This paper presents an overview of research in the hinterland of the northern Adriatic, reaching as far as the south-eastern Alpine region and the Pannonian Plain. The western and northern parts of this region are predominantly mountainous in character, strongly marked by the Julian Alps. In the area of the so-called Postojna Gate mountain pass, it borders the chain of the Dinaric Alps, a dividing line between the Mediterranean and continental world. Towards the east, the Alps turn into the hilly subalpine region and further on onto the Pannonian Plain.

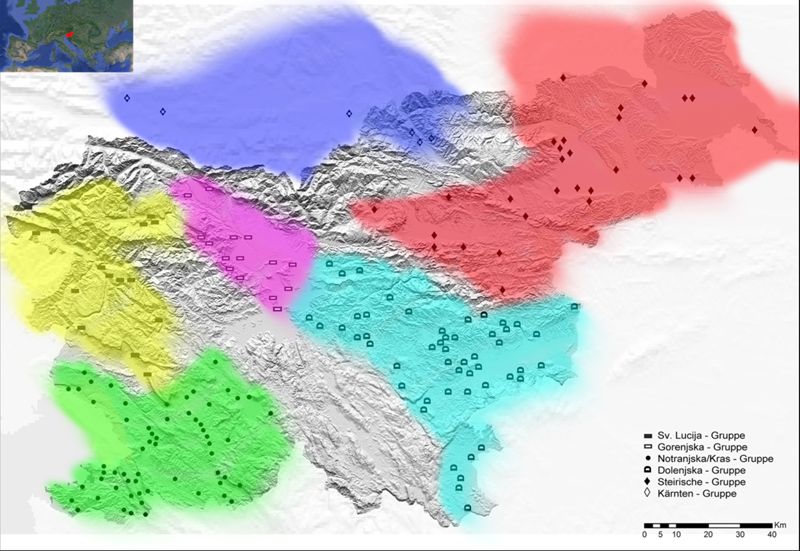

In the Early Iron Age, this varied geography was mirrored by its cultural diversity, expressed in differentiated settlement patterns and burial rites. Several new cultural groups developed in the region in the Iron Age (Fig. 1); they partly followed the traditions of the preceding Urnfield culture, while, to a certain extent at least, they evolved under the influence of a new military ideology, which spread from the Pontus region to the Atlantic Ocean and is known under the term “Hallstatt culture”. These cultural groups differ in their way of life and have different settlement types and patterns as well as diverse burial rites and practices. They possess a varied material culture, different attires and costume, weapons and status symbols; in short, they clearly differ in their identity. Here, I intend to discuss the main characteristics of the three most important and best researched cultural groups in the region – namely the Sv. Lucija/St Lucia or Posočje group, the Lower Carniola or Dolenjska group, and the Styrian or Styrian-Pannonian group, also known as the Kleinklein – Martijanec – Kaptol group and consider the relationships and interactions among and between them. The other two or three groups present in the region, such as the Notranjska group (also comprising the Karst/Kras region), the Gorenjska group and the Breg-Frög group in Carinthia will be mentioned only in passing when making comparisons between our entities. The development of the major groups took place from their formative phase between the ninth and eighth century BC to their heyday, in the seventh and sixthcentury BC. As for their decline, their timing varies, for different reasons, including the invasions of the Scythians in the sixth century BC (Teržan 1998) on the one hand, and on the other hand the Celtic invasions in the fourth and third centuries BC, which resulted in the spread of the La Tène culture (Gabrovec 1966b; Teržan 2014a; Teržan 2015; Teržan & Črešnar 2014, 721-725, fig. 43, 44).

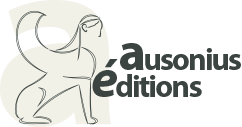

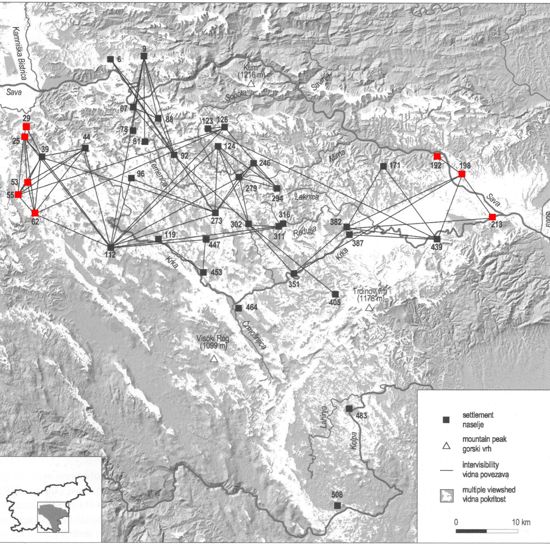

The area of western Slovenia, or more precisely the region of Posočje (the valley of the river Soča), was occupied by the St Lucia group (Fig. 1, yellow). The most prominent sites of this group are Most na Soči, formerly named Sv. Lucija/St Lucia (Gabrovec & Svoljšak 1983; Teržan et al. 1985-1986), the site of Kobarid (Gabrovec 1976; Mlinar & Gerbec 2011; Kruh 2014) and Tolmin (Svoljšak & Pogačnik 2001-2002). The settlements were usually positioned on strategic and naturally well protected sites at river confluences, as is the case of Most na Soči, located above the canyon-like confluence of the rivers Idrijca and Soča (Mlinar 2002, fig. 1, 3, 8-10; Svoljšak & Dular 2016, fig. 1-3, 5). The position of the Kobarid settlement is similar, controlling the main communication route between the Soča and Nadiža/Natisone valleys, connecting the Posočje region over the Friuli plain with the Veneto – the area of the Este culture (Mlinar & Gerbec 2011, fig. 1-2). According to Drago Svoljšak’s research, the entire area of the St Lucia group was organized so as to be a well-protected territory (Fig. 2). The central settlements of Most na Soči and Kobarid were surrounded by smaller outposts, strategically located at the entrances to the main valleys in order to control the only possible access points leading to the core of the region (Svoljšak 1983; Svoljšak 2001).

