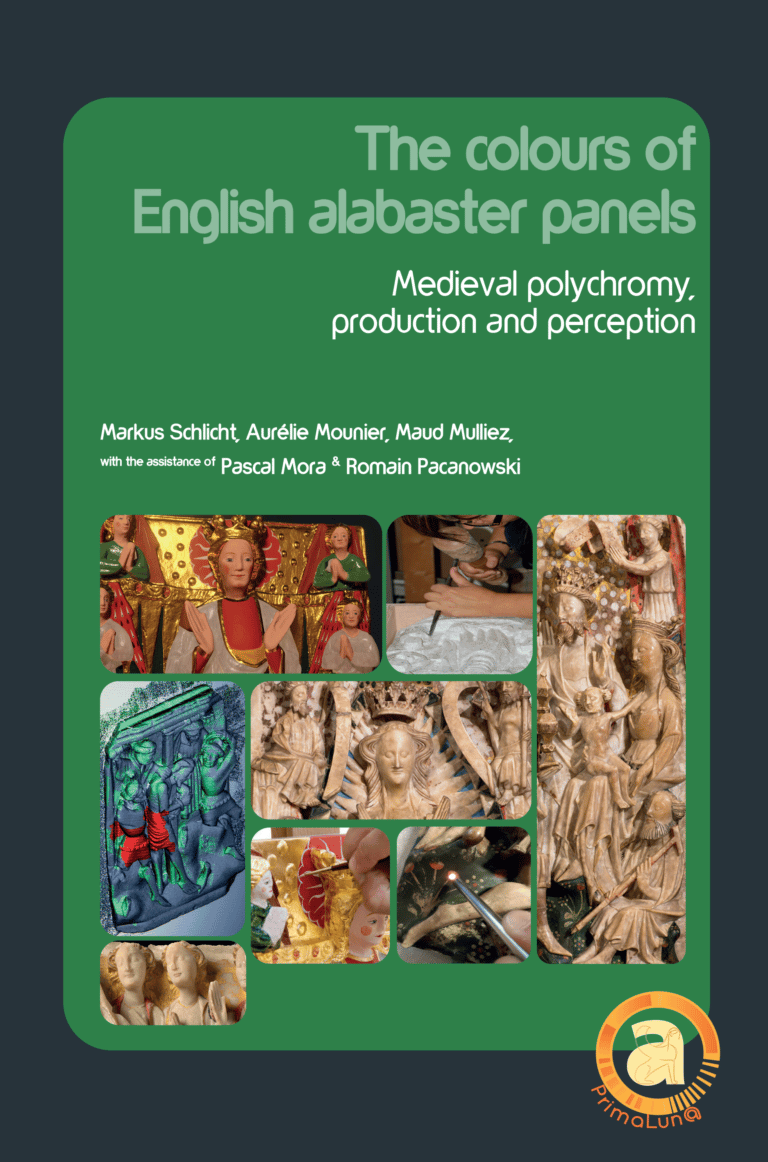

While in the previous chapters we have studied the pigments and colours used on English alabasters, their standardised use, the aesthetic principles governing their combination and their moral codification, we have not yet considered the properties and visual effects produced by medieval polychromies. What were their surface aspects, their finishes, the intensity of their colours, their interactions with alabaster? How were they created and applied, and what difficulties might the painters have faced? In order to gain a better and more accurate picture of these material issues, an alabaster facsimile of an English panel was carved and then painted. Although its colouring is atypical, the panel of the Assumption in the Musée d’Aquitaine in Bordeaux was chosen for this experimentation.

It is indeed thanks to a close collaboration with the staff of the museum, in particular with its stone sculptor, Amandine Bély, that this copy could be realized. The observations made and the results obtained during the creation of the work will be presented in the order of the different stages of the work. They have been dealt with in greater detail in another article, to which we refer the interested reader.1 Here we will focus on the elements that can inform us about how an alabaster panel was made in the Middle Ages.

