This study1 aims to follow the paths of the audience towards and within ancient Greek theatres. It examines sculptures set up in and around ancient Greek theatres from one perspective: was the “decorative program” closely related to the circulation of the audience? In other words, how did the location of sculptured monuments facilitate, direct, slow, or even block movement around a theatre? Also, how did the monuments interact with the surrounding space? From the late Classical period and beyond, statues in theatres were placed in highly visible positions. Therefore it is worthwhile to consider Hellenistic theatres along with the statues that were in full view of the audience.

Theatres were public monuments of crucial importance in a Greek city and theatrical space was rich in religious, cultural, and political significance. This paper attempts multiple readings of space as social text along with readings of documents. It is furthermore necessary to examine if specific categories of evidence, for example honorific statues or choregic monuments, were always displayed in the same parts of the theatre. Textual evidence indicates if a particular rule was followed, if there were forbidden or restricted areas, and who decided where to place the sculptures. Conclusions will be drawn from case studies, and by comparing Classical and Hellenistic evidence from mainland ancient Greece.

Ancient Greek theatres have been the subject of many studies. Most examine the architecture of the monument or monumental complex, while others offer a review of drama, usually concluding that the literary evolution of Greek drama affected the development of theatral architecture2. The ever-increasing dissemination of drama during the fifth and fourth centuries is demonstrated by the spread of theatre-related iconography, dramatic texts, theatre buildings, dramatic festivals, and the choregic system. New studies of the particularly rich epigraphic, archaeological, and literary material have seriously challenged the prevailing view that theatral space in the fifth century was a circular playing space bordered by a large venue3.

The present paper will focus on movement inside ancient Greek theatres while highlighting the socio-historical aspect of the monument. In this study, when we talk about movement we refer to the people and the conditions of moving inside theatres, as well as around and towards them. The exploration of this interactive relationship between audience and theatral area will introduce further questions: was the “decorative program” of the monument closely related to circulation? How did the location of sculptured monuments facilitate, direct, slow, or even block movement in a theatre? Most significantly, did portraits and other life-sized statues in the theatres distract the audience from the performance? The impact of this visual and spatial relationship will emerge from the analysis of material and epigraphic records4.

Before continuing with the analysis of the material I would like to note that the study of epigraphic and sculptural finds from ancient Greek theatres can be problematic, especially concerning sculptural assemblages represented mostly by inscribed bases5. In most cases, their fragmentary state makes it difficult to establish a precise date and interpretation; results generally emerge only after considering the finds within their monumental and urban environment. Thus, the terms decorative or sculptural program must be used with caution. However, the theatres in Athens, Trachones, Delos, and Messene include important and interesting contexts, since statue bases, fragments of sculptures, reliefs, and choregic monuments were found within these complexes. The theatre of Athens preserves examples dated from the second half of the fourth century and throughout the Hellenistic period, but this is unusual. Although the practice of setting up statues in theatres increased throughout the fourth and third centuries, it reached a clear peak during the Imperial period6.

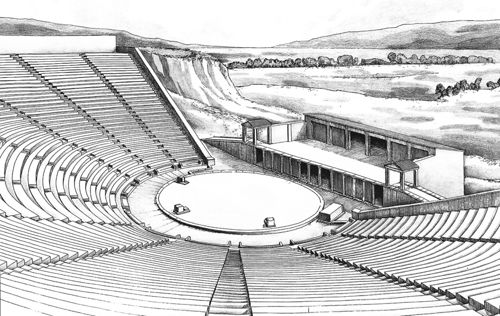

Greek theatre is generally considered as an architectural complex (and not just a building), composed, basically, of three separate elements: the auditorium, the orchestra, and the scene building. It is not necessary to re-examine here separately the architecture of the constituent parts of a Greek theatre, as long as, for the purposes of the present paper, we will follow the paths of the ancient audience, but in reverse: from the interior to the exterior, from the center to the periphery. Moreover, as John Ma points out aptly, “The theatre building, with its architectural unity, provides clear access ways and converging sightlines”7.

The architectural development of the theatre in Greece was a long process, beginning with the construction of the earliest wooden buildings in the Archaic and Classical periods, and culminating with the creation of permanent auditoria and stage buildings made of durable materials in the late Classical and Hellenistic periods8. It seems that the requirements of a massive audience and the changing uses of this kind of building led to the invention of new architectural forms for stone theatres. The koilon and the orchestra, forming the theatre-building, reached their fully developed form in the late Classical and Early Hellenistic periods, whereas the development of the stone stage-building is a Hellenistic phenomenon9. The purpose was to create architectural structures that maximized how well the audience could see and hear the productions. Thus, not all theatre buildings are consistent in their design, with a canonical layout of every part. Furthermore, in some cases the theatre’s architectural context (adjacent buildings or building complexes) determined the shape or the size of a theatre (e.g., Athens, Delphi, Thorikos, etc.).

During the second half of the fourth century, the theatre became part of Greece’s public monumental architecture10. At this time a theatre, located either in the heart of the political or sacred zone of a city, became an ἐπιφανέστατος τόπος11. The growing popularity of the structure and of the activities that took place in it attracted public and private honorands. Theatres became places where the very act of conferring honors on individuals or groups was a performative event. Usually on these occasions, statues and other sculpted monuments were erected at the edge of the orchestra12, at the intersection between the orchestra and the retaining walls13, and at the koilon and the parodoi14. The stage building itself was not used for displaying sculpture until the transition to Roman theatres, with the exception of the Hellenistic theatre of Priene15. Pausanias (2.7.5) saw the statue of Aratus (271-213) on the stage building of Sikyon’s theatre. The Achaean strategos was depicted with his shield, defending his hometown. The monument is completely lost but it was likely Hellenistic, probably erected soon after Aratus’s assassination by the Macedonians. This posthumous statue of a general in the theatre underlines the theatre’s function as a political gathering place, and at the same time reinforced the civic identity of the crowd16.

