Introduction1

The western part of present-day Slovenia belonged to Regio X of Italy in the Early Imperial Period and for the most part to the province of Venetia et Histriain the Late Roman period. It is a transitional area, crossed by the prehistoric Amber Route and later the viae publicae Aquileia–Emona–Carnuntum and Emona–Sirmium that connected the northern Adriatic with the central Danube Basin and the northern Balkans.

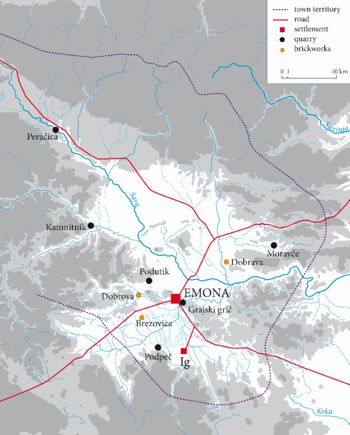

The area was divided between several towns. Its southern part, mainly the Kras plateau2 and northern Istria, belonged to the ager of colonia Tergeste. The ager of colonia Aquileia included the Vipava Valley with the hills of Goriška Brda and stretched along the main eastbound road to the trading reloading post at Nauportus. At the north-eastern edge of Regio X was colonia Iulia Emona (present-day Ljubljana), situated on the crossroads of major land routes and on a navigable waterway; its ager predominantly extended north of the town and probably also encompassed the eastern Julian Alps. The western part of the Julian Alps with the Soča Valley probably belonged to the ager of Forum Iulii.

At the end of the 1st century BC and during the 1st century AD, the area underwent great changes in settlement pattern and economy. The administrative reorganisation, immigration from the Apennine Peninsula and advanced Romanisation led to new forms of land-use and new types of settlements (towns, secondary settlements and villae). In consequence, it also led to substantial changes in the non-agrarian production of the area3.

The aim of this contribution is to give an overview of the archaeological evidence from the town of Emona and the countryside pertaining to the manufacture of pottery that is documented best, but also to metallurgy, glass making, quarrying and stonemasonry. The available evidence will be analysed and compared according to the types of production and their location.

Emona

The first Romans settled at Emona roughly in the mid-1st century BC, in proximity to the agglomeration of the autochthonous population on the right bank of the River Ljubljanica. In the Middle and Late Augustan period, a military fort was constructed nearby. The colony Iulia Emona was established at the end of the Augustan and beginning of the Tiberian period on the opposite, left bank of the river4.

Pottery production

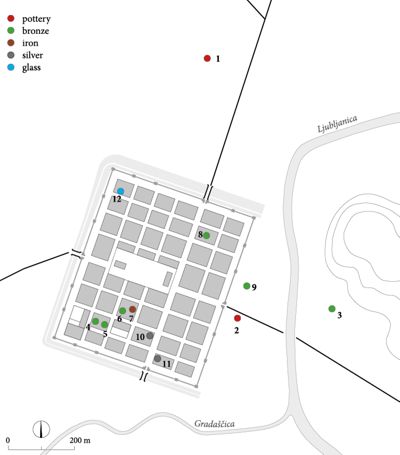

The archaeological evidence for pottery production at Emona is relatively poor (fig. 1: 1, 2). Brief reports on the finds that came to light during the construction works in the 19th century, as well as a paper on a pottery kiln reveal a potters’ quarter in the northern suburb5. An isolated kiln was also unearthed in the eastern suburb6. Neither wasters nor stamps as trade-marks of local potters are known from the town.

Roughly two decades ago, the local pottery production at Emona was studied with the aim of defining the most common local fabrics at Emona7.

The studyhasshown that the majority of utilitarian vessels (platters, dishes, cups, beakers, jugs, flagons, fineware jugs, tazze etc.) share the same macroscopic characteristics. The fabric was named F 7 (fig. 2) and its grey (reduction-fired) version F 8. A relatively large quantity of vessels made in this fabric was found in the fill of the pottery kiln in the potters’ quarter, which was seen as evidence of its local production. The potential local sources of Fabric F 7/F 8 were the clay deposits sampled at five locations in Ljubljana.

The ensuing archaeometric research included chemical (WD-XRF; 35 pottery and 11 clay samples) and mineralogical analyses (thin-sections; 16 pottery samples) as well as matrix-grouping by refiring (MGR; 15 pottery and 11 clay samples). It was undertaken to verify the homogeneity of the fabric and the hypothesis on its local origin.

The results have shown that Fabric F 7/F 8 forms a chemically homogeneous group of roughly the same mineralogical composition. Matrix-grouping by refiring (MGR) has confirmed that the differences in appearance were due to different firing conditions that generally reached between 1000 and 1100°C. Furthermore, it has been shown that the fabric is comparable with the clay washed down the Rožnik hill, hence most likely local in origin.

Three pottery workshops and brickworks have thus far been recorded in the vicinity of Emona (Brezovica, Dobrova and Dobrava). However, only the locations are known and not their products (fig. 5)8.

Bronze and iron metallurgy

A large amount of fragmented bronze objects was found in a wooden building with a hearth at the Gornji trg 3 site, on the right bank of the Ljubljanica (fig. 1: 3). They include lorica segmentata fittings, belt buckles, bronze plates, pieces of wire and semi-finished products comprising a belt buckle and a buckle tongue. The objects are probably evidence of a workshop that produced or repaired parts of the military equipment for the army stationed in the nearby Middle–Late Augustan fort9.

Most of the evidence for metallurgy comes from the southern part of the colony, where large-scale excavations took place at the beginning of the 20th century10.

