Introduction

The dhole (Cuon alpinus Pallas, 1811) is a social canid that is smaller than a wolf and is a habitat generalist. The species is currently distributed throughout India, China, SE Asia and Indonesia. No pronounced sexual dimorphism is observed in the species, except for the somewhat larger size and body mass of males (15-20 kg) compared to females (10-13 kg). Numerous subspecies of dhole have been proposed and in turn questioned, forming two groups, one to the north and one to the south of its distribution area, which appear to follow Bergmann’s rule1.

The dhole is clearly adapted to a hypercarnivorous diet, which, from the osteological point of view, is mainly reflected in the cranial and dental morphology2. The skull is wide, with a convex profile and a reduced anterior region. The mandible is short and has trenchant, pointed premolars. The genus (Cuon Hodgson, 1838) shows 40 teeth, featuring the absence of m3, reduction and simplification of M1 and m23, and the presence of a single cusp (hypoconid) on the talonid of m14.

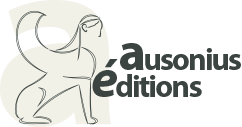

Little is known about the characteristics of these canids in Europe, which were distributed throughout much of the continent during various phases of the Pleistocene5. In the case of the Iberian Peninsula, the presence of this canid in the fossil record was reported for the first time at the beginning of the last century6. Within this geographical setting, different studies identify dhole populations from the Middle Pleistocene7, throughout the Late Pleistocene8 (with the largest number of references) and possibly remaining in some areas of the Mediterranean until the early Holocene9.

The appearance of dhole remains at archaeological and palaeontological sites is the result of different processes of interaction with human groups or other carnivores due to the use of caves and access to prey10. The few dhole remains identified in the Iberian and European archaeo-palaeontological record, primarily teeth and cranial elements, suggest that fossil populations would have been more robust than present-day populations11. Morphometric studies are currently being carried out on several unpublished dhole assemblages from Middle and Late Pleistocene sites in the Mediterranean and Cantabrian regions of the Iberian Peninsula. These new assemblages will provide a better taxonomic characterisation of Pleistocene dhole populations and will increase the fossil record of this canid and its distribution area12.

With regard to the phylogeny of the genus, Adam13 considers that the different species of dhole have a common origin and proposes the existence of three subspecies of Cuon alpinus: C. a. priscus, C. a. fossilis and C. a. europaeus. Bonifay14, on the other hand, believes that the different species are separate and correspond to three waves of migration from Asia to Europe. Brugal & Boudadi-Maligne15 presented a proposal regarding size evolution among European dhole populations throughout the Pleistocene based on the dimensions of m1 and m2, observing size differences between those of the Middle Pleistocene (with larger teeth) and those of the Late Pleistocene (with smaller teeth). In this regard, during the Middle Pleistocene there would have been two subspecies of Cuon priscus Thenius, 1954, the first with larger teeth at older sites and the second with narrower teeth at more modern sites. Cuon alpinus europaeus Bourguignat, 1868, would have been present during the Late Pleistocene, with smaller teeth and similar proportions to those of present-day dholes. Thus, the results of the study by Brugal & Boudadi-Maligne show at least three stages regarding the tooth morphometry of European Pleistocene dholes. They propose two dispersion events of this genus into Europe, the first during the Middle Pleistocene by C. priscus, and another of throughout the Late Pleistocene by C. alpinus, coinciding with a gradual reduction in the tooth dimensions of these two chronospecies.

The aim of this work is to study the diachronic evolution of tooth size in Cuon fossil populations in the Iberian Peninsula and thereby verify the proposal put forward by Brugal & Boudadi-Maligne. Measurements of the postcranial skeleton of Iberian fossil dholes are also included to determine whether this process is related to changes in general skeletal dimensions. Based on these data we consider two questions: did Middle Pleistocene dholes, with larger teeth than those of the Late Pleistocene, also have a larger body than those of the Late Pleistocene and is there, consequently, a direct relationship between the decrease in tooth size and body size? Or is the process of tooth size evolution related to specific adaptations in feeding behaviours? In this regard, in addition to changes in the dimensions of the teeth, it is also necessary to consider their morphology and verify whether they display features related to the development of hypercarnivorous feeding behaviours16: presence of an anterior denticle (paraconid) on p4, reduction of the talonid of m1 and therefore of the relationship between the cutting part (trigonid) and the crushing part (talonid), and simplification of m2. Finally, we propose a taxonomic classification of Pleistocene dhole populations in the Iberian Peninsula based on the dental morphometric features of three mandibles from the Mediterranean and Cantabrian regions.

Materials and methods

In some cases the biometric data regarding the teeth and postcranial remains of Iberian fossil dholes are taken from published works17 (see the measurements), but others are as yet unpublished and correspond to the database of the dhole fossil record in the Iberian Peninsula (Fig. 1) created by our team in recent years18. The measurements of fossil remains are compared to those of different specimens of extant dholes, 12 skeletons belonging to two Asiatic geographical varieties: one (Cuon alpinus lepturus Heude, 1892) from the south of the Yangtze River in China (six males, 3267, 6412, 6764, 6765, 6784 and 7106) and the other (Cuon alpinus javanicus-sumatrensis Desmarest, 1820) from the islands of Java and Sumatra in Indonesia (two males, 1963-330 and 1927-1251, one female, 1927-1252, and three individuals of undetermined sex, 1930-228, 2007-473 and A1G38)19. The individuals from China come from the collection of the Museo Anatómico de la Universidad de Valladolid (Anatomy Museum of the University of Valladolid) (Spain) and those of Indonesia come from the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (National Museum of Natural History) in Paris (France). The dimensions of 15 extant wolf skeletons (Canis lupus signatus Cabrera, 1907) from different locations in the north of the Iberian Peninsula have also been included for comparative purposes. On the one hand, 12 individuals (the mean is provided in figures 2, 4 and 5) from the collections of the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (National Museum of Natural Sciences) in Madrid (Spain): six males (16166, 16241, 16225, 16239, 16242 and 16153), three females (16167, 16162 and 21561) and three individuals of undetermined sex (16235, 16218 and 16219). On the other hand, three individuals from the Estación Biológica de Doñana (Doñana Biological Station) in Seville (Spain): two males (15903 and 15891) and one female (23272). The measurements of wolf fossil remains from Pleistocene sites in the Iberian Peninsula have also been considered, from both the Cantabrian20 and Mediterranean21 regions. With the aim of increasing the sample size, metric data corresponding to Pleistocene wolves from France (the mean is provided in figures 2, 4 and 5) have also been used22.

The biometric information for these dhole and wolf populations has been used to create different bivariate scatter plots and boxplots (mean, minimum, maximum and standard deviation are provided) to illustrate the conclusions of the comparative study between populations (fossil and modern) and genera, in terms of both the dental (p4, m1, P4 and M1) and postcranial (radius) remains23. To obtain it, free software Past3© has been used.

The degree of hypercarnivory in Cuon has been assessed based on the presence of certain features in the lower teeth: the presence of the paraconid on p4, reduction of the metaconid of m1, reduction of the talonid of m1 (relationship between the length of the talonid and trigonid; width of the talonid) and simplification of m224.