The Carving

As it was not possible to acquire alabaster of English origin – the quarries are no longer worked – the copy was made using a variety from Puebla de Hijar in Teruel, Aragón (fig. 49-50). The two types of alabaster are comparable in terms of the fineness of their grain, which allows a high gloss polish to be obtained, and their general physical properties, such as their softness and, consequently, the possibility of shaping them without great physical effort. While both are white in colour, it is not sure that their translucency is comparable. Judging from the appearance of recent fractures in medieval panels, the white of Derbyshire stone appears more dense and opaque than that of Spanish alabaster.2 Since this possible difference in translucency is most apparent when the two varieties of alabaster are backlit, its visual impact seems relatively limited. Inserted in altarpieces or small cases made of oak boxes devoid of openings at the bottom, medieval alabasters could only be lit from the front or from the side.3

For the carving work, the raw parallelepiped panel was first sawn to match the dimensions of the original panel. When the block was acquired, the surfaces were already flat and smooth, but not polished. Once the main lines of the composition had been reproduced on a transparent film, fixing the position of the figures and their attitudes, they were replicated on the blank slab (fig. 51). The sculptor then began to remove material from the areas roughly outlined by the preparatory drawing. As the contours were gradually freed up, the graphic markers used as a guide by the sculptor, drawn with a pencil or a metal point, were renewed regularly. As the carving progressed, these markers can become more and more finely detailed (fig. 52, 54). It seems quite possible that the medieval alabasterman proceeded in a similar way.

The alabaster was carved using small straight chisels and gradines (fig. 53). They were propelled by a mallet, sometimes wooden, sometimes metal.4 Tight folds and other cramped areas were carved out with riffles (fig. 54). In the Middle Ages, carvers may also have used drill bits – even though it was not necessary to use them for our facsimile – in order to prepare for certain deep cuts.

Once the alabaster had been rough-cut, the final stages of the work were carried out using a sculptor’s pantograph (fig. 54). This is an instrument made up of sliding metal rods which, when fixed to the original, allow a stylus to be moved towards the point of the relief to be reproduced. By locking the position of the stylus, the X, Y and Z spatial coordinates are ‘registered’. After transferring the pantograph to the blank panel, the tip of the stylus indicates to the sculptor the precise position of the point to be reproduced.After the actual carving work was completed, the panel was polished. For practical reasons, the polishing was done with very fine-grained pumice paper, not with sand and goatskin, the materials probably used by medieval alabaster sculptors according to Cheetham.5

As we had not yet correctly understood the sense of hollowing out the reverse side of the panels, as was commonly done in the Middle Ages, we did not reproduce this detail. Indeed, the lower part of the back of medieval alabasters was almost always cut out (fig. 56-57). This recess was probably not so much meant to reduce the weight of the panel to make it more transportable, as is sometimes said, but to facilitate its handling during the cutting and painting process.6 During these phases of work, the Assumption facsimile was often laid flat, if only to avoid paint drips.7 The recess in the reverse side allows the hand to slip underneath the alabaster, to turn it and thus to have easier access to its various parts, both with the chisel and with the paintbrush.

In the Middle Ages, the reverse side was also pierced with two to four holes made with a drill. In these holes, the alabaster sculptors inserted copper wires, sealed with liquid lead, which were used to attach the panel to the bottom of the wooden case intended to house them8 (fig. 57). Finally, the reverse side of the panel frequently shows engraved marks, which were probably used to identify the panels belonging to the same altarpiece (and not to mix them up with other tables under execution), so that they could be assembled correctly when they were completely finished.9 The entire copy of the Assumption panel required about sixty hours’ work. However, a medieval sculptor could have made a panel in much less time; according to Amandine Bély’s estimate, twenty-five to thirty hours would have been sufficient for an experienced sculptor working in free carving. The length of time required to produce the facsimile is due to the use of the pantograph and the objective of reproducing a medieval model precisely, both of which slow down the work considerably.