In Room 30 of Insula 6 (fig. 1: 5; 3: 30), two smelting furnaces were unearthed, constructed of stone slabs with a domed clay covering. A casting or moulding pit filled with fine sand was discovered nearby. The small finds consisted of a stone crucible, a stone weight, a large quantity of melted bronze, and slag. The remains were interpreted as a foundry, dated to the mid-1st century AD on the basis of the coins of Claudius11.

A channel and three pits lined with burned clay were found in Rooms 66 and 67 of the same Insula 6, but in a different part (fig. 1: 4; 3: 66–67). According to the excavator, they might represent the casting or moulding pits of a foundry from the Early Imperial period12.

A foundry was certainly located in Insula 11 (Rooms 63 and 64; fig. 1: 6). Phase 1 of the foundry was unearthed in Room 63 and consisted of an oval hearth constructed of stones and bricks, and an adjacent channel containing a large quantity of melted bronze, bronze plates and slag. Ash and burned material was found all over the room. Phase 1 presumably dates to the Early Imperial period. In Phase 2, Room 63 was filled up and levelled. A pit containing ash and pieces of slag was located in the Room 64. A stone mould for casting rings was found in nearby Room 5813.

In the eastern part of Insula 11 (Room 49; fig. 1: 7), a forge herd made of bricks and a stone slab was excavated with several iron tools found in the vicinity. The forge is not precisely dated14.

A smelting furnace from the Early Imperial period was investigated in Insula 39 (fig. 1: 8)15.

Two not precisely dated furnaces with pieces of iron and copper slag are reported from the eastern suburb (the Dvorišče SAZU site; fig. 1: 9)16.

Goldsmith’s workshops

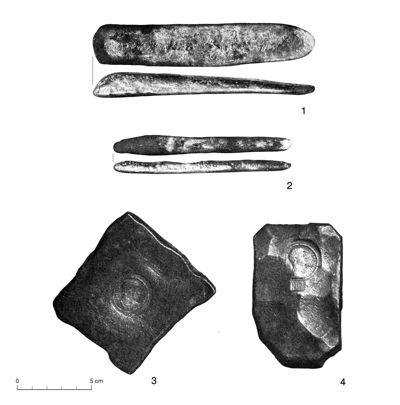

A pot containing nine silver bars and 50 gold coins was found in Room 8 of Insula 4, which opened to the street leading from the south town gates to the forum (fig. 1: 10). The last gold coin of Constantius II was minted in 353. The bars of an irregular elongated form weighed between 376.10 and 77.23 g and contained 93.75% of silver (fig. 4: 1, 2). They were probably prepared by melting old silver objects. Pieces of mercury were discovered in the same room; mercury was needed in the process of gilding. Walter Schmid presumed that the hoard was the property of a goldsmith17.

Two roughly quadrangular silver bars were found in a room near the south gate of Emona (Insula 15; fig. 1: 11). They weigh 319 g (fig. 4: 3) and 640 g (fig. 4: 4) respectively, i.e. approximately one and two pounds. The heavier bar contains 94.12% of silver. Each of the bars bears two stamps: an image of Magnentius inside the inscription D N MAGNEN/TIVS P F AVG above and a rectangular stamp with two rows of letters below. The letters CAQPF survived in the lower row of the rectangular stamp on the lighter bar. On the heavier bar, the letters [-–-]FLA survived of the rectangular stamp. Walter Schmid presumed this hoard was hidden in 351, when Magnentius passed Emona18.

The silver bars from Insula 15 are not necessarily connected with those from nearby Insula 4, though the locations may indicate goldsmith’s workshops lining Emona’s cardo maximus.

Glassmaking

A large quantity of crushed glass was discovered in a building located in the north-western part of Emona (Insula 31; fig. 1: 12). Fragments of vessels, window glass and melted glass were partly fused to the bricks in a presumed debris layer. The layer with these finds was dated to the end of the 4th and beginning of the 5th century AD on the basis of coin finds (388–402) and forms of glass vessels. The excavator presumed the existence of a glass workshop with a furnace19. However, the absence of characteristic glass working waste has later led to suggestions that the assemblage might have been discarded glass intended for recycling or the remains of a shop with glass products20.

On the other hand, special forms of glass vessels, such as glass ladles and oviform beakers, and their limited distribution indicate that local glass production did exist at Emona in the second half of the 1stand the first half of the 2nd century AD21.

A chunk of raw glass made with natron was found near the River Ljubljanica in the vicinity of Nauportus, 18 km west of Emona. It may have been lost during water transport22.

Quarrying and stonemasonry

(from Horvat & Sagadin 2017, fig. 6; Djurić & Rižnar 2017, fig. 1).

The stone used in Emona mainly came from local and regional sources. Six quarries have been identified in the region (fig. 5)23.

Three stonemason’s workshops using Podpeč limestone were active in the wider Ig area. They began operations already in the 1st century AD, while the bulk of their production falls between the mid-2nd and mid-3rd centuries AD24.

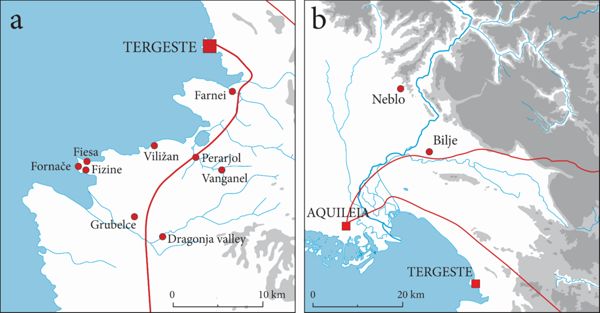

Pottery production in northern Istria

On the west coast of northern Istria (part of ager Tergestinus) with its mild Mediterranean climate and favourable conditions for living and intensive agriculture (cereals, wine, olives), many agricultural estates were established at the end of the Late Republican period and the Early Empire. There is evidence of small farms, as well as minor, medium-sized and large estates (villae rusticae), also luxury villae maritimae with harbours along the coast25. Clay deposits, recent brick factories and archaeological evidence suggest the existence of brick and pottery workshops (fig. 6: a)26.

a. Northern Istria; b. Goriška brda and the Vipava Valley.

