A further contribution to be included in the conference volume “Crossing the Alps: Early Urbanism between Northern Italy and Central Europe (900-400 BC)”, 29-30 March 2019 in Milan, concerns the obvious aspects of centralization and hierarchy on Mount Ipf. See Krause 2020b.

Theme

The intent of the following contribution is to present the many and varied settlement structures and fortifications in their spatial context as revealed over the past 20 years of new and intensive research on Mount Ipf.

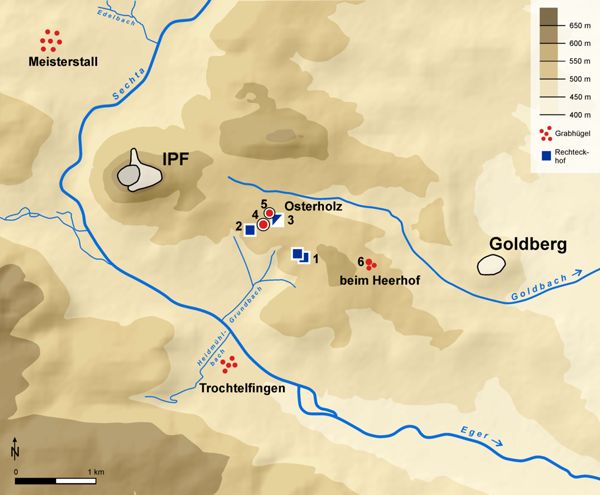

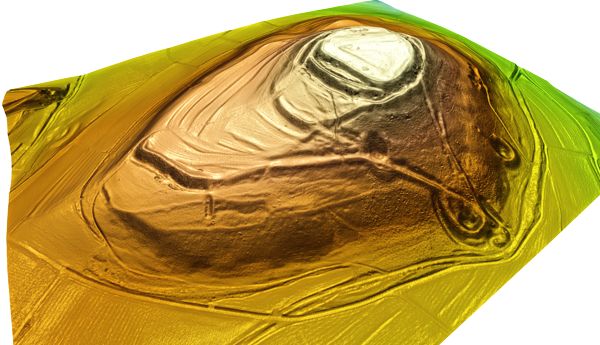

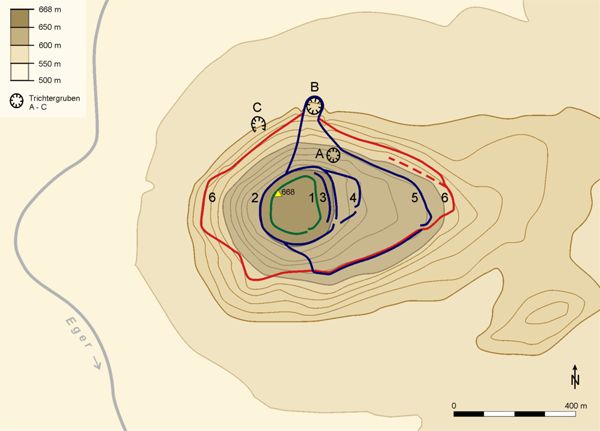

The elevation itself can be divided into two distinct parts, topographically as well as substantively: a densely built settlement on the upper plateau – the “upper fortress” (Oberburg) – and a less built-up settlement with large rectangular enclosures on the lower plateau – the “lower fortress” (Unterburg). The differences and variations in contexts and structures that have been identified form the basis for all further research interpretations. Namely, recent investigations have convincingly shown that the strongly fortified complex upon Mount Ipf held an extraordinary position ever since the Late Bronze Age and Urnfield culture, specifically as a centre of power on the western periphery of the Nördlinger Ries (Fig. 1).1

The significance of the fortifications on Mount Ipf and in its surroundings has gained more precise contours through recent research on the Early Iron Age.2 The Ipf was part of the sphere of early Celtic “princely seats” in central Europe for at least 100 years and maintained direct relations via the eastern Alps with northern Italy and Greek-influenced regions of the Etruscans in the Po Valley and the head of the Adriatic. Today this is attested foremost by a large number of high-quality imported goods, which came to light in the rectangular enclosed compounds (Rechteckhöfe) near the hamlet Osterholz – dated to the late Hallstatt and early La Tène period – and also on the upper plateau of Mount Ipf itself. These finds can be associated with the high social rank of the inhabitants.