Excavations at the site of Most na Soči revealed the settlement’s proto-urban layout, with a clear division of residential and cult areas and separate craft and trading quarters (Fig. 3) (Gabrovec & Svoljšak 1983, 17-21, fig. 18-19; Svoljšak 2001; Svoljšak & Dular 2016, app. 1). The importance of the settlement as a trading centre is indicated by imports such as Attic and/or Ionian pottery (Marchesetti 1893/1993, pl. 6: 9; Frey 1971, 364, fig. 11: 5-15, pl. 2: 1; Žbona-Trkman & Svoljšak 1981, fig. 17; Teržan et al. 1984-1985, 187, 188, pl. 102: 9; 104: 13; 288: 1; Mlinar 2002, 28-30, fig. 25; Svoljšak & Dular 2016, 70, 235, pl. 25: 1) and an Etruscan wine flagon (Vitri 1980). Also indicative are glass mask pendants in the form of a male human head (Gesichtsperlen) and other glass beads, including layered eye-beads (Schichtaugenperlen) and compound eye-beads (Perlen mit zusammengesetzten Augen) of Phoenician or Carthaginian provenance (Marchesetti 1893/1993, pl. 29: 8-9; Teržan et al. 1984-1985, pl. 127: 4, 5, 8; Svoljšak & Dular 2016, pl. 23: 8; 62: 1; 89: 19; Haevernick 1977/1981, 310, 343, fig. 5: 468; Haevernick 1972/1981, 233–244, pl. 2: 1; Haevernick 1974/1981, 261–264, pl. 1: 6-7; Kunter 1995, 78-85, 191-198, 357-359, pl. 2: 23, 25, 55; 5: 20-21; 9: 2; 29: 9; maps 12, 14). These outstanding items clearly come from the south and were found in both the settlement and in graves. Moreover, there are clear indications that trade with rather distant regions to the north was also lively, for example with sites of the western Hallstatt cultural zone, documented by exports to and imports from the St Lucia group (Frey 1971; Krause 2002, 502-503, fig. 18; Balzer 2010, 30-32, fig. 4-5).

The St Lucia group, in particular the settlement at Most na Soči and its burial ground, where so far more than 7000 graves have been discovered (Teržan et al. 1984-1985; Marchesetti 1893/1993), grew in strength from the eighth century BC onwards, reached its peak in the seventh to fifth century BC, and then fell into decline (Teržan & Trampuž 1973; Bergonzi et al. 1981, 184-252; Gabrovec 1987; Parzinger 1988, 8-27, pl. 5-25).

The deceased were buried in flat cremation cemeteries, the burial rite remaining practically unaltered throughout the entire existence of the settlement of Most na Soči. Graves were usually marked with stone slabs (Marchesetti 1885/1993, pl. 10; Teržan et al. 1984-1985; Svoljšak & Pogačnik 2001-2002, 14-15, fig. 3-4). In the earlier period the predominant rite was cremation burial without an urn but later burials in urns became more common, especially in richer graves. Grave goods consist of fairly standardized and modest assemblages of pottery or jewellery items, regardless of male or female attire. Among the most typical items in the earlier period are spectacle fibulae of St Lucia type (Pabst 2012, 88-91, 209-220, tab. 16-17) as well as two-looped bow fibulae with knobs (Gabrovec 1970, 28, map IX; tab. 11: 2; 13: 2; Teržan & Trampuž 1973, 424-426, map 2; 1; 3; pl. 5: 5; 8:14), whereas later, bow fibulae of the St Lucia type are common. These fibulae represent a particular type of jewellery, exclusive to the attire of the St Lucia group, and can therefore be taken as a special symbol of its group identity (Teržan & Trampuž 1973, 428-434, pl. 1, map 4: 1, pl. 11: 3, 18; 12: 3-4; 13: 2, 8; 16: 1). Weapons, on the other hand, do not appear in standard burial assemblages; they are known only in exceptional cases, particularly in the later phases of the cemetery and clearly indicate the special status of male warriors (Teržan & Trampuž 1973, 434, Priloga 1, fig. 4: 3; pl. 20; Teržan 2009, 94, fig. 11).

The prestigious grave goods from Most na Soči primarily consist of bronze vessels, such as buckets, situlae, cists etc.

(Jereb 2016), and multi-coloured small glass cups (Teržan et al. 1984-1985, 42, pl. 104: 12; 260: 11; 264: 7; Marchesetti 1893/1993, pl. 8-9; Haevernick 1958/1981) as well as imported Greek pottery and some outstanding jewellery pieces, especially those made of amber. All these objects clearly indicate the existence of an upper class and hence point to social stratification in the St Lucia community.

In contrast to the settlement type of the St Lucia group, hillforts are characteristic of the Karst/Kras region, where they are dominant (Marchesetti 1903/1981; Flego & Rupel 1993; Slapšak 1995). These hillforts extend south of the territory of the St Lucia group and the Vipava valley, along the Gulf of Trieste and further in its hinterland up to the northern part of the Istrian peninsula (Fig. 1: green). The hillforts were fortified with impressive defensive walls, built in drystone (Fig. 4). Without doubt, they can be related to the masonry tradition of the Bronze Age Castellieri culture (Hänsel et al. 2015).

The excavations and fieldwork we conducted a few years ago managed to show that along the northern mountain range of the Kras high plateau, which is also the northern border of the so-called Notranjska-Kras group (Guštin 1973; Guštin 1979; Gabrovec 1987), several watchtowers or small hillforts had been built at regular intervals of about 3 to 5 km (Fig. 5). A good example is the newly excavated tower on the hill of Ostri vrh near Štanjel, which was constructed in a drystone technique combined with timber, indicated by a series of postholes and niches for posts. The latter appear along both the inner and outer face of the wall and at roughly regular intervals of around 1.2 to 2 m (Fig. 6 A-C) (Teržan & Turk 2005; Turk & Jereb 2006, 12-15, fig. 2-5; Teržan & Turk 2014).

