreign mercenaries.

National Archaeological Museum, Sofia

(photo Rosa Staneva).

Close to Mezek is the group of mounts whose provenance as Paris it is no longer necessary to doubt14 (fig. 4c). Most striking of these is the terret15 where the faces have been contorted in a manner which has caused us16 to follow Nancy Sandars17 and think of the hero of the Ulster hero tales, Cú Chulainn, and his ability to contort his face in battle. Laurent Olivier and Philippe Charlier18 present an alternative reading –that the contortions display features of the medical conditions known as the Parry-Romberg and Goldenhar syndromes and that as a whole our ‘Disney’ group does not simply represent a cartoonist-like process of abstraction but rather a more meaningful approach to representing the human and the inhuman condition.

More recently, a number of other finds in the Paris Basin, notably in the La Tène B2 cemetery of Roissy-en-France ‘La Fosse Cotheret’ (Val-d’Oise) extend the evidence for this stylistic sub-group. One of two chariot graves nicknamed ‘la Tombe des Bronzes’ –some twenty-five are decorated– includes an openwork mount comprising a series of ‘sea-horses’19 which in detail exhibit a stylised combed-back forelock recalling the Paris terret; there is also a linch-pin (fig. 4b) comparable in form to the pair from Mezek (fig. 4a) but with more than a hint of faces with staring eyes and a bulbous nose. Apart from chariot fittings, it is noticeable that the occurrence of ‘Disney’ faces is on objects of high status. These include the cauldron mounts of a deliberately destroyed bronze cauldron found in 1952 buried in a pit at Braa near Horsens in eastern Jutland20 (fig. 4d); this Danish find has been frequently compared with the mounts for a spouted flagon found by chance in 1941 on the edge of the large cemetery at Brno–Maloměřice mainly dated between La Tène B1-B2/C121 (fig. 4h). Perhaps the oddest find front the point of view of location is a gold finger-ring in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London allegedly discovered on Sardinia22 (fig. 4e). The Braa cauldron mounts comprise the heads of bulls (fig. 4d, left) while –amongst several examples of readily identifiable birds in the early Celtic zoo23– the handle mounts (fig. 4d, right) are owls comparable with the bird’s heads on the top of the linchpins from Manching, Ldkr. Pfaffenhofen24 which more specifically may represent respectively the eagle owl (Bubo bubo bubo) and a falcon or kestrel (Falco sp.) (fig. 4f). Down the back of the owls in low relief is a late ‘Vegetal’ tendril which in two dimensions would not be out of place on a ‘Hungarian’ style sword scabbard. The placid-looking bovines of Braa have the same slick-backed hair –similar to striations on the owls– that we have just noted on other pieces of this group and their closest cousin is a little bronze ring handle in the British Museum once in a private collection in Mâcon (Saône-et-Loire)25 (fig. 4g); the lipped ring of Mâcon is similar to that of the larger Brno-Maloměřice ring handle.

Musée d’Archéologie Nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye

(photo J.V.S. Megaw).

(left) Bronze on iron terret. D. 65 mm. Musée d’Archéologie Nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye (photo Inge Kitlitschka-Strempel);

(right) Bronze and iron linch-pin. Width 85 mm.

(left) Bull’s head. W 65 mm;

(right) Swivel mount with owl’s head. Max. W 62 mm.

Forhistorisk Museum, Moesgaard-Aarhus

(photos courtesy National Museum, Copenhagen).

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

(photo Crown copyright reserved).

Archäologische Staatssammlung, Munich

(photo J. Bahlo).

(above) Ring-handle and detail of head. Max. L 115 mm;

(below) mount. W 56 mm.

Moravské Zemské Muzeum, Brno.

Whole ring and mount, photos : M.Havelka; detail of ring, photo : J.V.S. Megaw.

Features of the fantastic animals which make up the main openwork of the Brno-Maloměřice flagon mountings, fit well into the general ‘Disney’ zoo and also exhibit typically Celtic elusive imagery –the main figure with up-sweeping horns which, depending on view-point, is either a bull or a stag while the ring handle (fig. 4h, above) clearly terminates in the head of a flamingo, perhaps the migratory Phoenicopterus ruber roseus while the base of the ring incorporates, reversed, an ambiguous long-beaked creature26. Quite out of the normal range of ‘Plastic’ stylistic conventions is mount n°3, the double-headed piece placed in the most recent reconstruction on the foot of the flagon. While double heads, though not common, do occur in early Celtic art the exceptional degree of realism is a throwback to such pieces as the basal handle mount of the Waldalgesheim spouted flagon and the silver Scheibenhalsring also supposedly from Mâcon27. Rupert Gebhard’s28 claim of influence from Hellenistic metalwork seems more ingenious than plausible and one is inclined to suggest instead that one is looking at an almost unparalleled phenomenon in early Celtic art, a portrait or rather, as here, a double portrait. In parenthesis, it can be noted that the theory contained in the splendidly illustrated study by Kruta and the Italian photographer Bertuzzi29 that the form of the Brno-Maloměřice mounts was determined by plotting the position of the planets as they would have been on 14 June 280 BC during the Celtic feast of Beltain is intriguing but again basically unbelievable.