Morphometry of the genus Cuon in the Iberian Peninsula

Tooth dimensions (p4, m1, P4 and M1)

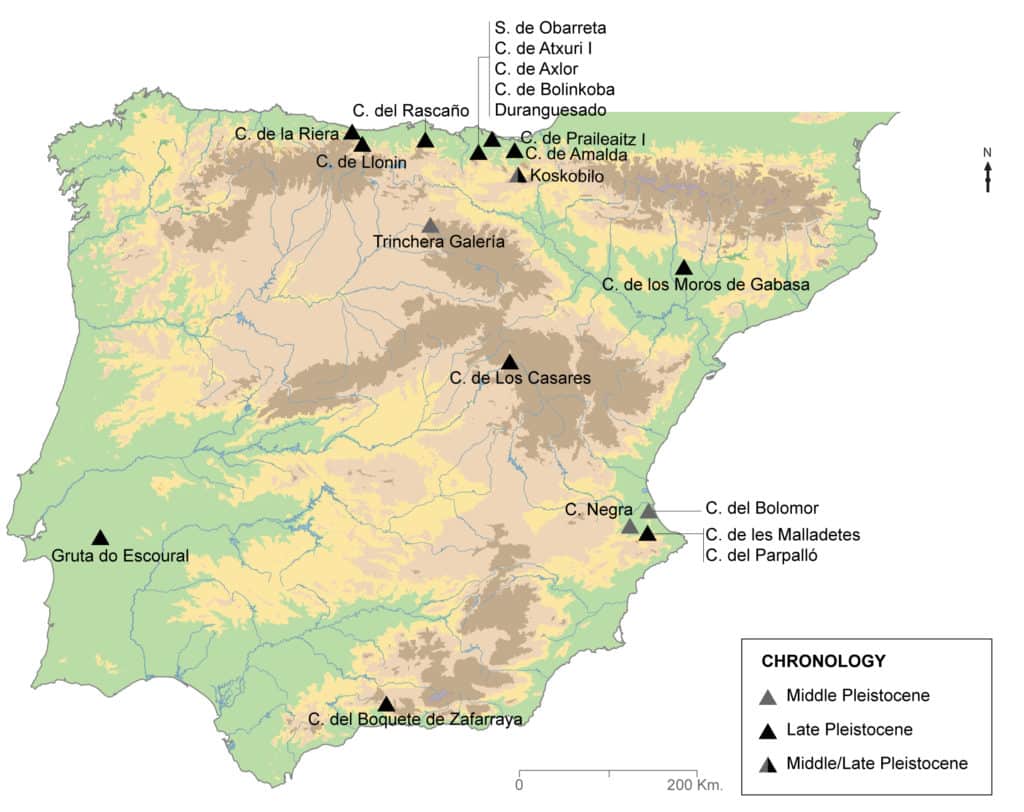

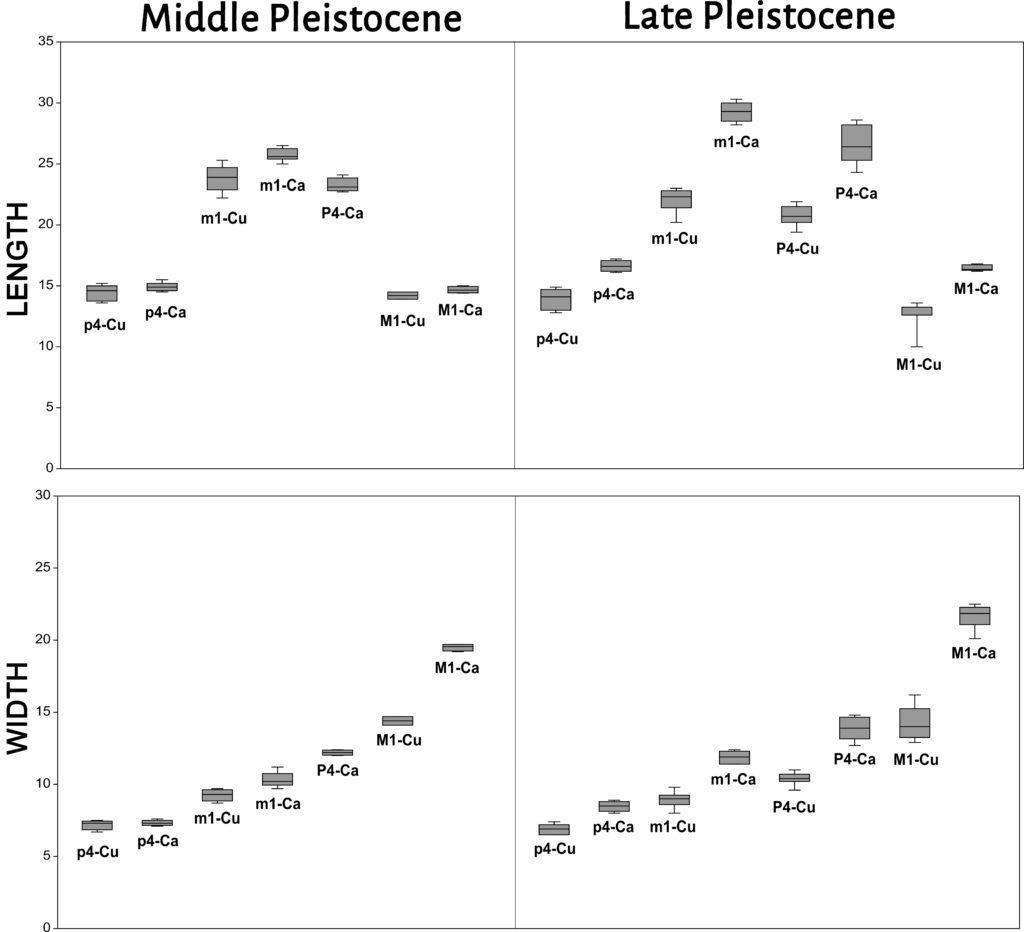

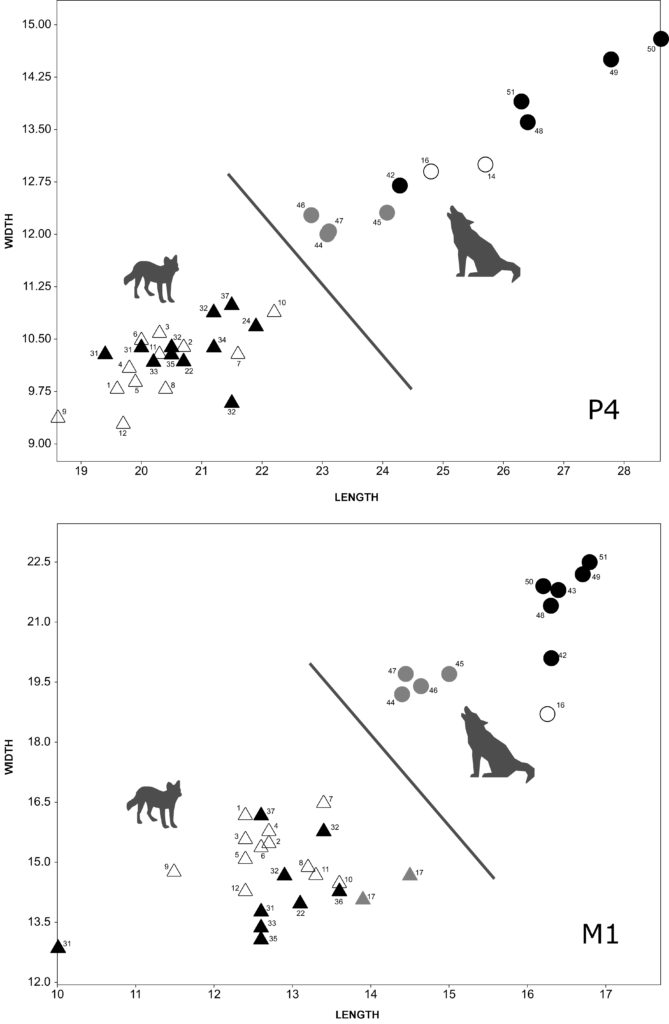

We compared the length and the width of p4 of Iberian fossil dholes from the Middle Pleistocene (Trinchera Galería, Cova Negra and Bolomor, n = 5) and the Late Pleistocene (Llonin, Los Casares, Gabasa, Rascaño, Duranguesado, Atxuri I, Praileaitz I, Koskobilo, Escoural and Zafarraya, n = 11) with those of modern specimens from China (n = 6) and Indonesia (n = 5) and with those of modern wolves (n = 15) and Iberian fossil wolves from the Middle Pleistocene (Bassa de Sant Llorenç, n = 1)25, and fossil wolves from France26 from the Middle Pleistocene (Lunel-Viel 1, n = 21; Igue des Rameaux, n = 64; Aven 1 de La Fage, n = 8; Coudoulous I, n = 6) and the Late Pleistocene (Aven de l’Arquet, n = 18; Jaurens, n = 15; Maldidier, n = 5; Igue du Gral, n = 12). In general, the p4 of modern and fossil dholes have smaller dimensions than those of modern and fossil wolves (Fig. 2). In any case, an overlap is observed between the p4 of small wolves from the Middle Pleistocene and those of some larger Iberian fossil dholes from the same chronology (Cova Negra, Trinchera Galería) (Fig. 3). Fossil dholes have larger p4s than modern dholes, with an overlap in some cases between those of the Middle and Late Pleistocene. If we compare the dimensions of the p4 of modern dholes from Indonesia, the male (1927-1251) has a larger length and width than the female (1927-1252); the dimensions of the p4 of the male dholes from China are larger than those of the two individuals from Indonesia. Late Pleistocene wolf p4s are larger than those of the Middle Pleistocene.

The length and width of the m1 of Iberian fossil dholes from the Middle Pleistocene (Trinchera Galería, Cova Negra, Bolomor and Koskobilo, n = 6) and the Late Pleistocene (Llonin, Parpalló, Los Casares, Gabasa, Obarreta, Rascaño, Duranguesado, Axlor, Amalda, Bolinkoba and Zafarraya, n = 13) have been compared with those of present-day specimens from China (n = 6) and Indonesia (n = 5) and with those of modern wolves (n = 15) and Iberian fossil wolves from the Middle Pleistocene (Bassa de Sant Llorenç and Cova del Corb, n = 5)27 and the Late Pleistocene (Urtiaga and Erralla, n = 3)28, and fossil wolves from France29 from both the Middle (Lunel-Viel 1, n = 24; Igue des Rameaux, n = 82; Aven 1 de La Fage, n = 7; Coudoulous I, n = 9-8) and Late Pleistocene (Aven de l’Arquet, n = 28; Jaurens, n = 19; Maldidier, n = 3; Igue du Gral, n = 10). In general, the m1 of extant and fossil dholes have smaller dimensions than those of both modern and fossil wolves (Fig. 2). However, a certain degree of overlap has been observed between the m1 of small wolves from the Middle Pleistocene and those of large Iberian fossil dholes from that same chronology, affecting the length more than the width (Fig. 3). If we compare the length of the m1 of fossil dholes and present-day specimens, those of the Late Pleistocene have values that are similar in some case to the modern ones, while in general the Iberian dholes from the Middle Pleistocene (Trinchera Galería, Bolomor, Cova Negra and Koskobilo) are larger than those of the Late Pleistocene and modern dholes. In the case of the width of m1, the differences between the dholes from the Middle and Late Pleistocene are not as clear as in the case of the length. If we compare the dimensions of the m1 of modern dholes, it can be observed that the males from China and Indonesia have longer, wider teeth than the single female from Indonesia. The m1 of wolves from the Late Pleistocene are larger than those of the Middle Pleistocene.