We contend that these towers or small hillforts were used to control a frontier and represented a defensive boundary delimiting the territory of the Kras community towards the Vipava valley in the north, along the so called “Amber route”, which ran through central Europe, linking Italy with the Baltic. The fortified line also delimits the area from the territory of the St Lucia group further north (Fig. 1; 5). According to the radiocarbon dates obtained from charcoal samples taken from postholes of the tower at Ostri vrh, these outposts were built and then maintained during the later Hallstatt period in the sixth and fifth centuries BC, if not earlier (Fig. 6 D). In this period, at the latest, we can assume that the Notranjska-Kras group was also organized territorially and possessed its own defensive system.

The south-eastern part of Slovenia was occupied by the Dolenjska cultural group, whose territory comprised the regions of Dolenjska or Lower Carniola and Bela krajina or White Carniola as well as the Lower Sava valley up to the so-called “Brežice Gates” and the Gorjanci Hills (Fig. 1, light blue). The region is predominantly hilly, and was densely populated with hilltop settlements that were usually well fortified, either with stone walls of the so-called Stična type or with earthen ramparts and palisades. Characteristic for the defensive system of the Stična type are drystone walls with additional timber construction (Fig. 7 B-C). The outer face of the wall had an earthen rampart, which was partly revetted with smaller stones, while a ditch lay at its base (Gabrovec 1994, 144-165; Dular & Tecco Hvala 2007, 70-104).

The best-investigated Iron Age settlement in the Dolenjska region so far is Cvinger above Vir near Stična. The settlement investigated by Stane Gabrovec stands out from other known sites for its size (Dular & Tecco Hvala 2007, 191–195, fig. 110, 113) as well as its fortifications (Fig. 7). It was undoubtedly the region’s central place, an interpretation supported by the fact that the hillfort was planned, involving the erection of defensive walls several kilometres long in a single building operation. Such a feat clearly points to a single act of foundation that can be dated to the eighth century BC and marks the formative phase of the Dolenjska Hallstatt community (Gabrovec 1994).

There are also clear indications that several other hillforts were founded at approximately the same time, that is, in the late ninth or during the eighth century BC. These settlements remained inhabited throughout almost the entire period of existence of the Dolenjska group, until its end in the late fourth century BC (Dular & Tecco Hvala 2007; Teržan & Črešnar 2014, 721–725), when it was overpowered by a Celtic invasion from the east.

In the Early Iron Age, the hillforts had a fairly good visual control over their surrounding territories. The same was also true for the intervisibility between individual hillforts; this improved as the density of hillforts increased in the Late Hallstatt period (Fig. 8). The entire territory of the Dolenjska group was therefore closely interconnected through a visual control and communication network, which would also imply a common defence system.

A major characteristic of the Dolenjska Hallstatt community is its specific type of cemeteries and burial rites. In contrast to the flat cemeteries of the preceding Urnfield culture and of the contemporary groups of St Lucia and Notranjska-Kras, the cemeteries of the Dolenjska group feature a new type of monument, the tumulus (Fig. 9). The barrow cemeteries cover very large areas and are usually in several clusters, positioned around the fortified hilltop settlement and spread along the main roads that led to or from the settlement. They can consist of several dozens or even more than one hundred tumuli, as at Stična (Fig. 7 A), Šmarjeta, or Novo Mesto (Dular & Tecco Hvala 2007, fig. 89-109). A single tumulus represents the burial site of an extended family or clan and generally contains numerous burials, which can reach several hundred, as is the case of the large tumuli at Stična (Wells 1981, 45-89; Gabrovec 2006; Gabrovec & Teržan 2008) or at Magdalenska gora (Hencken 1978; Tecco Hvala et al. 2004; Tecco Hvala 2012). In an early stage, some graves in the tumuli could still be cremation burials, but inhumation burials prevailed relatively quickly throughout the entire area of the Dolenjska group.

The internal structure of the tumulus is strictly standardized: the centre is occupied either by the grave of the founder of the family or clan (Fig. 9A) or it is left empty as a kind of cenotaph or memorial to a mythical ancestor. The latter is especially true for the tumuli of the late Hallstatt (Ha D) phase in Novo Mesto (Knez 1986, pl. 62-65; Teržan 2008, 192–224). All subsequent graves are arranged concentrically and tangentially around this central part, generation after generation and often in several circles. Through time, these burials increasingly emphasize the importance and status of the first individual buried. Indeed, the position and orientation of the individual graves within the tumulus depend not only on the factors mentioned above, but also refer to the celestial sphere and cardinal points. Judging from the orientation of the graves, the tumuli must have originally been divided into two halves, eastern and western (or northern and southern). This dividing line then separated the graves according to their orientation, which ran either clockwise or anticlockwise (Fig. 9A).

It seems that the position of the grave within a tumulus was also determined by the sex, age and status of the deceased individual within the social hierarchy. The tumuli thus reveal a community with a very complex social structure, organized according to a dualistic principle. This can most effectively be demonstrated in the large tumulus of Stična (Fig. 9A): those buried on the eastern side of the tumulus, where the sun rises, are warrior-horsemen accompanied by their retinue or entourage, as well as women of the highest rank. On the western side, other interments contain mostly women of different categories and men of lower social standing (Teržan 2008, 233–262, fig. 15-27).

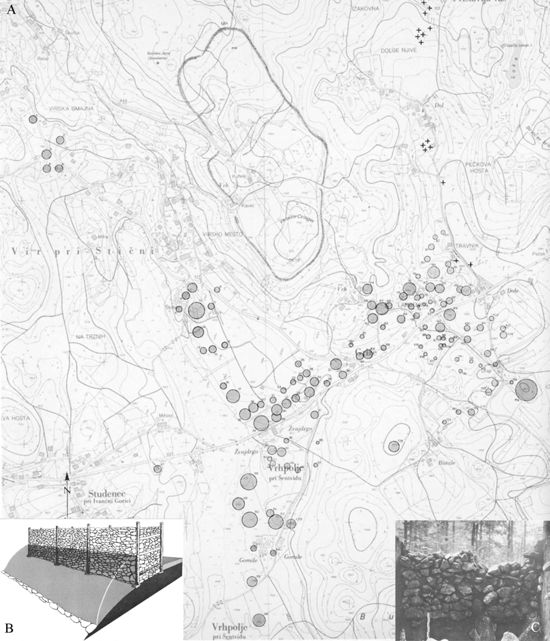

It should be emphasized that burial customs in the Dolenjska community clearly show a society with a distinctive military organization. Offensive weapons, such as swords, axes, spears or arrows, are considered mandatory grave goods for male burials (Teržan 1985) and appear regularly. On the other hand, prestigious armour, be it cuirasses or helmets (Gabrovec 1960; Gabrovec 1962-1963; Egg 1986; Gabrovec 2006, pl. 135; 207; 212; Born 2008, 137-158), as well as sacrificed horses and horse gear signal leading warrior-horsemen (Guštin & Teržan 1977, 77-80, map 1, pl. 1-4; Dular 2007; Teržan 2011a; Teržan 2014b), the top of the military elite (Dular & Tecco Hvala 2007, 239-245, fig. 138-141; Teržan 2008, 267-272, 310-325).