Another find from the Brno-Maloměřice cemetery is the massive cast armring from the –presumably– female grave n°31 dated to a later phase of La Tène B230. This belongs to a class of ‘Plastic’ decorated rings centred on Moravia and Bohemia which Kruta31 has regarded as dating to a later phase of this ‘style’, several of which have the main decoration on opposing segments of the ring’s circumference as with that from grave 31. Notable are the face-like forms constructed from a stylized palmette (fig. 4i). This is a classic example of the ambiguous formulations which Jacobsthal nicknamed the ‘Cheshire style’ and which we characterised as a feature of two earlier and related groups of armrings and other objects32; the stylistic affinity with the Varna bronze is clear.

In the absence of any really good evidence for the locations of actual manufacturing centres for these items and thus the need to rely on the uncertain tools of stylistic analysis, several writers –including ourselves33– have placed the origin of this group in Central Europe with others, such as André Rapin and Luc Baray34, indicating a separate development in the Paris Basin contra Nathalie Ginoux35. Ginoux, taking a middle road, argues for the chariot-using warrior communities of the latter region having borrowed certain metalworking techniques from Central Europe; it should be added that there is something of a circular argument in her citing Mezek as an aid for dating the ‘Plastic’ style in the Paris Basin. Certainly, as the previous paragraphs should make plain, there seem to be close stylistic parallels represented by objects far distant in location. Indeed, there remain many unanswered questions when discussing this fascinating group of material. For example, irrespective as to its origin, the Braa cauldron must have travelled far before its dismantling and deposition. Klindt-Jensen36 was surely right to draw attention to the significance of the Elbe as a main route from Central Europe to the north. And here the detail of the combed-back hair motif also mentioned in connection with the Paris mounts is also found on a fine –but unfortunately incomplete– ‘Plastic’ style brooch from inhumation grave 10 of a flat cemetery at Villeneuve-la-Guyard (Yonne)37.

Two other bronzes seem further to weigh the balance of evidence in favour of north-eastern France being a key area for the development of this group of the ‘Plastic’ style. First is the mount from a La Tène C chariot grave at Attichy ‘La Maladrerie’ (Oise)38 (fig. 4j). Excavation in 2009 at the site has revealed another two chariot burials and other high status graves. Although the eyes of this little monster lack the ridged outline, the shape of the nose and the snout –not to mention the horn-like appendages or are they attenuated legs?– certainly recall the Varna mount. The second piece is the girdle-hook in the form of a grotesque face from a woman’s burial, grave 17 of the cemetery of Loissy-sur-Marne ‘La Vigne aux Morts’ (Marne) (fig. 4k). An old find, as Kruta (1987) notes, the face has close affinities with one of the Brno-Maloměřice mounts (fig. 4h, right) which one can read as a contorted figure with legs and head-dress –or is it another owl? As so often in Celtic art the form is ambiguous and certainty elusive.

Musée Antoine Vivenel, Compiègne

(photo Christian Schryve).

Musée des Beaux-arts et d’Archéologie, Châlons-en-Champagne

(photo J.V.S. Megaw).

There is one other piece in the Varna Museum of Archaeology which may offer a hint of further bronzes of undoubted western origin waiting to be studied. This is a cast roundel tentatively identified as a chariot mount39; its overall composition, spiral ornamentation and domed form have parallels in decorative roundels on shields and spears dated to La Tène B2 and found in warrior graves in France and the Czech Republic, two areas which seem to have had many points of contact, not least with regard to our ‘Disney’ style40.

It should also be noted that the Varna Museum of Archaeology holds a number of other finds which, though yet again without a more specific provenance beyond ‘north-eastern Bulgaria’, include examples of the so-called ‘false filigree’ technique of lost-wax casting41. False filigree is concentrated in Central Europe, notably from Bohemia to Hungary, and is to be found mostly on armrings and brooches dated to La Tène B2. Miklós Szabó42 has suggested that the technique developed first in the Balkans and then was disseminated westwards, notably following the period of the Celtic invasions. Also in the Varna collections, is a brooch with a foot in the form of a curved-beaked monster43. This is a specifically Hungarian form of the La Tène B1 Münsingen-Duchcov horizon44 and points to an earlier period of contact.