The length and width of the P4 of Iberian fossils from the Late Pleistocene (Llonin, Parpalló, Obarreta, La Riera, Axlor, Gabasa, Zafarraya and Amalda, n = 11) have been compared with those of present-day specimens from China (n = 6) and Indonesia (n = 6) and with those of modern wolves (n = 15) and Iberian fossil wolves from the Late Pleistocene (Lezetxiki, n = 1)30, and fossil wolves from France31 from the Middle Pleistocene (Lunel-Viel 1, n = 23; Igue des Rameaux, n = 59; Aven 1 de La Fage, n = 3; Coudoulous I, n = 6-7) and the Late Pleistocene (Aven de l’Arquet, n = 26; Jaurens, n = 7; Maldidier, n = 3; Igue du Gral, n = 10). In this case, there are clear differences in the dimensions of the P4s between dholes and wolves, although this may be due to the lack of both measurements and references of Middle Pleistocene dholes (Fig. 4). The comparison between fossil and present-day dholes does not offer such clear results as those observed for m1. In the case of the P4 of Iberian fossil dholes, due to the lack of measurements for dholes from the Middle Pleistocene, it is not possible to confirm the trend observed for m1 in terms of the progressive decrease in length. With regard to modern dhole populations, such as those of Indonesia, the P4s of the males show larger length and width than females. There are no clear differences in the size of P4 between the dholes of China and Indonesia. The P4 from the Late Pleistocene wolves are larger than those of the Middle Pleistocene.

With regard to M1, the length and width of Iberian fossil dholes from the Middle Pleistocene (Trinchera Galería, n = 2) and the Late Pleistocene (Llonin, Parpalló, Obarreta, La Riera, Bolinkoba, Zafarraya and Amalda, n = 9) have been compared with those of present-day specimens from China (n = 6) and Indonesia (n = 6) and with those of modern wolves (n = 14) and Iberian fossil wolves from the Late Pleistocene (Lezetxiki and Marizulo, n = 2)32, and fossil wolves from France33 from the Middle Pleistocene (Lunel-Viel 1, n = 20; Igue des Rameaux, n = 51; Aven 1 de La Fage, n = 3; Coudoulous I, n = 7-6) and the Late Pleistocene (Aven de l’Arquet, n = 19; Jaurens, n = 6; Maldidier, n = 2; Igue du Gral, n = 12). In general, the measurements of dholes and wolves are clearly differentiated, although a certain degree of overlap is observed during the Middle Pleistocene between the length of fossil dholes (Trinchera Galería) and that of fossil wolves (Fig. 3, 4). The comparison between fossil and modern dholes also shows an overlap in some cases. If we compare the dimensions of the M1 of fossil dholes, it can be seen that the length of those of the Middle Pleistocene is larger than that of those of the Late Pleistocene; however, there is some overlap in relation to the width. With regard to wolves, those of the Late Pleistocene from the Iberian Peninsula and France show similar dimensions and are larger than those of Middle Pleistocene wolves from France.