The orchestra

The orchestra was the main performance space, drawing all eyes towards it17. It was the earliest architectural part of the theatre and its form was determined by the first rows of seats, at least partially curved, and by the front of the stage building. Its shape – circular, semicircular, or trapezoidal – mattered little, provided it was suitable for dance and song18. The transition to performances on a raised proskenion dated by most scholars to the Hellenistic period is not widely accepted. However, we assume that performances were taking place primarily in the orchestra, but at that time a second performance space was also available19. The second space would be necessary because in some theatres, the available space of the orchestra was occupied by sculpted monuments and marble thrones.

Living benefactors were usually honored with permanent prohedria in the theatre20. The seats of honor could be located either at the front part of the seating area, as part of the koilon, or as independent thrones. Decrees or other epigraphic sources provide more information about their exact location (e.g., next to the priest of Dionysus in the decree SEG 36, 187), their form (e.g., thrones, as in the case of Antiochus in Megalopolis in the dedicatory inscriptions IG V2 450, 451, 452=SEG XXXVII 345), details about the public announcement of honors (IG IX, 2, 1230), the ritual of entrance and the occupation of these seats21, and the person who was responsible for accommodating the honored persons (ἀρχιτέκτων, IG II2 500, 33-36 and 512, 7-8 “κατανέμειν αὐτοὺς τόπον εἰς θέαν”)22.

Independent marble thrones on the orchestra appear in the Hellenistic theatres of Delos, Messene, Stratos, and Arcadian Orchomenus23. The prohedria thrones are often constructed of high-quality stone, and ornaments and profiles are often carved, presenting highly varied decorations. The most elaborate example comes from Oropos of Attica where five decorated marble thrones were erected in the orchestra during the first century BC (fig. 1 a and 1 b) The dedicatory inscription informs us that the priest Nikon dedicated these five marble thrones to Amphiaraos24. The inscription is engraved on all five thrones, emphasizing the honor attributed to the priest and commemorating him.

It is challenging to reconstruct the circulation path of members of the local elites in these theatres because they had to cross the orchestra to find their seats and, moreover, each throne was part of the orchestra’s space. The position of the prohedria obstructed the orchestra. Does this mean that the orchestra was unused space when the prohedria were installed, or that the inconvenience was overlooked as the position highlighted their importance? Angelos Chaniotis invites us to imagine a ceremonial procession of the honored towards their prohedria25. As their entrance was part of the spectacle, the honored elites entered the theatre separately from the public as a ritual that communicated the town’s gratitude.

Similar disruption occurred in the Hellenistic theatre of Argos, where a sculpted monument was placed at the center of the perimeter of the orchestra, in front of the first row of seats and just next to the stairways (fig. 2). It was probably a monument depicting Perilaos of Argos killing Othryadas from Sparta, referring to a battle of the sixth century BC26. A prominent place in the city’s theatre was chosen for this sculpture with its narrative power and clear political message.

Independent marble thrones and honorary statues were set up around the orchestra of Delos’s theatre during the third century BC. Three portraits and their bases were placed in front of the proskenion, covering some of the painted panels but preserving access to the main door of the building (fig. 3). The portraits included one private honorific monument by an Attalid ruler, one public honorific monument for the pipe player Satyros, son of Eumenes, and a third portrait now unidentified. The few examples of statues displayed in front of a Hellenistic proskenion, offering a frontal view of the sculptural decoration, could be considered as a predecessor to an elaborate scaenae frons27.

Fraisse & Moretti 2007, pl. 111, fig. 425 (aquarelle by T. Fournet).

The koilon

The Greek word theatron means « the seeing place » and describes the space reserved for the audience (or auditorium, in English). For early, semiorganized theatres, the theatron would be a natural slope where spectators could sit on the ground or stand (if the auditorium became crowded).

The lexicographer Photius mentions wooden seats in the Agora of Athens, their collapse around 499-496 BC, and their relocation to the sanctuary of Dionysus on the south slope of the Acropolis28. Beginning in the fifth century, we know of reserved seats for certain priests and magistrates at the sanctuary of Dionysus, and more comfortable seats at the base of and separate from the continuous benches of the auditorium. Because the theatral area was the terminal point of a procession-pompè29, does the placement of the reserved seats mean that the priests and magistrates were the last to enter the theatre, at the end of the procession? The priest entered the theatre together with the xoanon, the wooden image of Dionysus from Eleutherai. The xoanon was temporarily exhibited somewhere on the perimeter of the orchestra, probably beside the priest, and once the priest had taken his seat, it was time for the feast to start. We presume that the archontes, the choregoi, the members of the demos, and the theoroi had already entered following some sort of hierarchical order.

The god, depicted as a winged phallus, a pillar with painted details, or resembling Peisistratus, entered the crowded theatre and assured the divinity’s presence during the festivities30. The symbolic allusion to the advent of Dionysus Eleuthereus in Athens hosted by the legendary king Amphiktyon was clear. The procession ended in the theatre where the chorus performed round dances on the orchestra in front of the statue of Dionysus and his priest. The numerous portable images carried in the procession on feast days and then displayed in the theatre are attested even during the Roman period, reflecting a long-standing habit31.