There is one last salutary parallel to make and one which underscores the problems of attribution based on stylistic considerations alone. From a presumed male inhumation burial, grave 150/1 on the Dürrnberg-bei-Hallein (Salzburg), comes a small Maskenfibel with two grotesque heads45 (fig. 4l). Exhibiting that skill in the lost-wax process which was so much a feature of early La Tène smithing techniques, both faces of the brooch are basically rectangular in form with a rectangular nose, oval eyes emphasised by an encircling ridge –and small horns, all features of our Varna head. The Dürrnberg brooch is clearly of La Tène A date and thus is around a century earlier than the La Tène B2-C1 material we have been examining here!

The question of La Tène discoveries in Bulgaria (JA, EM)

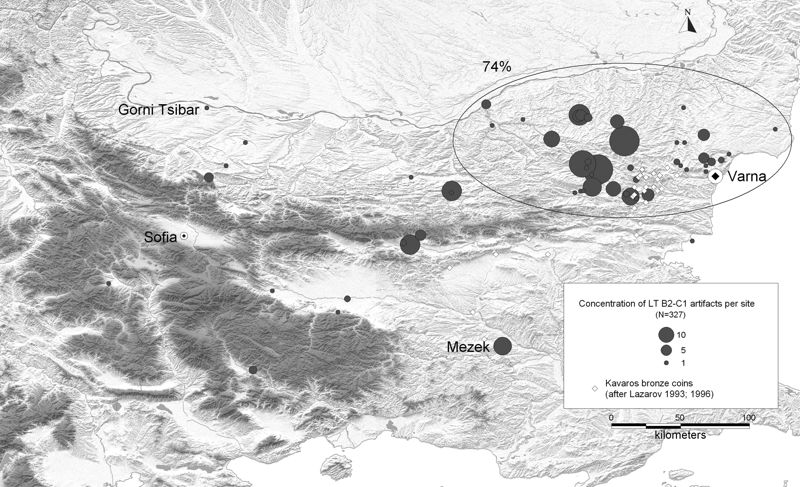

On balance, the stylistic argument just presented suggests that the mount is most likely to have been contemporary with the period of the historic Celtic migrations into Thrace in the early decades of the third century BC46. The mount belongs to the chronological group of some 300 objects of La Tène B2-C1 which have been collected in the course of preparing a thesis focusing on the whole region of Bulgaria47 (fig. 5). This corpus of early La Tène-type material found in Bulgaria consists of ornaments (brooches, arm- and foot-rings), weapons (swords and their scabbards), chariot fittings and some pottery which have close typological parallels in Central and Western Europe. All these discoveries including the Varna head, augment a group which until now has been marked only by a few finds48 such as the chariot fittings from Mezek and the gold torque from Gorni Tsibar (Montana) found near the Danube49, which, given its relationship to the ‘Waldalgesheim’ or ‘Vegetal’ style of the later fourth century BC, is amongst the earliest of definitively La Tène objects to have been found in Bulgaria.

There are, however, admitted difficulties with this corpus. Most of these discoveries are isolated finds. No ‘true’ Celtic –that is, early La Tène– cemetery or settlement is currently known and at present the majority of the La Tène finds discovered through regular archaeological investigations come from sites which a priori are indigenous to the area.

Higher concentrations of material appear in the fortified ‘Thracian’ settlements of Sboryanovo (Razgrad), Seuthopolis (Plovdiv), Arkovna (Varna) and Tsarevets (Veliko Tarnovo)50. All these sites show strong Hellenistic influences, except Tsarevets (Veliko Tarnovo) which has close parallels in the Carpathian Basin, Bohemia and Moravia. As to funerary evidence, La Tène-type artefacts come from tumuli associated with high-ranking burials. They appear for example in the barrow cemeteries of Sboryanovo (Isperih), Seuthopolis (Plovdiv), Banovo (Varna), Branichevo (Shumen), Madara (Shumen), Mezek (Haskovo) and Plovdiv51. Most of these burials are feminine and may be, at most evidence, of high-ranking women from Central and Western Europe married within the Thracian élite. In Plovdiv a warrior cremation with a deliberately deformed La Tène sword associated with an early La Tène fibula and more than twenty Greek and local pottery vessels is the only example of a potentially La Tène warrior grave of the beginning of the third century BC52.

The use of this scattered evidence to reconstruct a Celtic presence in Thrace is thus problematic. Were these La Tène artefacts diffused through commercial or migratory channels? Are these local products copying the new fashions from the West? Are they traces of a small group of people (craftsmen, mercenaries and the results of inter-marriage) or relics of a Western European Celtic population? This debate goes far beyond our territory and period of study and requires a careful examination of individual contexts –where they exist53. In the present case, the interpretative models are certainly numerous and not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Quantitatively, it appears that the majority of the ‘early’ La Tène remains from LT B2-C1, which may be associated with the historical settlement of the Celts in Thrace, are concentrated in north-eastern Bulgaria54 (fig. 6). The distribution of these finds seems significant as is supported by the fact that nearly all of the bronze coins of Kavaros, the last Celtic king of Tylis, are discovered in the same region55.

artefacts discovered in Bulgaria as at January 2010.