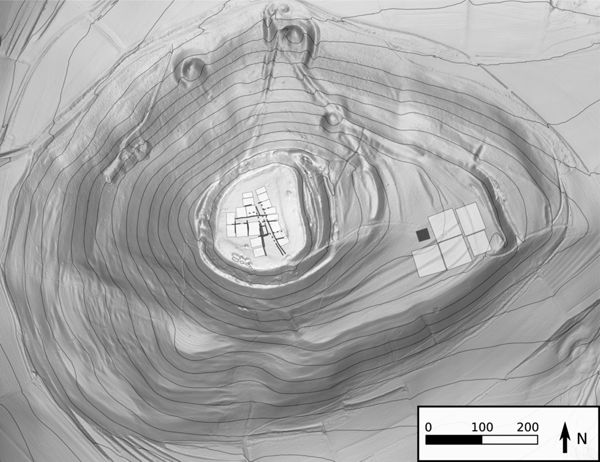

One of the new discoveries made since 2000 is an exceptional area situated near the present-day hamlet of Osterholz (borough of Kirchheim am Ries), located at the foot of Mount Ipf and halfway between the Ipf and the Goldberg, on a ridge above the Ries plain (Fig. 2). There, in the course of prospection by means of aerial imagery and successive large-scale geomagnetic measurements, two rectangular enclosed compounds (Rechteckhöfe) were discerned in Gewann Zaunäcker and Bugfeld. They were subsequently excavated between 2000 and 2006. A large burial mound was additionally discovered (Mound 1, 64 m in diameter), until then not recognized as such, which is still preserved today in the form of an undulation in the terrain measuring more than 100 m.3

Further, a second, smaller and completely ablated burial mound (Mound 2, 22 m in diameter) in its vicinity is visible in geomagnetic images. Excavation in 2003 revealed a cremation burial of a lady in a wooden grave chamber, richly furnished with tableware of a quality that is unusual for the region. This burial can be dated to the time of transition from Hallstatt C to Hallstatt D1 (ca. 620 BC).4 This means that this burial was possibly associated with the hillfort settlement on the Goldberg and – further – might have been of a member of the founding dynasty: an ancestress of the rulers seated upon Mount Ipf.

Based on these recent discoveries, today we are able to circumscribe an outer area at the foot of Mount Ipf, in which enclosed rectangular compounds as well as monumental burial mounds are located (Fig. 2). Yet this area may hardly be interpreted as an “outer settlement”, as in the case – for example – of the Heuneburg on the upper River Danube.5 It is far more likely that it should be interpreted as a section exclusively for the social elite, for their residences in the form of enclosed rectangular compounds, and for large burial mounds. Results of excavations at the rectangular compound in Gewann Bugholz yielded unusual find contexts, which allow a cultic character to be envisioned.6 This in turn leads to the question of a cultic-religious concept for the princely seat on Mount Ipf, too.

These new discoveries demonstrate very impressively the importance of knowledge about the neighbouring surroundings for a better understanding of the princely seat upon Mount Ipf. Accordingly, excavations were conducted at the foot of the Ipf, in the aforementioned rectangular compounds, which date to late Hallstatt and early La Tène times. The sites are distinguished by exceptional finds of glass, amber, metal and ceramics, the latter including Attic pottery from Greece and wine amphorae from Italy. In view of these findings, the sites can be recognized as estates and residences of the princely clan of the Ipf. In association with large burial mounds the inhabitants can be viewed as the social elite of their time. The appearance of imported goods from the south and the construction of monumental tumuli with richly furnished burials are considered evidence of changes in hierarchical and economic foundations.