Postcranial dimensions

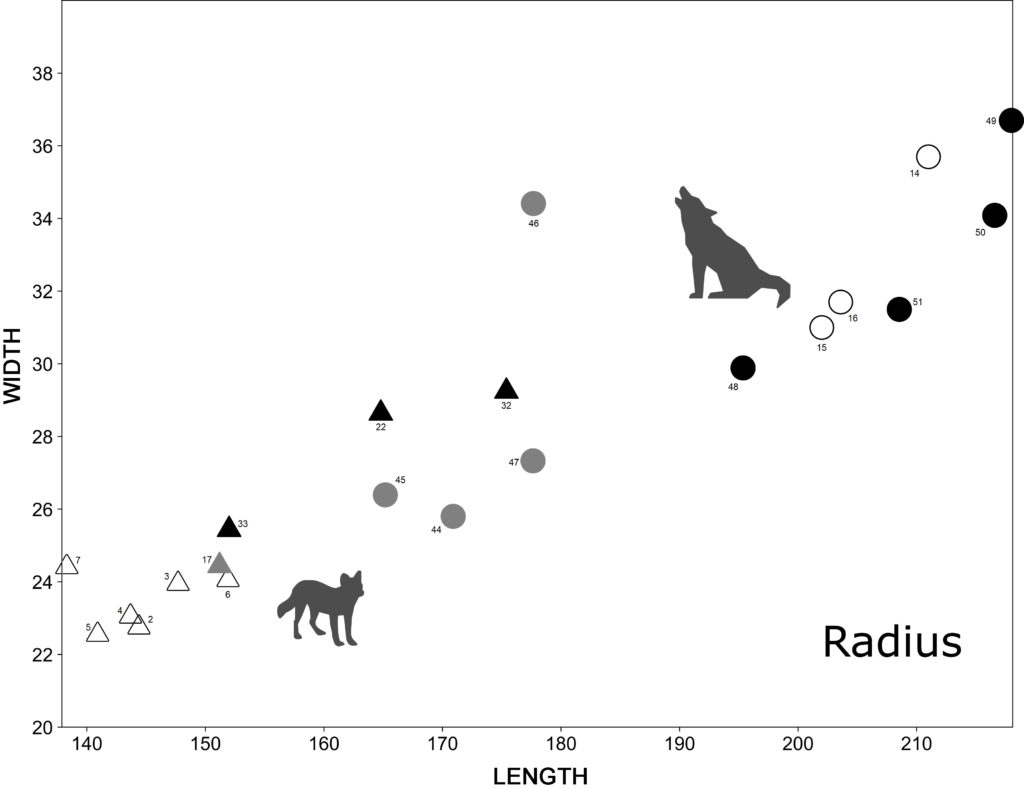

There is little information about the size of the postcranial skeleton of fossil dholes from the Iberian Peninsula. The most abundant postcranial remain is the radius which provides the greatest number of comparative measurements between genera and sites, for which the greatest length and the transverse distal width of Iberian fossil dholes from the Middle Pleistocene (Trinchera Galería, n = 1) and the Late Pleistocene (Obarreta, Llonin and Parpalló, n = 3) have been compared with those of present-day specimens from China (n = 5) and Indonesia (n = 1) and with modern Iberian wolves (n = 11) and fossil wolves from both Middle (Lunel-Viel 1, n = 1; Igue des Rameaux, n = 7-8; Aven 1 de La Fage, n = 1-5; Coudoulous I, n = 1-4) and Late Pleistocene (Aven de l’Arquet, n = 4-10; Jaurens, n = 2; Maldidier, n = 3; Igue du Gral, n = 2-3) sites. The radii of fossil dholes from the Late Pleistocene show larger dimensions than those of modern dholes and of the Middle Pleistocene specimen from Trinchera Galería (Fig. 5). The only Middle Pleistocene specimen has a greater distal breadth than modern ones, and the length is also greater than most of the present-day ones, except in one case. Some overlap is observed between the dimensions of the radii of Iberian fossil dholes from the Late Pleistocene and those of fossil wolves from the Middle Pleistocene (Lunel-Viel 1, Igue des Rameaux and Coudoulous I). The fossil wolves from the Late Pleistocene have a larger radius. With regard to modern dholes, the males from China have a longer radius than the one from Indonesia, although the distal breadth is similar.

The sample is very small for the other postcranial elements of fossil dholes from the Iberian Peninsula. There are three complete femora from the Late Pleistocene: at Obarreta34, Parpalló35 and Llonin36. The dimensions (GL and Bd t) of the latter two are greater than those of modern dholes, although the femur from Obarreta has a similar size or is even smaller than some modern dholes, which could be related to the likely female status of this individual based on its general small skeletal size and the absence of baculum37. With regard to the tibia, there are only two complete remains from the Late Pleistocene: one from the skeleton from Obarreta and the other from Malladetes38. The dimensions of the tibia from Malladetes are larger than those of modern dholes, while the ones from Obarreta are similar to those of present-day Asian dholes. Regarding the French fossil wolves, the radii, femora and tibiae of Middle Pleistocene wolves have small dimensions, whereas those of Late Pleistocene wolves generally have larger long bones.

Dental morphology and hypercarnivorism

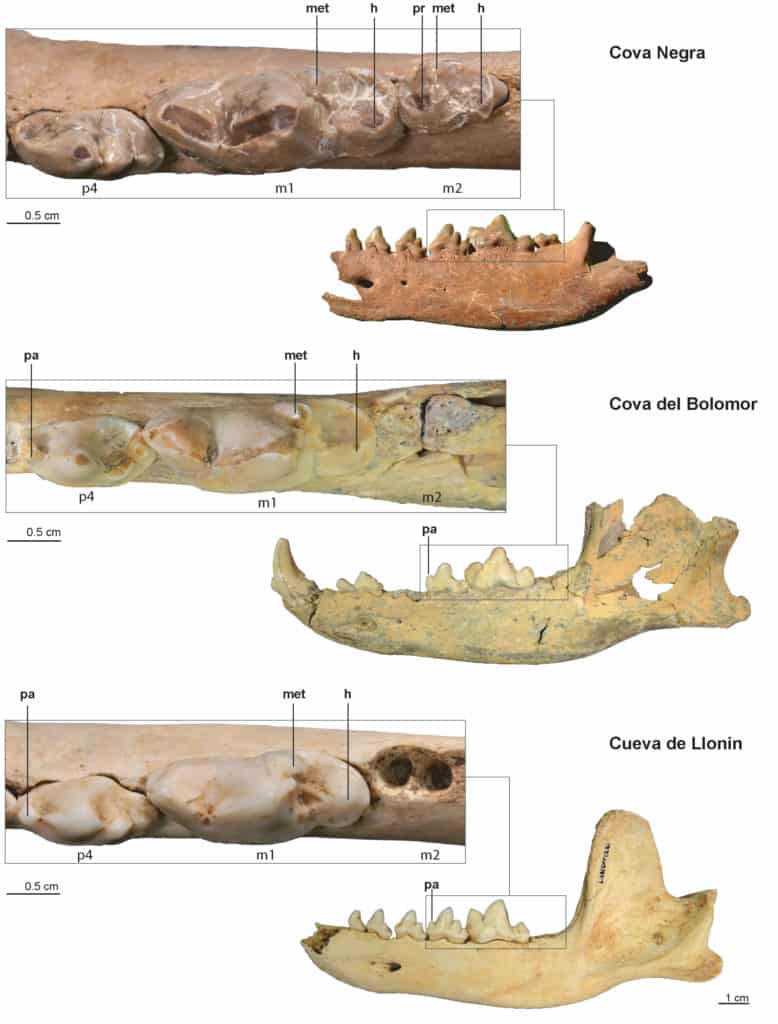

A comparison has been made of the tooth morphology of three left hemimandibles of fossil dholes from the Iberian Peninsula, which show well-preserved teeth and have also been chronostratigraphically assigned (Fig. 6). Two of them come from two Middle Pleistocene sites in the Mediterranean region: Cova Negra, from MIS 7-839 and Cova del Bolomor, from MIS 640; the third comes from Cueva de Llonin, a Late Pleistocene site (MIS 3) in the Cantabrian region41.