The majority (n=242 or 73 %) are concentrated in north-eastern

Bulgaria in the same area as are the largest

concentration of Kavaros bronze coins

(illustration J. Anastassov).

Based on these facts, the hypothesis of the location of a Celtic kingdom in an area between the Balkan Mountains, the Black Sea and the Danube is more than credible. This identification is corroborated by classical literary sources that emphasize the penetration of Celtic groups from the north of the Balkan Mountains56. The most significant evidence concerns the Celtic troops massacred at Lysimachia in 278/ 277 BC by Antigonos II Gonatas, who had previously conquered the territory of the Triballi and the Getae57. Their displacement from the north-east to the south-east Balkan Peninsula would necessarily imply crossing the Balkan Range. The concentration of most of the archaeological and numismatic discoveries at one of the most important crossing points of the Balkan Range, which is moreover in territory considered to have been settled by the Getae, can hardly be a coincidence.

Given these observations, the traditional location of an area of Celtic settlement in the extreme south-east of the Balkan Peninsula –in the Thracian Plain, around the Strandja Mountain or near Byzantium– is difficult to accept. But this demands a wider discussion than can be offered here. Suffice it to observe that future research should be primarily concentrated in north-eastern Bulgaria, in other words in the region where the Varna head was discovered.

Acknowledgements

JVSM and MRM wish to put on record their thanks to the many colleagues who, as part of a larger project, have over the years allowed the first-hand study of the material discussed in the present paper. The text of our paper remains substantially as submitted in December 2010.

References

- Anastassov, J. (2006): “Objets laténiens du Musée de Schoumen (Bulgarie)”, in: Sirbu & Vaida, dir. 2006, 11-50.

- Anastassov, J. (2007): “Le mobilier laténien du Musée de Ruse (Bulgarie)”, Известия. Регионален Исторически Музей – Русе XI, 165-187.

- Anastassov, J. (2008): “Représentation d’une épée laténienne sur le tombeau de ‘Ginina Mogila’ à Sboryanovo (Sveshtari/ Bulgarie)”, in: Gergova, dir. 2008, 175-181.

- Anastassov, J. (2012): Vestiges laténiens de Bulgarie (IVe-Ier s. av. J.-C.). De l’archéologie à l’histoire de la migration des Celtes en Thrace,, Thèse de doctorat, Université de Genève, Académie bulgare des Sciences, Geneve-Sofia.

- Anastassov, J. and N. Torbov (2008): “Le groupe “Padea-Panagjurski Kolonii”: réexamen des ensembles funéraires des IIe et Ier s. av. J.-C. du nord-ouest de la Bulgarie”, in: Sirbu & Stinga, dir. 2008, 95-107.

- Atanassov, G. (1992): “Erdanlagen vom 3.-2. Jh. v. Chr. aus der Region des Dorfes Kalnov, Bezirk Sumen”, Izv. na Istoricheskiia Muz. Sumen, 7, 5-44.

- Binding, U. (1993): Studien zu den figürlichen Fibeln der Frühlatènezeit . Universitätsforschungen zur prähistorischen Archäologie, 16, Bonn, Rudolf Habelt.

- Borhy, L., dir. (2010): Studia celtica classica et romana Nicolae Szabó septuagesimo dedicata, Budapest.

- Bospatchieva, M. (1995): “Mound burial in the Hellenistic necropolis of Philippopolis”, Известия на музеите от южна България, 21, 43-61.

- Bouzek, J. and L. Domaradzka, dir. (2005): The Culture of Thracians and their Neighbours. Proceedings of the International Symposium in Memory of Prof. Mieczysław Domaradzki, with a Round Table “Archaeological Map of Bulgaria”, BAR Int. Series 1350, Oxford.

- Buchsenschutz, O. (2001): Les Celtes de l’Âge du fer dans la moitié nord de la France, Paris.

- Buchsenschutz, O. (2007): Les Celtes de l’âge du Fer, Paris.

- Buchsenchutz, O., A. Bulard and T. Lejars, dir. (2005): L’âge du Fer en Île-de-France, XXVIe Colloque de l’AFEAF, Paris-Saint-Denis, 9-12 mai 2002, RACF Suppl. 26, Tours, Paris.

