Is the polychromy of the Libourne panel representative of other English panels, or is this one a case apart? Are the choices of colour and aesthetic choices common or unusual? An examination of the other English alabasters in the Aquitaine corpus will provide answers to these questions.

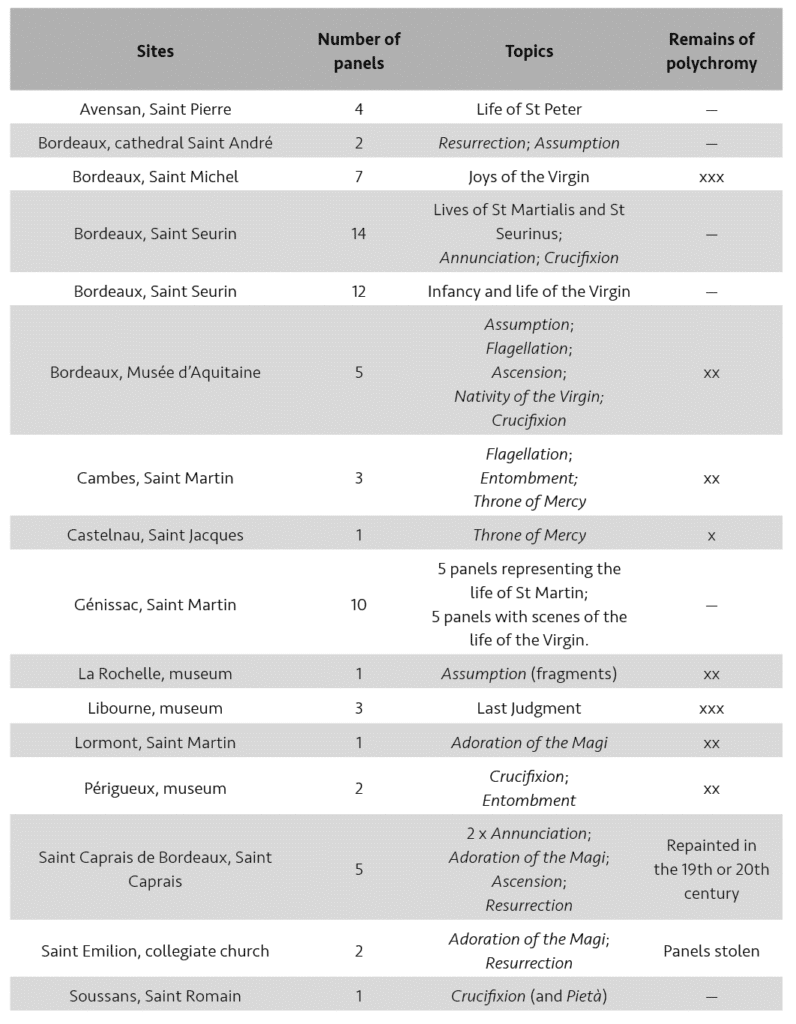

Among the hundred or so English alabasters from the Aquitaine region, only a limited number still show significant remains of polychromy. Indeed, many works, such as the two altarpieces of Saint Seurin in Bordeaux, the one in Génissac or the panels in Avensan, have been stripped and now appear entirely white.1 Other sets, such as the five panels preserved in Saint Caprais de Bordeaux, were completely repainted in the 19th or 20th century. If we also disregard the individual statues and consider exclusively the narrative panels, there are only about twenty artworks with usable chromatic information. These are, first of all, the eight medieval panels that make up the altarpiece of Saint Michel of Bordeaux (which also contain some repainting),2 as well as tablets preserved in Saint André of Bordeaux (1), Cambes (3), Castelnau (1), Lormont (1). To this should be added the panels in the Musée d’Aquitaine in Bordeaux (3), as well as those in the museums of Libourne (2 additional panels) and Périgueux (1). These twenty or so works were subjected to physico-chemical analyses (see table fig. 15).

In order to expand this limited corpus and increase its representativeness, a number of other works with well-preserved polychromy were examined and documented with the help of macro photographs. These supplementary elements include the collections of several French museums3 as well as the altarpieces of Nailloux, Montgeard (in the region of Toulouse) and Saint Nicolas du Bosc (Normandy). In a less systematic way, other panels were taken into account when it was possible to obtain colour photographs of sufficient quality.

A stereotyped polychromy

Contrary to our initial expectations, the range of colours selected by the alabaster carvers proved to be highly standardised as was the way in which they were distributed within the same panel.

Among the most significant and immediately identifiable elements of this standardised colour scheme is the arrangement of the backgrounds. On all the historiated panels examined, the lower part invariably shows an uneven terrain painted in green and decorated with ‘daisies’, while the upper part, dotted with gesso nodules on a smooth background, is always gilded. These green ‘meadows’ and golden skies characterise all the scenes examined, regardless of whether the event depicted took place inside a dwelling or outside. The flowers on the green background are highly stylised: a bright red dot painted in cinnabar is surrounded by five or six white dots in lead white. The appearance of stylised leaves, and even more so that of real flowers, as is the case at Saint Michel in Bordeaux, remains very rare (figs. 16 and 40).