Until the mid-20th century, brick factories still operated at Viližan near Izola and Fiesa near Piran27. Between Piran and Portorož, toponyms such as Fornače and Fizine supposedly originate from the Latin words fornax>fornaces and ad figlinas28. These sites also yielded physical remains from the Roman period that include architectural complexes interpreted as either villae rusticae or villae maritimae29.

Roman kilns were reportedly found at Vanganel, Viližan30 and in the Dragonja Valley at Kaneda near Sečovlje31, but are unknown in detail and unverified by modern field surveys.

Ceramic wasters are known from Farnei near Muggia, at the mouth of the River Osoppo in the Muggia Bay32.

A dump of failed small Dressel 6B amphorae and kiln remains were found at Perarjol (Pri Angelu and Nova Šalara sites), near the mouth of the River Badaševica in the Koper Bay. Remains of a villa rustica are known in the vicinity. Ceramic wasters indicate that Dressel 6B amphorae were produced in three sizes: the standard form with a funnel-like rim, typical of the second half of the istand (first half of) the 2nd century AD33, and its smaller variants of Fažana I (or Grado I/Aquincum 78) and Fažana II (or Grado II and Bónis 31/5)34. The surviving bottoms are of an identical knob-like form. Unfortunately, they were not stamped35.

At Grubelce near Sečovlje, a vast building complex of a villa rusticawith associated warehouses was excavated in 1982. Fragments of amphorae were recovered, mostly Dressel 6B or its smaller variants of Types Fažana I and II. Undefined ceramic waste indicates pottery or brick production facilities located in the area36.

Dressel 6B amphorae were used for the transportation of the north Adriatic olive oil, especially that from the Istrian Peninsula. Large amphorae of this type were produced from the mid-1st century BC to the 2nd century AD. Small variants of the Dressel 6B type were supposedly used for transporting olive oil from the mid- 2nd to at least the 4th century AD37, as well as for transporting the sought-after Adriatic fish products of muria, liquamen and garum. Ancient writers mention their production on the coasts of Dalmatia (Plin., HN, 31.94: muria) and Istria (Cassiod., Var., 12.22: garismatia), where many fishponds have been excavated38. The fabrics of the small Dr. 6B amphorae are heterogeneous, suggesting production in different workshops39.

The stamps on tegulae attest to a great concentration of ceramic workshops in northern Istria in the first two centuries AD40. Most stamps appear in small quantities and have a limited distribution area, confined to ager Tergestinus, northern Istria or even smaller areas. Most of them were used on tegulae, as well as on Dressel 6B amphorae, which is a particular feature of the region. The modest and limited distribution of these tegulae indicates that brick making was an additional activity in the local estates.

The fabrics of the amphorae and tegulae with stamps are identical to those of local tableware, oil lamps, fishing-net sinkers, loom weights, dolia and other building material (bricks etc.). The recovered Dressel 2-4 and flat-bottom amphorae, both used for wine transport, are in the same fabric and indicate local wine production41.

The basic function of the pottery workshops in northern Istria was thus the production of amphorae for olive oil, wine and fish products. In addition, they manufactured all other ceramics and building material used on the estates.

The owners of the north Istrian estates in the Early Imperial period were members of the Tergestine local elite or even more highly ranked individuals. The stamp L. Q. THAL. on bricks is characteristic of the area around Izola and Koper. Another presumed landowner is the knight P. Iturus Sabinus, libertus of a duumvir; his family name indicates an Oriental origin42. The Tergestine family of Tullii Crispini supposedly owned the villa rustica at Školarice, where olive oil and wine were produced in large quantities. Their urban residence was the domus excavated at Piazza Barbacan in Trieste43.

Access to good clay in the flysch area of northern Istria led estate owners to establish their own pottery workshops following the recommendations of the ancient writers on how to optimise expenses of a fundus. Like at Fažana in southern Istria, one pottery workshop could serve several estates of the same owner44.

Pottery production in the Vipava Valley and Goriška Brda

The fertile Vipava Valley and Goriška Brda were parts of the Aquileian ager with intensive agriculture45.

Archaeological excavations at Neblo near Borg, on the south-western hilly fringes of Goriška Brda (fig. 6: b), were carried out in 1986 and revealed ceramic waste, expanded ceramic vessels and bricks that proved the existence of a pottery and brick production complex. The original size of the workshops could not be established, but field survey results suggest at least three production areas, one of them in the lowland. The pots with incised shoulder decoration were supposedly made here. Many rim fragments belonged to small amphorae similar to Type Fažana II. Numerous brick fragments with the stamps AGATOCL. BARB. and BARB. AGATOCL. are perhaps evidence that the workshop was owned by the wealthy Aquileian family of the Barbii and that the production was managed by one Agatocles46.

The Ad Fornulos mansio was located along the Aquileia–Emona road, somewhere between Bilje and Bukovica. At Bilje (the Križcijan site; fig. 6: b), excavations revealed the remains of a large building (probably a drying facility) with a small pottery kiln and a large rectangular brick kiln, all dated to the Early Imperial period. Other finds include fragments of a dolium and seventeen bricks with the stamp TIB. VETTI AVITI. The workshop probably developed owing to rich and quality clay deposits in the area47. It can be considered a subsidiary of major Aquileian workshops, which the distribution of the stamps shows to have exported their products across north Italy, Istria and the Dalmatian coast48.