The Painting

Before the actual painting, the sculptor applied gesso nodules, made from alabaster dust and glue, to the upper background of the panel (which was to be gilded in a second process).10 This was a delicate operation, the main difficulty of which lay in ensuring that the nodules adhered well while giving their surface a regular curvature. The sculptor or painter – quite often probably the same person11 – could also carve incisions in his sculptures. Most of these incisions were used to determine the width of the gilded edgings, especially in the case of hems of a certain length, such as the trimmings of a coat or bed sheet.12 (fig. 58). The irises of the eyes also seem to have been incised at times. This is the case for the Virgin of the Nativity in the altarpiece of Saint Michel in Bordeaux, or the Virgin of the Annunciation in Saint Nicolas du Bosc. These incisions made it possible to determine the direction of the gaze beforehand and to ensure that the irises were parallel (fig. 59).

For practical reasons, the gilding was probably done before the paints were applied (fig. 60). Areas where the paint is not yet completely dry attract the gold-leaf, which inevitably adheres to them. Unless you wait for a long period of time – several weeks – it seems preferable to apply the gilding before the painting, otherwise there is a risk that gold particles will settle in places where this was not intended.13

Gilding, in the case of alabaster, was done with a mixtion, i.e. the leaf was fixed to the support by means of an oil-based glue. These mixtions were tinted with yellow or red ochre pigments and red lead (minium). The colour of the pigment used to tint the mixtion influences the shade of the gold. The use of red lead accelerates the drying of the mixtion and thus shortens the waiting time for the gold-leaf to be applied; in addition, the red lead gives the gold-leaf a particularly smooth finish (fig. 61). The leaf is applied as soon as the mixtion is almost dry, after several hours, between two and twelve depending on the environmental conditions (hygrometry, temperature, ventilation, etc.), but also on the quantity of lead (minium) it contains. Placed on a gilding pad, the gold-leaf is then cut to the shape and approximate dimensions of the area to be covered. By means of static electricity, the leaf is picked up with a gilder’s tip (a flat brush with long bristles) and layered on the area covered with mixtion. The gold adheres to the surface in an irregular manner. It is then necessary to perfect the adhesion by expelling the air with a special burnishing brush. Unlike water-based gilding techniques, suitable for wooden surfaces, it is not necessary to polish the gilding with an agate. Excess gold, which is deposited beyond the areas covered with mixtion, can be easily removed with a brush.

Observations on pigments and binders

Although alabaster is polished, and therefore seems to offer little adhesion, the paint can be applied without an undercoat.14 Our own analyses and those of other research teams confirm that this was the norm for medieval English alabaster.15 As mentioned above, there are at least three exceptions among the alabasters in Aquitaine. The St Peter in the panel of the Elect entering Paradise in Libourne wears a cloak with a blue lining painted with azurite. This blue layer is superimposed on a sub-layer of dark grey, which densifies the colour while obscuring it somewhat; the same applies to the nimbus of the Christ of the Resurrection of Saint Michel, whose azurite is similarly laid over a blackish undercoat (fig. 62). The green paint (copper resinate) on the robes of the Assumption angels in the Musée d’Aquitaine was deposited on a layer of yellow ochre or lead white that would have turned yellow. As the resinate is translucent, the presence of the undercoat creates a yellow-brownish shade.

On the medieval panels, the binder used was oil; for our tests, we used linseed oil. Since these samples showed a rapid yellowing after only a few months, one may wonder whether the medieval painters did not use other varieties of oil, or whether they did not know of procedures to avoid this yellowing.

Not all pigments react in the same way when applied to alabaster. According to the results of physico-chemical analyses, the Aquitaine panel painters mainly used mineral pigments, namely lead white, yellow ochres, red lead (orange), cinnabar (intense red), red ochres (deep red to brown), copper resinate and verdigris (green), and sometimes also azurite (blue). Dyes or lakes, of organic origin, appear much less frequently.16 Of these, indigo is the most frequently used; an unidentified organic yellow, present on the three Libourne panels, has not been detected elsewhere. According to our experiments, it is much more difficult to obtain homogeneous and covering surfaces by using organic pigments, such as stil de grain or buckthorn (yellow), than by using mineral dyes (fig. 63-64). Since medieval alabaster polychromy has just this uniform finish, which was clearly sought after by English painters, we believe that the different properties of mineral and organic pigments at least partly determined the prevalence of the former over the latter. It is possible that the greater stability of mineral pigments and their sometimes greater intensity also contributed to their preference.