Indeed, following Wolfgang Kimmig’s concept of princely seats, exceptional goods from the south and large tumuli over luxurious burials still hold true as essential elements for the definition of a group of topographical as well as socially prominent strongholds, which we call “princely seats”.7

The fortress on Mount Ipf surely served to a great degree as a place of representation and display of prestige and rank, and – not least – a mighty fortification, visible from afar (Fig. 1).8

Prior to the discoveries made since 2000, the state of archaeology and history about Mount Ipf relied mainly on findings and knowledge gained from excavations by Friedrich Hertlein in 1907 and 1908.9 His results were expanded through an abundance of surface finds and excavations in 2004–2005 on the upper plateau. They attest to human occupation on Mount Ipf ever since Neolithic times, in particular extensive settlement of the upper plateau by the Urnfield culture.10 The body fragment of a small black-polished Attic drinking bowl, discovered in 1960, was the first evidence of Mediterranean imports. Until then little research had been done on the large burial mounds with luxurious furnishings, which Wolfgang Kimmig held to be a typical criterion for fortresses of early Celtic elites.11 In general, very little was known about the settlement landscape of the Early Iron Age on the western periphery of the Nördlinger Ries and about the Ipf and its environs (Fig. 3). Only the nearby Goldberg with its fortified settlement of the Hallstatt period had gained renown as one of the “great sites” in the pre- and early history of southern Germany through the early archaeological investigations by Gerhard Bersu.12

Spatial organization in relation to the surroundings

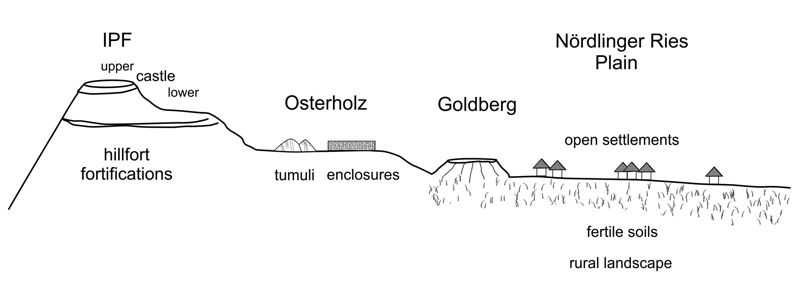

An important question stood at the centre of recent research activities: What was the connection and relationship between the two hillfort sites of the Ipf and Goldberg, which lie only 4.5 km apart as the crow flies (Fig. 2). And with that, the question as to the social structures and the hierarchies of the social elites. Gerhard Bersu’s approach in 1930 was still, according to the model, that a “royal castle” was located on the topographically prominent Mount Ipf (Fig. 4), which was one of a number of smaller “princely forts”, such as the castle upon the Goldberg. Today we know that in the course of the rise of the Ipf and the construction of rectangular compounds and large burial tumuli near Osterholz, the Goldberg declined greatly in significance. During the late Hallstatt phase (620–580/50 BC) there was a hiatus in settlement. Much suggests that during that time the seat of power shifted from the Goldberg to Mount Ipf. Consequently, all of the settlement activities shifted to Mount Ipf, too. According to Bersu, apparently the governance and dominion of the castle lord were relocated from the Goldberg to the Ipf13.

Fortification walls

During the late Hallstatt phase Ha D 2/3 (second half of the sixth century BC) a fortification was built around the Ipf, which was 2.4 km long and encompassed 30 hectares, including the steep slopes. Hence, the space within the fortified hill was expanded considerably (Figs 5; 6).

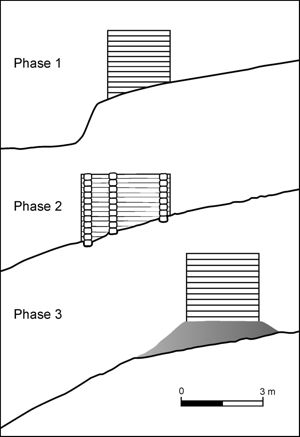

Recent excavations in 2016–2019 have brought forth further important information concerning the reconstruction of the building history of the fortifications. In view of the find contexts, three building phases can be determined – with reservations – including a wooden-box-wall construction (Fig. 6).

The best parallels to this construction can be found in building phase IVc of the late Hallstatt fortress of the Heuneburg.14 Egon Gersbach suggested that small ditches corresponded to the reconstruction of a double-row, wooden-box construction, erected upon foundation beams. The wooden-box-wall of the Heuneburg is 4.8 m wide. A comparable construction is also imaginable for the Ipf: there the width of the wooden-boxes cut into the dip of the slopes would have been 3.5 m.15 Based on the finds at hand, the building phases can be dated to the late Hallstatt period.

Fortification 6 is 2.4 km in length, and it runs around the mount mid-way way up (Fig. 5).