Production of iron

Traces of metallurgy were detected in two settlements along the main roads crossing the area (fig. 7). In Fluvio Frigido, a large quantity of iron slag was found in a habitation layer from the Early Imperial period. Forging slag prevails, suggesting the existence of a smithy. Partly refined bloom was discovered as well49.

Several smelting furnaces from Blagovica (probably the Ad Publicanos roadside station), which operated in the mid-4th century, probably produced limited quantities of iron50.

Most of the evidence of iron production comes from settlements not located near the main roads.

In the minor Roman settlement at Mengeš, the remains of a wooden building dated to the istand beginning of the 2nd century AD include a hearth associated with large amounts of iron slag, tuyeres and fragments of furnace lining with slag adhered to them; these have been interpreted as the rests of a smelting furnace51.

The villa rustica in Polje near Vodice also provided evidence of iron production. A geophysical survey revealed its ground plan, while excavations conducted in a narrow belt along the edge of the villa unearthed a sunken roasting hearth (2.72×1.65 m; 0.70 m deep), as well as two reusable smelting furnaces (0.77×0.64 m), also slightly sunken and associated with a waste-pit for slag. Their interiors were coated with several layers of clay and lined with stones. They contained large quantities of smelting slag. Also unearthed were two domed forging hearths, as well as tuyeres and some forging slag.

These remains reveal two phases of iron production at Polje: ore smelting and forging the final products. The geophysical survey indicated the presence of many other furnaces in the unexcavated part of the villa. The villa is dated from the 2nd to the early 5th century AD, though metallurgical activities seem to have started in the second half of the 3rdand lasted into the 4th century AD52.

Tuyeres and iron slag were also found in the minor Roman settlement at Zasip53, iron slag in the villae at Mošnje54 and Bistrica near Tržič55, iron bloom in the villa at Rodine56. All sites are dated to the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. A Late Roman workshop with a forging hearth and a smelting furnace was discovered in a small settlement at Šmartno near Cerklje57.

The hilltop settlement at Ulaka saw continuous occupation from prehistory into the Roman period, when it probably retained its role as a local centre of autochthonous population. The Roman-period settlement had concentric rows of buildings, most of them sunken houses with stone foundations and a wooden superstructure. Eight of them yielded traces of metal working that comprised vaulted fireplaces, anvil bases, tuyeres, iron slag and a set of blacksmith’s tools (hammer, pincers and a file). A group of six adzes indicates serial manufacture. The ironworking activities are dated from the second half of the 2nd to the end of the 4th century AD58.

The Roman-period settlement on the hill Ajdovščina above Rodikwas located within the rampart of the prehistoric hillfort. As the centre of the Rundictes, it was continuously occupied at least till the end of the 2nd century and flourished again from the late 4thto the mid- 5th century AD59. Geophysical prospection brought to light the remains of ironworks (smelting or forging furnaces) and deposits of metallurgical waste at the edge of the settlement. They have been ascribed to the last habitation phase60.

The Late Roman settlement on Ajdovski gradec in the Bohinj area was also located within the ramparts of an Iron Age hillfort. Geophysical field survey revealed large amounts of slag that could originate from the last phase of habitation61.

Small production centers

Besides iron metallurgy, Ulaka also yielded evidence of other non-agricultural activities. Bronze slag and crucibles point to bronzework production62. The large quantities of two-handled bowls of a limited distribution suggest local pottery fabrication in the second half of the 1st and the 2nd centuries AD63.

In the vicus of Nauportus, a semi-product of a fibula and pieces of sheet bronze reveal the fabrication of bronze objects64.

Conclusion

Emona as an urban centre had the most diversified non-agricultural production in the area. Archaeological evidence proves the manufacture of pottery and objects of iron, bronze, silver and glass. The distribution area of these products does not seem to be very large, for the most part hardly exceeding the boundaries of the town territory. South of Emona, the minor settlement at Ig specialised in stone masonry, with the colony of Emona as its main market.

Northern Istria shows a concentration of rural estates with associated pottery workshops. They produced amphorae (mainly Dressel 6B and similar), but also tableware, cooking ware and building material. These estates, in the Early Imperial period owned by the members of the local elite, were making olive oil, wine and fish products, and optimised the expenses of agricultural production with their own pottery workshops.

The pottery and brick workshop at Neblo in Goriška Brda was probably too large for the needs of a single estate. Similarly, the Bilje complex in the Vipava Valley appears to be mainly a brick production centre supplying a wider market.

As for iron production, it seems to have been an important activity in the minor settlements and villae in the hinterland of Caput Adriae. The forging and smelting in Fluvio Frigido and Ad Publicanos might have been connected with their location along the main public road and the requirements of the constant traffic. Specialisation in either primary processing of iron or working the iron into final products is apparent in the hilltop settlements at Ulaka, Rodik and possibly also Ajdovski Gradec in Bohinj. These settlements were more or less continuously inhabited from prehistory to the end of the Roman period and their prosperity might in fact be connected with iron. Ulaka stands out among these sites as iron forging was accompanied with other types of production (bronze, pottery).

The villa at Polje near Vodice specialised in large-scale iron production. Similar specialised activities can be presumed in other lowland sites, villas or minor settlements that yielded rests of furnaces, tuyeres and iron slag. Their distribution and number might indicate that large-scale iron production took place in the area north of Emona.

References

- Auriemma, R. and Karinja, S., ed. (2008): Terre di mare. L‘archeologia dei paesaggi costieri e le variazioni climatiche, Trst-Piran.

