When William Shakespeare began writing his plays the word rogue was still a comparatively recent addition to the English language. It had begun as a term used as slang by the criminal classes, and Shakespeare, along with others, obviously liked it. He used it in twenty-two of his plays. Other writers, including John Awdeley, Thomas Harman and Shakespeare’s rival Robert Greene, built a whole literary genre out of exploring roguery. It was a very widespread subject for popular literature. Those three writers, along with a number of others, wrote a succession of what were, for the time, very successful volumes on the subject of rogues. At a time when around twenty-two percent of published books reached a second edition within twenty years,1 the first part of Greene’s work made two editions in the first year (1591), and a third the year after.

To this must be added the large number of broadsheet ballads and other more ephemeral publications, numbering in the Elizabethan period in the thousands, usually anonymous, in which rogues were not merely commemorated but even celebrated. But in Shakespeare’s plays the word is applied to many different characters, in a variety of ways, and is furthermore applied by a diverse range of characters too. To offer but a few examples, Coriolanus hurls it at the mob of rioting Roman citizens:

What’s the matter, you dissentious rogues

That, rubbing the poor itch of your opinion

Make yourselves scabs? (I, 1, 174-176).2

Hamlet uses it on himself: “Oh what a rogue and peasant slave am I” (II, 2, 577).3 In Othello Emilia, as she realises the enormity of his deceptions, applies it to her husband Iago:

I will be hang’d, if some eternal villain,

Some busy and insinuating rogue,

Some cogging, cozening slave, to get some office,

Have not devised this slander; I’ll be hang’d else. (IV, 2, 153-156)4

Timon of Athens finds the word so evocative that he uses it three times in the same line:

Rogue, rogue, rogue

I am sick of this false world, and will love nought

But even the mere necessities upon ‘t. (IV, 3, 418-420).5

But by far the most frequent uses of the word by Shakespeare are in the two parts of Henry IV, Henry V and the Merry Wives of Windsor. The use of the word in relation to one particular character outnumbers any competitor by a considerable distance. That man is Sir John Falstaff. In one way this is not surprising. The term is drawn from the tribal language of the criminal class, and Falstaff and his gang are the most closely depicted group of criminals in all of Shakespeare’s writings. In their headquarters at the Boar’s Head in Eastcheap they discuss and plan their crimes, and return to divide their spoils, if any. The use of the term is part of the depiction of that criminal world. As well as being applied to Falstaff himself, it is also applied, in the next play, Henry V, to one of the members of his gang, Pistol, after his death. It is only one of the terms used by or about this fraternity, but it is used more frequently than others, and the usage of the word in this context has come to have an effect upon the overall meaning of the word in English ever since.

Rogue is a word which had a further relevance to Shakespeare’s profession. The 1572 Vagabonds Act, which held force in the early years of Shakespeare’s career, specifically classed “common players of interludes” along with “rogues and vagabonds”, and allowed for draconian punishments including that they be “grievously whipped and burned through the gristle of the right ear with a hot iron of the compass of an inch about”. This applied to those players who were not touring under the protection of a lord, or who had not been licensed by two Justices of the Peace, but while Justices or magistrates would confidently be expected to be literate, it could by no means be guaranteed that all of those constables around the country entrusted with law enforcement could read, so such documentation was not necessarily always a failsafe guarantee. To the Puritans, who were a rising force in Shakespeare’s England, particularly as the Sixteenth turned to the Seventeenth Century, the players were instruments of corruption, and the opinion of a nobleman, or his request that his servants be allowed to travel without hinderance, while grudgingly complied with, made no difference to their beliefs. Although some towns might actually declare holiday when the players arrived in their vicinity, there are also numerous recorded cases of towns paying the players to go away rather than play within their boundaries.6 Although the Act of 1597 modified the extremity of the sanctions, the opinion of players in many circles remained unflattering. Shakespeare might be expected to have a degree of sympathy with rogues and vagabonds because in the eyes of certain sections of society he would have been considered to be one.