Even from one mineral pigment to another, the effects produced can vary significantly. This is true of their covering power. A red ochre, for example, forms a covering opaque layer from the first coat, whereas yellow ochres often require a second or even a third coat. Depending on the number of coats, the surface appearance of paints can vary. A single coat often results in a rather matt appearance, which is made more satin-like by the application of a second coat (fig. 65).17 Given the generally smooth appearance of medieval paint layers, the painters had to grind the grains finely. However, some pigments, such as azurite, should not be ground too finely, otherwise they lose the burst and intensity of their colour.

Copper resinate is a special case among paints based on mineral pigments. It is not a powder but a viscous, translucent liquid.18 The paint is susceptible to drying, so it has a short storage life and must be produced with this in mind. The colour of copper resinate can vary considerably depending on how long the mixture of Venetian turpentine, oil and verdigris is heated, changing from a bluish shade to green, then to brown (fig. 66). As for its appearance, once applied to the alabaster, it can be seen that, while it becomes darker and denser with an increasing number of layers, it still retains its translucency. It is also distinguished by its very shiny appearance, which is apparent from the first coat. However, this shininess can easily be removed by rubbing. Thus, on the original panels, the glossy appearance of the surfaces in general has not been preserved (fig. 40).

The question arises as to whether gloss was not one of the qualities actively sought after by the alabastermen. The glossy finish – even if it is a different type of gloss – characterises not only the green copper resinate, but also the brilliant white of the polished alabaster and the gilding, i.e. the materials that colour the most important surfaces of medieval panels. As other physico-chemical studies have shown, the green backdrops of English alabasters were often covered with a glaze, i.e. a layer of oil containing a few grains of green pigments.19 These glazes also gave the surfaces a glossy or satin appearance. Although the physico-chemical analyses carried out within the Aquitaine corpus have not allowed the detection of glazes (whether they were applied to green or other colours), it cannot be excluded that they have disappeared over the course of time; further research should be carried out on this subject. Even if such glazes had not been used for colours other than green, the medieval panels probably had at least a satin (and not a matt) finish, as the painted copy of the Assumption in the Musée d’Aquitaine illustrates (fig. 67).

Notes

- Mulliez et al. 2022.

- The Throne of Mercy in Castelnau de Médoc has unfortunately been vandalised twice, in 2018 and 2019, so that the interior of the stone has been exposed in several places. The breakage of a panel representing the Throne of Mercy, kept in the Musée Vivenel in Compiègne, also shows a very dense and bright white.

- The original wooden framework for altarpieces and single panels are rarely preserved. Those containing single panels can still be found in the Burrell Collection in Glasgow (three examples), the V&A Museum in London, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, Worcester Cathedral and the National Museum in Reykjavik (from Selardalur Church). See also Nelson 1920, 57. For the wooden frames of altarpieces, too numerous to list here, see for example those of Saint Michel of Bordeaux in New Aquitaine, or elsewhere in France at Saint Nicolas du Bosc and Évreux (from La Selle). Philip Nelson has written a study specifically dedicated to the woodwork of alabaster altarpieces; see idem 1920.

- Inferring from the practices of twentieth-century sculptors, Cheetham 2005, 24 assumed that alabaster was carved without a propellant, mainly to limit the risk of breakage.

- See Cheetham 2005, 24, note 144.

- See more in detail in Mulliez et al. 2022. As Cheetham 1984, 25 has already stated, it is probably appropriate to distinguish between large sconce statues and narrative panels. The statues can indeed reach a much lower weight when they are completely hollowed out, as is the case with the Saint Martial of Bordeaux Cathedral or the Pietà of Burghley House, Lincolnshire (inv. no. EWA08599). The panels, on the other hand, are only hollowed out in their lower part, and the resulting lightening is much less significant.