The standardized sets of weapons suggest that the male population was divided into six classes in the Late Hallstatt period from the sixth to the fourth century BC, five of which can be ranked as warrior classes (Fig. 10). This implies a strictly military organization of a society led by a horseman-commander-king. An impression of such a social organization can also be gained from the iconography that features in situla art (Teržan 1985, fig. 1-2, 5-7, 12–13, 15-19; Teržan 1997, 661–663, fig. 6; Teržan 2014a; Teržan 2015, 6-69, fig. 1-4).

The Styrian-Pannonian group is characteristic of the eastern Hallstatt culture (Fig. 1, red). As the name suggests, the group extends across Styria (in Slovenia and Austria) from the Savinja valley in the south, across the basins of the rivers Drava/Drau, Mura/Mur and Raba/Raab, all the way to the Pannonian Plain in the east. In the Pannonian Plain, this group is labelled differently, due to different political and historical backgrounds, but essentially it refers to the same cultural phenomenon (Dobiat 1980; Vinski-Gasparini 1987; Patek 1993; Teržan 1990, 121-209, fig. 56).

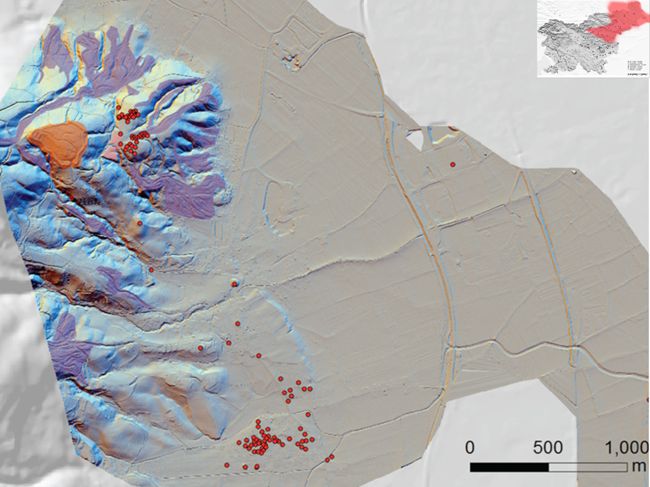

The most famous sites of this group are Kleinklein and Strettweg in Austria, the latter the subject of quite recent publications (Egg 1996; Egg & Kramer 2013; Egg & Kramer 2016; Tiefengraber et al. 2013). Here, I shall limit myself to some general remarks about the characteristics of the group and to the presentation of new research at the site of Poštela, where geophysical and LiDAR surveys have been conducted.

With the beginning of the Early Iron Age, a change in the settlement pattern can be observed in this region, too. The sites are no longer located in the lowlands, but sited predominantly on high ground for strategic reasons. Recent excavations have shown that the hilltop settlements are mostly fortified with earthen ramparts and timber palisades and surrounded by ditches. Such fortifications are attested, for example, at Poštela (Teržan 1990, 25-30, 256-306, fig. 5, 9-11, 35-39) or the Burgstallkogel near Kleinklein (Dobiat 1980) and clearly differ from the Dolenjska and Notranjska-Kras groups.

The second characteristic of this group is that the cremated remains of the deceased were buried under tumuli. Here, the cremation rite doubtlessly belongs to the tradition of the preceding Urnfield culture, but the tumulus as a funerary marker and monument surely represents a significant innovation. Vast barrow cemeteries are usually arranged in clusters, located quite close to the hilltop settlement and often at its base (Fig. 11) (Dobiat 1980, map 1; Mele 2012; Teržan 1990, 256-257, fig. 1-2; 349, fig. 94; 355, fig. 99 etc.; Tiefengraber et al. 2013). Unlike the tumuli of the Dolenjska region – containing the inhumation burials of all the members of an extended family or clan in the same tumulus – the Styrian-Pannonian tumuli contain mostly just the cremation burials of a single individual quite frequently accompanied by his or her retinue of one or more persons who were most probably sacrificed on this occasion. Burial chambers, made of stone and/or wood, are usually located in the centre of these tumuli. The chambers are generally square or rectangular in plan and their orientation depends on the cardinal points; a few rare tombs with a round plan are also known (Teržan 1990, 55-58, 316-337, 351-352, 359-363; Strmčnik & Teržan 2004, 221-223, fig. 3-5; Teržan & Črešnar 2015, fig. 2, 5).

Very large tumuli, where the burial chamber is often complemented by a dromos (a passage lined with walls and a paved floor) have also been recorded (Dobiat 1980, 53-63, fig. 5-6; Egg 1994, 63-66, fig. 7; Egg & Kramer 2013; Teržan 1990, 323, 335-336, fig. 69, 83-85; 103-104; Šimek 1998, 493-498, fig. 1-3; Šimek 2004, 102-127, fig. 24, 39-41; Potrebica 2013, 184-185, fig. 96; Tiefengraber et al. 2013, 30-42, fig. 13, 19-21).

The typical grave goods found in the tumuli are predominantly a rich and varied assemblage of pottery as well as bronze vessels, ranging from storage containers to eating and drinking sets, which are usually intended for several persons, i.e. for symposia. Male graves often contain weapons, such as swords, spears or axes and horse gear, while the exceptional warrior graves also include helmets, cuirasses, shields and sometimes even sacrificed horses. This indicates that here too the hierarchy was headed by warrior-horsemen (Dobiat 1980; Teržan 1990, fig. 14, 27-32, 34, 39, 41-43, 48; Egg 1996; Egg & Kramer 2013 and 2016; Teržan 2011a).