The golden backgrounds of the upper part of the panels are always sown with gesso nodules (fig. 17). However, the size of the nodules and the density of the scattering vary. Occasionally, the gesso knots are arranged in a particular pattern, such as a flowerette: a large central knot is surrounded by five smaller ones (fig. 18). Even more rarely, the gesso nodules are aligned to form squares or rhombuses; exceptionally, they take the form of stylised leaves.4 In the vast majority of cases, however, the nodules, about five millimetres in diameter, are distributed randomly, though fairly evenly spaced, across the gold background.

On some panels, a pink area is inserted between the green ‘meadows’ and the golden sky. There are well-preserved examples in Saint Nicolas du Bosc (Annunciation, fig. 19; Adoration of the Magi). In the Aquitaine corpus, only the Flagellation in Cambes seems to present such a (very fragmentary) pink zone. The pink surfaces are always decorated with small darker dots, often purple, sometimes black or green. As these pink surfaces with darker dots also cover the tomb of Christ or the throne of God the Father (Throne of Mercy) or the Virgin (Coronation), it may be inferred that they represent stone surfaces – coloured marble? – and indicate an interior space.5

The colouring of the clothes is no less stereotypical than that of the backgrounds. Whether they follow the fashion of the time of the creation of the alabasters or are atemporal like the tunics and cloaks of the saints, and even the armour of the soldiers, they adopt the white colour of alabaster.6 The linings always show a frank monochrome colour, most often cinnabar red, less frequently blue, obtained either from indigo or from azurite, exceptionally they are green. Very often, even the soldiers’ armour has a cinnabar red ‘lining’.7 On some panels at least, the painters even went so far as to indicate the lining with a thin red (or blue) line in places where it was not actually visible, such as on the collar or on the fitted sleeves.8 With the notable exception of the angels, both clothing and armour are systematically hemmed in gold.9 The white obverse sides of dresses are frequently animated by a row of gold buttons on the bust; the slit in the dress is indicated by a red or blue line connecting these buttons (fig. 20).10

The obverse of coats and dresses may have various gold motifs, but as these fragile motifs have often disappeared, it is difficult to know whether they were widely used or not (fig. 21).11

The complexion of the figures is almost always distinguished by its immaculate whiteness (alabaster). Only the negative characters, such as the torturers of the martyrs or the Roman soldiers in the scenes depicting the Passion, have a pink complexion (fig. 22). Many studies of English alabasters indicate that the skin of the vile characters was painted brown or black. We have not come across any documented cases of this practice. Since lead white, which is a component of pink skin tones, darkens over time, this alteration may have resulted in brown or black tones on faces originally painted pink. The pink skin of negative figures may be overlaid with black or red-brown lines.12

The details of the faces are generally indicated as follows: the eyes, surrounded by fine lines of a purplish colour (red ochre), consist of a black pupil and a green-blue iris;13 the eyebrows are drawn in yellow ochre, sometimes in red ochre; the lips and nostrils are painted in cinnabar red (fig. 23).14 In the case of negative characters, certain colours differ: the eyebrows are painted in black or red ochre, but never in yellow ochre; strikingly, the irises are frequently coloured bright red, this colour being characteristic of the eyes of diabolic beings (fig. 24).15 In one of the panels of the Naples Passion Altarpiece, Pilate’s eyes are composed of a black pupil surrounded by a first golden circle and a second bright red circle, probably to indicate that he is possessed by the devil.16

Without exception, the hair of the holy figures was gilded. Ordinary men, even if they represent the elected as in Libourne or pious men devoted to Christ like Joseph of Arimathea, have less resplendent hair, painted in grey or red-brown. In view of these observations, the range of colours in the Libourne panel The Elected entering Paradise must be considered atypical, as it is exceptionally diverse, since the elected have yellow ochre, pale yellow and red ochre hair. The villainous figures, on the other hand, have black hair17 or, less often, reddish-brown hair with a purple tinge (fig. 25).18 Some characters, such as the Magi, may have golden hair on some panels, as in the case of the Adoration of the Magi in Lormont, and grey and brown hair on others.19 This variation of colours for the same person on different panels is nevertheless exceptional.

Some of the details of the panels show a particular colour scheme, specific to English alabasters. This is the case for the wings of the angels, the vast majority of which are painted in cinnabar red and adorned with feathers in the form of white teardrops decorated with a black dot (fig. 9, 19).20 Most often, these white feathers form a semé on the red backdrop; sometimes they are aligned in registers.21 The wings of the angels are also sometimes coloured in green, and perhaps also in white.22 However, these are exceptions to the rule. This is also the case with the St Michael of the Elected entering Paradise in Libourne, whose green wings on a gold background hardly seem to have any parallels.23

The colouring of the nimbus is also characteristic of English panels. Uncommonly large, they are not gilded as one might expect, but painted in red (cinnabar) and/or blue (indigo, less often azurite). Frequently, motifs painted in white decorate the residual lobes cut by the arms of the cross which ornate the haloes of God, Christ and, sometimes, the Holy Spirit (fig. 26). In fact, only God, Christ and the Virgin are endowed with haloes. The saints, like the apostles and angels, are only given this attribute when they are the main subject of an altarpiece.24