Moreover, F. Hertlein’s results and those of recent investigations have shown that there was already a large settlement and fortification on the summit plateau during the Late Bronze Age Urnfield culture. Geomagnetic investigations and targeted excavations have confirmed a densely built settlement on the upper plateau (Fig. 7).

By contrast, on the lower plateau a palisade construction enclosing at most up to 50 x 50 m was revealed, which is similar to a rectangular compound. Excavations uncovered a great number of postholes, which however did not indicate any contiguous structure, at least not according to the present state of research. Thus, questions pertaining to the building history of the rectangular compounds there must remain open.

At the end of the Hallstatt period the outer fortification 6 (Fig. 5) was abandoned and cleared away. The early La Tène fortification with a stone-and-post-slot wall (Pfostenschlitzmauer) was erected during the first half of the fifth century BC (Figs 5, 5). It was much smaller in area and today still encompasses only 11.5 hectares. Through this building activity the two water sources – A and B – at the northern foot of the mountain (Fig. 5A, B) in fortification 5 were brought within the wall and served as important water storage facilities and cisterns. The new construction of the 1.4 m-long, massive fortification 5 with Pfostenschlitzmauer signifies that, in early La Tène times, a drastic reduction of the fortified area took place (Fig. 5) compared to the late Hallstatt fortification that was more than twice the size. Nonetheless, this measure was not a reduction in the sense of a decline in or loss of importance; instead, the erection of the Pfostenschlitzmauer came at a time when – judging by the amount of Mediterranean imports and other evidence – the early Celtic princely seat was thriving at the beginning of the early La Tène A, in the fifth century BC.16

Although the original fortified surface area was considerably reduced in the course of the aforementioned dismantling of defensive wall 6, the stone-and-post-slot wall (no. 5) was of a more imposing architecture and the effect of its external appearance greatly amplified (Fig. 8).17 This restructuring is extremely substantial, so we view this undertaking not as a sign of reduction or decline, but rather as a declaration of strength and a show of authority at the height of the political and economic prosperity of Mount Ipf and its elites, a regional centre of power with far-reaching relations and connections.

The structural differences in building activities and the changes in size, area and architecture of the fortifications have led to various interpretations, which have been published elsewhere,18 and which are of fundamental importance for a synthetic assessment of cultural relations at Mount Ipf and in its environs. These aspects include (1) territory, (2) spatial and architectural organization, and (3) hierarchy.

Territory

Within the framework of our investigations we also pursued the aspect of a possible sphere of influence or territory affected by Mount Ipf (Fig. 9).19 We distinguish between a “centre” comprising Mount Ipf and its immediate surroundings, with rectangular compounds near Osterholz and the Goldberg, as well as an associated area that possibly lies within the natural borders of the Nördlinger Ries. If we observe the immediate vicinity of the Ipf with the flat plain of the Nördlinger Ries and its peripheral hilly landscapes, and then consider the structural foundations, the following aspects become recognizable. The Nördlinger Ries with its fertile soils and developed agriculture was one of the outstanding settlement landscapes in southern Germany during the Bronze Age and Iron Age.20 Today we know that since the Late Bronze Age intensive settlement took place there, accompanied by several smaller and larger fortifications in the bordering hills on the edge of the Ries plain. The settlements grew to considerable density during the earlier Iron Age. The neighbourhood of the hilltop sites of the Ipf and Goldberg displays a remarkable number of settlements, cemeteries and burial mounds, which date to the Hallstatt and La Tène periods, that is, the Early and Late Iron Age (Fig. 3).21 As described above, substantial changes at the end of the Late Bronze Age Urnfield culture took place in the fortified hill settlements, changes that ultimately led to a difference in importance and a shift in power from the Goldberg to Mount Ipf.

The rectangular compounds near Osterholz, between the Goldberg and Mount Ipf, held a special position in view of the buildings and building methods and the unusual finds such as Mediterranean goods, among others. Therefore, they are viewed as country estates or residences of elite groups among the Ipf population. In this way a hierarchy in society formed among the various settlements in the topography of the western periphery of the Nördlinger Ries (Fig. 10).

This includes:

- the Ries basin: with rural settlement structures of the Late Bronze Age (Urnfield culture) and the Late Iron Age (Hallstatt C/D and La Tène A);

- the Goldberg: with a hamlet structure and with a delimited area for the elite (Hallstatt C/D 1-2);

- two enclosures and two large burial mounds at the foot of Mount Ipf, near Osterholz.