But what about the circulation of the crowd? One can easily imagine ancient or even modern Greeks crowding the theatral space, entering or leaving the auditorium, all while simultaneously a spectacle was being performed32. It is interesting to note that in early theatres, the theatral areas were not delineated: there were no physical boundaries between them and the adjacent sacred zones (as at Ikarion33) or political-military zones (as at Rhamnous34). At Rhamnous and Ikarion, only the prohedria and a line of stelai bases indicate the boundary of the orchestra and the beginning of the auditorium. Later, stone public buildings allowed the invention of new forms that were more elaborated and better adapted to large audiences.

It is difficult to reconstruct the circulation system in ancient Greek theatres due to a) the fragmentary preservation of the theatres’ remains, b) the changes of their architectural design over long periods of use, and c) the different functions of the space. According to R. Frederiksen, the idea of the semicircular koilon is clearly the result of a growing popularity of the theatre35. Because of their steep incline, Greek stone theatres require vertical stairways (klimakes) radiating from an axis in the center of the orchestra and horizontal passageways linked to ramps or access stairways (what is usually incorrectly described by the term diazoma). But no Greek theatre before the construction of the theatre at Nicopolis36 presents an advanced circulation system for the spectators; this system was ultimately a characteristic Roman feature.

The necessity of accommodating a larger audience during the second half of the fourth century led to the creation of horizontal passageways dividing the auditorium into several sections. We should also note the addition of access ways from the outside to the ends of these passages leading to the upper part of the auditorium (ano parodoi)37. The terms θυρώματα, πρόθυρα, πυλῶνες, and εἴσοδοι were used, without any special distinction, for the doors which monumentalized several of these passages. It is possible that these horizontal and vertical passages were used for division as well as for circulation. Every spectator had a ticket (on clay or ivory). It is my opinion that the image or the letter depicted on the ticket corresponded to a special zone of the auditorium38. We could assume that the central precincts were reserved for certain tribes or associations. Even sculptures were used in this way. In the theatre of Iaitas, for example, a sculpted recumbent lion bordered three rows on the side of each parodos, thus marking a zone for certain citizens39.

At Rhamnous, the statue of a prestigious member of the deme of Rhamnus was placed next to the prohedria40. The statue was an honorific portrait of the donor of the thrones and created a striking visual connection between the donor and the object of dedication. Similarly, at the theatre of Messene, a bronze honorific portrait of the generous agonothetes Sophon was displayed beside the marble throne of prohedria (fig. 4)41. It is absolutely certain that these life-size statues erected on high bases would impede the view to the orchestra and the scene building. And yet, despite this inconvenience, each town chose this prominent place to honor its citizens. This practice was common: while promoting past benefactions, the town was attracting future donors. Another example is the theatre of Acarnanian Stratos, where a large monument placed next to the west throne blocked the view and also the circulation path between the auditorium and the west parodos (fig. 5)42. The monument likely depicted a benefactor or good citizen meant to be emulated.

Sophon beside the marble throne of prohedria (photo by the author).

between the auditorium and the west parodos (Schwandner 2006).

These examples show that as theatres became a more popular building type during the fourth century, they became one of the most prominent display spaces for statues within a Greek town. Obviously this was not a universal development, but rather related to regional peculiarities.

In the second half of the fourth century the theater in Athens echoed the city’s architecture and decoration, its sculptures and paintings, its music and dance. The honorary bronze statue of Astydamas the Younger (340 BC) was erected at the eastern end of the western parodos’s retaining wall. The inscribed statue base indicates that the monument was structurally part of the theatre, rather than an independent monument (fig. 6)43. Accordingly, the statue was set up in a prominent position, as it was visible from almost the whole of the theatre. This unique and certainly expensive position, incorporated into the retaining wall, was unlikely related to the poet’s dramatic victories, although numerous. On the contrary, it should be interpreted as gratitude for Astydamas’s services to the city of Athens. This intention demonstrates the criteria required for having a statue set up in one’s honor. The Athenians placed a statue of Astydamas right in the auditorium of the new “Lycurgan” theatre of Dionysus more than a decade before the statues of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides were erected in the parodos (fig. 7)44.

of its crown and the inscribed pedestral of the statue of Astydamas (Di Napoli 2013).

and the portrait of Menander restored in their original location (Di Napoli 2013).

Similarly, prominent places at the ends of the retaining walls of the cavea were exploited also in the Hellenistic theatres of Delos (fig. 3), Argos, Delphi, and Megalopolis (fig. 8.a and 8.b)45. These statues, portraits of honorable men related to the theatrical production, were viewed by the crowd as they entered the theatre and throughout their time in the auditorium. For this reason, statues were often of a statuary and iconographic type that expressed the subject’s qualities and civic contributions, while contributing to a visually pleasing inner theatre. The prominent position of these statues could impede the view of the events on the orchestra or the proskenion, and furthermore disrupted the view of the audience in the upper auditorium where the wings get wider.

The public at the theatre of Trachones, which could hold at least 2 500 spectators, included two archaistic statues of Dionysus (fig. 9.a and 9.b)46. The two marble statues were comparable in scale, material, and style, and were erected on marble bases attached to the ends of the two retaining walls of the parodoi, one statue at the east parodos and one statue at the west. Archaistic features in pose and dress allude to the archaic statue of Dionysus brought to Athens from Eleutherai. The statues belong to the category of private honorific statues set at the end of the retaining walls, such as we have already mentioned for Delos, Argos, and Delphi. The key difference is that at Trachones this placement reflected the divine nature of the statues. The sacred character of the monument dominated, related to the inherent sacredness of the Rural Dionysia and of dramatic performances in the Attic countryside47. They were definitely not cult statues, but could have served as altars or thymelai where the worshippers could place votive offerings during festivals in honor of Dionysus.