Shakespeare’s characters’ use of the term often reveals something of the nature of the speaker as well as of the subject, not least because some of those to whom the term might most appropriately be applied are among the most profligate in using it when speaking of others. Parrolles, for example, in All’s Well That Ends Well (IV, 3, 142, 164 and 167)7 uses the term on three occasions to describe others, in the process of proving to the satisfaction of Bertram (IV, 3, 236) that he, Parrolles, is undoubtedly a rogue himself. An even more vivid example of this is Autolycus, in The Winter’s Tale. Ever since the 1709 edition of Shakespeare’s plays, edited by Nicholas Rowe and published by Jacob Tonson, the names and some identifying descriptions of the characters have been listed at the beginning of each play. In this, and subsequent editions, for readers Autolycus is described in the Dramatis Personae, before the play even starts, as a rogue. In his scene with the Clown (in Shakespeare’s time a term more widely used to describe a country bumpkin than an entertainer), in Act IV, Scene 3, he invokes the name of rogue several times to describe his supposed attacker, while he masquerades as the victim of a robbery by a fictitious version of himself. His subterfuge works. The Clown knows of the rogue Autolycus: “Not a more cowardly rogue in all Bohemia” (IV, 3, 110).8 As the Clown assists a stranger he believes to be a victim, Autolycus is quietly stealing his money. Autolycus embraces the title of rogue without a qualm. In the next scene he says: “let him call me rogue for being so far officious; for I am proof against that title and what shame else belongs to’t” (IV, 4, 972-974). Real rogues are unrepentant.

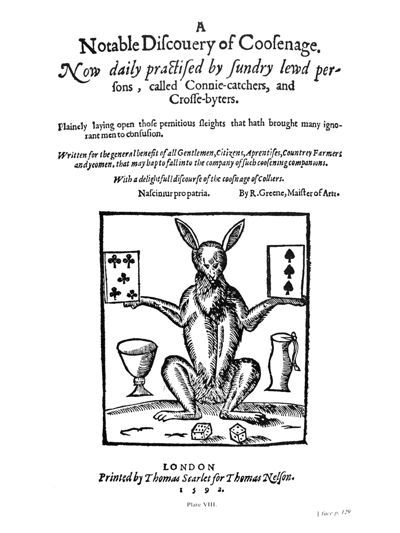

Rogues in Shakespeare’s England were expected to display certain characteristics. As outlined above, there was a body of literature on the subject. The earliest tract, John Awdeley’s Fraternitie of Vacabonds, probably came out around 1560, and was followed a few years later by Thomas Harman’s Caveat, or Warning for Common Cursetors, vulgarly called Vagabonds (1567)9. Both were popular, and reprinted a number of times. They delineated the various types and categories of rogues and vagabonds, and defined a large number of words of their particular slang, or “cant”. There were other writers who contributed to the genre, the best known today being the aforementioned Robert Greene, who wrote three volumes on the subject of “cony-catching”, to use a term which applied by the criminal fraternities to the separating of the gullible from their money. Coney is a slang word for a big fat rabbit, and the “Coney Catchers” were Elizabethan con-men, who preyed particularly upon tourists and country folk who came to the big city. These Coney Catchers were certainly a rich subject for a writer of sensationalist booklets. Three volumes followed each other in quick succession describing the various confidence games and tricks employed by these denizens of the underworld. Greene was the perfect author for such a series. He was well placed to observe that underworld, living in the midst of it. His common-law wife was the sister of a notorious highwayman, Cutting Ball, who was eventually hanged for his crimes, more than likely commemorated in broadsheets at that time.