Unexpectedly, the cross of Christ was most often painted blue. In Aquitaine, only the Thrones of Mercy in Castelnau (azurite) and Cambes (indigo) show faint traces of this practice. The fact is, however, well established: perfectly preserved blue crosses decorated with white flowers containing a red heart appear in the altarpieces of Châtelus-Malvaleix (Creuse; 1 panel), Rabastens (3; fig. 27), Swansea (3) and the Passion Altarpiece (3), both in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Compans Altarpiece (1), the Passion Altarpiece from the abbey of Cluny (Berlin, Bodemuseum), the Rouvray Altarpiece in Rouen (2) and the Passion Altarpiece in Naples (3). In addition to these altarpieces, there are the isolated panels of the Crucifixion in La Trinité in Cherbourg, the Crucifixion (Cl 16599) and the Entombment (Cl 19322) in the Musée de Cluny in Paris, or a fragmentary Throne of Mercy in the National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik.

The general principles of colouring

To sum up, the study of the Aquitaine corpus as a whole confirms the limited number of colours that make up the usual range selected by the English painters, as was already apparent in the chapter dedicated to the Elected entering Paradise located in Libourne. The colours of most of the panels are even less diversified than those of the Libourne example. The latter, for example, has three different yellows, namely gold, yellow ochre and ‘citrine’ (pale yellow). The other Aquitaine panels generally display only one yellow, namely gold. Yellow ochre is employed elsewhere, but, apart from being used in some eyebrows and only as a component of the mixtion, intended to be covered with gold-leaf, and so it was not meant to be seen.

The same applies to the reds. While the Libourne panel shows three different reds, composed of cinnabar, red lead or ochre pigments, on other panels one hardly finds any other pigment than cinnabar. Red lead, like yellow ochre, was frequently deployed, but it is used almost exclusively as an undercoat for gilding. As red ochre was only applied for small lines or surfaces,25 such as the eyebrows, cinnabar tended to be the only shade of red utilised on the panels. The painter of the Nativity in the altarpiece of Saint Michel of Bordeaux, for example, applied cinnabar to colour the wings of the angels, the lining of the Virgin’s robe and that of one of the midwives, Joseph’s staff, the ‘poppies’ and the hearts of the flowers on the green background, and the lips and nostrils of the figures (fig. 28). Red ochre was only used for the eyebrows, the outline of the eyes and for the gilding mixtion. Red lead is only found on the inside of the Virgin’s crown, which is barely visible.26

The reduction of the colour range to one shade per colour also applies to blues and greens. As already mentioned, English painters had indigo or azurite pigments to produce blue paint. It is striking, however, that none of the panels examined contains both blue pigments at the same time;27 the painters chose either one or the other. Regarding the greens, they can be generated from copper-based pigments: physico-chemical analyses generally conclude that either copper acetate (verdigris) or copper resinate (copper acetate mixed with oil and Venetian turpentine) is present. According to our observations, only one or the other variant of green usually appears within the same panel. Within the Aquitaine corpus, only the panel of the Damned led to Hell in Libourne shows both types of green simultaneously (fig. 29).

In most English panels, the number of colours is almost as limited as the variety of pigments used. The painters did not try to increase their diversity by mixing pigments. In most cases, they did not even try to superimpose several partially transparent layers which, as in the Elected entering Paradise in Libourne, would have created a second shade of green (copper resinate on gold-leaf).28 Other Aquitaine panels rarely show such superimpositions,29and they seem to be just as infrequent on alabasters preserved in other regions.30

Mixtures of pigments do exist in the Aquitaine corpus, but they remain rare. Apart from pink, which is found quite frequently, blue, probably mixed with green (indigo and verdigris), was used to paint the reverse of Joseph’s cloak on the panel of the Adoration of the Magi at Lormont. The two sarcophagi of the Resurrection of the Dead in Libourne are painted pink for one, and light green for the other, the latter being composed of a mixture of indigo, organic yellow and lead white (fig. 30). Finally, some of the panels also show grey surfaces or orange-red (red lead and red ochre) – mixed colours to which we shall return later.

English alabasters and heraldry: two similar chromatic universes

Taken as a whole, the English panels are essentially made up of five colours, namely – in order of their quantitative importance – white (alabaster), golden yellow, cinnabar red, copper green and indigo blue, sometimes azurite. The use of a range limited to only a few basic colours is reminiscent of one of the most important symbolic universes of the Middle Ages, namely heraldry. Heraldry only allows these five colours, as well as black and sometimes purple, to the exclusion of all others.31 The way colours are used, for example, is similar in heraldry and in English alabasters. In both, the colours are used pure, without darkening, breaking or fading them – in other words, by discarding the shades. The objects or ‘charges’ on the coats of arms (crescents, towers, lions, etc.) are painted in a single highly saturated colour; as so with alabaster, the depiction thus foregoes any suggestion of volume, light and shadow that might enhance the relief of the sculpture itself. The attribution of a colour to an object is not conditioned by the aim of imitating nature: a lion can be black, an eagle red. In the field of a coat of arms, as in that of alabaster, adjoining surfaces always show very different chromatic values. In heraldry, there are even rules governing the combination of colours, including the rule of ‘the contrariety of colours’, which states that a charge painted white or yellow must be placed on a red, green, blue or black field, and vice versa.32 This rule does not exist in the strict sense for alabaster, as gold is frequently placed upon the white of alabaster, but painters widely adopted the principle by alternating ‘light’ colours (white and gold) with ‘dark’ colours (red, green, blue). The green meadows of the background, for instance, are embellished with flowers with white petals. The red wings of the angels – red is considered in heraldry to belong to the group of ‘colours’, which – in contrast to the metals argent and gold – can be assimilated to the dark colours – are adorned with white feathers, themselves decorated with a black dot. The sarcophagus in which Christ is placed is painted (clear) pink with (dark) brown or purple dots, etc.