- Cullin-Mingaud, M., M. Doncheva and C. Landes, dir. (2006): Des Thraces aux Ottomans. La Bulgarie à travers les collections des musées de Varna, Montpellier.

- Čižmářová, J. (2005): Keltské pohřebiště v Brne-Maloměřích – Das keltische Gräberfeld in Brno-Maloměřice, Pravěk suppl. 14, Brno.

- Dobrzańska, H., V. Megaw and P. Poleska, dir. (2005): Celts on the Margin. Studies in European Cultural Interaction 7th Century BC – 1st Century AD. Dedicated to Zenon Wożniak, Kraków.

- Домарадски, M. and В. Танева (1998): Тракийската култура в прехода към елинистическата епоха, Беллопринт, (Емпорион Пистироc, II), Септември.

- Duval, A. and J.-C. Blanchet (1974): “La tombe à char d’Attichy (Oise)”, BSPF, 71, 401-408.

- Emilov, J. (2005): “Changing paradigms: Modern interpretations of Celtic raids in Thrace reconsidered”, in: Dobrzańska et al., dir. 2005, 103-108.

- Emilov, J. (2007): “La Tène finds and the indigenous communities in Thrace. Interrelations during the Hellenistic period”, Studia Hercynia, 11, 57-75.

- Emilov, J. (2010): “Ancient texts on the Galatian royal residence of Tylis and the context of La Tène finds in southern Thrace. A reappraisal”, in: Vagalinski, dir. 2010, 67-87.

- Enilov, J. and J.V.S. Megaw (2012): “Celts in Thrace? A re-examination of the tomb of Mal Tepe, Mezek with particulat reference to the La Tène chariot fittings”, Archaeologia Bulgarica, 16:1, 1-32.

- Fitz, J., dir. (1975): The Celts in Central Europe. A II. Pannonia-konferencia aktái – Papers of the II. Pannonia conference, Alba Regia 14, Székesfehérvár.

- Fol, A. (2001): “The chariot burial at Mezek”, in: Moscati, dir. 2001, 384-385.

- Gebhard, R. (1989a): Der Glasschmuck aus dem Oppidum von Manching, Die Ausgrabungen in Manching 11, Stuttgart.

- Gebhard, R. (1989b): “Zu einem Beschlag aus Brno-Malomerice – Hellenistische Vorbilder keltischer Gefässappliken”, Germania, 62, 566-571.

- Gergova, D., dir. (2008): Phosphorion. Studia in Honorem Mariae Cicikova, Sofia.

- Georgiev, V., B. Gerov, V. Tcipkova-Zaimova, N. Todorov and I. Velkov, dir. (1978): Studia in Honorem Veselin Beševliev, Sofia.

- Ginoux, N. (2009): Élites guerrières au nord de la Seine au début du IIIe siècle av. J.-C. La nécropole celtuque du Plessis-Gassot (Val-d’Oise), RdN Hors série, Collection Art et Archéologie 15, Villrneuve-d’Ascq.

- Hänsel, B. and E. Studeníková, dir. (2004): Zwischen Karpaten und Ägäis: Neolithikum und ältere Bronzezeit; Gedenkschrift für Nemejcová-Pavúková. Internationale Archäologie: Studia honoraria 21, Rahden, Westf., Leidorf.

- Jacobsthal, P. F., (1940): “Kelten in Thrakien”, Epitymbion Christou Tsounta. Archeion tou Thrakikou Laographikou kai Glossikou Thesaurou 230, 391-400.

- Jacobsthal, P. F. (1944): Early Celtic art, Oxford.

- Kaenel, G. (1993-94): “Objets, parures, société, politique…”, Bulletin du Centre Genevois d’Anthropologie, 4, 23-41.

- Kaenel, G. (2007): “Les mouvements de populations celtiques: aspects historiographiques et confrontations archéologiques”, in: Mennessier-Jouannet et al., dir. 2007, 385-398.

- Klindt-Jensen, O. (1953): Bronzekedeken fra Braa. Jysk Arkaeologisk Selskabs Skrifter 3, Aarhus.

- Krämer, W. and F. Schubert (1979): “Zwei Achsnägel aus Manching: Zeugnisse keltischer Kunst der Mittellatènezeit”, Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, 94, 366-389.

- Kruta, V. (1975): L’art celtique en Bohême: les parures métalliques du Ve au IIe siècle avant notre ère, Bibliothèque de l’École des Hautes Études 324, Paris.

- Kruta, V. (1987): “Le masque et la palmette au IIIe s. avant J.-C., Loisy-sur-Marne et Brno-Malomerice”, EC, 24, 15-32.

- Kruta, V. and D. Bertuzzi (2007): La cruche celte de Brno: chef-d’oeuvre de l’art, miroir de l’Univers, Dijon.