• Cova Negra, Xàtiva, Valencia (30246, CN 9830, entrance slope, layer 7). This hemimandible (Fig. 6) was previously classified by us as Cuon cf. alpinus42, as it presents various archaic features in terms of the dentition and dimensions (of the teeth) that are more in line with other older fossils of the genus, bearing in mind its stratigraphic position within the Late Pleistocene (MIS 5d-b). Therefore, due to the aforementioned characteristics and the new datings of the archaeological deposit at the site that place the fossil at an earlier stage, during the Middle Pleistocene, MIS 7-843, we have reclassified this specimen. In addition to the significant size of the teeth, it also has an alveolar length (p1-m2) of 77.1 mm. With regard to the main characteristics of the teeth (Fig. 6), the p4 does not present an anterior cusp and the m1 still shows a well-developed metaconid and a wide talonid (width of the talonid: 8.6 mm) with a single cusp, a hypoconid, in the central position, although a small cingulid is still observed around the lingual surface; the relationship between the length of the talonid and the trigonid of the m1 gives a ratio of 37. The m2 is well developed and has a rectangular profile, with a complex morphology consisting of three cusps, two anterior protoconid and metaconid cusps and a posterior hypoconid, a wide talonid and an alveolus with two roots. The relationship between the length of m1 and m2 gives a ratio of 27.2.

• Cova del Bolomor, Tavernes de la Valldigna, Valencia (24231, CB 2007, N10 EX no.1). The full description and measurements of this hemimandible (Fig. 6) and the dentition will be presented in a separate work44. The p1-m2 alveolar length of the piece is 75.3 mm. We can advance here that the p4 presents an anterior cusp or paraconid, the m1 has a less developed metaconid, but the talonid is still wide (width of the talonid: 8.1 mm) with one cusp, a hypoconid, in the central position, and a cingulid on the lingual edge that is not very pronounced. The relationship between the talonid and the trigonid of the m1 gives a ratio of 28. The m2 is missing and its alveolar process shows two alveoli for two roots, currently filled with a breccia-like material.

• Cueva del Llonin, Peñamellera Alta, Asturias (LLO 1988, VIII, CP, BCD/11-12, 281). The full description and measurements of this hemimandible (Fig. 6) and the dentition will be presented in a separate work45. The p1-m2 alveolar length of the remains is 69.4 mm. We can advance that the p4 presents an anterior cusp or paraconid, and the m1 has an underdeveloped metaconid and a narrower talonid (width of the talonid: 7.4 mm) with one cusp in the central position (hypoconid), and a barely discernible cingulid on the lingual edge. The relationship between the talonid and the trigonid of the m1 gives a ratio of 30. The m2 is missing and its alveolar process shows two alveoli for two roots.

With regard to the comparative study of the three hemimandibles of fossil dholes, in the case of Cova Negra the presence of archaic features in its teeth and their dimensions, in addition to the chronostratigraphic situation of the remains, have allowed us to reclassify this specimen as Cuon cf. priscus, coinciding with other Middle Pleistocene fossils in Europe46. The remains from Cova Negra are the only one of the three hemimandibles for which m2 is preserved. This tooth has a similar morphology and arrangement of the cusps to those of the Middle Pleistocene specimens from Lunel-Viel47, which are attributed to Cuon priscus. However, the m2 fossil record from the Iberian Peninsula is rather scarce and has not yielded any conclusive data, as the three specimens from Trinchera Galería48 show more evolved features than the one from Cova Negra. The ratio between the length of the m1 and m2 from Cova Negra (27.2) is similar to the values for other individuals from Middle Pleistocene contexts, which are below 30 (Lunel-Viel, Trinchera Galería), and it is far from those of the Late Pleistocene, such as 32.8 for Obarreta49 and 36.8/37.5 for Praileaitz I50. Both the morphology and the considerable development of the m2 from Cova Negra are typical of dholes from the Middle Pleistocene in Europe. In addition to this, we have a lack of paraconid on the p4, the development of the metaconid and considerable width of the talonid on the m1 with a small cingulid still present.

The hemimandible from Llonin is a clear example of dholes from the Late Pleistocene in Europe. Its teeth show smaller dimensions and similar proportions to those of modern dholes and have highly hypercarnivorous features (presence of a paraconid on the p4, the m1 with a diminishing metaconid and a narrow talonid), all of which could be assigned to Cuon alpinus europaeus.

Somewhere between the two previous specimens is the hemimandible from Bolomor, which corresponds to a more advanced phase of the Middle Pleistocene than the one from Cova Negra. The remains from Bolomor still show certain archaic features with regard to the width of the talonid, although the metaconid is less developed than in the case of Cova Negra; however, they also present other features that are more common among dholes from the Late Pleistocene (anterior cusp on the p4 and smaller dimensions).

Discussion

With regard to the tooth dimensions of Iberian fossil dholes, the M1 and m1 of specimens from the Middle Pleistocene are longer (mesio-distally) than those of the Late Pleistocene. In the studied sample we have noted a process of reduction of the size of these two teeth from the Middle to the Late Pleistocene. A greater overlap of measurements is observed for p4, in terms of both length and width, whereas no comparison can be made in the case of P4 due to the absence of remains from the Middle Pleistocene. There is greater variation in the width of m1, p4 and M1 between the individuals from these two periods. In fossil wolves we see the opposite phenomenon to that observed in fossil dholes, as the tooth dimensions (both length and width) actually increase from the Middle to the Upper Pleistocene51.

As a consequence of these dynamics affecting the dimensions of the teeth of both genera, dholes with longer teeth and wolves with shorter teeth, such as Canis lupus lunellensis, would have been present in the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Pleistocene. In some cases, this results in overlapping measurements (length of m1, p4 and M1) (Fig. 3). Dholes with shorter teeth and wolves with longer teeth would have coincided during the Late Pleistocene, so there is no possibility of any overlap in the measurements of these genera; in this latter case the dimensions are a useful criterion for differentiating between the two genera.

Despite the small size of the sample, the comparison of tooth dimensions in present-day dholes from Indonesia shows that the males have longer, wider teeth than the females, consistent with the observed general body size sexual dimorphism. Present-day male dholes from China and Indonesia have similar-sized teeth, but show differences in the length of the radius. This variation in postcranial size is also observed in fossil dholes and may be related to sexual dimorphism and the geographical origin of populations. Unfortunately, the lack of postcranial dhole remains from sexed individuals means that we cannot compare tooth dynamics with a change in the size of postcranial bones. Likewise, due to the lack of dhole tooth fossils from sexed specimens (apart from the possible female from Obarreta), we are unable to confirm the trend observed in present-day populations, with males having larger teeth than females. However, in the case of Trinchera Galería the size differences of the p4 and m1 in the samples could be related to sexual dimorphism, as the smaller individual (TG1) is possibly a female.

If we compare the morphology of the m1 from the Iberian fossil record with those of the hemimandibles analysed, those of the Late Pleistocene (Obarreta, Rascaño, Zafarraya, Gabasa and Duranguesado) show a talonid with a single cusp in the central position and a very subtle or non-existent cingulid, as is the case at Llonin; one exception is the m1 from Los Casares, which presents more archaic features52. The m1s from Trinchera Galería show a more pronounced cingulid, like that observed at Cova Negra. It remains to be confirmed whether the reduction of the cingulid on the m1 observed in the Late Pleistocene specimens is related to an increase in hypercarnivory or is simply a consequence of the reduction in general tooth size. The degree of development of the metaconid seems to be a more variable criterion among the Iberian fossil dholes, as it is small in some cases (e.g. Trinchera Galería, Gabasa, Rascaño and Llonin) but quite pronounced in others (e.g. Los Casares and Obarreta).

The presence of a paraconid on p4 is a feature that has traditionally been associated with Late Pleistocene dholes53. In this regard, all the p4 from Late Pleistocene sites in the Iberian Peninsula (Llonin, Escoural, Rascaño, Los Casares, Zafarraya, Gabasa, Duranguesado, Atxuri I, Praileaitz I and Axlor) show this feature. In the case of the p4 from Middle Pleistocene sites, some have an anterior denticle, like the three specimens from Trinchera Galería (classified as Cuon alpinus54) and the one from Bolomor that we present here, while the specimen from Cova Negra does not.