One of the main locations for such activities in London was in the area around St Paul’s. The Cathedral was the centre of many aspects of London life. Paul’s Yard was the centre of the bookselling trade, and Paul’s Cross, the open air pulpit outside the cathedral, became after the Reformation, a major forum for radical Evangelical preaching, with often as many as 5,000 auditors attending for a particularly well-known speaker. As for the church itself, although the spire had been destroyed by fire following a lightning strike in 1561, Paul’s was still a centre for pilgrimage, to the tomb of St Erkenwald, even after the Reformation. Although the church, originally one of the very finest in Christendom, had deteriorated considerably, it was still one of the sights of London which visitors from elsewhere would be expected to make a point of visiting. The Cathedral had one of the longest naves in Europe, so long that it was colloquially referred to as “Paul’s Walk”. This was where Londoners came, to transact business, to buy and sell and, most of all, to hear the news and gossip. Coal carts might take short cuts through the aisles, and drunks and derelicts sleep in the pews. Milman quotes Bishop Braybrooke, who issued an open letter in which he not only decries these abuses of the House of God, but also that:

others […] by the instigation of the Devil [using] stones and arrows to bring down the birds, jackdaws and pigeons which nestle in the walls and crevices of the building. Others play at ball […] breaking the beautiful and costly painted windows to the amazement of spectators.10

Clearly it was a setting in which the atmosphere was hardly one of sanctity, and just as happens in the present day, wherever tourists, either foreign or from the countryside, congregated, there too rogues, coney-catchers, would be likely to gather to relieve them of the burden of carrying a heavy purse. There were rogues of all sorts and both sexes in evidence around St Paul’s.

Indeed there were many divisions and subdivisions of rogues and vagabonds. Real roguery was a complicated and hierarchical business. The earlier writers actually listed and described a wide variety of categorisations. Harman expounds upon the different classes of vagabonds at greater length than Awdeley, and devotes separate chapters to two types of rogues, the ordinary variety and what both writers call “Wild Rogues”.11 Rogues are seen, in this context, as a subdivision of vagabonds, which is a more all-encompassing term. But rogues and “Wild Rogues”12 appear in the list of degrees of idle vagabonds at numbers 4 and 5 respectively, coming after “Rufflers”, “Uprightmen” and “Hookers or Angler”s but ahead of “Priggers of Prancers”, “Palliards” and “Fraters”. Female Vagabonds have their own categories, including such terms as “Bawdie Basket” or “Kinchin Mort”. Although carefully differentiated, a number of these categories shared common traits. Rogues usually pretend to be something they are not, in order to lull their victims into a false sense of security so that they can more easily be robbed or conned into parting with their belongings. In this sense the behaviour of Autolycus in the scene referred to in Winter’s Tale is a revealing example. To behave as a rogue suggests deception, pretence and often disguise, and all are used in order to steal. The attachment of “fencers, bearwards, common players of interludes and minstrels”13 to the 1572 version of the Vagabonds Act might seem harsh from a modern perspective, but to the vociferous and increasingly influential Puritans actors used exactly the same tricks, those of deception, pretence and disguise, in order to cozen audiences out of their hard-earned wages, perhaps even to steal their souls away from the contemplation of salvation. Actors were therefore clearly rogues in their world view, and their inclusion under the Act’s provisions entirely appropriate.