The pictorial practices of heraldry also resemble those of English alabasters in the way coloured surfaces are combined. Both share the tendency to stylise objects (or ‘charges’), to multiply them while standardising their form, and finally to distribute them evenly over a monochrome surface (called a ‘field’ in heraldry). To mention just one well-known example: until the end of the 14th century, the King of France wore a coat of arms displaying a field of azure semé-de-lis Or, i.e. with densely arranged gold lilies, all identical to each other. The flowers of the green meadows or the feathers of the angels’ wings of the English alabasters are characterised by this same stylisation and simplification, the replication of the same form and its distribution as patterns of charges on a monochrome field.

The moral connotations of colour

Despite these similar uses, the pictorial conventions of heraldry are not always the same as those of English alabasters. While black (or ‘sable’) is fully included in the range of heraldic colours, this is not the case for the polychromy of alabasters. On most of them, black is used only for the pupils of the figures’ eyes, i.e. its occurrence is so limited in surface that it is almost invisible. There are exceptions, however. Within the Aquitaine corpus, the Libourne panel of the Damned led to Hell shows extensive areas of black, as well as other unusual colours, including an orangey-brown tone, but also purplish red and brown (fig. 31-34). The devil pulling the chained damned, the Hellmouth and a little devil riding on its snout are painted exclusively in these unusual colours.33 In contrast to all the other characters, their clothes – rudimentary loincloths – are not white, but orange-brown and highlighted with black lines. The fact that the men, even though they are damned, have the usual white (alabaster) complexion emphasises the particularly negative connotation of these dark or mixed colours, which are reserved for infernal beings. As we have already seen above, with regard to the colouring of the skin and hair of the vile characters, the colours of the English alabasters are not used neutrally, but carry a strong moral charge.

While it is easy to understand the diabolical symbolism that the Middle Ages attributed to black, it is perhaps more surprising to note that orange-brown (a mixture of red lead and red ochre) had the same connotation. As Michel Pastoureau has pointed out, this colour was considered in the Middle Ages to be the colour of lies and treachery; Judas, the archetypal traitor, was supposed to have had red hair.34 Although Judas’ hair is always black on English alabasters (in contrast to the golden hair of the other apostles; fig. 22), the red-brown colour had a negative connotation. According to some medieval authors, it was an assorted mixture of white, black and red – in other words, the three extremes of the medieval colour spectrum35 – which were mixed or ‘scrambled’.36 One author stated bluntly that it was the ugliest of all colours.37 It is therefore not surprising that this orangey-brown was chosen to paint dragons, the most diabolical of all creatures. Most often, the red-brown is there combined with black.38 In the same vein, the red-brown camail, often combined with black chain mail, worn by Roman soldiers – including those in the Resurrection of Saint Michel in Bordeaux – underlines their vile character (fig. 21).39

More surprisingly, the red-brown colour was also chosen for the ox of the Nativity or the Adoration of the Magi (fig. 35).40 Within the Aquitaine corpus, those of the Adoration of the Magi in Lormont and Saint Michel in Bordeaux still show some traces of it. Given the natural variability in the colour of different breeds of cattle the consistent selection of orange-brown for the one shown on the alabaster panels appears to be the result of a deliberate choice. Perhaps some of the exegetical texts on the Nativity help to explain this choice. According to the Gospel of Luke 2:7, Mary gave birth to Jesus, wrapped him in swaddling clothes and laid him in a manger. The prophecy of Isaiah 1:3 was linked to this phrase: “The ox knows its master, the donkey its owner’s manger, but Israel does not know, my people do not understand.” Some Church Fathers saw the ass in this prophecy as the symbol of the Gentiles(i.e. the converted pagans) who recognised the divinity of Christ, whereas they saw the ox as the symbol of the Jews who denied this divine nature and caused the death of Jesus.41 So it was maybe as a symbol of the Jews and their disbelief that the ox was given its orange-brown colour.

If the reddish colour of the ox has a negative connotation, the grey of the ass should in principle be charged with positive values.42 The use of this colour in other contexts seems to confirm that it has been taken in good part. Grey is used only for the hair and beard of Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus (in the Entombment scene, as in Cambes and Périgueux43), of the oldest of the Magi (in some of the Adorations of the Magi44) and of the centurion crying out in front of the crucified Christ: “Truly this was the son of God” (Crucifixion).45 In all cases, these are venerable and pious men of advanced age.