- Lazarov, L. (1993): “The Problem of the Celtic State in Thrace (On the Basis of Kavar’s Coins from Peak Arkovna)”, Bulgarian Historical Review, 2-3, 3-22.

- Lazarov, L. (2006): “New findings of Cavar’s coins and Celtic materials from the archaeological complex of Arkovna”, in: Sirbu & Vaida, dir. 2006, 167-182.

- Lejars, T. (2005): “Le cimetière celtique de La Fosse Cotheret, à Roissy (Val-d’Oise) et les usages funéraires aristocratiques dans le nord du Bassin Parisien à l’aube du IIIe siècle avant J.-C.”, in: Buchsenchutz et al., dir. 2005, 73-83.

- Meduna, J., I. Peškar, with O.-H. Frey (1992): “Ein latènezeitlicher Fund mit Bronzebeschlägen von Brno-Maloměřice (Kr. Brno-Stadt)”, Bericht der Römisch-Germanischen Kommission, 73, 182-267.

- Megaw, J. V. S. (1962): “A bronze mount from Mâcon: a miniature masterpiece of the Celtic Iron Age reappraised”, Antiquaries Journal, 43, 24-29.

- Megaw, J. V. S. (1965-1966): ‘Two La Tène finger rings in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London: an essay on the human face and Early Celtic Art”, Praehistorische Zeitschrift, 43-44, 96-166.

- Megaw, J. V. S. (1967): “Ein verzierter Frühlatène-Halsring im Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York”, Germania, 45, 59-69.

- Megaw, J. V. S. (1970): “Cheshire Cat and Mickey Mouse: analysis, interpretation and the art of the La Tène Iron Age”, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 36, 261-279.

- Megaw, J. V. S. (1981): “Une volière celtique: quelques notes sur l’identification des oiseaux dans l’art celtique ancien”, RAE, 32, 137-143 (= Études offertes à Jean-Jacques Hatt, I, Dijon).

- Megaw, J. V. S. (2004): “In the footsteps of Brennos? Further archaeological evidence for Celts in the Balkans”, in: Hänsel & Studeníková, dir. 2004, 93-107.

- Megaw, J. V. S. (2005): “Celts in Thrace? A reappraisal”, in: Bouzek & Domaradzka, dir. 2005, 209-214.

- Megaw, M. R., J. V. S. Megaw, N. Theodossiev and N. Torbov (2000): “The decorated La Tène sword scabbard from Pavloche near Vratsa: some notes on the evidence for Celtic settlement in Northwestern Thrace”, Archaeologia Bulgarica, 4:3, 25-43.

- Megaw, R. and V. Megaw (2001): Celtic art. From its beginnings to the Book of Kells, London.

- Mennessier-Jouannet, C., A.-M. Adam and P.-Y. Milcent, dir. (2007): La Gaule dans son contexte européen aux IVe et IIIe siècles avant notre ère, Actes du XXVIIe Colloque de l’AFEAF, Clermont-Ferrand, 29 mai-1er juin 2003, Lattes.

- Mircheva, E. (2006): “Mobilier funéraire d’une tombe de Bulgarie du Nord-Est”, in: Cullin-Mingaud et al., dir. 2006, 116-117.

- Mircheva, E. (2007): “La Tène C Fibulae kept in Varna Archaeological Museum”, in: Vagalinski, dir. 2007, 65-72.

- Moscati, S., dir. (2001): The Celts, London.

- Moser, S. (2010): Die Kelten am Dürrnberg. Eisenzeit am Nordrand der Alpen. Schriften aus dem Keltenmuseum Hallein, 1, Keltenmuseum, Hallein.

- Müller, F. (1989): Die frühlatènezeitlichen Scheibenhalsringe, Römisch-Germanische Forschungen 46, Mainz.

- Müller, F., dir. (2009): Art of the Celts 700BC to AD700, Brussels.

- Nachtergael, G. (1977): Les Galates en Grèce et les Sôtéria de Delphes: recherches d’histoire et d’épigraphie hellénistiques, Mémoires de la Classe des Lettres série 2, 63, 1, Bruxelles.

- Olivier, L. (2001): “Une nouvelle acquisition au Musée des Antiquités nationales: les tombes à char de Roissy ‘La Fosse Cotheret’ (Val-d’Oise)”, Antiquités nationales, 33, 19-20.

- Olivier, L. (2008): “Les codes de representation visuelle dans l’art celtique ancien: une lecture de la plaque au dragon de Cuperly (Marne)”, Antiquités nationales, 39, 107-119.

- Olivier, L. and P. Charlier (2008): “Masques et monstres celtiques: à propos d’un anneau passe-guide du IIIe s. av. J.-C. attribué à Paris (anomalies physiques et déformations plastiques)”, Antiquités nationales, 39, 121-128.