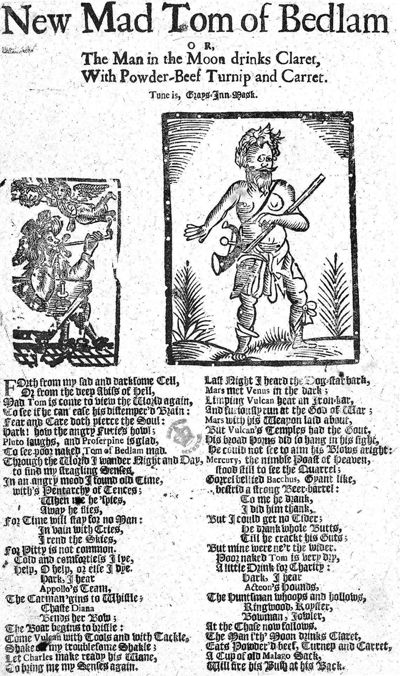

There are other categories from Harman’s list to be found in Shakespeare. When Edgar assumes to role of Tom of Bedlam in King Lear14 he adopts the category of an “Abraham Man”, who “walketh bare armed and bare legged, and fayneth himself mad… and nameth himself Poor Tom”.15 An “Abraham Man” would usually claim to have been released from the Bethlehem Hospital, just outside Bishopsgate in London, commonly known as Bedlam. This was where psychiatric patients or, as the Londoners of the time called them “lunatics” (sic) were confined in Elizabethan London, although it is conjectured, given that “Abraham Men could be found all over England, that many of those who claimed to be so had never been anywhere near that specific hospital. Shakespeare was working, whether his audiences knew it or not, very precisely within Harman’s definition of the characteristics of an “Abraham Man” when he drew Edgar as “Mad Tom”.

Tom o’ Bedlam has a long pedigree in England. He features in the eponymous poem which Harold Bloom describes in an interview as: “The greatest anonymous poem in the language”.16 Bloom actually goes so far as to say that “I can’t think that anyone but Shakespeare could have written it”, although his opinion in this respect is unique. He opines that it was written around 1600, making it a little older than King Lear, but it is also considered by some to be part of an older tradition than that. It lays out both the internal and the external life of Tom o’ Bedlam:

From the hag and hungry goblins

That into rags would rend ye,

The spirit that stands by the naked man

In the Book of Moons defend ye,

That of your five sound senses

You never be forsaken

Nor wander from your selves with Tom

Abroad to beg your bacon17 (1-8)

But the most famous and evocative stanza comes later:

With a host of furious fancies

Whereof I am commander

With a burning spear and a horse of air,

To the wilderness I wander

By a knight of ghosts and shadows

I summoned am to tourney

Ten leagues beyond the wide world’s end:

Methinks it is no journey. (85-92)

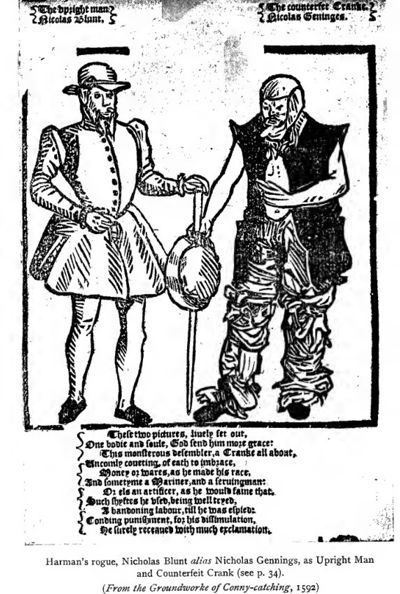

The “Abraham Man” ranks below ordinary rogues and vagabonds in the pecking order, but then rogues do not sit at the top of the hierarchy. First the “Ruffler”, then the “Uprightman stand higher in that particular pyramid, and rogues rank below both of them. According to Harman, “A Ruffler goeth with a weapon to seek seruice, saying he he hath bene a seruitor in the wars, and beggeth for his reliefe, but his chiefest trade is to robbe poore wayfaring men and market women”.18 For him violence, or the threat of violence, is part of his trade. He commands fear, not only from his victims but also from the other vagabonds. So too does “An Vpright Man” (sic). He is described as

one that goeth with the trunchion of a staffe […]. This man is of so much authority that meeting with any of his profession, he may cal them to accompt, & commaund a share or snap vnto himself, of al that they haue gained by their trade in one month […]. And if he doo them wrong, they haue no remedy against him no though he beat them, as he vseth commonly to do. He may also commaund any of their women, which they call Doxies, to serve his turn.19

© British Museum, 95, b. 19.

It begins to be obvious why it might have been a relief to meet an ordinary “rogue” rather than either of these two more pugnacious types.

“A roge is neither so stoute or hardy as the vpright man”.20 Harman’s description is enlivened by a lengthy example of two typical rogues, and their robbing of a parson. Rogues generally use their wits rather than their strength to get what they want. The term Greene uses for their activities, “coney-catching”, which portrays the victims as fat rabbits destined for the cooking pot, primarily describes the fleecing of the gullible rather than the use of violence, although violence does occasionally figure in necessity. In the scene in Winter’s Tale, with Autolycus and the Clown, the rogue Autolycus does refer to the supposed beating he has received less than totally reprehensible, as a victim.