In principle the settlement forms on the Goldberg and Mount Ipf can be explained as rural structures. During the earlier Hallstatt period there was a delimited area with unusual structures on the Goldberg; structures that did not compare with rustic structures in the countryside.22 The reconstructed, comparably dense building on the upper fortified plateau of Mount Ipf (Fig. 7) deviates from the usual rural structures and can be classified as the dense building of an organized population, in the sense of an agglomeration and organized housing.23

Questions remain as to how far that population’s influence reached beyond the settlements into areas east of the Ries plain and the cultural sphere of the Franconian Alb. This has led to interesting results in the mapping of ceramic styles.24 Specifically, the Ipf lies at the centre of the distribution area of the so-called Ostalbkeramik of the Hallstatt period. The spread of this pottery could be used as a criterion to mark an original sphere of influence on the basis of material culture.25

Spatial organization

For the question of the spatial organization of the many and varied elements, the finds and find contexts revealed on Mount Ipf and in its environs, here I wish to resort to considerations and models proposed by E. Gringmuth-Dalmer in 1996 for a “complex centre with the following competences and characteristics”. They comprise the following features:26

- power, control

- defence

- supply and control of natural resources

- crafts, workshops

- commerce

- trade

- cult, religion

- architecture and structures on the fortified plateaus (upper fortress and lower fortress)

The topography of Mount Ipf itself is structured into two areas: a densely built settlement on the upper plateau, and a less built-up area with enclosures on the lower plateau.

Characteristics might be described as:

- mighty defences, visible from a great distance (Fig. 1), a demonstration of power and prestige;

- Mediterranean goods/imports, contact with the Mediterranean world for decades (more than one hundred years);

- large burial tumuli, for example, the “princely grave”, measuring 56 m in diameter;

- two enclosed rectangular compounds = residences of the elites in the population;

- favourable economic basis, good supply of quality meat and agricultural produce, animal husbandry, copper and iron metallurgy.

All in all the structures and building activities on Mount Ipf and in its surroundings correspond to the criteria and competences as well as the characteristic features of a complex centre, which we call a “princely seat”, a term based on its genesis in research history and in the sense of a terminus technicus.27 Nonetheless, unlike other such centres, above all the Heuneburg on the upper Danube,28 no evidence of proto-urban or urban structures has been discovered.

Hierarchy

The issues of social hierarchies and social elites were discussed at the conference in Milan in 2018 and published in the conference volume,29 so only a brief summary of the basic features on Mount Ipf that relate to this subject will be presented here.30

- prominent fortified hill settlement and large ramparts;

- differences in the dwellings and in the distribution pattern of Greek pottery found in the upper fortress as compared to those in the lower fortress;

- two enclosures at the foot of Mount Ipf, which display unusual structures and buildings as well as a remarkable material culture; i.e. they are residences of elites;

- presence of at least one large burial tumulus, of the “princely grave” (Fürstengrab) category;

- structured dwellings in various landscapes and different situations: they represent a hierarchy among settlements and types of settlements (open settlements, enclosed compounds, fortified hill settlement, see fig. 10);

- elites and elite networks were in control of the economy and power; they maintained close ties with the Mediterranean – with the Etruscans and Greek colonies;

- individuals or small groups of high rank/social standing, who had to prove their status as elites again and again;

- complex centres, or technically Fürstensitze.

Summary

Regarding the genesis of the hilltop settlement on Mount Ipf, at least two processes of concentration can be observed: one during the Late Bronze Age Urnfield Culture occupation, and one in the early Hallstatt period. These processes led, for example, to the abandoning of settlement and defences on the Hesselberg during the Late Bronze Age and on the Goldberg during the early Hallstatt period. From these processes the theory can be derived and thus proposed that what is manifested here is the concentration of political and economic power on Mount Ipf. Therefore, today we may assume that the early Celtic princely seat with its massive ramparts held the outstanding position as a centre in the Nördlinger Ries and the surrounding countryside. The extent to which this sphere of influence reached and how it should be defined are still topics of discussion.31

The concentration process in the Nördlinger Ries did not, however, lead to forms of urbanization, as was the case for example in the area of the Heuneburg on the upper Danube. Settlement dynamics and developments since the Late Bronze Age, as observed at the Goldberg and Ipf, are particularly informative and elucidative with reference to the Nördlinger Ries and its princely seats and power, from the standpoint of socio-economic and political power. The processes involved in changes in the settlement landscape – which we term “concentration processes” in an economic as well as a sociological and political sense – become quite clear when they derive from different interdisciplinary sources.