There are clearly differences between the cultural groups under discussion, reflected in the attributes that demarcate them, be it the settlement types, the construction of their defensive walls, the specific burial rite (cremation or inhumation, flat cemeteries or barrow cemeteries) or the composition of the grave goods (with or without weapons, with or without pottery sets, etc.). Yet, despite these differences, and irrespective of our thesis that the groups were territorially organized and had their own defence systems, our three major groups were obviously imbued with a common ideology.

The fundamental structure of society and its ideology, not just that of the Styrian-Pannonian group but of the eastern Hallstatt culture in general, manifests itself in the Strettweg wagon (Fig. 12) (Egg 1996). The wagon has at its centre the image of a goddess endowed with a life-giving force (carried in the bowl) and other powers. The cult of this goddess involves continuing and cyclical ritual activities, such as the sacrifice of animals and the “holy marriage”, which were of major significance for the maintenance of the social order. The figure of the Strettweg goddess is guarded by elite mounted warriors, a fact worth emphasizing here (Teržan 2001; Teržan 2011b). The latter clearly regarded themselves as divine representatives, as rulers and kings. This belief is also materialized in the prestigious graves on the far margins of the Hallstatt culture which represent another facet of the “holy world order” expressed in the complex iconography of the Strettweg wagon.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank my colleague Miha Kunstelj for an initial translation of my text, Alenka Dovč for translation into French and Manca Vinazza for the layout of the figures.

References

- Bandelli, G. and Montagnari Kokelj, E., ed. (2005): Carlo Marchesetti e i castellieri 1903-2003, Fonti e studi per la Storia della Venezia Giulia, Serie seconda: Studi 9, Trieste.

- Balzer, I. (2010): “Der Breisacher Münsterberg zwischen Mont Lassois und Most na Soči”, in: Jerem et al., ed. 2010, 27-39.

- Becker, C., Dunkelmann, M.-L., Metzner-Nebelsick, C., Peter-Röcher, H., Roeder, M. and Teržan, B., ed. (1997): Χρόνος. Beiträge zur Prähistorischen Archäologie zwischen Nord- und Südosteuropa. Festschrift für Bernhard Hänsel, Internationale Archäologie. Studia honoraria 1, Espelkamp.

- Bergonzi, G., Boiardi, A., Pascucci, P. and Renzi, T. (1981): “Corredi funebri e gruppi sociali ad Este e S. Lucia”, in: Peroni, ed. 1981, 91-252.

- Blečić M., Črešnar M., Hänsel B., Hellmuth A., Kaiser E. and Metzner-Nebelsick C., ed. (2007): Scripta praehistorica in honorem Biba Teržan, Situla, Narodni muzej Slovenije 44, Ljubljana.

- Born, H. (2008): “‘Cesarjeva nova oblačila’. Restavriranje in tehnika izdelave stiškega oklepa iz gomile 52/ ‘Des Kaisers neue Kleider’. Restaurierung und Herstellungstechnik des Stična Brustpanzers aus Grabhügel 52”, in: Gabrovec & Teržan 2008, 137-158.

- Casini, S., ed. (2011): “Il filo del tempo”. Studi di preistoria e protostoria in onore di Raffaele Carlo de Marinis, Notizie Archaeologiche Bergomensi 19, Bergamo.

- Dobiat, C. (1980): Das hallstattzeitliche Gräberfeld von Kleinklein und seine Keramik, Schild von Steier Beiheft 1, Graz.

- Dobiat, C. (1990): Der Burgstallkogel bei Kleinklein I. Die Ausgrabungen der Jahre 1982 und 1984, Marburger Studien zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte 13, Marburg.

- Dular, J. (2007): “Pferdegräber und Pferdebestattungen in der hallstattzeitlichen Dolenjsko-Gruppe”, in: Blečić et al., ed. 2007, 737-752.

- Dular J. and Tecco Hvala S. (2007): South-Eastern Slovenia in the Early Iron Age. Settlement – Economy – Society, Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 12, Ljubljana.

- Egg, M. (1986): Italische Helme. Studien zu den ältereisenzeitlichen Helme Italiens und der Alpen I-II, Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz, Monographien 11, Mainz.

- Egg, M. (1996): “Zu den Fürstengräbern im Osthallstattkreis”, in: Jerem & Lippert, ed. 1996, 53-86.

- Egg, M. (1996): Das hallstattzeitliche Fürstengrab von Strettweg bei Judenburg in der Obersteiermark, Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz, Monographien 37, Mainz.

- Egg, M. and Kramer, D. (2013): Die hallstattzeitlichen Fürstengräber von Kleinklein in der Steiermark: Kröllkogel, Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz, Monographien 110, Mainz.

- Egg, M. and Kramer, D. (2016): Die hallstattzeitlichen Fürstengräber von Kleinklein in der Steiermark: die beiden Hartnermichelkogel und der Pommerkogel, Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz, Monographien 125, Mainz.

- Flego, S. and Rupel, L. (1993): Prazgodovinska gradišča Tržaške pokrajine, Trst.

- Frey, O.-H. (1971): “Fibeln vom westhallstättischen Typus aus dem Gebiet südlich der Alpen. Zum Problem der keltischen Wanderung”, in: Raccolta di studi di Antichità in onore del Prof. Aristide Calderini, Como, 355-386

- Gabrovec, S. (1960): “Grob z oklepom iz Novega mesta/ Panzergrab von Novo mesto”, Situla, Ljubljana, 1, 27-79.

- Gabrovec, S. (1962-1963): “Halštatske čelade jugovzhodnoalpskega kroga/ Die hallstättischen Helme des südostalpinen Kreises”, Arheološki vestnik, Ljubljana, 13-14, 293-347.

- Gabrovec, S. (1964-1965): “Halštatska kultura v Sloveniji”, Arheološki vestnik, Ljubljana, 15-16, 21-63.

- Gabrovec, S. (1966a): “Zur Hallstattzeit in Slowenien”, Germania, 44, 1-48.