- Bezeczky, T. (1998): The Laecanius Amphora Stamps and the Villas of Brijuni, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Denkschriften 261, Wien.

- Bezeczky, T., ed. (2019): Amphora research in Castrum villa on Brijuni island, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Denkschriften 509, Archäologische Forschungen 29, Wien.

- Bezeczky, T. (2019): “Italian and Istrian Amphorae“, in: Bezeczky, ed. 2019, 41-46.

- Boltin-Tome, E. (1976): “Žigi na rimskih opekah iz depoja Pomorskega muzeja ‘Sergeja Mašera‘ Piran“, Arheološki vestnik, 25, 225-232.

- Boltin-Tome, E. (1979): “Slovenska Istra v antiki in njen gospodarski vzpon“, in: Mikeln, ed. 1979, 41-61.

- Boltin-Tome, E. (1991): “Arheološke najdbe na kopnem in na morskem dnu v Viližanu in Simonovem zalivu v Izoli“, Annales (HSS),1, 51-58.

- Boltin-Tome, E. and Karinja, S. (2000): “Grubelce in Sečoveljska dolina v zgodnjerimskem času“, Annales (HSS), 10, 481-510.

- Carre, M.-B. and Pesavento Mattioli, S. (2003): “Anfore e commerci nell’Adriatico”, in: Lenzi, ed. 2003, 268-285.

- Chiabà, M., Maggi, P. and Magrini, C., ed. (2007): Le Valli del Natisone e dell‘Isonzo tra Centroeuropa e Adriatico, Rome.

- Demougin, S. and Scheid, J., ed. (2012): Colons et colonies dans le monde romain, Collection de l‘École française de Rome 456, Rome.

- Djurić, B., Gale, L., Lozić, E. and Rižnar, I. (2018): “On the edge of the known. The quarry landscape at Podpeč (Na robu znanega. Kamnolomska krajina v Podpeči)“, in: Janežič et al., ed. 2018, 77-87.

- Djurić, B. and Rižnar, I. (2017): “Kamen Emone / The rocks for Emona“, in: Vičič & Županek, ed. 2017, 121-144.

- Ferle, M., ed. (2014): Emona: mesto v imperiju / Emona: a City of the Empire, Ljubljana.

- Gaspari, A. (1998-1999): “Römische Schmiedewerkstätten auf dem Hügel Ulaka in Innerkrain, Slowenien“, Archaeologia Austriaca, 82-83, 519-523.

- Gaspari, A. (2010): ‘Apud horridas gentis…‘. Začetki rimskega mesta Colonia Iulia Emona / Beginnings of the Roman Town of Colonia Iulia Emona, Ljubljana.

- Gaspari, A. (2014): Emona, Ljubljana.

- Gaspari, A. (2020): “Ulaka“, in: Horvat et al., ed. 2020, 141-171.

- Gaspari, A. and Erič, M., ed. (2012): Potopljena preteklost. Arheologija vodnih okolij in raziskovanje podvodne kulturne dediščine v Sloveniji, Ljubljana.

- Gaspari, A., Vidrih Perko, V., Štrajhar, M. and Lazar, I. (2007): “Antični pristaniški kompleks v Fizinah pri Portorožu–zaščitne raziskave leta 1998 / The Roman port complex at Fizine near Portorož–rescue excavations in 1998“, Arheološki vestnik, 58, 167-218.

- Hofman, B. and Trenz, A. (2006): “Koper – arheološko najdišče Pri Angelu“, Varstvo spomenikov, 42, 66-67.

- Horvat, J. (1997): Sermin. Prazgodovinska in zgodnjerimska naselbina v severozahodni Istri / Sermin. A Prehistoric and Early Roman Settlement in Northwestern Istria, Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 3, Ljubljana.

- Horvat, J. (1999): “Roman Provincial Archaeology in Slovenia Following the Year 1965: Settlement and Small Finds”, Arheološki vestnik, 50, 215-257.

- Horvat, J. and Sagadin, M. (2017): “Emonsko podeželje / Emona‘s contryside“, in: Vičič & Županek, ed. 2017, 201-223.

- Horvat, J., Lazar, I. and Gaspari, A., ed. (2020): Manjše rimske naselbine na slovenskem prostoru / Minor Roman settlements in Slovenia, Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 40, Ljubljana.

- Istenič, J. (1994): “The ‘Emona‘ Glass Beakers“, Arheološki vestnik, 45, 95-98.

- Istenič J. and Plesničar-Gec, L. (2001): “A pottery kiln at Emona“, RCRF Acta, 37, 141-146.

- Istenič, J., Daszkiewicz, M. and Schneider, G. (2003): “Local production of pottery and clay lamps at Emona (Italia, Regio X)“, RCRF Acta, 38, 83-91.

- Istenič, J. and Šmit, Ž. (2012): “A raw glass chunk from the vicinity of Nauportus (Vrhnika)“, in: Lazar & Županek, ed. 2012, 301-309.

- Janežič, M., Nadbath, B., Mulh, T. and Žižek, I., ed. (2018): Nova odkritja med Alpami in Črnim morjem /New Discoveries Between the Alps and the Black Sea, Monografije CPA 6, Ljubljana.

- Korošec, J. and Stare, F. (1950): “Začasno poročilo o arheoloških izkopavanjih v Ljubljani“, Arheološka poročila, Dela 1 SAZU 3, 7-37.

- Kramar, S., Tratnik, V., Hrovatin, I.M., Mladenovič, A., Pristacz, H. and Rogan Šmuc, N. (2015a): “Mineralogical and Chemical Characterization of Roman Slag from the Archaeological Site of Castra (Ajdovščina, Slovenia)“, Archaeometry, 57/4, 704-719.