Synthesis

From this compilation of various aspects pertaining to the genesis and development of the princely seat on Mount Ipf and in its environs or core territory, the properties and particularities of this central site become distinct. Its protective function and representation of power become tangible through its prominent appearance in the surroundings and through its ramparts and fortifications. Craftmanship and acquisition of natural resources as important factors become apparent in the initial approach in research, for example, evidence of metallurgical activities as well as foreign ceramics (among others, wheel-made pottery and flasks with circle decoration). Closely associated with this are also commerce – trade and exchange – with the Mediterranean and the acquisition of corresponding goods such as wine and accompanying vessels, in addition to amber and metal, which were of special importance.

Advancements in agriculture are evident through improved use of the land. Social differentiations in settlement forms are evidenced by high-quality finds as well as by differences in food supply.

The find contexts of a large building and the aftermath of its abandonment as revealed in the rectangular compound in Osterholz-Bugfeld are indeed extraordinary. There we see evidence of a cultic structure and cultic activities, which in this form and considered together with the Glauberg enable a new cultic-religious concept to be recognized north of the Alps. Upon the abandonment of the ruling domain on the Goldberg, the (new?) elite people resided in the rectangular compounds at the foot of Mount Ipf and dominated the fortress upon Mount Ipf, which was visible from afar.

The hill and its mighty ramparts (figs 4 and 5) were an expression of their political and economic dominance, which – in view of the evidence – was not at all brief, but continued over a lengthy period of time, during the sixth and fifth centuries BC, i.e. more than one hundred years. The underlying structural form of society and governance, whether a segmented lineage system, a clientele policy, or a ranked society,32 cannot be discussed in further detail in this contribution. In any case, concerned here was a social elite and the leaders of that time, who are designated “princes” according to the criteria described above and who ruled from the princely seat on Mount Ipf.

References

- Bersu, G. (1930): “Der Goldberg bei Nördlingen und die moderne Siedlungsarchäologie”, in: Archäologisches Institut des Deutschen Reiches. Bericht über die Hundertjahrfeier 21-25. April 1929, 313-318.

- Bick, A. (2007): Die Latènezeit im Nördlinger Ries. Materialh. Bayer. Vorgesch., A 91,Kallmünz/Opf.

- Böhr, E. (2015): “Fragmente griechischer Keramik vom Ipf und aus seiner Umgebung”, in: Bonomi & Guggisberg, ed. 2015, 179-191.

- Bonomi, S. and Guggisberg, M.A., ed. (2015): Griechische Keramik nördlich von Etrurien: Mediterrane Importe und archäologischer Kontext. Int. Tagung Basel 14.–15. Oktober 2011, Wiesbaden.

- Brosseder, U. and Krause, R. (2014): “Hallstattzeitliche Großgrabhügel am Fürstensitz auf dem Ipf bei Osterholz, Gde. Kirchheim am Ries”, in: Krause, ed. 2014, 145-184.

- Eggert, M. K. H. (2007): “Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früheisenzeitlichen Mitteleuropa: Überlegungen zum ‘Fürstenphänomen’”, Fundber. Baden-Württemberg, 29, 255-302.

- Euler, D. and Krause, R. (2012): “Genèse et développement de la résidence princière sur le mont Ipf près de Bopfingen (Ostalbkreis, Bade-Wurtemberg) et de son territoire environnant dans le Nördlinger Ries au début de l’époque celtique”, in: Sievers & Schönfelder, ed. 2014, 29-56.

- Fischer, F. (2000): “Zum ‘Fürstensitz’ Heuneburg. In: W. Kimmig (Hrsg.), Importe und mediterrane Einflüsse auf der Heuneburg”, Heuneburgstudien XI = Röm.-Germ. Forsch., 59, 215-227.