- Gabrovec, S. (1966b): “Srednjelatensko obdobje v Sloveniji/ Zur Mittellatènezeit in Slowenien”, Arheološki vestnik, 17, 169-242.

- Gabrovec, S. (1970): “Dvozankaste ločne fibule. Doprinos k problematici začetka železne dobe na Balkanu in v jugovzhodnih Alpah/ Die zweischleifige Bogenfibeln. Ein Beitrag zum Beginn der Hallstattzeit am Balkan und in den Südostalpen”, Godišnjak/ Jahrbuch, 8, Centar za balkanološka ispitivanja, Sarajevo, 5-65.

- Gabrovec, S. (1976): “Železnodobna nekropola v Kobaridu”, Goriški letnik, 3, 44-64.

- Gabrovec, S. (1987): “Jugoistočna alpska regija sa zapadnom Panonijom: Dolenjska grupa, Svetolucijska grupa, Notranjska grupa, Ljubljanska grupa”, in: Praistorija jugoslavenskih zemalja 5: Željezno doba, Sarajevo, 25-181.

- Gabrovec, S. (1994): Stična I. Naselbinska izkopavanja/ Siedlungsausgrabungen, Catalogi et monographiae, Narodni muzej Slovenije 28, Ljubljana.

- Gabrovec, S. (2006): Stična II/1. Gomile starejše železne dobe/ Grabhügel aus der älteren Eisenzeit. Katalog, Siedlungsausgrabungen, Katalog, Catalogi et monographie, Narodni muzej Slovenije 36, Ljubljana.

- Gabrovec, S. and Svoljšak, D. (1983): Most na Soči (S. Lucia) I. Zgodovina raziskovanj in topografija/ Storia delle richerche e topografia, Catalogi et monographiae, Narodni muzej Slovenije 22, Ljubljana.

- Gabrovec, S. and Teržan, B. (2008): Stična II/2. Gomile starejše železne dobe/ Grabhügel aus der älteren Eisenzeit. Razprave/ Studien, Catalogi et monographiae, Narodni muzej Slovenije 38, Ljubljana.

- Guštin, M. (1973/1975): “Kronologija notranjske skupine/ Cronologia del gruppo preistorico della Notranjska (Carniola Interna)”, Arheološki vestnik, Ljubljana, 24, 461-506.

- Guštin, M. (1979): Notranjska. K začetkom železne dobe na Severnem Jadranu/ Zu den Anfängen der Eisenzeit an der nördlichen Adria, Catalogi et monographiae, Narodni muzej Slovenije 17, Ljubljana.

- Guštin, M., ed. (2012): Volčji grad, Komen.

- Guštin, M. and Teržan, B. (1977): “Beiträge zu den vorgeschichtlichen Beziehunggen zwischen dem Südostalpengebiet, dem nordwestlichen Balkan und dem südlichen Pannonien im 5. Jahrhundert”, in: Markotic, ed. 1977, 77-89.

- Guštin, M. and David, W., ed. (2014): The Clash of Cultures? The Celts and the Macedonian World, Schriften des Kelten-Römermuseums Manching 9, Manching.

- Gutjahr, C. and Tiefengraber, C., ed. (2015): Beiträge zur Hallstattzeit am Rande der Südostalpen, Akten des 2. Internationalen Symposiums am 10. und 11. Juni 2010 in Wildon (Steiermark/ Österreich), Internationale Archäologie. Arbeitsgemeinschaft, Symposium, Tagung, Kongress; 19 – Hengist-Studien 3, Rahden/ Westf.

- Hänsel, B., Mihovilić, K. and Teržan, B. (2015): Monkodonja 1. Istraživanje protourbanog naselja brončanog doba Istre. Knjiga 1 – Iskopavanje i nalazi građevina/ Monkodonja. Forschungen zu einer protourbanen Siedlung der Bronzezeit Istriens. Teil 1 – Die Grabung und der Baubefund, Monografije i katalozi, Arheološki muzej Istre 25, Pula.

- Haevernick T. E. (1981): “Hallstatt-Tassen. Jahrbuch RGZM 5, 1958, p. 8-17”, in: Haevernick 1981, 41-50.

- Haevernick, T. E. (1981): Beiträge zur Glasforschung. Die wichtigsten Aufsätze von 1938 bis 1981, Mainz.

- Haevernick, T. E. (1981): “Perlen mit zusammengesetzten Augen (‘compound-eye-beads’), Prähistorische Zeitschrift 47, 1972, p. 78-93”, in: Haevernick 1981, 233-244.

- Haevernick, T. E. (1981): “Zu den Glasperlen in Slowenien. Opuscula Iosepho Kastelic sexagenario dicata/ Festschrift Kastelic, Ljubljana, 1974, p. 61-65 (Situla, Narodni muzej Slovenije; 14-15)”, in: Haevernick 1981, 261-264.

- Haevernick, T. E. (1981): “Gesichtsperlen, Madrider Mitteilungen, 18, 1977, p. 152-231”, in: Haevernick 1981, 304-356.

- Hänsel, B. and Machnik, J., ed. (1998): Das Karpatenbecken und die Osteuropäische Steppe, Nomadenbewegungen und Kulturaustausch in den vorchristlichen Metallzeiten (4000-500 v.Chr), Südosteuropa-Schriften 20 / Prähistorische Archäologie in Südosteuropa 12, München – Rahden/Westf.

- Hencken, H. 1978): The Iron Age Cemetery of Magdalenska gora in Slovenia. Mecklenburg Collection, Part II, Bulletin American School of Prehistoric Research, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University 32, Cambridge, Mass.

- Jereb, M. (2016): Die Bronzefäße in Slowenien, Prähistorische Bronzefunde II / 19, Stuttgart.

- Jerem, E., Schönfelder, M. and Wieland, G., ed. (2010): Nord-Süd, Ost-West Kontakte während der Eisenzeit in Europa. Akten der Internationalen Tagungen der AG Eisenzeit in Hamburg und Sopron 2002, Archaeolingua 17, Budapest.