It is also the case, in Shakespeare, that the term “rogue” is applied more commonly, although not exclusively, to social inferiors. A servant is often subject to being referred to as a rogue. In The Taming of the Shrew, for example, Lucentio refers to the young servant Biondello as a rogue (I, 1, 227), and Petruchio shouts at his servants calling them rogues in (IV, 1, 139 and 142).21 In Love’s Labours Lost, Biron applies the word to the Boy (V, 2, 175 and 181).22 Cleopatra uses it before drawing a knife on the messenger who brings her news that Antony is married (II, 5, 92).23

In the hierarchy of insult, the term rogue is not as bad as some. As seen above, Autolycus actually embraces the term. For Shakespeare, “rogue” is not as bad as “villain”. When Tybalt calls Romeo a “villain” (III, 1, 62)24, he expects Romeo to be so insulted that he will draw his sword and fight to the death. “Villain” is a much more common epithet in Shakespeare, used nearly three times as often. A “rascal” is worse than a rogue, although used slightly less often. “Varlet”, by Shakespeare’s time already a rather old-fashioned term of abuse, was worse than rogue. So within the term “rogue” there are clearly some elements which make rogues less than totally reprehensible. Some rogues may even, under the right circumstances, be capable of evoking a degree of sympathy. As suggested above, rogues use their wits rather than force. Rogues are often the underdog. Their crimes are seldom fatal, although as noted in Othello, Emilia refers to Iago as a rogue, and his crime results in death. But more often than not the rogue’s crimes are quite petty. Rogues can be entertaining in their wickedness, whereas with villains this is not the case. While admiring a rogue may be going too far, a rogue can be applauded for the skill with which the scheme is carried out. In this respect Autolycus, the self-identified rogue, displays all of the characteristics. But of all the rogues who appear in Shakespeare’s plays, there is one who not only epitomises all of the requisite traits of a rogue, but in his bravura fulfilment of that role redefined the word for future generations. That rogue is Sir John Falstaff.

Falstaff appears in both parts of Henry IV, is referred to in Henry V, and is the central figure in The Merry Wives of Windsor. He is one of the most recognisable characters in all of English drama, and is a comic creation that can genuinely be ranked alongside Hamlet, King Lear and the other great figures in Shakespeare’s canon. He is one of the most multi-facetted characters Shakespeare created, being both comic and ultimately tragic. Falstaff was so popular that, whether or not one believes the myth that Queen Elizabeth herself demanded another play to see Falstaff in love, there was certainly a demand from the members of Shakespeare’s audience to revive him for The Merry Wives of Windsor. Falstaff is a knight. He is not an aristocrat, he has little status in the outside world. He associates deliberately with those who afford him status, so he has status compared to those around him for much of the play. He has some education, quoting Galen in Henry IV, Part 2 (I, 2, 120).25 He has surrounded himself with a group of followers, and he has been fortunate to find a safe haven in which to base himself. He has neither money nor lands, and his credit has run out. He has very few options to acquire money. The idea of working is unthinkable, so he has turned to a life of crime. He and his gang rob travellers. He might aspire to being a “Ruffler”, if he were any good at it, but for the audience he is redeemed by the obvious fact that he is a hopeless robber. But to Falstaff this is a romantic profession. “Why, Hal, ‘tis my vocation, Hal: ‘tis no sin for a man to labour in his vocation” (I, 2, 211)26. He has already asked Hal to change the designation of purse-takers:

Marry, sweet wag, when thou art king, let not us that are squires of the night’s body be called thieves of the day’s beauty: let us be Diana’s foresters, gentlemen of the shade, minions of the moon; and let men say we are men of good government, being governed, as the sea is, by our noble and chaste mistress the moon, under whose countenance we steal. (I, 2, 134-140)