The parodoi/eisodoi

The two long wing entrances, πάροδοι or εἴσοδοι48, were vital to the form and function of the theatral space. First, they reflect the influence of procession on the structure of drama: the entrances were the terminal point of the pompé and through them the audience accessed their seats. Before the procession, while still outside the theatre, the masses of participants shared thoughts and emotions as they prepared themselves mentally for the shared experience inside the theatre. Second, the entrances facilitated fluid action, as the choruses traditionally entered the orchestra through parodoi and connected the performance space with its surrounding environment. During the fourth century, stone theatres were often equipped with a monumental marble propylon and wooden gateways at the parodoi.

East and west parodoi provided access to the Dionysian theatre of Athens49. The east parodos is considered the main entrance as it connected to the monumental Street of Tripods. This part of the theatre held posthumous honorary statues of individuals related to drama. This honor was usually granted after death, thus the public entering from the east parodos could admire the base with portrait statues of the Three Tragedians (Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides) (fig. 7). This monument at the east parodos was part of the Lycurgan program: it illustrates the nostalgic conservatism of his era, as it established a clear link between dramatic production in the fourth century and the golden age of Athenian theatre50. The monument, located just beside the gateway in the Lycurgan in the mid-Augustan period was connected again to the newly-built classicizing Ionic propylon. The fact that the honorary monuments to the Three Tragedians and to Menander were included and thus protected by the Augustan marble propylon reveals the prestige of the east parodos and the monuments set up there. The emphasis given to the main entrances (πάροδοι) with monumental gateways (θυρώματα)51 not only followed the new principles of Hellenistic architecture, but also assured the protection of the theatre’s interior when it was not in use…

Next to the Three Tragedians, the seated portraits of the poets Menander52 and Poseidippos53 offered a “review” of the history of New Comedy by completing the retrospective monuments of the east parodos. According to the decree IG II2 65754, the comic poet Philippides was also honored with a statue along the east parodos of the theatre of Dionysus, beside the great fifth-century tragedians and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. The city thus presented the long and prestigious history of Athenian drama to the public visiting the theatre, both locals and foreigners. However, the west parodos was not left without sculptures: the bases of almost eight monuments have been located55. It is worth noting that the Romans undertook some minor alterations on the monuments of the west parodos, but they left untouched those of the east parodos. This choice testifies to a civilization that respected classical values.

As presented above, honorific portraits are statues of individuals set up in public spaces in return for services. These recipients were civic benefactors, namely citizens who had served their communities as military officers, politicians, statesmen, or generous donors. A study of Hellenistic portraits reveals that the body, gesture, posture, and general attitude of the represented were important and carefully selected. Honorific portraits displayed in prominent places in town wordlessly communicated a message about the honoree. However, to be effective, it was necessary that the public be able to recognize the honored individual and appreciate his service56. The theatre was a fitting context for these acts, as it was very often used as a skene of political life57.

Choregic monuments erected after victories in dramatic contests58 or dithyrambic competitions could be set up outside the theatre, but in its immediate vicinity, at the end of the east parodos and along the Street of Tripods. Choregic monuments were private dedications, by leading citizens proclaiming their importance. The space inside the theatre was reserved for public dedications59. Almost one hundred choregic monuments were placed along the relatively narrow Street of Tripods, seeming to communicate with one another and thus forming a coherent group60. All were on the same side of the road, up on the slope of the Acropolis where the ground was slightly more elevated. In this way, the choregic monuments impressed viewers and could not be overlooked by the citizens of and the visitors to Athens.

The sanctuary of Dionysus and the Street of Tripods were divided into discrete zones, to judge by the kinds of monuments erected there. Before the propylon of the sanctuary of Dionysus and at the beginning of the Street of Tripods, we find choregic monuments of great public importance, such as the monuments for tribal victories; the best and thus the earliest locations to be occupied by votive monuments were surely these in front of the entrance to Dionysus’s sanctuary. Study of the temenos of Dionysus and adjacent areas reveals that the east side of the theatre was covered hundreds of choregic monuments, while the foundations of only five monuments have been discovered at the west one. However, the west must still be considered an equally prominent place for the erection of public and private monuments because of its proximity to the west parodos and the staircases towards the Peripatos. The monument of Nikias, erected southwest of the west parodos, has the form of a temple and is problematic because it is oriented opposite to the audience’s path towards the entrance. The façade of Thrasyllos’s choregic monument was incorporated into the curved line of the Epitheatron’s vertical face, another very prominent position. The Thrasyllos monument61, a façade of three pillars supporting an inscribed architrave and frieze and surmounted by a tripod and a statue of Dionysus, would be very impressive at the top of the auditorium. That choregic monuments – like those of Nikias, and Thrasyllos in 320/319 – were set up in the area of the theatre points to significant changes in the way an individual could impact public space. As stressed by P. Wilson62, it is unlikely that the erection of private monuments in such areas for public display occurred without social and political friction.

Conclusion

In sum, although not a complete review of movement in ancient Greek theatres, this study offers new insights on architectural innovations and traditions, topographical affiliations, and the functions of these public monuments. Furthermore, it reveals political and social contexts over the course of nearly four centuries and offers valuable insights into the ways in which political interactions, obligations of individuals, social groups, and democratic institutions influenced the spatial organization of late Classical and Hellenistic theatres. Of course the theatre, as a public political and cultural space, played a central role. The crowd gathered in a theatre became an audience for religious or dramatic events, or a body of citizens participating at political meetings. The audience members would have known to link the identity of a given honorand with the placement of his honorific statue.