The anterior denticle on p4, which always appears in Late Pleistocene European dholes, only does so frequentially in those of the Middle Pleistocene (and in modern dholes). This could be the result of selection within a general tendency towards hypercarnivory. Alternatively, it cannot be ruled out that this feature may have become fixed randomly (founder or bottleneck effects). In this respect, and in order to understand the continuity or discontinuity of dhole populations in Europe, to understand their relationship with modern dhole populations and to test the hypotheses posed on the basis of the fossil remains, it would be recommendable to carry out ancient DNA studies on fossil dholes from the Iberian Peninsula and other parts of Europe. Similar studies have been carried out for other extirpated carnivores in Europe, such as Eurasian cave lions (Panthera spelaea55) or spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta56), with interesting results. These studies have shed light on the relationship between fossil populations in Europe and present-day populations, and, in combination with the fossil record, have enabled hypotheses to be put forward on how these species would have populated Europe.

Until the taxonomy of the remains from Bolomor is established for certain, we can argue that it could be a transitional form between the dholes with larger teeth from the Middle Pleistocene, such as the one from Cova Negra (C. cf. priscus), and the more slender dholes of the Late Pleistocene, such as the one from Llonin (C. alpinus europaeus). Thus, the specimen from Bolomor poses interesting questions about the phylogeny of the genus in the Iberian Peninsula: is it a more derived Cuon priscus? Is it an individual that may reveal an early appearance of Cuon alpinus in the Middle Pleistocene? If the genus Cuon entered the Iberian Peninsula in several different waves, could these different groups of dholes have interbred? Or is the derived morphology observed in Late Pleistocene dholes the result of an evolution that took place over time in Europe, with intermediate (or polymorphic) forms during the Middle Pleistocene, which became established subsequently?

With regard to the alveolar length of the three studied specimens, a reduction is observed from the older to the more recent fossils. This is related to the dimensions of the teeth and the existence of diastemata between them. In this regard, the Middle Pleistocene mandibles from the Iberian Peninsula have the highest values, such as those of Cova Negra (77.1), Bolomor (75.3), TG1 (72.8) and TG3 (73.9), while those of the Late Pleistocene: Llonin (69.4), Obarreta (67) and Duranguesado (67.6) show lower values; Parpalló is somewhere in between, with a value of 71.9.

The aforementioned observations regarding tooth dimensions between genera and samples are true in the case of the three analysed hemimandibles. The width of the talonid of m1 decreases from the specimen from Cova Negra to the one from Bolomor and lastly to the one from Llonin, which seems to confirm a progressive reduction in the width of the crushing area of the lower carnassial tooth, although this could also be a direct consequence of the general reduction in tooth size. In general, a decrease in the length of the m1 is also observed in the three hemimandibles. With some reservations, we consider that this process of reduction in tooth dimensions may be related to a greater degree of hypercarnivory in Late Pleistocene dholes. The few metric data for postcranial elements of Cuon seem to confirm this tendency.

Future studies should also consider the distribution/overlap of ecological niches between Canis and Cuon, and whether there were changes in these niches that were occupied throughout the Pleistocene57; changes in the overall size of the body and teeth observed in wolves and dholes are mechanisms for differentiating the niche resulting in less competition between these species.

Conclusions

The Pleistocene fossil dholes from the Iberian Peninsula have larger teeth and longer bones than extant dhole populations. Although there are some data on differences in tooth size depending on the sex of modern dholes, the degree of sexual dimorphism of Iberian fossil populations, in terms of either teeth or postcranial elements, is yet unknown due to the general scarcity of their fossils and the lack of enough individuals from the same chronology.

Based on the metric study of dhole tooth fossils, we have observed differences in the length of m1 and M1, which is larger in Middle Pleistocene populations and smaller in those of the Late Pleistocene. It has not been possible to corroborate this with the postcranial skeleton, due to the small sample size, which does not allow to properly address this question.

Based on the comparative study of three dhole hemimandibles from the Iberian Peninsula, it is possible to observe the existence of three stages in the dental morphometry of Pleistocene dholes from the Iberian Peninsula, partially confirming the proposal put forward by Brugal and Boudadi-Maligne (2011): Cuon cf. priscus during older phases (MIS 7-8) of the Middle Pleistocene (Cova Negra), Cuon alpinus europaeus during the Late Pleistocene (Llonin), and in between these the specimen from Bolomor, with a mixture of archaic and derived features.

The fact that Late Pleistocene dholes have smaller teeth than those of the Middle Pleistocene may be related primarily to specific adaptations in feeding behaviours, regardless of the size of the individuals. However, the fossil dhole references available are currently insufficient and the geographic-chronological study framework is very wide. Therefore, in order to confirm our proposal, it is necessary to increase the corpus of data.

Acknowledgements

We would like to dedicate this contribution to the late Manuel Pérez Ripoll, in memoriam. We would like to thank: J. B. Mallye and M. Boudadi-Maligne, the organisers of the talk “Relations Hommes/Canidés, de la Préhistoire aux périodes modernes”, for their invitation to participate in it and for the chance to publish in this monograph. The authors thank the Estación Biológica de Doñana (Sevilla) and the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (Madrid) for the loan and consultation of wolf skeletons. Also, we thank the Museo Anatómico de la Universidad de Valladolid and the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (Paris) for the loan and acces to the dhole collections for their study.

This work has been funded by the following projects: MINECO2015-HAR2014-59183-P “Paleoambiente, Economía y Sociedad durante el MIS 3 en el Occidente Cantábrico” (Palaeoenvironment, Economy and Society during MIS 3 in the Western Cantabrian region); PROMETEOII/2013/016 and PROMETEO/2017/060). This work was also supported by the Research Groups IT1044-16 (Eusko Jaurlaritza-Gobierno Vasco), PPG17/05 (Universidad del País Vasco-Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea) and by the Spanish FEDER/Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación-Agencia Estatal de Investigación (project PGC2018-093925-B-C33). AGO was supported by the Ramón y Cajal fellowship (RYC-2017-22558).

Bibliography •••

- Adam, K.D. (1959): “Mittelpleistozäne Caniden aud dem Heppenloch bei Gutenberg (Württemberg)”, Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, 27, 1-46.

- Altuna, J. (1972): “Fauna de mamíferos de los yacimientos prehistóricos de Guipúzcoa”, Munibe, 24, 1-464.

- Altuna, J. (1973): “Fauna de mamíferos del yacimiento prehistórico de Los Casares (Guadalajara)”, in: Barandiarán, I., ed., La Cueva de Los Casares, en Riba de Saelices, Guadalajara, 97-116.

- Altuna, J. (1981): “Restos óseos del yacimiento prehistórico de Rascaño (Santander)”, in: González Echegaray, J. & Barandiarán, I., ed., El paleolitico superior de la cueva del Rascaño (Santander), 221-269. http://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/dam/jcr:bbe79d13-7524-4bcb-a5fc-f882084b218a/pdf03-echegaray-barandiaran-1981-rascano.pdf

- Altuna, J. (1983): “Hallazgo de un cuón (Cuon alpinus Pallas) en la sima de Obarreta, Gorbea (Vizcaya)”, Kobie, 13, 141-158.