To this group should be added Joseph, whose hair and beard are also often painted grey.46 It should be noted that the grey tones are very diverse, more or less light or dark, and generally ‘coloured’. Grey is tinged with shades of blue, more rarely with green (fig. 36).

In short, the polychromy of the alabaster panels is characterised by standardised practices governing the use of colours. Few, highly saturated, juxtaposed and (rarely) superimposed according to a number of aesthetic principles, colours are assigned to people and objects according to a series of conventions. In this way, they create a visual code of a symbolic nature to express notions such as ‘good’ and ‘evil’. This strong symbolic codification distinguishes the world of alabasters from that of heraldry, where a given ‘charge’ can indiscriminately adopt one of the six ‘tinctures’.

Collective codifications and individual colour choices

The chromatic conventions we have just reviewed apply to almost the entire production of English alabasters that we have been able to take into account, i.e. more than a hundred works still showing significant remains of their medieval polychromy. Given that the English panels were produced by several generations of sculptors and, no doubt, in workshops far apart, this finding implies that the colouring of the alabasters was not a matter of free choice for each painter, but that all the alabaster makers used the same codified language – which, moreover, raises questions as to the way in which these conventions were fixed, transmitted and unanimously followed.47 It also follows that the patrons and clients, too, had little or no say in the choice of colouring of the works they acquired: whether purchased in Kirkjubær in Iceland, Lade in Norway, Bordeaux in France, Naples in Italy or Čara in Croatia, the works everywhere show the same decorative patterns.

The strong codification of the use of colour does not mean, however, that the painting of alabasters was done in a stereotyped or even mechanical manner. The colours of the angels’ wings, the nimbus and the cross of Christ, which are specific to English alabasters, illustrate the fact that their creators took the liberty to depart, at least in some cases, from the pictorial habits of Western Christian art. The generally observed conventions were not a rigid straitjacket, as the panels of the altarpiece of Saint Michel in Bordeaux or the Entombment in Périgueux illustrate. The painters refrained from the usual alternation between white obverse and red or blue reverse; the mantles of Christ and the Virgin have white reverse sides; in Saint Michel, these reverse sides are also strewn with black ermine spots (figs. 38, 39). Similarly, the decoration of the green meadows is not limited to the usual stylized ‘daisies’, but also introduces individual flowers, a kind of poppy, which are less strongly stylised and seen from the front (and not from above; fig. 40).

Not all the elements of the panels have a specific ‘colour code’, leaving it up to the painters to colour them as they wanted. This is true of the Flagellation column, which can be painted red (Cambes), pink (Rabastens), blue (Rouvray), purple (Paris48), grey-green (Lille,49 fig. 25), and may or may not have a speckled decoration – not to mention its capital and base, which are often adorned with other colours and ornaments.

The usual reduction of the palette to a few basic colours and the renunciation of mixtures do not prevent the creation of chromatic combinations that seem surprising or daring. This is the case with the beard and hair of Joseph of Arimathea in the Entombment of Rabastens, whose blue-grey colour is combined with lines of purple separating the strands (fig. 36). In some Coronations, the Virgin’s throne is painted in pink with green flecks; the same is sometimes true of Christ’s tomb chest.50 The clouds from which the angel of the Damned led to Hell in Libourne emerges consist of a blue-green backdrop with red parts and white ‘tears’ superimposed on it; in addition, green rays on a golden background emanate from it (fig. 29). The work of the alabaster painter was therefore not mechanical and purely repetitive. In any case, as with the iconographic composition of the scenes, no two alabaster panels appear to be completely identical in colour.

Notes

- A refutation of Francis Cheetham’s view that the altarpieces of Saint Seurin are not of English origin would go beyond the scope of this study. See Cheetham, 2003, XVI and 177; id. 2005, 51. Not all scholars share the opinion of the eminent English specialist; see for example Williamson 2010, 21, note 10.

- The ninth panel, depicting St. Joseph, is a 19th century pastiche. However, the original one, representing John the Evangelist, is probably the one now in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore (inv. no. 27.310). See Schlicht 2020.

- These are the Musée de Cluny and the Musée du Louvre in Paris, the Musée départemental de la Seine Maritime in Rouen, the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse and the Château Comtal in Carcassonne.

- For the arrangement of the nodules in rhombuses and squares, see the Passion Altarpiece inv. no. 50-1946 and the Annunciation with the Trinity in a wooden case, inv. no. A.193-1946, both in the V&A Museum, London, or the Resurrection in Hawkley Church, Hampshire, UK. The stylised leaves can be found on the large Passion altarpiece from Naples, formerly in the church of San Giovanni a Carbonara and now in the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, inv. no. A.M. 10816.

- There are, however, several panels belonging to the same altarpiece, preserved in the Musée de Cluny in Paris, which show such a pink area, although the scene depicted takes place outside, in this case the Arrest of Christ (inv. no. Cl 19345) and the Crucifixion (inv. no. Cl 19334).