- Fricke, F. and Krause, R. (2019): “Holzkästen am Hang? – Ausgrabungen in der äußeren Befestigung des Ipfs”, Arch. Ausgr. Bad.-Württ., 2017, 160-164.

- Fries, J. E. (2005): Die Hallstattzeit im Nördlinger Ries. Materialh. Bayer. Vorgesch. A 88, Kallmünz/Opf.

- Gersbach E. (1995): “Baubefunde der Periode IVc-IVa der Heuneburg”, Heuneburgstudien IX. Röm.-Germ. Forsch., 53, Mainz.

- Gringmuth-Dallmer, E. (1996): “Kulturlandschaftsmuster und Siedlungssysteme”, Siedlungsforschung. Archäologie-Geschichte-Geographie, 14, 7-31.

- Gyucha, A. (2019): “Population Aggregation and Early Urbanization from a Comparative Perspective”, in: Gyucha, ed. 2019, 1-35.

- Gyucha, A., ed. (2019): Coming Together. Comparative Approaches to Population Aggregation and Early Urbanization, New York.

- Hertlein F. (1911): Die vorgeschichtlichen Befestigungen auf dem Ipf. Blätter des Schwäb. Albvereins. XXIII. Jg, Nr. 2, 48 ff.

- Kimmig, W. (1969): “Zum Problem der späthallstattzeitlichen Adelssitze”, in: Festschrift P. Grimm, Siedlung, Burg und Stadt. Studien zu den Anfängen. Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, Schriften der Sektion Vor- und Frühgeschichte 25, 95-113.

- Knoll, D. (2020): “Der Ipf in der Bronzezeit”, in: Krause, ed. 2020.

- Krause, R. (2014): “Zum Stand der Forschungen auf dem Ipf und den Perspektiven aus dem Schwerpunktprogramm der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft 2004-2010”, in Krause, ed. 2014, 1-49.

- Krause, R., ed. (2014): Neue Forschungen zum frühkeltischen Fürstensitz auf dem Ipf, Frankfurter Archäologische Schriften 24, Bonn.

- Krause, R. (2015): “Mediterrane Funde am frühkeltischen Fürstensitz auf dem Ipf im Nördlinger Ries. Räumliche Verteilung und historische Interpretation”, in : Bonomi & Guggisberg, ed. 2015, 193-202.

- Krause, R. (2015): Der Ipf. Fürstensitz im Fokus der Archäologie, Stuttgart.

- Krause, R. (2018): “Die bronzezeitliche Burg auf dem Ipf – Neue Forschungen zum Burgenbau und Krieg in der Bronzezeit”, Dokumentationsband Rieser Kulturtage, XXI, 2016, 117-134.

- Krause, R. (2019): “The hillfort on Mount Ipf: A centre of power during the Bronze and Iron Ages in southern Germany”, in: Romankiewicz et al., ed. 2019, 55-64.

- Krause, R., ed. (2020): Archäologische Beiträge zur Bronze- und Eisenzeit auf dem Ipf, Frankfurter Archäologische Schriften 40, Bonn.

- Krause; R. (2020): “Centralisation Processes at the Fürstensitz (Princely Seat) on Mount Ipf in the Nördlinger Ries, Southern Germany”, in: Zamboni et al., ed. 2020, 319-332.

- Krause, R., Böhr, E. and Guggisberg, M. (2005): “Neue Forschungen zum frühkeltischen Fürstensitz auf dem Ipf bei Bopfingen, Ostalbkreis (Baden-Württemberg)”, Prähistorische Zeitschrift, 80, 190-235.

- Krause, R., Stobbe, A., Euler, D. and Fuhrmann, K. (2010): “Zur Genese und Entwicklung des frühkeltischen Fürstensitzes auf dem Ipf bei Bopfingen (Ostalbkreis, Baden-Württemberg) und seines territorialen Umlandes im Nördlinger Ries”, in: Krausse & Beilharz, ed. 2010, 169-207.

- Krause, R. and Fricke, F. (2020): “Befestigungen der Bronze- und Eisenzeit auf dem Ipf. Neue Ausgrabungen 2016–2019 am Fuß des Berges”, in: Krause, ed. 2020, 13-41.