- Rapin, A. and L. Baray (1999): “Une fibule ornée dans le ‘Style plastique’ à Villeneuve-la-Guyard (Yonne)”, Gallia, 56, 415-426.

- Rustoiu, A. (2008): Războinici și socoatate în aria celtică transilvăneană, Interferente entice și culturale în mileniile IA. Chr. – IP. Chr. 13, Cluj-Napoca.

- Sandars, N.K. (1985): Prehistoric art in Europe, Harmondsworth.

- Schönfelder, M. (2002): Das spätkeltische Wagengrab von Boé (Dép. Lot-et-Garonne): Studien zu Wagen und Wagengräbern der jüngeren Latènezeit, Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Monographien 54, Mainz.

- Schönfelder, M. (2010): “Speisen mit Stil — zu einem latènezeitlichen Hiebmesser vom Typ Dürrnberg in der Sammlung des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums in Mainz”, in: Borhy, dir. 2010, 222-233.

- Sirbu, V. and D. L. Vaida, dir. (2006): Thracians and Celts. Proceedings of the International Colloquium from Bistrita, 18th-20 of May 2006, Cluj-Napoca.

- Sirbu, V. and I. Stinga, dir. (2008): The Iron Gates Region during the Second Iron Age: Settlements, Necropolises, Treasures. Proceedings of the International Colloquium from Drobeta-Turnu Severin (12-15 June 2008), Drobeta-Turnu Severin.

- Stoyanov, T. (2010): ‘The Mal-Tepe romb at Mezek and the problem of the Celtic kingdom in south-eastern Thrace’”, in: Vagalinski, dir. 2010, 115-119.

- Stoyanov, T., K. Nikov, M. Nikolaeva and D. Stoyanova, dir. (2006): The Getic Capital in Sboryanovo. 20 years of investigations, Sofia.

- Szabó, M. (1974): “Contribution à l’étude de l’art et de la chronologie de la Tène ancienne en Hongrie”, Folia Archaeologica, 25, 71-86.

- Szabó, M. (1975): “Sur la question du filigrane dans l’art des Celtes orientaux”, in: Fitz, dir. 1975, 147-166.

- Szabó, M. (1992a): “Les Celtes dans les Balkans”, La Recherche, 241, 296-304.

- Szabó, M. (1992b): Les Celtes de l’Est: le second âge du Fer dans la cuvette des Karpates, Paris.

- Szabó, M. (2001): “The Celts and their Movements in the Third-Century B.C.”, in: Moscati, dir. 2001, 303-319.

- Szabó, M. (2006): “Les Celtes de l’Est”, in: Szabó, dir. 2006, 97-117.

- Szabó, M. (2009): “L’art du pseudo-filigrane: Une technique des peuples celtiques d’Europe centrale”, Dossiers d’Archéologie, 335, 68-73.

- Szabó, M., dir. (2006): Les Civilisés et les Barbares du Ve au IIe siècle avant J.-C., Actes de la table ronde de Budapest, 17-18 juin 2005, Bibracte 12/3, Glux-en-Glenne.

- Taceva-Hitova, M. (1978): “Au sujet d’épées celtiques trouvées en Bulgarie”, in: Georgiev et al., dir. 1978, 325-337.

- Theodossiev, N. (2005): “Celtic settlement in north-western Thrace during the late fourth and third centuries BC: Some historical and archaeological notes”, in: Dobrzańska et al., dir. 2005, 85-92.

- Vagalinski, L., dir. (2007): The Lower Danube in Antiquity (VI c BC – VI c AD), International Archaeological Conference. Bulgaria-Tutrakan, 6.-7.10-2005, Sofia.

- Vagalinski, L., dir. (2010): In search of Celtic Tylis (III c BC), Sofia.

- Wożniak, Z. (1974): Wschodnie pogranicze kultury lateńskiej, Wydawnictwo Polskiej Wrocław – Warszawa – Kraków – Gdansk.

- Гергова, Д. and Р. Радев (1994): Историко-археологически резерват “Сборяново”. Западен могилен некропол. Обект на проучване – Могила 23 (септември 1994 г.), Rapport de fouille, Isperih.

- Димитров, Д., М. Чичикова, A. Балканска et Л. Огненова-Маринова, ed. (1984): Cевтополис. Том 1. Бит и култура, София, ИБAН.

- Домарадски, M. (1984): Келтите на балканския полуостров, София.

- Квинто, Л. (1985): “Келтски материали от III-I в. пр. н. е. в тракийското cелище Царевец”, Юбилеен cборник на възпитаниците от Исторически факултет на ВТУ „Cв. cв. Кирил и Методий”, XI, Пролетен колоквиум, Т. 1, 55-64.