- Altuna, J. (1986): “The mammalian faunas from the prehistoric site of La Riera”, in: Straus, L.G. & Clark, G.A., ed., La Riera Cave, ASU Anthropological Research Papers 36, 237-274.Altuna, J. (1990): “Caza y alimentación procedente de macromamíferos durante el Paleolítico de Amalda”, in: Altuna, J., Baldeón, A. & Mariezkurrena, K., dir., La Cueva de Amalda (Zestoa, País Vasco): Ocupaciones paleolíticas y postpaleolíticas, Colección Barandiaran 4, 149-192. https://www.bizkaia.eus/fitxategiak/04/ondarea/Kobie/PDF/7/Kobie_BAI_3_web-8.pdf?hash=9e283971a049fc1126ab453138dbc843

- Arceredillo, D., Gómez-Olivencia, A. and SanPedro-Calleja, Z. (2013): “La fauna de macromamíferos de los niveles pleistocenos de la Cueva de Arlanpe (Lemoa, Bizkaia)”, in: Excavaciones arqueologicas en Bizkaia, 3, 123-160.

- Barnett, R., Shapiro, B., Barnes, I. A. N., Ho, S. Y. W., Burger, J., Yamaguchi, N., Higham, T. F. G., Wheeler, H. T., Rosendahl, W., Sher, A. V., Sotnikova, M., Kuznetsova, T., Baryshnikov, G. F., Martin, L. D., Harington, C. R., Burns, J.A. and Cooper, A. (2009): “Phylogeography of lions (Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity”, Molecular Ecology, 18(8), 1668-1677.

- Barroso, C., Riquelme, J.A., Moigne, A.M. and Banes, L. (2006): “Les faunes de grands mammifères du Pléistocène supérieur de la Grotte du Boquete de Zafarraya. Étude Paléontologique, Paléoécologique et Archéozoologique”, in: Barroso, C. & de Lumley, H., ed., La grotte du Boquete de Zafarraya, Málaga, Andalousie, Sevilla, 675-891.

- Blasco, M.F., ed. (1995): Hombres, fieras y presas. Estudio arqueozoológico y tafonómico del yacimiento del Paleolítico Medio de la Cueva de Gabasa 1 (Huesca), Dpto. Ciencias de la Antigüedad (Área de Prehistoria). Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza.

- Bonifay, M. F., ed. (1971): Carnivores quaternaires du Sud-Est de la France, Paris. Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle.

- Boudadi-Maligne, M. (2010): Les Canis pléistocènes du sud de la France: approche biosystématique, évolutive et biochronologique, thèse de doctorat, université Bordeaux I.

- Bourguignat, J.R., ed. (1875): Recherches sur les ossements de Canidae constatés en France à l’état fossile pendant la période quaternaire, Paris.

- Brugal, J.P. (2004): “First Middle Pleistocene faunas with primates (Homo, Macaca) from Estremadura (Portugal)”, in: 18th International Senckenberg Conference, VI International Paleontological Colloquium in Weimar, “Late Neogene and Quaternary Biodiversity an Evolution: Regional Developments and Interregional Correlations”, 25-30 April 04, Weimar, Terra Nostra 2, 82-83.

- Brugal, J.P. and Boudadi-Maligne, M. (2011): “Quaternary small to large canids in Europe: Taxonomic status and biochronological contribution”, Quaternary International, 243, 171-182.

- Brugal, J.P. and Fosse, P. (2004): “Carnivores et hommes au Quaternaire en Europe de l’Ouest”, Revue de Paléobiologie, 23 (2), 575-595.

- Cardoso, J.L., ed. (1993): Contribuiçâo para o conhecimiento dos grandes mamíferos do Plistocénico superior de Portugal, Oeiras.

- Castaños, P. (1987): “Los carnívoros prehistóricos de Vizcaya”, Kobie (Serie Paleoantropología), 16, 7-76.

- Castaños, J. et Castaños, P. (2017): “Estudio de la fauna de macromamíferos del yacimiento de Praileaitz I (Deba, Gipuzkoa)”, Munibe Monographs, Anthropology and Archaeology Series 1, 221-265.

- Castaños, J., Castaños, P., Suárez-Bilbao, A., Iriarte-Chiapusso, M.J., Arrizabalaga, A. and Murelaga, X. (2019): “A large mammal assemblage during MIS 5c: Artazu VII (Arrasate, northern Iberian Peninsula)”, Historical Biology, 31, 6, 731-747.

- Cervera, J., García, N. et Arsuaga, J.L. (1999): “Los carnívoros del yacimiento mesopleistoceno de galería (Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos)”, in: Díez, J.C., Rosas, A., Carbonell, E., ed., Atapuerca: ocupaciones humanas y paleoecología del yacimiento de Galería, 175-188.

- Cohen, J. A. (1978): “Cuon alpinus”, Mammalian species, 100, 1-3.

- Crégut-Bonnoure, E. (1996): “Famille des Canidae”, in: Guérin, C. & Patou-Mathis, M., ed., Les grands mammifères plio-pleistocènes d’Europe, 156-166.

- Daura, J., Sanz, M., García, N., Allué, E., Vaquero, M., Fierro, E., Carrión, J.S., López-García, J.M., Blain, H.A., Sánchez-Marco, A., Valls, C., Albert, R.M., Fornós, J.J., Julià, R., Fullola, J.M. and Zilhao, J. (2013): “Terrasses de la Riera dels Canyars (Gavà, Barcelona): the landscape of Heinrich Stadial 4 north of the ‘Ebro frontier’ and implications for modern human dispersal into Iberia”, Quaternary Science Reviews, 60, 26-48.

- Dufour, R. (1989): Les carnivores pléistocènes de la caverne de Malarnaud (Ariège), Muséum d’Histoire naturelle de Bordeaux.

- Durbin, L. S., Venkataraman, A., Hedges, S. and Duckworh, W. (2004): “Dhole. Cuon alpinus Pallas, 1811”, in: Sillero-Zubiri C., Hoffmann M. & Macdonald D.W., ed., Canids: Foxes, Wolves, Jackals and Dogs. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, 210-218. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235249360_Dhole_Cuon_alpinus

- Fernández Peris, J. (2007): “La Cova del Bolomor (Tavernes de la Valldigna, Valencia). Las industrias líticas del Pleistoceno medio en el ámbito del Mediterráneo peninsular”, Serie de Trabajos Varios del SIP, 108, Valencia.

- García, N., ed. (2003): Osos y otros carnívoros de la Sierra de Atapuerca, Fundación Oso de Asturias, Oviedo.

- Geraads, D. (1995): “Carnívoros musterienses de la Cueva de Zafarraya (Málaga)”, Cuaternario y Geomorfología, 9 (3-4), 51-57.

- Holliday, J.A. and Steppan, S.J. (2004): “Evolution of hypercarnivory: the effect of specialization on morphological and taxonomic diversity”. Paleobiology, 30 (1), 108-128.

- Kamler, J.F., Songsasen, N., Jenks, K., Srivathsa, A., Sheng, L. and Kunkel, K. (2015): Cuon alpinus. The IUCN Red list of threatened species 2015. E.T5953A72477893.

- Mallye, J.B., Costamagno, S., Boudadi-Maligne, M., Prucca, A., Lauroulandie, V., Thiébaut, C. and Mourre, V. (2012): “Dhole (Cuon alpinus) as a bone accumulator and new taphonomic agent? The case of Noisetier Cave (French Pyrenees)”, Journal of Taphonomy, 10 (3-4), 317-347.

- Morales, J.V., Sanchis, A., Real, C., Pérez Ripoll, M., Aura, J.E. and Villaverde, V. (2012): “Evidences of interaction Homo–Cuon in three Upper Pleistocene sites of the Iberian Mediterranean central region”, Journal of Taphonomy, 10 (3-4), 463-476.

- Pérez Ripoll, M., Morales Pérez, J. V., Sanchis Serra, A., Aura Tortosa, J. E. and Sarrión Montañana, I. (2010): “Presence of the genus Cuon in upper Pleistocene and initial Holocene sites of the Iberian Peninsula: new remains identified in archaeological contexts of the Mediterranean region”, Journal of Archaeological Science, 37 (3), 437-450.