- In our experiments, for example, the copper resinate, which remains viscous for several days, tended to flow slowly downwards once the panel had been put in the upright position.

- These looped copper wires were passed through holes in the bottom of the wooden framework. Wooden pegs, passed through the loops in the back of these wooden frames, held the panels in place.

- See Cheetham 1984, 25. See also Nelson 1920, 60.

- We chose organic glue, in this case rabbit skin glue. For more details, see Mulliez et al. 2022.

- See for example the few remarks on this subject in Schlicht 2019, 190-191. In the case of prestigious works, the commissioner sometimes called in a specialist painter, as was the case for the altarpiece in St George’s Chapel, Windsor: William Burdon was paid £40 in 1367-68 to paint a panel for the Great Canons’ Chapel and an altarpiece in the upper chapel, the sculpture of which was done by Peter the Mason of Nottingham (Cheetham 1984, 27).

- It seems unlikely that the incisions are the result of cutting the gold-leaf after it has been applied as the leaf is so thin that the risk of tearing it would have been very high.

- For more details, see Mulliez et al. 2022.

- For a discussion of the physical characteristics that allow paints to adhere to alabaster, see Harris 2020, p. 52-53.

- See for example Colinart & Klein 1997, 99. See also Pereira-Pardo et al. 2018, 5. While confirming the absence of undercoats in most cases, Cheetham 2005, 26 states: “grounds […] were used […] sometimes to add depth and hue to the surface coat of a thinner colour such as vermilion glazes, blue smalt or azurite”. According to Land 2011, 65-66, the use of azurite requires an undercoat (lead white and/or carbon black).

- The study conducted by Pereira-Pardo et al. 2018 on the Kettlebaston alabasters and the Virgin and Child in the British Museum concludes that only one organic pigment is present, in this case kermes (pink), the others being all mineral in nature: cinnabar, red ochre, red lead, verdigris, copper resinate, azurite, lead white and carbon black. Similarly, the colours of the Rouvray altarpiece are composed of mineral pigments, with the sole exception of organic blue (probably indigo; see Colinart & Klein 1997, 99). The English alabasters from the Basque country, especially the Passion Altarpiece from Plentzia, use only mineral pigments (Castro et al. 2008, 763).

- Sometimes the same pigment applied to the same panel can produce different surface effects. For example, the first layer of cinnabar used for the Assumption facsimile had a matt appearance in some areas, while others appeared satin. The reasons for this phenomenon could not be clarified: do the respective areas have a different porosity?

- The green copper resinate was made according to the instructions given by Mayerne 1620, fol. 31: “Pour faire le vert transparent qui s’applique sur un fonds d’or ou d’argent. Prenés un petit pot. Thérébentine de Venise 2 onces, huile de thérébenthine 1 once et demie. Vert de gris broyé grossièrement sur le marbre 2 onces. Mettés-le parmy la thérébenthine et huyle sur les cendres chaudes. Prenés une pièce de verre, et en mettés une goutte dessu advisant si la couleur vous plaist. Après mettés y la grosseur d’une noix de terra merita (curcuma). Laissés bouillir doulcement, jusques à tant que vous voyés que vostre vert soit fort beau. Passés tout doucement à travers un linge.” [To make the transparent green which is applied to a gold or silver ground. Take a small pot. Venetian turpentine 2 ounces, oil of turpentine 1 ounce and a half. Verdigris crushed roughly on marble 2 ounces. Put it with the turpentine and the oil on hot ashes. Take a piece of glass, and put a drop of it on it to see if you like the colour. Then put in the size of a nut of terra merita (turmeric). Let it boil gently until you see that your green is very beautiful. Pass it gently through a cloth.]

- Cheetham 1984, 56-57; Colinart & Klein 1997, 99, about the Rouvray altarpiece; Land 2011, 72.