- When an English alabaster panel shows coloured obverse sides of the garments, this is generally due to a recent repainting. This is the case, in Aquitaine, of the five panels of Saint Caprais near Bordeaux. Outside the Aquitaine region, we can mention, among many others, the St. Ursula from the Musée de Cluny in Paris (inv. no. Cl 19336), the altarpiece dedicated to St. James the Greater from Santiago de Compostela, the panels from the chapel of Haddon Hall in England, the Passion altarpiece of Coudray en Vexin, or a Crucifixion from the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lille (inv. no. A 2063). However, vestments with painted obverse sides were not completely unknown in the Middle Ages. See, for example, the kneeling donors at the bottom of the Throne of Mercy of Anglesqueville la Bras Long (Rouen, Musée des Antiquités, inv. no. D.91.7.3). Clerics wearing the habit may also have coloured obverse sides, as in the case of the St. Anthony in the La Selle altarpiece (in the Musée d’art, histoire et archéologie of Évreux) or the cardinals on the panel of Thomas Becket meeting the Popein the V&A Museum in London (inv. no. A.166-1946). As we shall see below, some apparently early panels also escape this convention, such as the Assumption in the Musée d’Aquitaine.

- This red ‘lining’ of the armour can be found, for example, on the panels of the Arrest of Christ and the Crucifixion in the Musée de Cluny in Paris (inv. no. Cl 19345 and Cl 19334), the Resurrection in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon, the panels of the Rouvray altarpiece (kept in the Musée départemental des Antiquités in Rouen, inv. no. R. 90.3.a-e) or on those of the Passion altarpiece in the Capodimonte Museum in Naples (inv. no. A.M. 10816).

- Given the fineness of these coloured lines, which increases the likelihood of their disappearance over time, it is not easy to know whether or not the lining of the sleeves and collars were systematically coloured. The altarpiece of Saint Nicolas du Bosc offers well-preserved examples, including the Virgin of the Annunciation. In the Aquitaine region, several figures on the panels of Saint Michel of Bordeaux still show, in a more or less fragmentary manner, red lines encircling the fitted sleeves of their dress. Remains also exist on the Entombment in Cambes.

- The robes or albs worn by angels usually only show gilding on the collar.

- These elements are very fragile and have very often disappeared. Among the well-preserved examples is the Rabastens altarpiece in the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse. The colour chosen for the line is that of the lining of the robe.

- Well-preserved examples include the figures of Christ and Pilate on a panel of the Rabastens altarpiece (Musée des Augustins of Toulouse), an apostle preserved in the Louvre (inv. no. OA 202), the apostles of the Apostolic Creed preserved in the V&A Museum in London (inv. no. 148 – 159-1922) or the executioners of the Carrying of the Cross from the altarpiece in Naples (Capodimonte Museum, inv. no. A.M. 10816). A few rare panels show motifs painted in red and black on the obverse of the mantles (Munkaꝥverá altarpiece in the National Museum of Copenhagen); on others, they are painted in red and blue (Adoration of the Magi and Assumption in the Ávila Cathedral Museum).

- The pink complexion distinguishes the torturers of the Flagellation of Cambes; it is better preserved on the Flagellations of the Musée de Cluny, on the soldiers of the various panels of the altarpieces of Rabastens (Toulouse, Musée des Augustins), of Rouvray (Rouen, Musée des Antiquités), of Naples (Capodimonte Museum) or of Plentzia (Spanish Basque Country). The men-at-arms of the Arrest of Christ in Lade (Norway) show black lines in superimposition (the faces have been at least partially repainted).

- Examples of irises are only very rarely preserved, and even less often documented in sufficient detail; most often, the blue irises are very fragmentary, and we have not been able to determine the nature of the pigment used (azurite?). Fairly well-preserved examples can be found in the Jewry Wall Museum in Leicester (Christ of The Resurrected appearing to Mary Magdalene), in the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse (Christ of the Crucifixion), in the Musée de Cluny in Paris (Christ of the Coronation of the Virgin, inv. no. Cl 19337), in the Burrell Collection in Glasgow (God the Father of the Annunciation), as well as in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon (Christ of the Resurrection).

- Almost intact examples can be found in Libourne (Resurrection of the Dead, inv. no. 02.1.44), in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon (Resurrection) or in the Metropolitan Museum in New York (Adoration of the Magi, inv. no. 25.120.485); the altarpiece of the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, with its exceptionally well-preserved polychromy, offers numerous examples, even if the irises seem to have disappeared in most cases. As for the nostrils painted in cinnabar red, only those of the Roman soldiers in the Resurrection and those of the Virgin of the Nativity in the altarpiece of Saint Michel de Bordeaux have been analysed.

- See the literary examples analysed by Logié 2000, including for example the description of the devil Astarot in the Roman de Thèbes, § 15: ‘les [oils] ot rouges come lepart / onc homme ne vit tant laide regarde (v. 2856-7)” [He had red eyes like those of the leopard/ no man ever saw such an ugly gaze].

- The eyes of the devil or the monsters are usually painted in black on a gold background. The face of Pilate is reproduced in Giusti 2013, 192.

- Within the Aquitaine corpus, the four soldiers in the Resurrection of Saint Michel of Bordeaux as well as the Herod in the Adoration of the Magi in the same altarpiece have black hair. The same applies to two of the torturers in the Flagellation at Cambes. Examples outside this corpus are too numerous to be listed here.