- Kramar, S., Lux, J., Pristacz, H., Mirtič, B. and Rogan-Šmuc, N. (2015b): “Mineralogical and geochemical characterization of Roman slag from the archaeological site near Mošnje (Slovenia)“, Materiali in tehnologije / Materials and technology, 49.3, 343-348.

- Lavrič, M. and Bricelj, M. (2018): “Sledi metalurško-kovaške dejavnosti na najdišču Polje pri Vodicah (Traces of Metallurgical-Forging Activities at the Polje pri Vodicah Archaeological Site)“, in: Janežič et al., ed. 2018, 235-243.

- Lazar, I. (2003): Rimsko steklo Slovenije / The Roman Glass of Slovenia, Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 7, Ljubljana.

- Lazar, I. and Županek, B., ed. (2012): Emona med Akvilejo in Panonijo / Emona between Aquileia and Pannonia, Koper.

- Lenzi, F., ed. (2003): L’Archeologia dell’Adriatico dalla Preistoria al Medioevo, Bologna.

- Lipovac Vrkljan, G., Radić Rossi, I. and Šiljeg, B., ed. (2011): Rimske keramičarske i staklarske radionice: proizvodnja i trgovina na jadranskom prostoru. Zbornik I. međunarodnog arheološkog kolokvija, Crikvenica.

- Lipovac Vrkljan, G., Šiljeg, B., Ožanić Roguljić, I. and Konestra, A., ed. (2014): Rimske keramičarske i staklarske radionice: proizvodnja i trgovina na jadranskom prostoru. Zbornik II. međunarodnog arheološkog kolokvija, Zbornik Instituta za arheologiju 2, Zagreb-Crikvenica.

- Lozić, E. (2009): “Roman stonemasonry workshops in the Ig area / Rimske klesarske delavnice na Ižanskem“, Arheološki vestnik, 60, 207-221.

- Maggi, P. and Marion, Y. (2011): “Le produzioni di anfore e di terra sigillata a Loron e la loro diffusione“, in: Lipovac Vrkljan et al., ed. 2011, 176-187.

- Maselli Scotti, F., ed. (1997): Il Civico Museo Archeologico di Muggia, Trieste.

- Matijašić, R. (1998): Gospodarstvo antičke Istre: arheološki ostaci kao izvori za poznavanje društveno gospodarskih odnosa u Istri u antici (I. st. pr. Kr.–III. st. posl. Kr.), Povijest Istre 4, Pula.

- Marion, Y. and Starac, A. (2001): “Les Amphores“, in: Tassaux et al., ed. 2001, 97-125.

- Meterc, J. (1992): “Rodine“, Varstvo spomenikov, 34, 294.

- Mikeln, T., ed. (1979): Slovensko morje in zaledje, Zbornik za humanistične družboslovne in naravoslovne raziskave 2.3, Koper.

- Mušič, B. (1999): “Geophysical prospecting in Slovenia: an overview with some observations related to the natural environment“, Arheološki vestnik, 50, 349-405.

- Mušič, B. (2001): “An evaluation of the potential of geophysical prospections in difficult environments“, in: Slapšak, ed. 2001, 127-144.

- Pesavento Mattioli, S. and Carre, M.-B., ed. (2009): Olio e pesce in epoca romana. Produzione e commercio nelle regioni dell‘Alto Adriatico, Atti del Convegno, Padova, 16 febbraio 2007, Antenor Quaderni 15, Rome.

- Plesničar-Gec, L. (1976): “Steklene zajemalke iz severnega emonskega grobišča (Glass ladles from the northern cemetery of Emona)“, Arheološki vestnik, 25, 35-37.

- Plesničar-Gec, L. (1980-1981): “The production of glass at Emona“, Archaeologia Iugoslavica, 20-21, 136-142.

- Plestenjak, A. (2020): “Blagovica“, in: Horvat et al., ed. 2020, 231-247.

- Sagadin, M. (1982): “Bistrica pri Tržiču“, Varstvo spomenikov, 24, 165-168.

- Sagadin, M. (1984): “Antična stavba pri Bistrici pri Tržiču (The Roman building at Bistrica near Tržič)“, Arheološki vestnik, 35, 169-184.

- Sagadin, M. (1995a): “Mengeš v antiki (Mengeš in the Roman Period)“, Arheološki vestnik, 46, 217-245.

- Sagadin, M. (1995b): “Poselitvena slika rimskega podeželja na Gorenjskem“, in: Kranjski zbornik 1995, Kranj, 13-22.

- Schmid, W. (1913): “Emona“, Jahrbuch für Altertumskunde, 7, 61-188.

- Slapšak, B., ed. (2001): COST Action G2, Ancient landscapes and rural structures, Luxembourg.

- Slapšak, B. (2014): “Na sledi urbanega: poti do prve izkušnje mesta v prostoru Ljubljane / Unravelling the Townscape: Tracing the First Urban Experience on the Location of the Present-day Ljubljana“, in: Ferle, ed. 2014, 17-40.

- Stokin, M. (1992): “Naselbinski ostanki iz 1. st. pr. n. št. v Fornačah pri Piranu (Settlement remains from the first century B.C. at Fornače near Piran)“, Arheološki vestnik, 43, 79-92.

- Stokin, M. and Karinja, S. (2004): “Rana romanizacija i trgovina u sjeverozapadnoj Istri s naglaskom na materijalnu kulturu“, Histria Antiqua, 12, 45-54.

- Stokin, M. and Zanier, K. (2011): Simonov zaliv, San Simone, Vestnik 23,Ljubljana.

- Stokin, M., Gaspari, A., Karinja, S. and Erič, M. (2008): “Archaeological research of maritime infrastructure of Roman settlements on the Slovenian coast of Istria (1993-2007)“, in: Auriemma & Karinja, ed. 2008, 56-74.