Falstaff is a liar. His lies are huge, and obvious. Part of his saving grace is that almost no one believes him. There is an English truism that there are two kinds of ability to lie: the first is the ability to lie so as to convince others, the second is the ability to lie so as to convince yourself. Unfortunately Falstaff is possessed solely of the latter of these two abilities. He lies to everyone, friends, enemies, his followers, officials, indeed to everyone except the audience. He confides truthfully in the spectators. He shares this trait with Autolycus, but although this underlines his roguery, this habit is not unique to rogues. Richard III does the same, although he is the first to tell the audience that he is that far worse thing, a villain (I, 1, 30).27 What is more, even Prince Hal, the heir to the throne does so too. His address to the audience explains exactly how and why he is dissembling. But whereas Falstaff confiding in the audience creates empathy, Hal doing the same has a different effect. Hal speaks directly to the audience, telling them, in reference to his companions, that he is only pretending to go along with “the unyoked humour of your idleness” (I, 2, 202 et seq.). Given that Hal’s journey over three plays, from dissolute youth to the hero of Agincourt, needs a starting point, the distrust he engenders in the audience through this speech is gradually redeemed, in the first play by his bravery in battle and his loyalty to his father, in the second play by his rejection of Falstaff and in Henry V by his trust in God leading, as he states, to his overwhelming victory against all odds at Agincourt. Falstaff confiding in the audience makes them co-conspirators in his schemes.

Falstaff’s belief system is a selfish one. His wonderful speech before the battle of Shrewsbury sets out his views on honour:

can honour set a leg? no: or an arm? no: or take away the grief of a wound? no. Honour hath no skill in surgery, then? no. What is honour? A word. What is in that word honour? What is that honour? Air. A trim reckoning! Who hath it? He that died o’ Wednesday. Doth he feel it? no. Doth he hear it? no. ‘Tis insensible, then. Yea, to the dead. But will it not live with the living? no. Why? Detraction will not suffer it. Therefore I’ll none of it. Honour is a mere scutcheon: and so ends my catechism. (V, 1, 128 et seq.)

This outlines his philosophy, but he has a classic set of roguish actions before the end of the play. In the concluding moments of the battle (V, 4, 113 et seq.), he rises up from having pretended to be dead, finds Hotspur’s body, and tells the audience how he is going to claim to have killed the Percy. In this one scene, he encapsulates many of the traits of Shakespearean roguery. He uses a position of supposed weakness, having pretended to be a corpse in order to escape death. When everyone else has gone he rises up, but immediately sees a chance to lie for profit, using the opportunity to steal potential reward due to another, and to do so as brazenly as possible. If he were to succeed, the audience might resent him, but the fact that he fails, but continues to lie unashamedly even when his lies are revealed is part of his attraction for audiences. Falstaff is a rogue, but he is the most attractive character in the play, because although he is a liar and a scoundrel, as far as the audience is concerned, he confides truthfully in them.

In the Second Part of Henry IV, while Falstaff continues as a rogue, with his lying and deception, he has been telling stories to Shallow, conning money out of him against a set of wildly optimistic expectations. He has also been siphoning off the money he has been given to raise a regiment. Firstly, he has spent the money, then secondly he allows any men who can afford to do so to bribe him to avoid military service. When Shallow expresses surprise, as “They are your likeliest men” (II, 2, 264), Falstaff justifies recruiting one of the skinniest and most feeble men he sees, Shadow, by saying “give me this man. He presents no mark to the enemy.- the foeman may with as great aim level at the edge of a penknife” (III, 2, 274-276). In this he is his old cynical and unrepentant roguish self. But as the play progresses, his function gradually moves from the comic towards the tragic. His rejection by the Prince when he becomes King is devastating. But in this moment the new King Henry V demonstrates how he has both learned from and rejected the lessons in dissimulation that he acquired from Falstaff and his companions. It is an important step on his journey towards redemption. But there can be no redemption for Falstaff. It is not in his nature to repent. The last the audience sees of him is that he and his band are being led off to the Fleet prison. The Epilogue promises more Falstaff in the next play, but that never materialises. He is an unseen presence in Henry V, where his illness and death are ascribed by Mistress Quickly to Hal’s betrayal. The old rogue, who has lived by his wits in the conning of others comes up against a much darker, deeper and more political dissimulation, and when he is forced to accept that Hal has turned his back on him it has “killed his heart” (II, 1, 86).