- This is true of two of the torturers of the Flagellation at Cambes.

- The grey and brown-haired Magi can be found, for example, on the panels of the Adoration of the Magi in the altarpiece of Saint Nicolas du Bosc, in the Metropolitan Museum in New York (inv. no. 25.120.485), or in the Castle Museum in Nottingham.

- Among the few works which, apart from the production of English alabastermen, show red angels’ wings with white feathers is a French ronde-bosse enamel depicting the dead Christ between the Virgin and St John (New York, Metropolitan Museum, inv. no. 17.189.931).

- The wings of the angels of the Cambes’ Throne of Mercy were probably adorned with white tears aligned in registers. The angels of the Throne of Mercy in the V&A Museum in London (inv. no. 901-1907) constitute a very well-preserved example of this arrangement, and the one in the Entombment Cl 19322 in the Musée de Cluny in Paris is another example.

- Green wings appear on the Entombment of St Catherine in Vejrum (Denmark); although the polychromy has certainly be retouched, it seems to faithfully reproduce the medieval painting. White wings with black teardrops appear on the Throne of Mercy in Montgeard (Haute-Garonne); as the panels in Montgeard are not free of repaints, it is not certain that this colouring is medieval.

- Similar wings apparently distinguish one of the angels of the Assumption, the feathered body of the angel of the Nativity, and the eagle of St John in the Möðruvellir altarpiece (Reykjavik, National Museum of Iceland). The altarpiece was repainted in an attempt to reproduce, more or less faithfully, the medieval polychromy.

- The vast majority of English altarpieces are devoted to the Passion of Christ or to a series of Marian scenes commonly referred to as the Joys of the Virgin. The altarpieces dedicated to saints – Catherine, John the Baptist, Peter, Martin, George, Edmund or several martyrs – do not always show them haloed. Thus, in the altarpieces dedicated to various martyrs, preserved in Gondreville in Picardy and in the Denver Art Museum, none of the saints is provided with one (only God the Father, who appears on the central panel of the two altarpieces, shows one). On the altarpiece of La Selle (kept at the Musée d’art, histoire et archéologie d’Évreux) dedicated to St. George and the Virgin, only the latter is distinguished by a nimbus. The five panels illustrating the life of Martin at Génissac, on the other hand, show the saint displaying a large halo. On the Gdansk altarpiece dedicated to John the Baptist, the Precursor is provided with one only on the central panel.

- Exceptions to this are the panels depicting executioners or torturers, often with reddish-brown hair, such as those of the Arrest of Christ or those of the Flagellation.

- The red of the letter ‘G’ on the angel’s phylactery could not be identified with certainty: organic red or perhaps lead red?

- To our knowledge, only a panel in Fuentarabia (Spanish Basque Country) depicting the Beheading of St Catherine apparently contains indigo and azurite at the same time. See Martiarena Lasa 2012, 166.

- Referring to Aristotle, Vincent of Beauvais stated (around 1240) that colours could not be mixed. Intermediate colours would be obtained by the transparency of the colours, non-miscible and one on top of the other. To illustrate this idea, Vincent of Beauvais evokes the example of fingernails: “And so we obtain the middle of the upper and the lower, as can be seen in a man’s fingernail, which has a translucent colour, completed by the colour of blood underneath. So, generally, with all intermediate colours.” Trans. after Hüe 1988, § 15. See also Pastré 1988, § 8 and 9, who insists on the superposition of white complexion and red cheeks (a rose petal on a lily) in medieval German authors; there is no mixing between the two colours.

- The scene of the Damned led to Hell, kept in the Musée de Beaux-Arts in Libourne (inv. no. 02.1.43), depicts an angel emerging from the clouds; the rays emanating from these clouds are painted in translucent green on a gold background. Christ’s crown of thorns in the Entombment in the Musée d’Art et Archéologie in Périgueux also shows a translucent green on a gold background.

- The Entombment (inv. no. CL 19322) from the Musée de Cluny in Paris features a thurifer angel with a green glaze on the neck against a golden background. This same technique was used for the Virgin and Child recently acquired by the British Museum (Pereira-Pardo et al. 2018, 8); the authors note ibid. that other examples exist in the collections of the V&A Museum in London. In the Munkaꝥverá altarpiece (Copenhagen, National Museum of Denmark), the gilded globe of Christ is partially covered with translucent green paint.

- Heraldry uses the often specific colour terms argent (white), or (yellow), gules (red), vert (green), azure (blue) and sable (black) to refer to these six colours. Some treatises on heraldry, such as that of the herald Sicille (c. 1435), admit a seventh colour, namely purpura, while insisting that its use remains rare.

- Heraldry distinguishes between two groups of colours, namely ‘metals’ (argent and or) and ‘colours’ (gules, vert, azure, sable, sometimes purpura). When a charge is placed on a field, their respective colours must not belong to the same group.

- The panels featuring negative characters, where the colour black is frequently used for beards, hair and shoes, display these colours regularly.