- Šašel Kos, M. (2002): “The boundary stone between Aquileia and Emona”, Arheološki vestnik, 53, 373-382.

- Šašel Kos, M. (2012): “Colonia Iulia Emona – the genesis of the Roman city“, Arheološki vestnik,63, 79-104.

- Šribar, V. (1976): “Nekatere geomorfološke spremembe pri Izoli, dokumentirane z arheološkimi najdbami / Some archaeological relics and geomorphological changes at Izola”, Geologija, 10, 271-277.

- Tassaux, F. (2001): “Production et diffusion des amphores à huile istriennes“, in: Strutture portuali e rotte marittime nell’Adriatico di età romana, Collection de l’École française de Rome 280-Antichità Altoadriatiche46, Trieste-Rome, 501-543.

- Tomažinčič, Š. and Josipović, D. (2020): “Šmartno pri Cerkljah“, in: Horvat et al., ed. 2020, 213-229.

- Tassaux, F., Matijašić, R. and Kovačić, V., ed. (2001): Loron (Croatie). Un grand centre de production d’amphores à huile istriennes (Ier – IVe s. p.C.), Bordeaux.

- Tratnik, V. and Žerjal, T. (2017): “Ajdovščina (Castra) – poselitev zunaj obzidja / Ajdovščina (Castra) – the extra muros settlement“, Arheološki vestnik, 68, 245-294.

- Valič, A. and Petru, S. (1964-1965): “Antični stavbni kompleks na Rodinah (Complexe de construction antiques à Rodine)“, Arheološki vestnik, 15-16, 321-337.

- Vičič, B. (2002): “Zgodnjerimsko naselje pod Grajskim gričem v Ljubljani. Gornji trg 3 (Frührömische Siedlung unter dem Schloßberg in Ljubljana. Gornji trg 3)“, Arheološki vestnik, 53, 193-221.

- Vičič, B. and Županek, B., ed. (2017): Emona MM. Urbanizacija prostora – nastanek mesta / Urbanisation of space – beginning of a town, Ljubljana.

- Vidrih Perko, V. (1997): “Rimskodobna keramika z Ajdovščine pri Rodiku (Roman Pottery from Ajdovščina near Rodik)“, Arheološki vestnik, 48, 341-358.

- Vidrih Perko, V. and Žbona Trkman, B. (2003–2004): “Trgovina in gospodarstvo v Vipavski dolini in Goriških Brdih v rimski dobi. Interpretacija na podlagi najdišč Loke, Neblo, Bilje in Ajdovščina“, Goriški letnik, 30-31, 17-72.

- Vidrih Perko, V. and Žbona Trkman, B. (2004): “Aspetti ambientali e risorse naturali nell‘indagine archeologica: il caso della valle del Vipacco e i suoi rapporti con l‘economia aquileiese“, in: Progetto Durrës, Atti del secondo e del terzo incontro scientifico, Villa Manin di Passariano-Udine-Parma, 27-29 marzo 2003; Durrës, 22 giugno 2004, Antichità altoadriatiche 58, Trieste, 23-42.

- Vidrih Perko, V. and Župančič, M. (2011): “Local brick and amphorae production in western Slovenia / Lokalna proizvodnja opeke i amfora u zapadnoj Sloveniji“, in: Lipovac Vrkljan et al., ed. 2011, 151-163.

- Zaccaria, C. (1992): “Regio X. Venetia et Histria. Ager Tergestinus et Tergesti adtributus“, in: Supplementa Italica, n.s. 10, Rome, 139-283.

- Zaccaria, C., ed. (1993): I laterizi di età romana nell’area Nordadriatica, Cataloghi e monografie archeologiche dei Civici Musei di Udine 3, Rome.

- Zaccaria, C. (2007a): “Tra Natisone e Isonzo. Aspetti amministrativi in età romana“, in: Chiabà et al., ed. 2007, 129-144.

- Zaccaria, C. (2007b): “Attività e produzioni artigianali ad Aquileia. Bilancio della ricerca“, in: Aquileia dalle origini alla costituzione del ducato longobardo. Territorio, economia, società, 1, Antichità Altoadriatiche 65, Trieste, 393-438.

- Zaccaria, C. (2012): “Un nuovo duoviro della Colonia Romana di Tergeste e la produzione di olio nell‘Istria settentrionale“, in: Demougin & Scheid, ed. 2012, 107-121.

- Zaccaria, C. (2015): “Tergestini nell’impero romano: affari e carriere. La testimonianza delle iscrizioni”, Archeografo triestino, 123 (s. 4, vol. 75), 283-308.

- Zaccaria, C. and Župančič, M. (1993): “I bolli laterizi del territorio di Tergeste romana”, in: Zaccaria, ed. 1993, 135-180.

- Žbona Trkman, B. (1993): “I bolli laterizi dell’Isontino: stato delle ricerche”, in: Zaccaria, ed. 1993, 187-196.

- Žerjal, T. (2011): “Ceramic production in northern Istria and villa rustica at Školarice near Koper (Slovenija) / Keramičarska proizvodnja u sjevernoj Istri i u rustičnoj vili u Školaricama kraj Kopra (Slovenija)“, in: Lipovac Vrkljan et al., ed. 2011, 139-146.

- Žerjal, T. (2014): “Roman tegulae in northern Istria”, in: Lipovac Vrkljan et al., ed. 2014, 219-240.

- Žerjal, T. (2018): “Keramični skupek vile rustike Polje pri Vodicah (Ceramic Assemblages from the Roman Site Polje pri Vodicah)”, in: Janežič et al., ed. 2018, 281-301.