- Rasilla, M. de la, Santamaría, D. et Rodríguez, V. (2014): “Llonin”, in: Sala, R., Carbonell, E., Bermúdez de Castro, J.M. & Arsuaga, J.L., ed., Los cazadores recolectores del Pleistoceno y del Holoceno en Iberia y el Estrecho de Gibraltar: Estado actual del conocimiento del registro arqueológico, Burgos, 663-665.

- Richard, M., Falguères, C., Pons-Branchu, E., Foliot, L., Guillem, P.M., Martínez-Valle, R., Eixea, A. et Villaverde, V. (2019): “ESR/U-series chronology of early Neanderthal occupations of Cova Negra (Valencia, Spain)”, Quaternary Geochronology, 49, 283-290.

- Rohland, N., Pollack, J.L., Nagel, D., Beauval, C., Airvaux, J., Pääbo, S., Hofreiter, M. (2005): “The Population History of Extant and Extinct Hyenas”, Molecular Biology and Evolution, 22 (12), 2435–2443.

- Sanchis, A., Real, C., Sauqué, V., Núñez-Lahuerta, C., Égüez, N., Tormo, C., Pérez Ripoll, M., Carrión Marco, Y., Duarte, E. et De La Rasilla, M. (2019): “Neanderthal and carnivore activities at Llonin Cave, Asturias, Northern Iberian Peninsula: Faunal study of the Mousterian levels (MIS 3)”, Comptes Rendus Palevol, 18 (1), 113-141.

- Sanchis, A. et Villaverde, V. (in press): “Restos postcraneales de Cuon en el Pleistoceno superior (MIS 3) de la Cova de les Malladetes (Barx, Valencia)”, Saguntum-Extra, 20. Homenaje al profesor Manuel Pérez Ripoll, 181-196.

- Sarrión, I. (1984): “Nota preliminar sobre yacimientos paleontológicos pleistocénicos en la Ribera Baixa. Valencia”, Cuadernos de Geografía, 35, 163-174.

- Sarrión, I. (1990): “El yacimiento del Pleistoceno medio de la Cova del Corb (Ondara-Alicante)”, Archivo de Prehistoria Levantina, 20, 43-78.

- Schlosser, M. (1923): “Neue funde von fossilen Wirbeltieren in Spanien”, Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie, 657-662.

- Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2009): “Family Canidae (Dogs)”, in: Mittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B. & Wilson, E., ed., Handbook of the Mammals of the World. 1. Carnivores, Barcelona, 352-447.

- Sommer, R. et Benecke, N. (2005): “Late Pleistocene and early Holocene history of the canid fauna of Europe (Canidae)”, Mamm. Biol. Z. Säugetierkd, 70 (4), 227-241.

- Van Valkenburgh, B. (1989): “Carnivore dental adaptations and diet: a study of trophic diversity within guilds”, in: Gittleman, J.L., ed., Carnivore Behavior, Ecology, and Evolution, Boston, 410-436. doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-4716-4_16

- Van Valkenburgh, B. (1991): “Iterative evolution of hypercarnivory in canids (Mammalia: Carnivora): evolutionary interactions among sympatric predators”, Paleobiology, 17 (4), 340-362.

- Villaverde, V., Guillem, P., Martínez, R. et Eixea, A. (2014): “Cova Negra”, in: Sala, R., Carbonell, E., Bermúdez de Castro, J.M. & Arsuaga, J.L., ed., Los cazadores recolectores del Pleistoceno y del Holoceno en Iberia y el Estrecho de Gibraltar: Estado actual del conocimiento del registro arqueológico, Burgos, 361-369.

- Wißing, C., Rougier, H., Baumann, C., Comeyne, A., Crevecoeur, I., Drucker, D. G., Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S., Germonpré, M., Gómez-Olivencia, A., Krause, J., Matthies, T., Naito, Y.I., Posth, C., Semal, P., Street, M. and Bocherens, H. (2019): “Stable isotopes reveal patterns of diet and mobility in the last Neandertals and first modern humans in Europe”, Scientific Reports, 9, 4433.

Notes

- Cohen 1978; Durbin et al. 2004; Kamler et al. 2015; Sillero-Zubiri 2009.

- Holliday & Steppan 2004; Van Valkenburgh 1989, 1991.

- In this text, the lower teeth are indicated by a lower-case letter and the upper teeth by an upper-case letter.

- Bonifay 1971; Bourguignat 1875; Crégut-Bonnoure 1996; Van Valkenburgh 1991.

- Brugal & Boudadi-Maligne 2011; Dufour 1989; Sommer & Benecke 2005.

- Schlosser 1923.

- Arceredillo et al. 2013; Brugal 2004; García 2003.

- Altuna 1973, 1981, 1983, 1986, 1990; Barroso et al. 2006; Blasco 1995; Cardoso 1993; Castaños 1987; Castaños & Castaños 2017; Castaños et al. 2019; Daura et al. 2013; Geraads 1995; Morales et al. 2012; Pérez Ripoll et al. 2010.

- Morales et al. 2012; Pérez Ripoll et al. 2010.

- Brugal & Fosse 2004; Mallye et al. 2012; Morales et al. 2012.

- Bonifay 1971; Brugal & Boudadi-Maligne 2011; Crégut-Bonnoure 1996.

- Sanchis et al. in preparation.

- Adam 1959.

- Bonifay 1971.

- Brugal & Boudadi-Maligne 2011.

- Holliday & Steppan 2004; Van Valkenburgh 1989, 1991.

- Pérez Ripoll et al. 2010.

- Sanchis et al. in preparation.

- C. a. lepturus and C. a. javanicus/ sumatrensis are indeed recognised as a subspecies of a very small dhole. Therefore, comparisons made between these extant subspecies and the European fossil dhole should be interpreted with caution.

- Altuna 1972.

- Sarrión 1984, 1990.

- Boudadi-Maligne 2010.

- The choice of p4, m1, P4 and M1 responds to both conservation and functional reasons, due to the presence of morphological and size characters related to a certain degree of evolution. Due to the lack of references for m2 in the fossil record of Cuon in the Iberian Peninsula, it has not been included. The radius is the best represented dhole postcranial bone in the Iberian fossil record.

- Altuna 1983; Bonifay 1971; Brugal & Boudadi-Maligne 2011; Van Valkenburgh 1989, 1991.

- Sarrión 1984; unpublished material.

- Boudadi-Maligne 2010.

- Sarrión 1984, 1990; unpublished material.

- Altuna 1972.

- Boudadi-Maligne 2010.

- Altuna 1972.

- Boudadi-Maligne 2010.

- Altuna 1972.

- Boudadi-Maligne 2010.

- Altuna 1983.

- Pérez Ripoll et al. 2010.

- Unpublished.

- Altuna 1983.

- Sanchis & Villaverde in press.

- Richard et al. 2019; Villaverde et al. 2014.

- Fernández Peris 2007.

- Rasilla et al. 2014; Sanchis et al. 2019.

- Pérez Ripoll et al. 2010.

- Richard et al. 2019.

- Sanchis et al. in preparation.

- Sanchis et al. in preparation.

- Brugal & Boudadi-Maligne 2011.

- Bonifay 1971.

- Cervera et al. 1999; García 2003.

- Altuna 1983.

- Unpublished data.

- Boudadi-Maligne 2010; Brugal & Boudadi-Maligne 2011.

- Altuna 1973.

- Bourguignat 1875.

- García 2003.

- e.g. Barnett et al. 2009.

- Rohland et al. 2005.

- Cf. Wißing et al. 2019.