- See the suggestive passage in Pastoureau 2012, 221-230, part. 221 : “Depuis longtemps, en effet, la trahison avait en Occident ses couleurs, ou plutôt sa couleur, celle qui se situe à mi-chemin entre le rouge et le jaune, qui participe de l’aspect négatif de l’une et de l’autre et qui, en les réunissant, semble les doter d’une dimension symbolique non pas double mais exponentielle. […] Dans la rousseur médiévale il y a toujours plus de rouge que de jaune, et ce rouge ne brille pas comme du vermeil, mais au contraire présente une tonalité mate et terne comme les flammes de l’Enfer, qui brûlent sans éclairer”. [For a long time, in fact, betrayal had its colours in the West, or rather its colour, the one that lies halfway between red and yellow, which participates in the negative aspect of both and which, by bringing them together, seems to endow them with a symbolic dimension that is not double but exponential. […] In medieval freckles there is always more red than yellow, and this red does not shine like vermilion, but on the contrary has a dull, matte tone like the flames of Hell, which burn without illuminating.]

- Pastoureau 2012, 168 notes about the codification of liturgical colours: the system is built around the three ‘basic’ colours of early medieval Western culture: white, red and black, i.e. white and its two opposites.

- The poet Jean Robertet (d. 1502/1503), for example, calls this colour ‘riolé-piolé’, a variegation defined as follows: “Broille meslé de rouge, noir et blanc”. See Hüe 1988, § 6.

- Pastoureau 2012, 228.

- For some medieval authors, black and russet are so closely related that they use the same word, ‘brisus’, to designate both. See Hüe 1988, § 34, who refers to the glossary preceding the compilation of recipes on the art of painting by Jean le Bègue, dated 1431 (BnF Ms lat. 6741). Red and black dragons appear, for example, on the well-known group of St George slaying the dragon in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., or on the left side panel of the altarpiece in the Danish church of Borbjerg, also dedicated to St George.

- Among the many examples preserved outside the Aquitaine region, we should mention the panels of the Rabastens altarpiece (preserved in the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse), a Resurrection in the Musée de Cluny in Paris (Cl 19328) or the Crucifixion in the Compans altarpiece. Most often, the chain mail of the camail was schematically indicated with black paint.

- See the ox from the Adoration of the Magi in Saint Nicolas du Bosc, Anglesqueville la Bras Long and an isolated panel (the latter two preserved in the Musée départemental des Antiquités in Rouen, inv. no.D. 91.2 and 4503), or the ox from the Nativity Cl 23755 in the Musée de Cluny and from the altarpiece in Munkaꝥverá (National Museum in Copenhagen).

- Grousset 1884, 337-338.

- The ass in the Adoration of the Magi in Lormont and the ass in the Nativity in the Saint Michel altarpiece in Bordeaux still retain some traces of grey. Examples with better preserved polychromy can be found in the Nativity of the altarpiece from Munkaꝥverá (National Museum of Copenhagen), on the panel representing the same theme in the V&A Museum in London (inv. no. A.94-1946), or on the Adoration of the Magi in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, in the Ávila Cathedral Museum (Spain) or in the Metropolitan Museum in New York (inv. no. 25.120.485).

- Among the alabasters preserved outside Aquitaine, the Entombments in the Musée de Cluny Cl 19325, Cl 19322 and Cl 19324 show Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea with grey beards and hair.

- See the altarpiece at Saint Nicolas du Bosc and a panel in the Castle Museum, Nottingham (inv. no. NCM 1954-38).

- This phrase appears in the Gospel of Matthew, 27, 54 and in Mark, 15, 39 (“Vere filius Dei erat iste”). The text, which must have been inscribed on the phylacteries near the centurion in the Naples Passion Altarpiece (Capodimonte Museum, inv. no. A.M. 10816; only a few black letters are preserved) and on many other alabasters depicting the Crucifixion, has apparently only been preserved on the panel forming part of the Passion Altarpiece in the V&A Museum in London (“Vere filius dei”; inv. no. A.172-1946). The phylactery of the Crucifixion in the completely repainted altarpiece in Compiègne bears the inscription “Jesus Nazarenus rex Iudeorum”; this is most likely a restoration error. For the grey hair of the centurion, see among others the following Crucifixions: Rouvray altarpiece (Rouen, Musée départemental des Antiquités, inv. no. R. 90. 3c); Cl 19334 from the Musée de Cluny; A.9:1-1943 from the V&A Museum in London.

- This is the case with the Joseph of the Nativity in the altarpiece of Saint Michel in Bordeaux; however, the authenticity of the grey does not seem to be beyond doubt. Joseph’s hair is undoubtedly grey, for example, in the Adoration of the Magi in the Ávila Cathedral Museum.

- Most often, the alabaster panels seem to have been carved and painted by the same person. On this point, as well as on the puzzling question of the standardisation of the works and their colouring, see for example Schlicht 2019, 190-191.

- Paris, Musée de Cluny, inv. no. Cl 19347.

- Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille, inv. no. A 31.

- For the throne of the Coronation of the Virgin, see for example Cl 19337 of the Musée de Cluny in Paris; for the tomb chest, see for example Cl 19322 in the same museum.