Considering the theatre of Athens as a case study, it seems beyond doubt that the whole zone of the theatre and its extensions had been an area of high circulation for political and cultural events. The decision to transform theatres into stone public buildings inspired the invention of new forms that were more elaborate and could accommodate a larger audience. The new buildings, like their wooden precursors, offered visibility to the orchestra and the stage building, and also to the adjacent shrines, countryside, and landscape. However, as we have seen, some of the statues erected in the theatre area disrupted the physical and symbolic connection of the constituent parts of the theatre. This seeming lack of concern for the fundamental purposes of theatral spaces (perfect sound and an uninterrupted view to the events in the orchestra) was far from a careless accident or oversight, but rather an adaptive use of the space for specific purposes. Venues hosting frequent cultural and political activity, like theatres, were often used for the erection of statues and the choice was highly significant. Statues, as honorific representations located in prominent locations, offer us a glimpse into social hierarchy and how it was shaping public space.

It is evident that Athenians, as well as citizens elsewhere in Greece, firmly appreciated that performance and visual experience were connected, and they cleverly explored the various possibilities of these combined experiences. Divine statues coexisted with portrait statues of poets and of local benefactors. Statues of Hellenistic kings and emperors are almost absent from Greek theatres – the dedication of Philetairos’s statue by his brother Eumenes in the theatre of Delos is an exception – while images of local heroes or individuals with great civic and political careers were privileged and displayed in the orchestra and parodoi. Other places around the theatre were available for private dedications. The best and thus the earliest spots occupied by votive monuments were surely in front of the entrance to Dionysus’s sanctuary. Monumental votives were not set up in the theatre. However, the placement and type of votive offerings and choregic dedications varied spectacularly among theatres. To judge from patterns of display in Classical and Hellenistic theatres, a hierarchical order dictated selection of each location to convey specific messages to the viewer.

After this short review, we conclude that each city with a theatre created its own new formulas to determine how monuments were displayed in its theatral space. Placement of sculpted monuments and related spatial arrangements did not follow a general rule. Thus, display in theatral space was a dynamic and complex phenomenon, claimed and shaped by many different agents, such as individuals and other corporate bodies beyond the demos.

References

- Agelidis, S. (2009): Choregische Weihgeschenke in Griechenland, Bonn.

- Biard, G. (2017): La représentation honorifique dans les cités grecques aux époques classique et hellénistique, BEFAR 376.

- Blum, G. and Plassart, A. (1914): “Orchomène d’Arcadie. Fouilles de 1913. Topographie, architecture, sculpture, menus objets”, BCH, 38, 71-88.

- Brodersen, K., Günther, W. and Schmitt, H. H., dir. (1996): “Historische griechische Inschriften”, in: Übersetzung, II. Spätklassik und Hellenismus (400-250 v. Chr.), Texte zur Forschung 68, Darmstadt.

- Cartledge, P. (1997): “Deep plays’ : Theatre as Process in Greek Civic Life”, in: Easterling, ed. 1997, 3-35.

- Chaniotis, A. (1997): “Theatricality Beyond the Theater. Staging Public Life in the Hellenistic World”, in: Le Guen, dir. 1997, 219-259.

- Chaniotis, A. (2007): “Theatre Rituals”, in: Wilson 2007, 48-66.

- Choremi-Spetsieri, A. (1994): “H οδός των Τριπόδων και τα χορηγικά μνημεία στην αρχαία Aθήνa”, in: Coulson & Palagia 1994, 31-42.

- Connor, W. R. (1989): “City Dionysia and Athenian Democracy”, Classica et Medievalia, 40, 7-32.

- Coulson, W.D.E. and Palagia, O. (1994): The Archaeology of Athens and Attica under the Democracy. Proceedings of an International Conference celebrating 2500 years since the birth of democracy in Greece held at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, December 4-6, 1992, Αθήνα.

- Csapo, E. (2007): “The men who built the theatres: Theatropolai, Theatronai, and Arkhitektones”, in: Wilson 2007, 87-115.

- Csapo, E. and Miller, M. C., ed. (2007): The Origins of Theater in Ancient Greece and Beyond: From Ritual to Drama, Cambridge.

- Csapo, E., Goette, H.-R., Richard Green, J. and Wilson, P., ed. (2014): Greek Theatre in the Fourth Century B.C., De Gruyter.

- Di Napoli, V. (2013): Teatri della Grecia romana: forma, decorazione, funzioni: la provincia d’Acaia, Μελετήματα 67, Αθήνα.

- Di Napoli, V. (2015): “Architecture and Romanization: The Transition to Roman Forms in Greek Theatres of the Augustan Age”, in: Frederiksen et al. 2015, 365-380.

- Dilke, O. A. W. (1948): “The Greek Theatre Cavea”, BSA, 43, 125-192.

- Dillon, S., dir. (2005): Representation of war in ancient Rome, Cambridge.

- Dillon, S. (2006): Greek Portrait Sculpture. Contexts, Subjects, and Style, Cambridge.

- Easterling, P. E., ed. (1997): The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy, Cambridge.

- Fittschen, K. (1992): “Zur Rekonstruktion griechischer Dichterstatuen, 2. Die Statuen des Poseidippos und des Pseudo-Menander”, AM, 107, 229-271.

- Fittschen, K. (1995): “Eine Stadt für Schaulustige und Müßiggänger. Athen im 3. und 2. Jh. v. Chr.”, in: Wörrle & Zanker 1995, 55-77.

- Fraisse, P. and Moretti, J.-C. (2007): Le Théâtre. EAD XLII, Athènes.

- Frederiksen, R. (2000): “Typology of the Greek Theatre Building in Late Classical and Hellenistic Times”, in: Isager & Nielsen 2000, 135-175.