- Knez T. (1986): Novo mesto I. Halštatski grobovi/ Hallstattzeitliche Gräber, Carniola Archaeologica 1, Novo mesto.

- Krause, R. (2002): “Ein frühkeltischer Fürstensitz auf dem Ipf am Nördlinger Ries”, Antike Welt, Mainz, 33/ 5, 493-508.

- Kruh A. (2014): “42. Kobarid”, in: Teržan & Črešnar, ed. 2014, 615-626.

- Kunter, K. (1995): Glasperlen der vorrömischen Eisenzeit IV nach Unterlagen von Th. E. Haevernick (+). Schichtaugenperlen, Marburger Studien zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte 18, Espelkamp.

- Marchesetti, C. (1903) [1981]: I Castellieri preistorici di Trieste e della Regione Giulia, Trieste.

- Marchesetti, C. (1993): “Scavi nella necropoli di S. Lucia presso Tolmino (1885-1892), Bollettino della Società Adriatica di Scienze naturali in Trieste, 15, 1893, p. 95-490”, reprint: Marchesetti, C (1993): Scritti sulla necropoli di s. Lucia di Tolmino (Scavi 1884-1902), Trieste.

- Marchesetti, C. (1993): Scritti sulla necropoli di S. Lucia di Tolmino (Scavi 1884-1902), Trieste.

- Markotic, V., ed. (1977): Ancient Europe and the Mediterranean. Studies presented in honour of Hugh Hencken, Warminster.

- Mele, M. (2012): “Das Universalmuseum Joanneum und die Fürsten von Kleinklein (Großklein)”, Schild von Steier, Graz, 58, 42-61.

- Mlinar, M. (2002): Nove zanke svetolucijske uganke. Arheološke raziskave na Mostu na Soči: 2000 do 2001/ Sveta Lucija – New Stigma to the Enigma. Archaeological excavations at Most na Soči: 2000-2001, Tolmin.

- Mlinar M. and Gerbec T. (2011): Keltskih konj topòt- najdišče Bizjakova hiša v Kobaridu/ Hear the horses of Celts – the Bizjakova hiša site in Kobarid, Tolmin.

- Pabst, S. (2012): Die Brillenfibeln. Untersuchungen zu spätbronze- und ältereisenzeitlichen Frauentrachten zwischen Ostsee und Mittelmeer, Marburger Studien zur Vor- und Frühgeschichtre 25, Rahden/ Westf.

- Parzinger, H. (1988): Chronologie der Späthallstatt- und Frühlatène-Zeit. Studien zu Fundgruppen zwischen Mosel und Save, Acta humaniora – Quellen und Forschungen zur prähistorischen und provinzialrömischen Archäologie 4, Weinheim.

- Patek, E. (1993): Westungarn in der Hallstattzeit, Acta humaniora – Quellen und Forschungen zur prähistorischen und provinzialrömischen Archäologie 7, Weinheim.

- Peroni, R., ed. (1981): Necropoli e usi funerari nell´età del ferro, Archeologia: Materiali e problemi 5, Bari.

- Potrebica, H. (2013): Kneževi željeznog doba, Bibliotheca Historia Croatica 61, Zagreb.

- Slapšak, B. (1995): Možnosti študija poselitve v arheologiji. Arheo, Ljubljana, 17.

- Strmčnik, M. and Teržan, B. (2004): “O gomili halštatskega veljaka iz Pivole pod Poštelo/ On the Mound of the Hallstatt Dignitary from Pivola below Poštela”, Časopis za zgodovino in narodopisje/ Review for History and Ethnography, Maribor, 75 – n.v. 40/ 2-3, 217-238.

- Svoljšak, D. (1984): “Most na Soči (S. Lucia) e i suoi sistemi di difesa”, in: Preistoria del Caput Adriae. Atti del convegno internazionale, Trieste 19-20 novembre 1983, Udine, 115-118.

- Svoljšak D. (2001): “Zametki urbanizma v železnodobni naselbini na Mostu na Soči/ Zur Entstehung der Urbanisation in der eisenzeitlichen Siedlung von Most na Soči”, Arheološki vestnik, Ljubljana, 52, 131-138.

- Svoljšak, D. and Dular, J. (2016): Železnodobno naselje Most na Soči. Gradbeni izvidi in najdbe/ The Iron Age Settlement at Most na Soči. Setllement structures and small finds, Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 33, Ljubljana.

- Svoljšak, D. and Pogačnik, A. (2001): Tolmin, prazgodovinsko grobišče I – Katalog/ Tolmin, the prehistoric cemetery I – Catalogue, Catalogi et monographiae, Narodni muzej Slovenije 34, Ljubljana.

- Svoljšak, D. and Pogačnik, A. (2002): Tolmin, prazgodovinsko grobišče II – Razprave/ Tolmin, the prehistoric cemetery II – Treatises, Catalogi et monographiae, Narodni muzej Slovenije 35, Ljubljana.

- Šimek, M. (1998): “Ein Grabhügel mit Pferdebestattung bei Jalžabet, Kroatien”, in: Hänsel & Machnik, ed. 1998, 493-510.

- Šimek, M. (2004): “Grupa Martijanec-Kaptol/ Martijanec-Kaptol Group/ Martijanec-Kaptol-Gruppe”, in: Ratnici na razmeđu istoka i zapada. Starije željezno doba u kontinentalnoj Hrvatskoj/ Warriors at the Crossroads of East and West/ Krieger am Scheideweg zwischen Ost und West, Zagreb, 79-129.

- Tecco Hvala, S. (2012): Magdalenska gora. Družbena struktura in grobni rituali železnodobne skupnosti/ Social structure and burial rites of the Iron Age community, Opera Institutu Archaeologici Sloveniae 26, Ljubljana.

- Tecco Hvala, S., Dular, J. and Kocuvan, E. (2004): Železnodobne gomile na Magdalenski gori/ Eisenzeitliche Grabhügel auf der Magdalenska gora, Catalogi et monographiae, Narodni muzej Slovenije 36, Ljubljana.

- Teržan, B. (1985): Poskus rekonstrukcije halštatske družbene strukture v dolenjskem kulturnem krogu/ Ein Rekonstruktionsversuch der Gesellschaftsstruktur im Dolenjsko-Kreis der Hallstattkultur. Arheološki vestnik, Ljubljana, 36, 1985, p. 77-105.