- Krause, D., Kretschmer, I. Hansen, L. and Fernández-Götz, M. (2017): “Die Heuneburg – keltischer Fürstensitz an der oberen Donau”, Führer zu archäologischen Denkmälern in Baden-Württemberg, 28, Darmstadt.

- Krausse, D. and Beilharz, D., ed. (2010): “Fürstensitze” und Zentralorte der frühen Kelten. Abschlusskolloquium des DFG-Schwerpunktprogramms 1171 in Stuttgart, 12.–15. Oktober 2009. Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg, Band 120/1, Stuttgart.

- Kurz, S. (2010): Zur Genese und Entwicklung der Heuneburg in der späten Hallstattzeit, in: Krausse & Beilharz, ed. 2010, 239-256.

- Parzinger, H. (1998): “Der Goldberg. Die metallzeitliche Besiedlung”, Röm.-Germ. Forsch., 37.

- Romankiewicz, T., Fernandez-Götz, M., Lock, G. and Büchsenschütz, O., ed. (2019): Enclosing Space, Opening New Ground. Iron Age Studies from Scotland to Mainland Europe, Oxford,

- Schier, W. (2010): “Soziale und politische Strukturen der Hallstattzeit – ein Diskussionsbeitrag”, in: Krausse & Beilharz, ed. 2010, 375-405.

- Schussmann, M. (2012): “Siedlungshierarchien und Zentralisierungsprozesse in der Südlichen Frankenalb zwischen dem 9. und 4. Jh. v. Chr.”, Berliner Archäologische Forschungen, 11.

- Schussmann, M. (2014): “Hinter’m Horizont geht’s weiter – Überlegungen zum Einflussgebiet des ältereisenzeitlichen Zentralortes auf dem Ipf”, in: Krause, ed. 2014, 185-211.

- Sievers, S. and Schönfelder, M., ed. (2012): Die Frage der Protourbanisation in der Eisenzeit – La question de la proto-urbanisation à l‘âge du Fer, Akten des 34. internationalen Kolloquiums der AFEAF vom 13.–16. Mai 2010 in Aschaffenburg, Kolloquien zur Vor- u. Frühgeschichte 16, Bonn.

- Zamboni, L., Fernándes-Götz, M. et Metzner-Nebelsick, C., ed. (2020): Crossing the Alps: Early Urbanism between Northern Italy and Central Europe (900-400 BC). Proceedings of the International Conference in Milan, 29-30 March 2019, Leiden.

Notes

- Krause 2019; Knoll 2020.

- Krause et al. 2005, Krause et al. 2010, Krause (ed.) 2014, Krause (ed.) 2020a.

- Brosseder & Krause 2014, Abb. 1-3.

- Brosseder & Krause 2014, 153 f.

- Kurz 2010.

- Krause et al. 2010, 184 ff.

- Kimmig 1969; Fischer 2000.

- Krause 2020a, Krause 2020b.

- Hertlein 1911.

- Krause 2018; Knoll 2020.

- Kimmig 1969; see also Eggert 2007.

- Bersu 1930; Parzinger 1998; Krause 2015b.

- Krause 2015b, 72–74.

- Gersbach 1995, Abb. 3.

- Fricke & Krause 2019; Krause & Fricke 2020.

- Euler & Krause 2012, Fig. 9, 16, 17; Böhr 2015; Krause 2015a.

- Cf. Krause & Fricke 2020.

- Krause 2014; Krause 2015b; Krause 2019; Krause 2020b.

- The term “territory” or area is used here to designate a delimited space over which a claim to power exists and which is available as a resource (for example, food production). Cf. W. Schiefenhövel, Territorium. In: W. Hirschberg, Wörterbuch der Völkerkunde (Berlin 1999) 370.

- Fries 2005; Bick 2007.

- Fries 2005; Bick 2007; Krause 2015b.

- Parzinger 1998.

- Gyucha 2019.

- Schußmann 2012.

- Schußmann 2012; Schußmann 2014.

- Gringmuth-Dalmer 1996.

- See Fischer 2000; criticism in Eggert 2007.

- See the contribution by Dirk Krausse et al. in this volume. In addition Krausse et al. 2017; Krausse et al. 2020.

- Krause 2020b.

- See Euler & Krause 2012, Fig. 19.

- Cf. Schußmann 2014.

- Cf. Eggert 2007, 260 ff., Schier 2010; Krause 2019.