- Frederiksen, R., Gebhard, E. and Sokolicek, A., ed. (2015): The Architecture of the Ancient Greek Theater, Acts of an international conference at the Danish Institute at Athens, 27-30 January 2012, Monographs at the Danish Institute at Athens 17.

- Gebhard, E. (1974): “The Form of the Orchestra in the Early Greek Theater”, Hesperia, 43, 428-440.

- Goette, H. R. (2007): “Choregic monuments and Athenian democracy”, in: Wilson, ed. 2007, 122-149.

- Goette, H. R. (2014): “The Archaeology of the “Rural” Dionysia in Attica”, in: Csapo et al. 2014, 77-106.

- Green, J.R. (1991): “On Seeing and Depicting the Theatre in Classical Athens”, GrRomByzSt, 32, 15-50.

- Griffin, A. (1982): Sikyon, Oxford.

- Gutzwiller, K. (2005): The New Posidippus. A Hellenistic poetry book, Oxford-New York.

- Θέμελης, Π. (2009): “Μεσσηνίας οίνος και Διόνυσος”, Οἶνον ἱστορῶ, ΙΧ, 93-113.

- Haddad, N.A. (1995): Θύρες και παράθυρα στην ελληνιστική και ρωμαϊκή αρχιτεκτονική του ελλαδικού χώρου, Ph. D. Diss. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, School of Architecture.

- Isager, S. and Nielsen, I. (2000): Proceedings of the Danish Institute at Athens 3, Athens.

- Isler, H.-P. (1986): “Grabungen auf dem Monte Iato 1985”, Antike Kunst, 29, 68-78.

- Isler, H.-P. (2007): Das Theater : Grabungen 1997 und 1998. Eretria XVIII, Gollion.

- Klar, L. S. (2005): “The origins of the Roman scaenae frons and the architecture of the triumphal games in the second century B.C.”, in: Dillon, dir. 2005, 162-183.

- Kolb, F. (1989): “Theaterpublikum, Volksversammlung und Gessellschaft in der griechischen Welt”, Dioniso, 59, 345-351.

- Κολώνας, Λ. et al. (2009): Τα αρχαία θέατρα της Αιτωλοακαρνανίας, Αθήνα.

- Κορρές, M. (2009): Αττικής οδοί : αρχαίοι δρόμοι της Αττικής, Αθήνα.

- Κυριακός, K., ed. (2015): Πρακτικά Δ΄ Θεατρολογικού Συνεδρίου, Πάτρα.

- Λαμπάκη, A. (2013): Τα αρχαία ελληνικά θέατρα ως χώρος ίδρυσης γλυπτών και επιγραφών (Statues and inscriptions from ancient Greek theatres), unpublished Ph.D. diss. University of Ioannina, Department of History and Archaeology.

- Λαμπάκη, A. (2015): “Εικόνες Διονύσου και θεατρικός χώρος στα κλασικά και ελληνιστικά θέατρα”, in: Κυριακός, ed. 2015, 71-92.

- Λαμπάκη, A. (forthcoming): “Θεατρικά οικοδομήματα κλασικών και ελληνιστικών χρόνων στην Πελοπόννησο”, in: To Αρχαιολογικό Έργο στην Πελοπόννησο, Τρίπολη, Νοέμβριος 2012.

- Le Guen, B. (1995): “Théâtre et cités à l’époque hellénistique”, REG, 108.1, 59-90.

- Le Guen, B., dir. (1997): De la scène aux gradins, Pallas, 47, Toulouse.

- Long, C. R. (1987): The Twelve Gods of Greece and Rome, Leiden.

- Ma, J. (2013): Statues and cities : honorific portraits and civic identity in the Hellenistic world, Oxford studies in ancient culture and representation 5.

- Meineck, P. (2012): “The Embodied Space: Performance and Visual Cognition at the Fifth Century Athenian Theatre”, New England Classical Journal 39.1, 3-46.

- Millis, B. W. (2014): “Inscribed Public Records of the Dramatic Contests at Athens: IG II2 2318-2323a and IG II2 2325, in: Csapo et al. 2014, 425-446.

- Moretti, J.-C. (1997): “Formes et destinations du proskènion dans les théâtres hellénistiques de Grèce”, Pallas, 47, 1998, 13-39.

- Moretti, J.-C. (2001): Théâtre et société dans la Grèce antique, Paris.

- Moretti, J.-C. (2014): “The Evolution of the Theatre Architecture outside Athens in the Fourth Century”, in: Csapo et al. 2014, 107-137.

- Moretti, J.-C., ed. (2009): Fronts de scène et lieux de culte dans le théâtre antique, Lyon.

- Moretti, J.-C. and Mauduit, C. (2015): “The Greek Vocabulary of the Ancient Greek Theater”, in: Frederiksen

et al. 2015, 119-129. - Μπολέτης, K. (2012): Το χορηγικό μνημείο του Θρασύλλου στην Νότια Κλιτύ της Ακροπόλεως (unpublished Ph.D. diss. University of Ioannina, Department of History and Archaeology).

- Μπολέτης, K. (2016): “Παρατηρήσεις στο ζήτημα της τοποθέτησης του αγάλματος του Διονύσου στο χορηγικό μνημείο του Θρασύλλου”, in: Zάμπας, Κ. et al. (ed.), ΑΡΧΙΤΕΚΤΩΝ, Honorary volume for Professor Manolis Korres, 205-216.

- Μποσνάκης, Δ. and Γκακτσής, Δ. (1996): Αρχαία Θέατρα, Αθήνα.