- Žerjal, T. and Poglajen, S. (2012): “Rimsko podeželje Slovenske Istre: nova spoznanja in stara vprašanja”, in: Gaspari & Erič, ed. 2012, 109-120.

Notes

- The maps and figures are the work of Mateja Belak and Dragotin Valoh (ZRC SAZU, Inštitut za arheologijo). The text in English was amended by Andreja Maver. The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Slovenian Research Agency as part of the P6-0064 research programme (Archaeological research) and P6-0283 research programme (Movable cultural heritage: archaeological and archaeometric research).

- Carso in Italian, Karst in German.

- Horvat 1999; Zaccaria 1992; Id. 2007a; Šašel Kos 2002.

- Gaspari 2010; Šašel Kos 2012; Slapšak 2014.

- Istenič & Plesničar-Gec 2001.

- Istenič et al. 2003, 83.

- Istenič et al. 2003.

- At a distance of 7-12 km from Emona; Horvat & Sagadin 2017, 215-216.

- Vičič 2002.

- Schmid 1913.

- Schmid 1913, 108-109, fig. 37, Pl. 6.

- Schmid 1913, 112-113, fig. 41, Pl. 6.

- Schmid 1913, 141, 144, fig. 54, Pl. 11.

- Schmid 1913, 145, fig. 58, Pl. 11.

- Gaspari 2014, 190, fig. 211.

- Korošec & Stare 1950, 20, fig. 8.

- Schmid 1913, 171-177, fig. 79, Pl. 5. The objects from the hoard are lost.

- Schmid 1913, 177-179, figs. 80-81, Pl. 15. The bars are lost.

- Plesničar-Gec 1980-1981.

- Lazar 2003, 216-217.

- Plesničar-Gec 1976; Ead. 1980-1981; Istenič 1994; Lazar 2003, 94-97, 123-125, Forms 3.4.1, 4.2.

- Istenič & Šmid 2012.

- Djurić & Rižnar 2017.

- Lozić 2009; Djurić & Rižnar 2017, 129-134; Djurić et al. 2018.

- Stokin & Karinja 2004; Žerjal & Poglajen 2012; Stokin & Zanier 2011.

- Žerjal 2011; Ead. 2014; Vidrih Perko & Župančič 2011.

- Boltin-Tome 1979, 57.

- Stokin & Karinja 2004, 49.

- Viližan: Šribar 1976; Boltin-Tome 1976, 57; Ead. 1991. Fornače: Stokin 1992; Horvat 1997, 73-74, 120-121. Fizine: Gaspari et al. 2007.

- Boltin-Tome 1979, 57.

- Excavations by A. Puschi. Boltin-Tome & Karinja 2000; Vidrih Perko & Župančič 2011, 155, 160.

- Maselli Scotti 1997, 60-61, 63.

- Cf. Marion & Starac 2001, 116-117: “Col à entonnoir”; Bezeczky 1998, 7-9: Emperor‘s amphorae; Carre & Pesavento Mattioli 2003, 463: Dressel 6B di terza fase istriane.

- Bezeczky 1998, 9-10: Fažana I and II; Marion & Starac 2001, 117-119: « d’époque tardive »; Carre & Pesavento Mattioli 2003, 467-468: anfore Dr. 6B di quarta fase istriana; Maggi & Marion 2011; Pesavento Mattioli & Carre, eds. 2009.

- Hofman & Trenz 2006; Vidrih Perko & Župančič 2011, 155-157.

- Boltin-Tome & Karinja 2000; Vidrih Perko & Župančič 2011, 154-155.

- Carre & Pesavento Mattioli 2003; Pesavento Mattioli & Carre, ed. 2009; Maggi & Marion 2011; Bezeczky 2019, 42-45.

- Matijašić 1998, 262-268; Carre & Pesavento Mattioli 2003, 277; Stokin et al. 2008.

- Žerjal 2011.

- Zaccaria & Župančič 1993; Žerjal 2014.

- Žerjal 2011; Vidrih Perko & Župančič 2011.

- Zaccaria & Župančič 1993; Tassaux et al., ed. 2001; Zaccaria 2012; Zaccaria 2015; Žerjal 2014.

- Žerjal 2011; Ead. 2014; Zaccaria 2012.

- Žerjal 2011; Ead. 2014; Vidrih Perko & Župančič 2011.

- Vidrih Perko & Žbona Trkman 2003-2004; Iid. 2004; Zaccaria 2007b.

- Vidrih Perko & Žbona Trkman 2003-2004; Iid. 2004; Vidrih Perko & Župančič 2011, 158-159.

- Žbona Trkman 1993.

- Vidrih Perko & Žbona Trkman 2003-2004; Iid. 2004; Vidrih Perko & Župančič 2011, 157-158.

- Tratnik & Žerjal 2017, 252, 263, 281, 283; Kramar et al. 2015a.

- Plestenjak 2020.

- Sagadin 1995a, 224-230, Pls. 9: 3; 11: 3.

- Lavrič & Bricelj 2018; Žerjal 2018.

- Sagadin 1995b, 16.

- Kramar et al. 2015b.

- Sagadin 1984; slag: Sagadin 1982, 168.

- Valič & Petru 1964-1965; Meterc 1992; Horvat & Sagadin 2017, 212.

- Tomažinčič & Josipović 2020, 226-227.

- Gaspari 1998-1999; Id. 2020.

- Vidrih Perko 1997.

- Mušič 1999, 356-370; Id. 2001, 129-136.

- Mušič 1999, 370-376; Id. 2001, 136-139.

- Gaspari 2020, 160-161.

- Gaspari 2020, 163-164.

- Unpublished.