- Teržan, B. (1990): Starejša železna doba na Slovenskem Štajerskem/ The Early Iron Age in Slovenian Styria, Catalogi et monographiae, Narodni muzej Slovenije 25, Ljubljana.

- Teržan, B. (1997): “Heros der Hallstattzeit. Beobachtungen zum Status an Gräbern um das Caput Adriae”, in: Becker et al., ed. 1997, 653-669.

- Teržan, B. (1998): “Auswirkungen des skythisch geprägten Kulturkreises auf die hallstattzeitlichen Kulturgruppen Pannoniens und des Ostalpenraumes”, in: Hänsel & Machnik, ed. 1998, 511-560.

- Teržan, B. (2001): “Richterin und Kriegsgöttin in der Hallstattzeit. Versuch einer Interpretation”, Praehistorische Zeitschrift, Berlin-New York, 76/1, 74-86.

- Teržan, B. (2008): “Stiške skice/ Stična-Skizzen”, in: Gabrovec & Teržan, ed. 2008, 189-325.

- Teržan, B. (2009): “Eine latèneartige Fremdform im hallstättischen Vače”, in: Tiefengraber et al., ed. 2009, 85-99.

- Teržan, B. (2011a): “Horses and cauldrons: Some remarks on horse and chariot races in situla art”, in: Casini, ed. 2011, 303-325.

- Teržan, B. (2011b): “Hallstatt Europe: Some aspects of religion and social structure”, in: Tsetskhladze, ed. 2011, 233-264.

- Teržan, B. (2014a): “Early La Tène elements in the late south eastern Alpine Hallstatt culture – an outline”, in: Guštin & David, ed. 2014, 19-29.

- Teržan, B. (2014b): “O konjskih dirkah sredi 1. tisočletja pr. Kr.: konj in kotel v situlski umetnosti”, in: Varia. Dissertationes 28, Academia scientiarum et artium Slovenica, Cl. 1: Historia et sociologia, Ljubljana.

- Teržan, B. (2015): “Zgodnjelatenske prvine v poznem obdobju halštatske kulture na območju Slovenije – kazalci »diplomatskih stikov » v 5. in 4. stol. pr. Kr.?”, in: Zbornik ob stoletnici akad. Antona Vratuše/ Antonio Vratuša centenario, Dissertationes 31, Academia scientiarum et artium Slovenica,, Cl. 1: Historia et sociologia 31, Ljubljana.

- Teržan, B. and Črešnar, M. (2014): “Poskus absolutnega datiranja starejše železne dobe na Slovenskem/ Attempt at an absolute dating of the Early Iron age in Slovenia”, in: Teržan & Črešnar, ed. 2014, 703-725.

- Teržan, B. and Črešnar, M., ed. (2014): Absolutno datiranje bronaste in železne dobe na Slovenskem/ Absolute Dating of the Bronze and Iron Ages in Slovenia, Catalogi et monographiae, Narodni muzej Slovenije 40, Ljubljana.

- Teržan, B. and Trampuž, N. (1973-1975): “Prispevek h kronologiji svetolucijske skupine/ Contributto alla cronologia del gruppo preistorico di Santa Lucia”, Arheološki vestnik, Ljubljana, 416-460.

- Teržan, B., Lo Schiavo, F. and Trampuž-Orel, N. (1984-1985): Most na Soči (S. Lucia) II, Catalogi et monographiae, Narodni muzej Slovenije 23/ 1 – 23/ 2, Ljubljana.

- Teržan, B., Črešnar, M. and Mušič, B. (2015): “Early Iron Age barrows in the eyes of complementary archaeological research. Case study of Poštela near Maribor (Podravje, Slovenia)”, in: Gutjahr & Tiefengraber, ed. 2015, 61-82.

- Teržan, B. and Turk, P. (2005): “The Iron Age tower upon Ostri vrh”, in: Bandelli & Montagnari Kokelj, ed. 2005, 339-352.

- Teržan, B. and Turk, P. (2014): “40. Ostri vrh pri Štanjelu”, in: Teržan & Črešnar, ed. 2014, 603-610.

- Tiefengeaber, G., Tiefengraber, S. and Moser, S. (2013): Reiterkrieger? Priesterin? Das Rätsel des Kultwagengrabes von Strettweg bei Judenburg, Judenburg.

- Tiefengraber, G., Kavur, B. and Gaspari, A., ed. (2009): Keltske študije II/ Studies in Celtic Archaeology. Papers in honour of Mitja Guštin, Protohistoire européenne 11, Montagnac.

- Tsetskhladze G.R., ed. (2011): The Black Sea, Greece, Anatolia and Europe in the First Millenium BC, Journal Ancient West Suppl. Colloquia Antiqua & East 1, Leuven-Paris-Walpole, MA.

- Turk, P. (2010): “Po gradiščih vzdolž severnega kraškega roba”, Kras, Sveto, 99-100, 28-31.

- Turk, P. and Jereb, M. (2006): “Poselitev Braniške doline v prazgodovini in rimskem obdobju – arheološka pričevanja”, Kronika Rihemberka – Branika II, Branik, 9-18.

- Vinski Gasparini, K. (1987): “Grupa Martijanec-Kaptol”, in: Praistorija jugoslavenskih zemalja V. Željezno doba, Sarajevo, 182-231.

- Vitri S. (1980): “Un´oinochoe etrusca da S. Lucia di Tolmino – Most na Soči”, in: Zbornik posvečen Stanetu Gabrovcu ob šestdesetletnici. Situla 20/21, Ljubljana, 267-277.

- Wells, P.S. (1981): The Emergency of an Iron Age Economy. The Mecklenburg grave groups from Hallstatt and Stična. Mecklenburg Collection, Part III, Bulletin. American School of Prehistoric Research, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University 33, Cambridge, Mass.

- Žbona-Trkman, B. and Svoljšak, D. (1981): Most na Soči 1880-1980 – Sto let arheoloških raziskovanj, Tolmin, maj-julij 1981, Nova Gorica.