- Noel, D. (1997): “Les Grandes Dionysies”, Annali di Archeologia e Storia Antica, nuova serie No 4, 69-86.

- Oliver, G. J. (2007): “Space and the visualization of power in the Greek polis: The award of portrait statues in decrees from Athens”, in: Schultz, & von den Hoff, ed. 2007, 181-204.

- Papastamati-von Moock, C. (2007): “Menander und die Tragikergruppe – Neue Forschungen zu den Ehrenmonumenten im Dionysostheater von Athen”, AM, 122, 273-327.

- Papastamati-von Moock, C. (2014): “The Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus in Athens: New Data and Observations on its ‘Lycurgan’ Phase”, in: Csapo et al. 2014, 15-76.

- Πετράκος, B. (1994): “Ανασκαφή Ραμνούντος”, ΠΑΕ, 1994, 1-44.

- Πετράκος, B. (1997): Οι Επιγραφές του Ωρωπού, Αθήνα.

- Πετράκος, B. (1999a): Ο δήμος του Ραμνούντος, Ι. Τοπογραφία, Aθήνα.

- Πετράκος, B. (1999b): Ο δήμος του Ραμνούντος, ΙΙ. Οι Επιγραφές, Αθήνα.

- Polacco, L. (1990): Il Teatro di Dioniso Eleutereo ad Atene. Rome.

- Revermann, M. (2006): “The Competence of Theatre Audiences in Fifth– and Fourth– Century Athens”, JHS, 126, 99-124.

- Rogers, G. M. (1991): The Sacred Identity of Ephesos. Foundation Myths of a Roman City, London/New York.

- Rosso, E. (2009): “Le Message religieux des statues impériales et divines dans les théâtres romains: Approche contextuelle et typologique”, in: Moretti, ed. 2009, 89-126.

- Roux, G. (1990): “Remarques sur l’architecture “dionysiaque” du théâtre grec”, in: Mélanges d’archéologie offerts à A. Audin, Lyon, 213-221.

- Schultz, P. and von den Hoff, R., ed. (2007): Early Hellenistic portraiture: image, style, context: proceedings of a conference held Nov. 9-10, 2002, Athens, Greece, Cambridge.

- Schwandner, E.-L. (2006): “Die Ausgrabung in der antiken Stadt Stratos (Aitoloakarnania) und der Survey des Staatsgebietes ‘Stratike‘”, in: Α΄ Αρχαιολογική Σύνοδο Νότιας και Δυτικής Ελλάδος, Πάτρα 9-12 Ιουνίου 1996, Athens, 531-540.

- Schwingenstein, C. (1977): Die Figurenausstattung des griechischen Theatergebäudes, Münchener archäologische Studien 8, München.

- Sear, F. (2006): Roman Theatres. An Architectural Study. Oxford Monographs in Classical Archaeology, Oxford.

- Smith, R. R. R. (1988): Hellenistic Royal Portraits, Oxford.

- Sokolicek, A. (2015): “Form and Function of the Earliest Greek Theatres”, in: Frederiksen et al. 2015, 97-104.

- Σταϊνχάουερ, Γ. (1979): “Αρχαιότητες και μνημεία Λακωνίας-Αρκαδίας”, ΑΔ 29, Β2, Χρον. [1973-1974], 283-301.

- Steinhart, M. (2007): “From Ritual to Narrative”, in: Csapo & Miller, ed. 2007, 196-220.

- Stewart, A. (2005): “Posidippus and the truth in sculpture”, in: Gutzwiller 2005, 183-205.

- Τζάχου-Αλεξανδρή, A. (2007): “Αρχαϊστικά αγάλματα Διονύσου από το θέατρο του Ευωνύμου”, AE, 146, 1-42.

- Vollgraff, W. (1951): “Le théâtre d’Argos”, Mnemosyne 4 ser. IV, I.

- Wilson, P. (2000): The Athenian Institution of Khoregia: The Chorus, the City and the Stage, Cambridge.

- Wilson, P. (2007): The Greek theatre and festivals. Documentary Studies, Oxford.

- Wilson, P. (2015): “The festival of Dionysos in Ikarion. A New Study of IG I3 254”, Hesperia 84, 2015, 97-147.

- Wörrle, M. and Zanker, P. (1995): Stadtbild und Bürgerbild im Hellenismus: Kolloquium, München, 24. bis 26. Juni 1993, München.

Notes

- This article was submitted in July 2017 therefore recent bibliography is not included.

- All recent bibliography in: Di Napoli 2013; Csapo et al. 2014; Frederiksen et al. 2015.

- I refer here to the debate about the circular or trapezoidal shape of the orchestra, the temporary character of ἴκρια, the movement from the orchestra of the Agora to the slope of the Acropolis, etc. See, Gebhard 1974; Sokolicek 2015, and the thematic bibliography in: Frederiksen et al. 2015, 448-459.

- For an alternative approach, see Meineck 2012. See also Oliver 2007.

- This material was collected and studied by the author for my PhD dissertation, Λαμπάκη 2013.

- Di Napoli 2013.

- Ma 2013, 91.

- For the transition to the Roman Imperial period, see Di Napoli 2015.

- Frederiksen 2000; Moretti 2014. For the vocabulary used by ancient Greeks to describe their theatral architecture and other terms that are retained in modern nomenclature, see Moretti & Mauduit 2015.

- Also Moretti 2014.

- Schwingenstein 1977. Ma 2013. Smith 1988, 16: “In the Hellenistic polis, an eikon of almost anyone might be set up, but what mattered was who set it up and where.”

- See below.

- At the theatres of Magnesia on Maeander, Priene and Ephesos.