In fact Falstaff does reappear again, but the Falstaff to be found in The Merry Wives of Windsor is a diminished figure from the colossus of the Henry plays. Instead of a medieval figure who consorts with royalty, he has far more in common with a member of the Elizabethan bourgeoisie. There is absolutely no evidence to support the persistent rumour that Shakespeare wrote the play in two weeks at the request of Queen Elizabeth to see Falstaff in love, but to attempt a spin-off for a favourite character is often risky, when that character is removed from the context in which he or she flourished. It is impossible to argue that Merry Wives is amongst Shakespeare’s best plays, but there is still great theatrical vitality in the piece, and even a diminished Falstaff is worth watching, and the play has its supporters. Indeed Catherine the Great of Russia made an adapted translation of the play (1786). And Frederich Engels said, in a letter to Karl Marx (1873), that “There is more life and reality in the first act of the Merry Wives alone than in all of German literature”.28

In Merry Wives we do not see Falstaff actually in love. We see the old rogue attempting to woo the wives of two burghers of Windsor at the same time, his motives being primarily mercenary, although with some lust thrown in. In their pursuit he lies and cheats, and at the same time is trying to cheat someone who is actually the disguised husband of one of the ladies, who is in turn trying to trick him. Falstaff fails again and again. In the course of his failures he is thrown into a muddy ditch, having hidden amidst the dirty laundry, he is beaten and chased while disguised as a woman, and eventually the whole community unites to humiliate him by luring him at night time to Herne’s Oak in the park and tormenting him dressed as goblins. This is not the usual sort of comedy associated with Shakespeare. Certainly Shakespeare never wrote another play of this type. But if Falstaff is missing some of the traits that gave him stature in the other plays, those that remain are the elements of the rogue. In fact this middle class comedy is all about roguery of one kind or another. What the play eventually shows is that the old world, in which Falstaff could be a pre-eminent rogue, is gone, to be replaced by roguery of a newer kind, the roguery of the emergent bourgeoisie. This is partly why the play was so highly regarded by the Marxists, who saw within Merry Wives, amongst other plays, a clear example of the progress of history, where the emergent bourgeoisie were, in their own time, the progressive class which swept away the old vestiges of feudalism.29

But such has been the success of Falstaff as a literary and dramatic icon that the sort of roguery he displays has coloured the way the word is used in succeeding generations. Falstaff made roguery on stage fun. He was far from being the first to do so, his roots go back to Ancient Greece, he has elements of the Miles Gloriosus from Roman Comedy, the Capitano from Commedia dell’Arte, the Vice figure from medieval English morality plays, but Falstaff is the one who lives on, the one whose roguery was enjoyed by the Queen of England, the Empress of Russia and the founders of Communism. His influence has spread far and wide. He is often among the foremost Shakespearean characters to be adapted into other media, from opera (Falstaff, Verdi, 1893) to comics (Kill Shakespeare, Anthony Del Col and Connor McCreery, 2010) to Kyogen (The Braggart Samurai, Hora Zamurai, 1991). The first Shakespeare play to be filmed in the Communist world was Die Lustigen Weiber von Windsor (1950), the 9th most successful film ever produced in East Germany. Many writers since have created characters who stand upon Falstaff’s enormous shoulders. But he leaves a legacy too in the language. Nowadays in English “rogue” is used often as a deliberately archaic word, to suggest someone who is doing things that are wrong, but not seriously wrong, someone who lies and cheats but does little lasting harm. A rogue might sell fake handbags rather than rob a bank. It is also used, in an echo of Merry Wives, as a term for a man (definitely not used of a woman) who spends the night at a cocktail party flirting, usually unsuccessfully, with other people’s wives. Almost all of the earlier meanings of the word “rogue” have disappeared from modern usage, but it remains in use, largely in the ways in which Shakespeare has portrayed roguery through the person of his greatest comic creation, Sir John Falstaff.