- Лазаренко, И., Е. Мирчева et Д. Стоянова (2008): “Елинистическа гробница до c. Баново, Варненско”, in Маразов, И., ed.: Тракия и околния свят. Научна конференция-Шумен 2006. МИФ 14, София, Нов български университет, 75-102.

- Лазаров, Л. (1996): “Относно келтската държава с център Тиле в Тракия при Кавар”, Нумизматични изследвания, 2, 73-89.

- Филов, Б. (1937): “Куполните гробници при Мезек”, ИAИ, 11, 1-116.

Footnotes

- Buchsenschutz 2001; Buchsenschutz 2007.

- Buchsenschutz 2007, 155.

- Jacobsthal 1944, 97-103.

- Wozniak 1974; Домарадски 1984.

- Anastassov 2006; Anastassov 2007; Anastassov 2008; Anastassov & Torbov 2008; Anastassov 2012; Emilov 2005; Emilov 2007; Emilov 2010; Lazarov1993; Lazarov 2006; Megaw 2004; Megaw 2005; Megaw et al. 2000; Vagalinski 2010.

- Cullin-Mingaud et al. 2006; Mircheva 2006; Mircheva 2007.

- Inv. n° II. 11253; Cullin-Mingaud et al. 2006, cat. n°168.

- Müller 2009, 108.

- Jacobsthal 1944, 19 and 162.

- Megaw 1970, 275.

- Jacobsthal 1940; 1944, n°164 and 176; Emilov & Megaw 2012.

- compare Gebhard 1989a, 125-126; Домарадски & Танева 1998; Megaw 2004, esp. 96-97; Emilov 2005; Emilov 2007, esp. 59; Emilov 2010; Stoyanov 2010.

- Jacobsthal 1944, 152.

- Jacobsthal 1944, n°163 and 175; Schönfelder 2002, cat. n°58.

- Jacobsthal 1944, n°175.

- Megaw 1970, n°168.

- Sandars 1985, 371.

- Olivier & Charlier 2008.

- Olivier 2001; Lejars 2005.

- Klindt-Jensen 1953.

- Meduna, Peškar & Frey 1992; Čižmářová 2005, esp. 20-22, 125-126 and fig. 89-96; Kruta & Bertuzzi 2007.

- Megaw 1965-1966, cat. n°19, 120-125, fig.1-2, 4 and fig. 1, 5-8.

- Megaw 1981.

- Krämer & Schubert 1979.

- Megaw 1962.

- Meduna et al. 1992, fig. 4.

- Megaw 1967; Müller 1989, SHR97; Meduna et al. 1992, 258-262, fig. 39 and board 36.

- Gebhard 1989b.

- Kruta & Bertuzzi 2007, esp. 82.

- Čižmářová 2005, 21, 109 and fig. 68, 3.

- Kruta 1975, esp.75-89.

- Megaw 1957.

- e.g. Megaw &Megaw 2001, 140-144.

- Rapin & Baray 1999.

- Ginoux 2009, 125-136.

- Klindt-Jensen 1953, 79-81.

- Tapin & Baray 1999.

- Duval and Blanchet 1974; Schönfelder 2002, fig. n°44.

- Cullin-Mingaud et al. 2006, cat. n°180.

- Ginoux 2009, esp.93-96, 97.

- Cullin-Mingaud et al. 2006, cat. n°171-178; Anastassov 2012.

- Szabó 1975; Szabó 2009.

- Cullin-Mingaud et al. 2006, cat. n°164.

- Szabó 1974; see more recently Rustoiu 2008, 118 and fig. 58.

- Binding 1993, cat. n°365; Moser 2010, ill. on p.90.

- Nachtergael 1977; Szabó 1992a; Szabó 1992b; Szabó 2001; Szabó 2006; Taceva-Hitova 1978; Theodossiev 2005.

- Anastassov 2012.

- Fol 2001; Wożniak 1974; Домарадски 1984.

- Jacobsthal 1944, n°46; Megaw 2004, 96 and fig. 1a.

- Lazarov 2006; Megaw 2004 , fig. 9; Stoyanov et al. 2006; Димитров et al. 1984; Квинто 1985.

- Bospatchieva 1995; Димитров et al. 1984; Домарадски 1984, fig. 40, 42; Гергова & Радев 1994; Лазаренко et al. 2008; Филов 1937.

- Bospatchieva 1994.

- Kaenel 1993-1994; 2007.

- Anastassov 2012.

- Lazarov 1993; 2006; Vagalinski 2010; Лазаров 1996.

- Juv. 25.1; Paus. 10.19; Plut. 9; Sen., Nat., 3.11.2.

- Juv. 25.1.