- See below

- Gerkan 1921, 47-48. By contrast, throughout the Roman period the scaenae frontes were widely used for elaborate sculptural programmes, see Rosso 2009.

- For the use of Sikyon’s theatre for political meetings, see: Poll. 29.25.2. Plutarch, Aratus 8. Griffin 1982, 16.

- Roux 1990. Steinhart 2007.

- Green 1991.

- Moretti 1997, 37 believes that performances took place mainly in the orchestra. Moretti 2001, 183 presumes that in Western Greece performances occurred on a raised proskenion, in contrast to the situation on mainland Greece.

- Kolb 1989. The prohedria is clearly identified in many theatres as part of the koilon, but often at the same time as a separate section. For the predecessors of elaborated stone prohedria see, Dilke 1948, 165: “The fine carving and architectural ornamentation found even in the earlier stone Prohedriae justifies the assumption that their predecessors were in wood.”

- For ceremonial entrances in theatres, see Chaniotis 2007, 59-62.

- For all similar epigraphic sources, see Csapo 2007, 110 n. 48.

- For Delos, see Fraisse & Moretti 2007, 171f. For Messene, see Θέμελης 2009, 96, fig. 5. For Stratos, see Μποσνάκης & Γκακτσής 1996, 114-115; Frederiksen 2000, 147. For Arcadian Orchomenus, see Σταϊνχάουερ 1979, 301; Blum & Plassart 1914, 80. For an overview of independent marble thrones, see Λαμπάκη 2013, vol. 2, ch. I.2.

- Πετράκος 1997, n° 439.

- Supra n. 21.

- Paus. 2.20.7. Herodotus, 1.82.

- Klar 2005; Di Napoli 2013.

- Polacco 1990, Appendice 29-32.

- Connor 1989; Cartledge 1997; Noel 1997, 83.

- For the different depictions of Dionysus’ xoanon, see Demosthenes, Against Meidias, 10. In: Euripides’ Antiope, TrGF 203. Athenaeus, 12.533C. Aristophanes, Acharnians 243 a, ed. N. G. Wilson, 42-43.

- For example, the statue of Philipos II from Aigai. Diodorus, XVI, 91-94. Images of mortals and local heroes were brought in procession during the festivals organized by Ptolemy II Philadelphus & Antiochus IV Epiphanes, see Long 1987, 224-225, 248; IG XII 2 527 (1). Vibius Salutaris, in: A.D. 103/4 donated to Artemis and the city of Ephesus 29 gold and silver portable images to be displayed in the theatre and brought in procession; see Rogers 1991, 80-115, 156-157. At Alexandria, the koinon of Dionysiac Technitai carried in pompe the statue of Dionysus, together with the statues of silens, satyri and personifications, like Tragedy, Horai, etc. Athenaeus, V, 27, 198 etc. Le Guen 1995, 85f.

- Revermann 2006.

- Wilson 2015.

- Πετράκος 1999a.

- Frederiksen 2000, 140-141.

- Sear 2006, 413, plan 434, pls 142-3 (with bibliography).

- Moretti 2014, 117f.

- Λαμπάκη 2013, vol. 2, 240f.

- Isler 1986, 68-70, and mostly fig. 7.

- Πετράκος 1994, 13, no. 2 and 3. Πετράκος 1999b, 94 n° 112.

- Θέμελης 2009, 96-97, πίν. 25β.

- Schwandner 2006, 535: “ein großes Anathem”. Κολώνας et al. 2009, 151.

- Papastamati-von Moock 2014, 23f: the author has shown that the Astydamas monument was incorporated into the stone theatre at the time of the latter’s construction, soon after 340.

- Diog. Laert. 2, 43 = Heraclides F 169 Wehli.

- Λαμπάκη 2013, vol. 2, 233f. For Argos and Megalopolis, see Λαμπάκη forthcoming.

- Τζάχου-Αλεξανδρή 2007. For images of Dionysus in ancient Greek theatres, see Λαμπάκη 2015.

- Goette 2014.

- For the application of these terms, see Moretti & Mauduit 2015, 121.

- Thanks to the work of Manolis Korres (Κορρές 2009, 74-82 with models of the theatre and successive architectural phases) on ancient roads, we are able to situate the sanctuary of Dionysus and the first theatrical installation within the pre-existing road network on the south side of the Acropolis.

- Papastamati & von Moock 2014.

- Haddad 1995.

- Papastamati & von Moock 2007.

- Fittschen 1992, 229-271; Fittschen 1995, 67-68, fig. 29; Stewart 2005, 183-205; Dillon 2006, 102.

- Brodersen et al. 1996, 105-107, n° 308.

- Pausanias informs us that other tragic and comic poets were honored as well in the theatre, but apart from Menander these were not well known (Paus. 1.21.1). IG II2 648 (295/4) mentions a foreigner who was to be honored with a bronze statue in the theatre.

- Very recently, Biard 2017.

- Chaniotis 1997.

- Monuments with inscribed public records of dramatic contests were erected within or near the precinct of Dionysus completing the sequence of honorific decrees and public monuments erected in the area. Major sources for dramatic choregoi include the inscribed public record IG II2 2318. Inscribed choregic monuments, primarily the tripod monuments, supplement the information from the inscription about who was performing choregia and when. For details, see Millis 2014.

- Choregic monuments were usually erected along the festival road and the parodos leading from the sanctuary of Dionysus to the theatre; for the west parodos at Eretria’s theatre, see Isler 2007.

- All bibliography in: Chοremi & Spetsieri 1994.

- Μπολέτης (2012) & Μπολέτης (2016).

- Wilson 2000, 225-227.