Notes

- Alan B. Farmer and Zachary Lesser, “What is Print Popularity? A Map of the Elizabethan Book Trade”, in Andy Kesson and E. Smith (eds), The Elizabethan Top Ten: Defining Print Popularity in Early Modern England, ebook edition, London, Routledge, 2016, loc. 842.

- W. Shakespeare, Coriolanus, Entire Play, Folger Shakespeare Library, available Shakespeare.folger.edu [FSL].

- W. Shakespeare, Hamlet, Entire Play, FSL.

- W. Shakespeare, Othello, Entire Play, FSL.

- W. Shakespeare, Timon of Athens, Entire Play, FSL.

- For example, Alwin Thaler, “The Travelling Players in Shakespeare’s England”, Modern Philology, vol. XVII, 9, January 1920, p. 121-146, p. 129.

- W. Shakespeare, All’s Well That Ends Well, Entire Play, FSL.

- W. Shakespeare, The Winter’s Tale, Entire Play, FSL.

- Most of this material, with engravings, is now available on line thanks to the Gutenberg project.

- Henry HartMilman, Annals of St Paul’s Cathedral, London, Murray, 1868, p. 83-84.

- Thomas Harman, A Caveat or Warning for Common Cursitors Vulgarly Called Vagabonds, Edward Viles and F.J. Furnivall (eds), The Rogues and Vagabonds of Shakespeare’s Youth: Awdeley’s ‘Fraternitye of Vacabondes’ and Harman’s ‘Caveat’, 1st Edition online, London, Chatto and Windus, 1907.

- The difference between the two is that “A Wilde Roge is he that is borne a Roge: he is more sobtil and more geuen by nature to all kinde of knauery then the other”, ibid, loc. 1498.

- An Act for the Punishment of Vagabonds, and for the Relief of the Poor and Impotent, Catalogue Number HL/PO/PU/1/1572/14Eliz1n5, Parliamentary Archives, https://www.parliament.uk.

- W. Shakespeare, King Lear, Entire Play, FSL (I, 3, 1-210; III, 4, 50 et seq.; III, 6, 6 et seq.; IV, 1, 27 et seq.; IV, 5, 2 et seq.).

- John Awdeley, A Fraternity of Vagabonds, dans The Rogues and Vagabonds…, loc. 872.

- “Harold Bloom on Harry Potter, the Internet and more”, available on: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EVWiwd0P0c0, 7 Sept 2016.

- Tom of Bedlam’s Song: Anonymous Ballad, orally transmitted, first written down in an anonymous commonplace book 1620. Text available on: http://www.thehypertexts.com/Tom%20O’%20Bedlam’s%20Song.htm.

- Thomas Harman, A Caveat, loc. 872 et seq.

- Ibid., loc. 898.

- Ibid., loc. 1414.

- W. Shakespeare, The Taming of the Shrew, Entire Play, FSL.

- W. Shakespeare, Love’s Labours Lost, Entire Play, FSL.

- W. Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra, Entire Play, FSL.

- W. Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, Entire Play, FSL.

- W. Shakespeare, Henry IV, Part 2, Entire Play, FSL.

- W. Shakespeare, Henry IV, Part 1, Entire Play, FSL.

- W. Shakespeare, Richard III, Entire Play, FSL.

- Frederich Engels, Letter to Karl Marx, December 10, 1873, Marxist Internet Archive, available https://www.marxists.org.

- This theory was widely developed by Soviet critics in the 1960s. Let A. Smirnov’s “Shakespeare, the Renaissance and the Age of Barroco”, dans Roman Samarin and Alexander Nikolyukin (eds), Shakespeare In the Soviet Union: A Collection of Articles, London, Progress Publishers, 1966, p. 58-83 stand as an example.